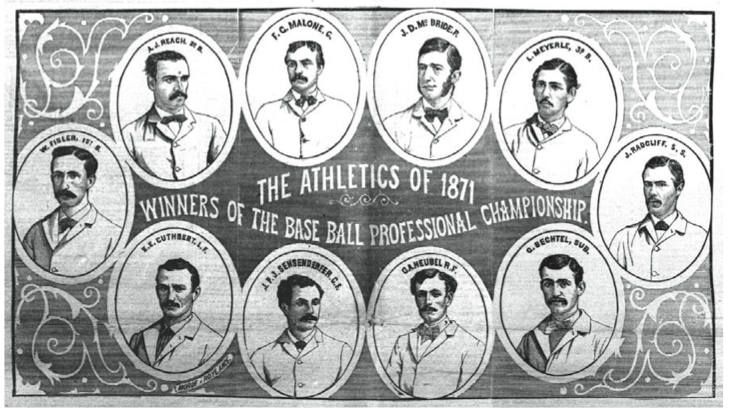

October 30, 1871: Berkenstock returns after 4-year absence to help Philadelphia win first league championship

Major League Baseball dates its inception to 1876, but nearly all of the men who played in the newly formed National League had played in its predecessor circuit, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Clubs, which operated from 1871 through 1875. The 1871 pennant race went down to the final day amid improbable and poignant circumstances that will never be equaled.

Major League Baseball dates its inception to 1876, but nearly all of the men who played in the newly formed National League had played in its predecessor circuit, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Clubs, which operated from 1871 through 1875. The 1871 pennant race went down to the final day amid improbable and poignant circumstances that will never be equaled.

When the National Association was founded on March 17, 1871, it was ruled that each club would play five games with the other eight and the winner of three games will have won that “championship series.” This was a term designed to separate league contests from the many exhibition games that each club played along the way. The “whip pennant” would be awarded to the team winning the most series against the other league teams, not the most games won (the rule until 1883) or the top winning percentage (ever since). The term “whip pennant” was synonymous with the term for a flag on the masthead of a ship. Over the years, it has evolved into the term pennant.

Of the clubs that entered the new league, three battled for the pennant from the outset: Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia. Harry Wright’s Boston Red Stockings took their name as well as several key players — including his brother George Wright, the game’s greatest star — from his famous Cincinnati nine, undefeated in 1869 yet disbanded only a year later. Chicago had built its White Stockings club on the Cincinnati model, luring talented players from other clubs with rich offers. The White Stockings are the direct ancestor of today’s Chicago Cubs.

Chicago’s White Stockings built a new ballpark at Randolph and Michigan on the lakefront. On April 29, 1871, the New York Clipper opined, “They will have accommodations on the grounds to seat 6,500 people, and standing room for plenty more. With the single exception of its being somewhat narrow, they will have one of the finest ball parks in the country.”1 Philadelphia’s venerable Athletic Base Ball Club was founded in 1860 as an amateur organization. It was an open secret that the club began paying its players after the Civil War. After the loss of third baseman Henry Schafer to the new Boston club, the Athletics signed native son Levi Meyerle, a tall, powerful hitter, to take his place.

One team that fell out of the pennant race could point to two enduring accomplishments. Troy’s Haymakers finished in the middle of the pack at 13-15 but provided professional baseball’s first Hispanic player in third baseman Esteban Bellán, as well as the first Jewish professional ballplayer, Lipman Pike, who batted .377 and tied for the league lead in home runs.

Chicago won its first 19 games, including seven league contests, before losing to New York’s Mutuals on June 5 before 10,000 spectators at Brooklyn’s Union Grounds. The Athletics’ impressive array of hitters kept them in the race. However, on August 30, the Athletics succumbed to the visiting White Stockings, 6-3‚ the club’s lowest run total since it started professional play. Chicago pitcher George “The Charmer” Zettlein held the Athletics to four hits.

On September 11, Chicago topped the standings with a 17-6 record, trailed closely by the Athletics (17-7) and Boston (15-9). Yet because neither games won and lost nor the resulting percentage decided the champion, the important fact at this point of the season was that Boston and Chicago had each won three series from other clubs and lost none, while Philadelphia had won three but lost one, to Boston.

As the season wore on, the Athletics were hobbled by injuries. Center fielder John “Count” Sensenderfer — any player who was a favorite of the ladies was invariably nicknamed thus — went out for the year with a knee injury. Second baseman Al Reach — who like Boston’s Al Spalding would go on to create a sporting-goods empire — sat out crucial contests in the final days. Pitcher Dick McBride missed three straight games in September.

Heading into the home stretch, Boston had only six games to play to complete all of its series and, by sweeping them, win the championship. But the Red Stockings lost a critical game at Chicago on September 29, giving the interclub series to Chicago. On October 7, Boston rebounded to defeat Troy to claim that series.

On October 8 at about 9:00 P.M., the great Chicago Fire began. As it raged on October 9, ultimately killing hundreds, and destroying four square miles of the city, the Athletics defeated Troy, 15-3. The White Stockings were still in the race, but the conflagration had cost them their ballpark, their equipment, their uniforms and, it appeared, their livelihoods.

