October 4, 1944: Galehouse, Browns surprise Cardinals in opener of ‘Trolley World Series’

Ohio Governor and Republican candidate for vice president John W. Bricker posed for photographers before the game with two fellow Buckeyes, Cardinals manager Billy Southworth and Browns skipper Luke Sewell. Pressed by a reporter for a series prediction, Bricker simply grinned and said, “I hope St. Louis wins.”1

Ohio Governor and Republican candidate for vice president John W. Bricker posed for photographers before the game with two fellow Buckeyes, Cardinals manager Billy Southworth and Browns skipper Luke Sewell. Pressed by a reporter for a series prediction, Bricker simply grinned and said, “I hope St. Louis wins.”1

The first intracity World Series outside of New York since Chicago’s Cubs and White Sox squared off against one another back in 1906, and the first single-park series since the Yankees and Giants shared the Polo Grounds in 1922, came as a something of a shock to most baseball observers. The Cardinals had been expected to take their third straight NL flag in 1944 and did, in handy fashion, finishing 14½ games ahead of the Pittsburgh Pirates and winning 105 games. The Browns, though, had surprised nearly everyone by winning 89 games and taking the American League pennant by a single game over the Detroit Tigers on the final day of the season after blowing a seven-game lead in August. The Browns’ sizzling finish, which included 11 wins in their last 12 games, had some predicting the upstart AL squad to win the World Series, but Sewell’s announcement the day before the opening game had many rethinking the odds.

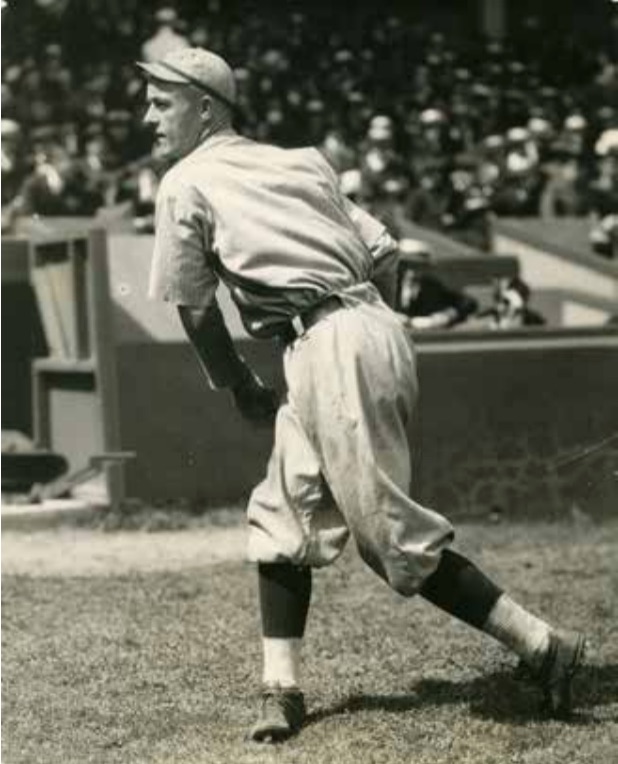

Sewell bypassed his ace, Nelson Potter, winner of 19 games, in favor of journeyman hurler Denny Galehouse for Game One. The right-handed Galehouse had put together an 81-88 won-lost record in his 10 years in the major leagues and had gone just 9-10 in 1944, pitching most of the season only on Sundays, when he would travel by overnight train to St. Louis from his defense job in a Goodyear Aircraft plant in Akron, Ohio.

When asked by reporters why he’d selected Galehouse to start, Sewell declined to explain, commenting only that “Galehouse is my man.”2

Galehouse likely made an impression on Sewell by winning two of three starts down the stretch. After a six-hit, 3-1 victory over the Philadelphia Athletics, Galehouse yielded only one run in five innings in losing at Boston. His last outing, a five-hit, 2-0 whitewash of the Yankees on September 30, kept the Browns even with Detroit and set the stage for their pennant-clinching win over New York on October 1.

