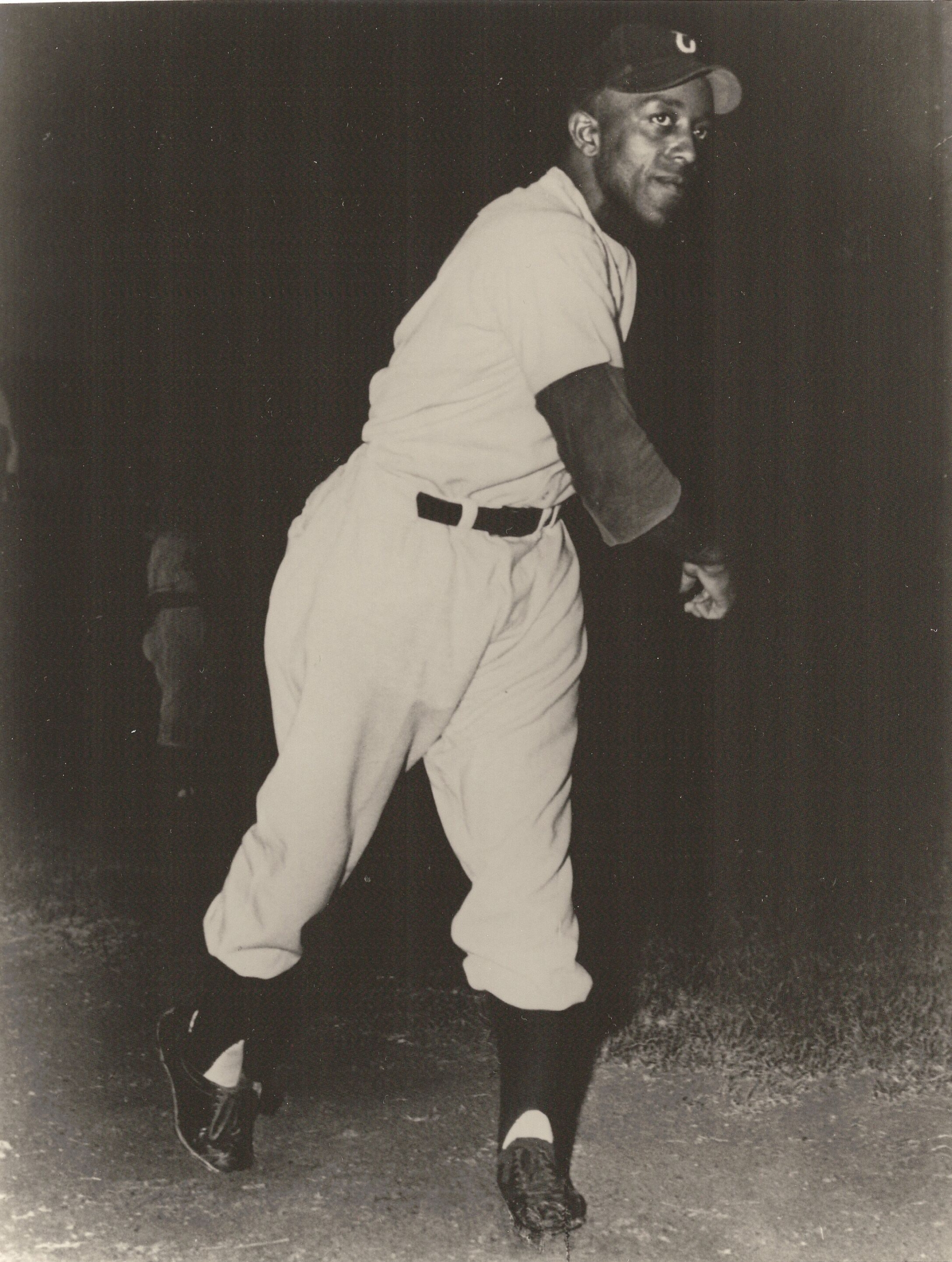

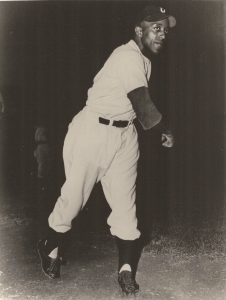

May 5, 1946: Leon Day throws Opening Day no-hitter for Newark Eagles

It is common knowledge that Cleveland Indians Hall of Famer Bob Feller tossed the only Opening Day no-hitter in major-league history against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park on April 16, 1940. On the 75th anniversary of the event, Major League Baseball’s official website touted it as “the first — and to this day — the only Opening Day no-hitter in modern baseball history.”1

It is common knowledge that Cleveland Indians Hall of Famer Bob Feller tossed the only Opening Day no-hitter in major-league history against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park on April 16, 1940. On the 75th anniversary of the event, Major League Baseball’s official website touted it as “the first — and to this day — the only Opening Day no-hitter in modern baseball history.”1

The fact that Rapid Robert accomplished the feat first is not in dispute, but the assertion that he is the only pitcher to do so is entirely in error. Six years after Feller’s accomplishment, Newark Eagles right-hander Leon Day no-hit the Philadelphia Stars on May 5, 1946, which was Opening Day for the Negro National League.