The Chicago players decided not only to play their scheduled National Association games in the East, but also exhibitions that could be hastily arranged. Wearing borrowed uniforms of varying hues and styles, they won often enough; however, they were clobbered in a game at Troy on October 23 that might have secured the championship. At one point they trailed by 14-0. The final score was 19-12.2

The weather was bad for Chicago’s Eastern swing; most of the club’s exhibitions were canceled, and the deciding game with the Athletics, scheduled for Brooklyn’s Union Grounds, was postponed several times before finally taking place on October 30. An Athletics win would give them the pennant outright; a Chicago win would throw the race into a tie, with Boston re-entering the computation.

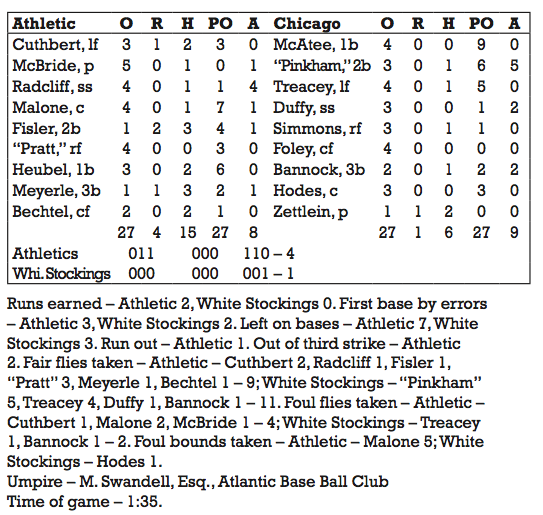

The game started at 3:10 P.M. Marty Swandell of the Brooklyn Atlantics umpired. Because of windy and damp conditions, only 600 fans occupied the grounds that had welcomed 10,000 in June when Chicago played the Mutuals. Chicago appeared in suits of various origins, ragtag in the extreme. Mike Brannock wore a complete Mutual uniform, except for the belt, which was that of the Eckfords. Center fielder Tom Foley was attired in a complete Eckford suit. Zettlein wore a huge shirt with a mammoth “A” on the bib, no doubt from the Brooklyn Atlantics. Shortstop Ed Duffy appeared in a uniform borrowed from the junior Fly Aways. Some Chicago players wore black hats, others were bareheaded.

“Certainly, a word of commendation should be given to ‘Pratt’ (not Tommy) who played right field for the Athletics. He used to play base ball years ago, and he handled the ash and ran after the balls with all the uncouth rusticity of a bygone age.” — New York World, October 31, 18713

The Athletics were shorthanded. Without the services of Reach, Sensenderfer, and reserve Tom Pratt, they fielded only eight men. First baseman Wes Fisler took Reach’s spot at second base and outfielder George Heubel came in to play first base. Veteran amateur Nate Berkenstock, a founding member of the Athletics who had not played in a game since 1867, was drafted into service. At the time, he was serving as Philadelphia’s team treasurer. Positioned in right field, and playing under the name of “Pratt,” the 39-year-old made a fine inning-ending running catch in the fourth inning to save two runs. Tremendous applause greeted his catch. He played errorless ball, making two other catches.

Philadelphia took the lead with a run in the second inning when Meyerle singled home Fisler. Errors by Duffy and Zettlein produced an unearned run for Philadelphia in the third inning. A defensive lapse in the seventh by Chicago’s first baseman, Bub McAtee, led to Philadelphia’s third run.4 In the eighth, Meyerle’s third hit of the game scored Fisler, who had singled and moved into scoring position on a hit by Heubel.5

Meyerle’s three hits gave him a season-ending batting average of .492, the high-water mark in professional baseball history. With one more hit he would have hit .500 for the season! He tied for the league lead in home runs (4). In 26 games, he drove in 40 runs while scoring 45. His .700 slugging percentage was not bested until 1920.

The hero of the game was McBride. Pitted against Zettlein, who allowed only two earned runs himself, McBride took a 4-0 shutout into the final frame.

Battling to avert a “Chicago” — a shutout synonymous with their city through a famous 9-0 blanking by the Mutuals on July 23, 1870 — Zettlein sent a hot grounder to Meyerle at third, which he kicked over to shortstop John Radcliff. Radcliff picked up the ball and made a try for the putout at first but threw wildly. Zettlein moved to second on the errant throw, advanced to third on a groundball by McAtee, and scored on a groundout by Jim Wood, playing as “Pinkham.” As the cheering for Chicago’s icebreaking run subsided, Fred Treacey flied out to Berkenstock to end the game. The applause at the end of the game was as much for the plucky fight of Chicago as it was for the championship secured by the Athletics.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes and Baseball-Reference.com, the following have been used in the completion of this story:

“Base Ball: White Stockings vs. Athletic,” Brooklyn Daily Times, October 31, 1871: 3.

“Our National Game: White Stockings vs. Forest Citys, of Cleveland,” Chicago Republican, May 9, 1871: 4.

Notes

1 “Base Ball: The Game in Chicago,” New York Clipper, April 29, 1871: 6.

2 “Base Ball: White Stockings vs. Haymakers,” Brooklyn Daily Times, October 24, 1871: 3.

3 “Athletics Victorious,” World (New York), October 31, 1871: 2.

4 “The Championship Won: The Philadelphia Boys Bearing Off the Pennant,” Sun (New York), October 31, 1871: 3.

5 “The Last Championship Match,” New York Clipper, November 4, 1871: 2.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 4

Chicago White Stockings 1

Union Grounds

Brooklyn, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.