October 2, 1949: Yankees come out on top in winner-take-all contest

At the end of the 1948 season, the New York Yankees fired their manager, Bucky Harris. The team had just completed what was for them a subpar year, finishing in third place behind the Boston Red Sox and Cleveland Indians. Harris was not without credentials, having guided the Yankees to the 1947 World Series championship, his second ring as a manager. A look at the 1948 team revealed a veteran squad, with five primary position-player starters 30 years old and over, as were two of the top three winning pitchers.

At the end of the 1948 season, the New York Yankees fired their manager, Bucky Harris. The team had just completed what was for them a subpar year, finishing in third place behind the Boston Red Sox and Cleveland Indians. Harris was not without credentials, having guided the Yankees to the 1947 World Series championship, his second ring as a manager. A look at the 1948 team revealed a veteran squad, with five primary position-player starters 30 years old and over, as were two of the top three winning pitchers.

An influx of youth and energy was in order, but general manager George Weiss hired a 58-year old former National League manager with a lifetime losing record to replace Harris. Casey Stengel had managed in the major leagues for almost nine seasons with an undistinguished 581-742 record – his best finish a 77-75 showing and a fifth-place finish with the Boston Bees in 1938. He was not yet Casey Stengel, Hall of Fame manager. He was an old, undistinguished skipper, widely considered a clown for his antics as a player and a gift for the gab in his managerial career.

The baseball world howled, with predictions of doomsday for the New Yorkers. In Baseball Digest, Chicago sportswriter John Carmichael predicted another third-place finish for Stengel’s crew.1 This forecast was charitable in comparison to that of The Sporting News, which anticipated the team finishing in fourth place.2

Clearly, Stengel had something to prove.

Casey was a prodigy of John McGraw, but his reverence and lessons learned hadn’t provided the results he craved. Behind the “Stengelese” – the goofiness – there was a fierce competitor.

The image of Stengel and the notoriously corporate Yankees didn’t seem to align. Stengel himself in his initial press conference seemed to recognize this, stating, “This is a 5 million dollar business. They don’t hand out jobs like this because you’re a friend.”3

Stengel and Weiss oversaw an overhauling of the roster, with all but one position during the season primarily manned by someone different than in the 94-win 1948 version. Injuries were a big part of the equation: Due to aches and pains the heart of the batting order – Tommy Henrich, Joe DiMaggio, and Yogi Berra – was in the same lineup only 17 games all year. The Sporting News chronicled at least 71 injuries suffered by Yankee players.4 No doubt the most devastating was the bad heel that sidelined center fielder Joe DiMaggio all season until June 28.

Despite the uphill climb, Stengel deftly steered the Yanks to a 41-24 start prior to DiMaggio’s return. The team held first place from Opening Day through September 26, when it was passed in the standings by the Red Sox, who were managed by longtime Yankees skipper Joe McCarthy and had come back from a 12-game deficit on July 4. Over the week after September 26, the teams stayed within a game of each other, setting up the final two-game confrontation of October 1 and 2 at Yankee Stadium. Boston came into the set leading by a game and needing only one win to clinch the American League pennant. They seemed on their way to the flag on October 1, when they jumped out to an early 4-0 lead. An improbable Yankees comeback ended up taking that first game, moving the teams into a tie for the final contest.

On the morning of October 2, 1949, the Yankees and Red Sox had identical 96-57 records. This day’s game would decide who represented the American League in the World Series against either the St. Louis Cardinals or Brooklyn Dodgers, who were separated by just one game in the race for the National League flag. It was a baseball fan’s dream; both pennant races were coming down to the last day of the season, only the second time in baseball history (after 1908) that this had happened.5

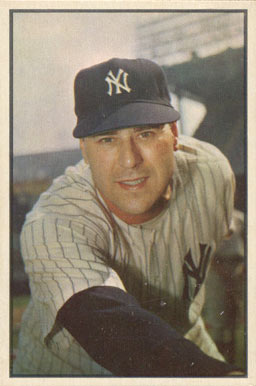

For the biggest game of his managerial career, Stengel handed the ball to ace right-hander Vic Raschi, who came into the contest with a 20-10 record and a 3.35 ERA. Boston sent out Ellis Kinder, a previously undistinguished 34-year-old right-hander finishing up the season of his life, 23-5 and 3.45. Kinder had been 4-0 against the Yankees in 1949.

Against the backdrop of a jam-packed crowd of 68,055 in Yankee Stadium, the hometown team jumped onto the scoreboard right away. Phil Rizzuto led off the bottom of the first with a triple down the left-field line and was driven in on Henrich’s groundout to second.