Feller’s no-hitter did not lack for thrills as he had to protect a 1-0 lead in the ninth inning. Chicago’s Luke Appling, batting with two outs, fouled off several pitches, so Feller decided to walk him in order to face the next batter in the White Sox lineup. The strategy almost backfired when Taft Wright smacked a hard grounder that “necessitated a diving play by second baseman Ray Mack, who knocked it down, whirled and made a perfect throw” to end the game.2

In spite of the thrilling conclusion to Feller’s gem, Day’s no-hitter was so filled with excitement that it made Feller’s game seem almost mundane. The fact that Newark’s tilt with Philadelphia ended with a close 2-0 score actually turned out to be only half of the action in this contest. Though it was a shining moment for Day on the mound, a near-riot in the sixth inning — precipitated by a controversial call at home plate — and the concern about the impact that the event might have on the progress of baseball’s integration received equal attention. In light of the attention the game received at the time, one might think the game would be well-remembered, but like much of Negro Leagues history it fell into obscurity for many baseball aficionados.

The 1946 opener between the Eagles and the Stars at Newark’s Ruppert Stadium was a highly anticipated event. The Wilmington Morning News previewed Newark’s season by reporting that Eagles manager Raleigh “Biz” Mackey “has whipped a host of ex-GIs into shape for the coming race and feels certain that the Newark club will be in the thick of the pennant battle.”3 Day was one of those ex-GIs, a group that included Larry Doby, Oscar Givens, Monte Irvin, Clarence “Pint” Isreal, Max Manning, Charles Parks, and Leon Ruffin. The Army had drafted Day on September 1, 1943, and he had served in the 818th Amphibian Battalion — with which he had landed at Utah Beach on D-Day — before being discharged in February 1946.4 The big question surrounding Day now was whether he could resume his stellar pitching career where he had left off prior to his military service.

In addition to the Eagles’ high hopes for their pennant chances and Day’s return to the mound, the Newark Star-Ledger noted:

“A crowd of about 15,000 is expected to watch the two National Negro League combinations launch the season. The usual pre-game ceremonies and parade will attend the occasion. Mayor Vincent J. Murphy has proclaimed today as “Newark Eagles” Day by proclamation issued earlier this week.”5

Effa Manley, who co-owned the Eagles with her husband, Abe, often solicited funds for various organizations during the team’s home games, and she had volunteers out in force to collect donations for the NAACP on this occasion.6 Before the start of the action, Deputy Mayor Barney Koplin tossed out the first pitch.7 Thus, although the crowd of 8,514 constituted little more than half the anticipated throng, the day was still a hallmark occasion.

Once the game began, the fans in attendance were not disappointed. Day admitted, “I was a little nervous, like I always was at the beginning of a game, but after I got started, everything was all right.”8 He overcame his jitters and pitched every bit as well as he had in his last all-star season of 1942. The Baltimore Afro-American enthused, “[T]he crack Bird flinger virtually handcuffed the opposition.”9 However, Day was locked in a mound duel with Philadelphia southpaw Barney Brown, who matched him zero-for-zero on the scoreboard through the first five innings.

Although Day was pitching brilliantly, the umpires and official scorer did make some questionable calls in the game. Bill “Ready” Cash, the Stars’ catcher, years later went so far as to declare about home-plate umpire Peter Strauch, “I knew he was really screwing us during the game. Nobody can tell me that Eagles owner Effa Manley didn’t offer him a little something extra to cheat us.”10 Though Cash is the only player to have engaged in a conspiracy theory about the umpiring, the game was contentious enough that the Trenton Evening Times noted it “was almost called several times due to arguments with the umpires.”11 As for the scorer’s calls, Newark shortstop Benny Felder was charged with two errors, one of which was controversial. On the questionable play, Felder fielded a grounder cleanly but hesitated on his throw and then unleashed a wild one to first as he tried to nail the runner in time. Cash was irked that the play was scored as an error, and even Day graciously conceded, “(Felder) should have had him out, but they probably should have given the man a hit.”12

Day’s no-hit bid provided the excitement through the top of the sixth inning, but the poor play-calling took center stage in the bottom of the same frame as Newark broke through with the only runs of the game. Isreal led off with a line-drive triple to right-center field and scored the first run on Doby’s single up the middle. Doby stole second base and then, after Irvin flied out, the most notorious play of the game occurred. Lennie Pearson hit a slow dribbler to Philly second baseman Mahlon Duckett, who threw to first baseman Wesley “Doc” Dennis for the out.13 In the meantime, Doby was attempting to score on the play. Cash remarked in his autobiography, “I mean, what was he thinking? Most players with good sense would’ve held at third. But Doby wasn’t most players.”14

As Doby steamed around third base, Cash received the relay throw from Dennis. Doby slid into home plate head first as Cash stretched forward and applied the tag. Although it appeared to most observers that Doby was clearly out on the play — a photo in the New York Amsterdam News’s May 11 edition later confirmed as much — Strauch called him safe.15 In the heat of the moment, Cash jumped up to dispute the call, wildly waving his arms around, and ended up hitting Strauch with his glove hand and knocking him to the ground.

Accounts of Cash’s exact action, as well as speculation as to whether or not he intended to hit Strauch, vary. The Afro-American wrote that Cash “jumped Struack [sic], nailing him to the ground.”16 Similarly, the Amsterdam News reported that Cash “hit the umpire in the left eye.”17 Cash asserted that he had accidentally hit Strauch “under his chin, knocking him to the ground,” and was adamant that he had not attacked the umpire.18 Irvin later provided the most germane observation, writing, “[R]egardless of whether it was intentional or not, the ump went down.”19

Homer “Goose” Curry, Philadelphia’s player-manager, escalated the situation when he ran from his position in right field and delivered a few kicks to Strauch as he was down. The fact that Strauch was a white man turned this baseball fracas into a potential race riot as there were also white fans in attendance. Both benches emptied as players tried to separate Cash and Curry from Strauch. Fans also spilled onto the field, and a general melee ensued. The police were called in, and it took mounted officers and foot patrolmen 30 minutes to restore order in the ballpark.

Before play resumed, Cash was ejected and was replaced at catcher by Pete Jones. Curry also was expelled, but he refused to go quietly. The Amsterdam News tried to inject some humor into its account of the action, stating that “‘Goose’ refused to vamoose after Ump Strauch had pulled the watch on him, but the Law took matters in their hand and out went the ‘Goose.’”20 After Curry had been removed, he was replaced in right field by Harry “Suitcase” Simpson.

The Stars continued the game under protest, but later withdrew their complaint because Isreal’s run, which provided the winning margin, was not contested. Irvin was struck by something other than the on-field fisticuffs, as he noted, “I guess the most interesting thing about that incident was that Leon Day just sat calmly in the dugout watching the whole thing until it was over. Then he went back out and finished his no-hitter.”21

Day put an exclamation point on his effort by striking out Henry McHenry, who was pinch-hitting for Brown, on “three lightning-sharp pitches” to end the game.22 He recalled that before he faced McHenry, one of his teammates told him, “Don’t throw him anything but fastballs, he’s a slow swinger.”23 Day heeded the advice, saying, “Every pitch I raised it a little. The last one was up around his eyes.”24

A final round of chaos ensued when some fans decided to celebrate the announcement of Day’s feat by throwing seat cushions into the crowds that were heading for the stadium exits. Just as umpire Strauch had been struck during the in-game insurrection, a woman was hit by one of these flying projectiles in the post-game pandemonium and was knocked off her feet. The Newark News reported, “She was knocked unconscious after her head struck the concrete floor of the grandstand, but was revived without medical attention.”25

The action of certain overzealous fans notwithstanding, there was ample reason to celebrate Day’s accomplishment. He had faced only 29 batters, striking out six and allowing three baserunners on a walk and the two errors by Felder; none of the baserunners reached second base. Effa Manley extolled her starting pitcher’s heroics in a letter to an acquaintance, relating the fact that the no-hitter had ended when McHenry “[w]ent down swinging” and exclaiming, “Can you imagine what a thrill that was?”26 However, she was also concerned about the on-field incident with Strauch, especially since controversies with umpires had become quite frequent in the Negro Leagues. In 1946 all eyes were not only on Jackie Robinson, who had just begun his first and only season in the minor leagues with the Montreal Royals, but also on the Negro Leagues’ players. In particular, some members of the African-American press were concerned that any perceived misbehavior on the part of black ballplayers would bring black baseball into disrepute and would affect how Organized Baseball chose to deal with the Negro Leagues or, worse yet, that it might stall or quash the game’s integration altogether.27