Raschi and Kinder then settled into a classic pitchers’ duel, both hurlers putting zeros on the scoreboard for the next six innings. In the top of the eighth, Kinder’s spot in the batting order came up, but with his team behind, Boston manager McCarthy went to the bench in search of a spark. He sent up Tom Wright, fresh off a .368 season in Triple-A Louisville, to hit for his pitcher. Wright came through, drawing a walk, but was wiped out when Dom DiMaggio grounded into a double play.

In the bottom of the frame, McCarthy sent to the mound his other ace pitcher, Mel Parnell, the 25-game-winning All-Star left-hander who later finished fourth in the American League MVP voting. Henrich greeted Parnell with a solo home run and Berra singled. McCarthy didn’t waste any time, going again to the bullpen, this time for Tex Hughson, an ace of the 1946 pennant-winning Red Sox. Hughson induced a double-play grounder by Joe DiMaggio, and the threat seemed to be over. Alas, things were just beginning, as two singles and a walk brought Jerry Coleman to the plate with the bases loaded. The Yankees second sacker, who later went on to finish third in Rookie of the Year balloting, lifted a short fly to right field which barely escaped the grasp of the diving right-fielder Al Zarilla.6 The bases cleared, and though Coleman was thrown out going for a triple, the Yankees suddenly had a 5-0 lead and with the dominant Raschi going for the shutout. Things looked good for the hometown team.

It wouldn’t be easy, though, as the Red Sox had their heavy hitters due up.

Raschi retired Johnny Pesky on a fly ball to center field, then walked Ted Williams and allowed him to advance to second on a wild pitch. Vern Stephens singled him to third. Bobby Doerr’s triple past Joe DiMaggio cut the lead to 5-2, and the game was starting to get more interesting. At this point, DiMaggio took himself out, exhausted. Cliff Mapes slid from right field to center.

Al Zarilla then flied out to Mapes in shallow center, with Doerr holding third. Billy Goodman singled him in, and it was 5-3, with the tying run coming to the plate in catcher Birdie Tebbetts. Henrich and Berra walked toward the mound to give Raschi some encouragement. Raschi, an intense, angry man while on the mound, would have none of that.

“Give me the goddamn ball and get the hell out of here.”7

Both players immediately returned to their positions. Raschi induced Tebbetts to foul out to Henrich. The Yankees were the 1949 American League champions.

Boston fans, who had endured a final-game defeat in 1948, were devastated and questioned the removal of Kinder, though many pundits, including Harold Kaese of the Boston Globe, gave McCarthy the benefit of the doubt: “To leave Kinder in was playing for what? For a 1-0 defeat.8

For Ted Williams, the loss was doubly frustrating, as on top of the pennant race disappointment, his hitless performance allowed Detroit’s George Kell to overtake him for the AL batting crown by the slimmest of margins – .3429 to .3427.

Word came afterward of Brooklyn’s win over Philadelphia to sew up the NL flag. For the eighth time – the third with the Dodgers –the Yankees would engage in a Subway Series.

Stengel was humble in victory: “I didn’t catch a fly ball, make a base hit, or strike out a guy all season. So why should I take any credit.”9 To his players went the ultimate praise: “I want to thank all these players for giving me the greatest thrill of my life.”10

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA194910020.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1949/B10020NYA1949.htm

Notes

1 In the April 1949 Issue of Baseball Digest, Carmichael wrote, “This Yankee team may be on the verge of bending, if not entirely breaking, under the slender thread of too little in the way of top-flight players.” 5-6.

2 “Pennants Expected to Fly from New Poles,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1949: 3.

3 Robert Creamer, Stengel, His Life and Times (New York: Fireside, 1984), 212.

4 “Chart on Yankee Hospital List,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1949: 10.

5 On the final days of their season in 1908, the Chicago Cubs beat the New York Giants for the National League pennant. Two days earlier, the Detroit Tigers beat the Chicago White Sox for the AL pennant. The Cubs won the World Series in five games.

6 “Yanks Whip Red Sox in Season Finale to Win Sixteenth American League Pennant,” The New York Times, October 3, 1949:21.

7 Peter Golenbock, Dynasty: The New York Yankees 1949-64 (New York: Berkley, 2000), 42.

8 Harold Kaese, “McCarthy’s Lifting of Kinder in 8th Called Good Baseball,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1949: 18.

9 “Stengel an Elder Statesman Now,” Baseball Digest, November 1949: 19.

10 Creamer, Stengel, His Life and Times, 233.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 5

Boston Red Sox 3

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.