In an effort to prevent future flare-ups, Effa Manley wrote to Ed Gottlieb, the white promoter who assigned the umpires for Eagles games at Ruppert Stadium, and questioned whether Strauch should continue to work games for the team.28 She expressed concern that “[t]he Negro men are as prejudiced against the white umpires as the white people are against the colored.”29 Manley’s request to keep Strauch out of future Newark games, and thus to keep the races separate, was consistent with her long-held desire that Negro League baseball should be exclusively in the hands of African-Americans. Effa objected to white ownership of some of the NNL clubs, and she and Abe had fought losing battles to try to wrest away control of nonleague games, which were essential to the team’s financial survival, from powerful white promoters like Gottlieb. However, in spite of her separatist outlook on black baseball, she did not stand in any player’s way when a major-league team offered an opportunity, though she did fight to receive compensation from the teams that signed the Eagles players.

On May 13 the NNL office handed Cash a three-game suspension and levied a $50 fine while also announcing, “In the future any player striking an umpire will be fined $100 and will be suspended for ten days.”30 Oddly, Curry incurred no punishment for his actions even though they clearly had been deliberate and he had been forced from the field by the police. He may have escaped further repercussions because “[b]laming his conduct on the excitement of the game, Curry after the game apologized to Struack [sic] for himself and Cash.”31 In contrast to his manager, Cash remained unapologetic, asserting decades later, “And to this day, some people think the reason I didn’t make it to the majors was because I smacked a white umpire. Shoot, as bad as that call was, I should’ve stomped him.”32

As for Day, he began his comeback campaign with a flourish, but he also injured his arm during the game when he fielded a bunt and slipped while trying to throw to first for the out. According to Day, “When I threw it, I could feel something pull. … That was opening day and I never was no good the whole season.”33 He nevertheless finished the 1946 NNL season with a 14-4 record, a 2.53 ERA, and a league-leading 65 strikeouts in 174 innings pitched.34 His injury did worsen as the season progressed, though, and he was less effective in the two games he pitched against the Kansas City Monarchs in the World Series. He still was a major contributor to Newark’s championship as he made a sparkling, game-saving catch in Game Six after he had moved from the mound, where he had started the game, to the outfield.

Leon Day was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame on March 7, 1995, just six days before he died of heart failure in Baltimore at the age of 78. Four other members of the 1946 Newark Eagles keep company with him in Cooperstown, New York — Doby, Irvin, Mackey, and Effa Manley — demonstrating that both the team and its feats, including Day’s Opening Day no-hitter, are as worthy of commemoration as Feller and his accomplishments.

Notes

1 Alyson Footer, “#TBT: Feller Tosses the One and Only Opening Day No-Hitter,” mlb.com/news/tbt-bob-feller-tosses-the-one-and-only-opening-day-no-hitter/c-118626392, accessed January 24, 2018.

2 Ibid.

3 “Newark Eagles to Meet Stars,” Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), May 6, 1946: 15.

4 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball in Wartime: Leon Day,” baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/day_leon.htm, accessed January 24, 2018.

5 “Eagles Make Bow Today,” Newark Star-Ledger, May 5, 1946: 27.

6 James Overmyer, Queen of the Negro Leagues: Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1998), 59.

7 “No-Hit Bow: Day, Eagles Ace, Throttles Stars 2-0 in Opener,” Newark Star-Ledger, May 6, 1946: 11.

8 James A. Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons: Essays on Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012), 154-55.

9 “Day Hurls No-Hitter as Eagles Cop Opener, 2-0,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 11, 1946: 29.

10 Bill “Ready” Cash and Al Hunter Jr., Thou Shalt Not Steal: The Baseball Life and Times of a Rifle-Armed Negro League Catcher (Philadelphia: Love Eagle Books, 2012), 73.

11 “Eagles, Stars Clash Tonight,” Trenton Evening Times, May 8, 1946: 25.

12 James A. Riley, Dandy, Day, and the Devil (Cocoa, Florida: TK Publishers, 1987), 69.

13 Cash remembered the play somewhat differently in his autobiography, which was written more than 60 years after the game in question. He claimed that Irvin had hit the slow grounder to Stars shortstop Frank Austin rather than Pearson hitting it to the second baseman, Duckett. An examination of the box score shows that Cash’s memory was faulty after the long interval, his protestations to the contrary notwithstanding. Cash remembered correctly that Isreal tripled, Doby singled, and that there then was a fly out before the grounder on which Doby tried to score. An examination of the game’s box score shows that Irvin batted between Doby and Pearson in Newark’s lineup that day; thus, he had to have been the batter who flied out, and Pearson had to have been the batter who hit the grounder. Additionally, Pearson must have hit the ball to Duckett, as was reported at the time; if the ball had been hit to Austin at short, it is doubtful that Doby would have tried to advance even to third base, let alone to attempt to score on the play. (For Cash’s account, see Cash, 75).

14 Cash and Hunter, 5.

15 “Play That Caused Near Riot in Newark Eagle’s No Hit Win From Philly,” New York Amsterdam News, May 11, 1946: 12.

16 “Day Hurls No-Hitter as Eagles Cop Opener, 2-0.”

17 “Play That Caused Near Riot in Newark Eagle’s No Hit Win From Philly.”

18 Cash and Hunter, 6, 74-75.

19 Monte Irvin with James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First: The Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1996), 74.

20 “Police Halt Philadelphia Stars-Newark Eagles Riot,” New York Amsterdam News, May 11, 1946: 1.

21 Irvin with Riley, 74.

22 “Play That Caused Near Riot in Newark Eagle’s No Hit Win From Philly.”

23 Riley, Dandy, Day, and the Devil, 70.

24 Ibid.

25 Jim Ryall, “Fireworks at Eagles Game/Fists Fly as Leon Day Hurls No-Hitter,” Newark News, May 6, 1946.

26 Bob Luke, The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 124.

27 Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Wendell Smith took Newark and both the NNL and NAL league offices to task after the Eagles walked out on a July 21, 1946, exhibition game against the NAL’s Cleveland Buckeyes because a controversial call went against them. When it became apparent that neither league office intended to penalize Newark, Smith wrote a scathing column in which he admonished:

“This attitude simply substantiates Branch Rickey’s charge that ‘Negro leagues do not actually exist.’ When the presidents of the two leagues refuse to step in and crack down on teams that take the baseball law into their own hands, it simply means that the rules and regulations governing the game mean absolutely nothing.

Consequently, the fans never can be sure that they’re going to get what they pay for. …” (See Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat: What Happens When a Team Quits?” Pittsburgh Courier, August 3, 1946: 16.)

Upon reading Smith’s article, Effa Manley responded with a letter in which she attempted to explain why manager Biz Mackey had led the Eagles off the field without completing the game. She concluded her missive to Smith, which was printed in his next column, by asserting, “I will never condone any unsportsmanlike conduct from the Eagles. On the other hand, I do not expect them to accept decisions like this one without protesting.” (See Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat: Mrs. Manley Has Her Say,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 10, 1946: 16.)

Manley’s justifications for her team’s actions notwithstanding, Smith’s column reflected the concerns of most observers who wanted to ensure that Negro League players did not behave in a manner that would give Organized Baseball’s leagues a convenient excuse to discontinue the integration of the game.

28 Luke, 124. Ed Gottlieb, in addition to being one of the prominent white promoters of black baseball games, was also a part-owner of the Philadelphia Stars. In light of this fact, Cash’s accusation that Effa Manley had paid off Strauch to call the opener in Newark’s favor has little credence, if it ever had any at all. Strauch stood to lose more money by showing bias against the Stars and displeasing Gottlieb, who had the power not to assign him to work future games, than he had to gain by accepting a one-time bribe from Manley.

29 Ibid.

30 “8 Players Get 5-Year Suspensions, Elites Lose Star to Grays in NNL Action at Philly,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 18, 1946: 30. In his autobiography, Cash gives the fine as $25 (See Cash, 6 and 76), but the contemporary newspaper account reported a $50 fine.

31 “Day Hurls No-Hitter as Eagles Cop Opener, 2-0.”

32 Cash and Hunter, 6.

33 Riley, Dandy, Day, and the Devil, 70.

34 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 436. It should be noted that — as is often the case with Negro League ballplayers — different sources list different statistics for Day in 1946. Often the discrepancy results from the fact that one source includes both league and exhibition games while another source includes only league statistics. In other instances, more recent research that has been able to make use of newly available source material, such as digitized newspaper archives, may have turned up additional games that have been added to the statistical record.

Additional Stats

Newark Eagles 2

Philadelphia Stars 0

Ruppert Stadium

Newark, NJ

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.