“It’s the biggest thrill of my life,” Galehouse said. “I’ve yearned for this through the 15 years I’ve been playing ball but never came close.”3

The opposing moundsman came as a surprise to no one. The Cardinals’ Mort Cooper was a 20-game winner for the third straight season, compiling a 22-7 record with a stingy 2.46 ERA and seven shutouts, which tied him with Detroit’s Dizzy Trout for the most in the majors.

The weather was cool and damp that morning, but by game time, 2:00 P.M., the sun was out and the skies clear.

Series-opening festivities were subdued in keeping with wartime sensibilities, and outside of Governor Bricker, visiting dignitaries were few. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis, who was ill, remained in Chicago, missing his first World Series since he assumed the office in 1920.4 With 33,242 fans filling the stands, and tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of GIs listening on shortwave radio sets as they attempted to breach Germany’s Siegfried Line at Aachen or sweltered in the South Pacific, the Cardinals took the field.

The Cardinals were the first to threaten when Marty Marion doubled down the third-base line with two outs in the bottom of the second inning and Emil Verban singled sharply to center, sending Marion to third. Mort Cooper took a called third strike, though, to end the threat.

Cardinals center fielder Johnny Hopp may have deprived the Browns of a scoring opportunity in the third when, after a walk to Galehouse, Don Gutteridge lifted a fly ball to center. Hopp stumbled but recovered in time to make the catch.

The Cardinals threatened again in the bottom of the third when Hopp drove a one-out single just out of reach of George McQuinn’s glove at first, and Sanders’ drive to right field clanked off the glove of a sprinting Gene Moore. Hopp moved to second on what was scored a base hit.

Southworth called on Stan Musial, the NL leader with 51 doubles and a .990 OPS, to bunt. It was a perfect sacrifice. Galehouse, who scooped it up, could only toss the ball to McQuinn at first, with Hopp and Sanders advancing to second and third.

Walker Cooper, Mort’s brother and batterymate, was intentionally passed to load the bases, and as Bob Muncrief began to warm up in the Browns bullpen, Whitey Kurowski fouled off Galehouse’s first two pitches, and then went down swinging on the third. Danny Litwhiler then grounded to third, and the Browns’ Mark Christman made the force play unassisted for the third out.

In the top of the fourth inning, Chet Laabs took Mort Cooper deep to right field, but Musial made the catch at the wall. Vern Stephens popped out to second for the second out, but Moore followed by poking a single between first and second for the Browns’ first hit of the game.

George McQuinn stepped up to the plate. Cooper’s first pitch was high and inside for a ball. The next pitch was over the plate, and McQuinn connected, driving the ball onto the roof of the right-field pavilion for a two-run homer. The crowd, clearly leaning to the long-hapless Browns, erupted, and Moore and McQuinn were mobbed by their teammates as they crossed home plate. In the tumult, home-plate umpire John “Ziggy” Sears was forced to temporarily halt play until the crowd settled down enough to allow Christman to step in and ground out to shortstop Marion to end the inning.

Neither team managed a hit through the next three innings. With Ray Sanders on first and one out in the fifth inning, Browns second baseman Don Gutteridge executed what was called the “smartest play of the game.”5 Jogging back for Musial’s soft fly, he chose to let the ball bounce. He tossed the ball to shortstop Vern Stephens, covering second, who relayed to McQuinn at first for the inning-ending double play.

With the score still 2-0 in the bottom of the seventh and Augie Bergamo, who had drawn a walk batting for Emil Verban, on first, Mort Cooper, who had pitched seven innings of two-hit ball, was lifted for a pinch-hitter. Debs Garms grounded out to first, advancing Bergamo, but Galehouse retired Hopp and Sanders, leaving Bergamo stranded at second.

Right-hander Blix Donnelly took the mound for the Cardinals in the eighth. Donnelly, a 30-year-old rookie who had contributed a 2-1 record with a 2.12 ERA in 27 games as a spot starter and reliever, retired the Browns in order in the eighth and ninth innings.

Marion led off the bottom of the ninth for the Cards by lining to center. Kreevich made a diving stab at the ball, snaring it in his glove for a moment before it popped out and Marion pulled into second with a double. Bergamo, who had remained in the game in left field, grounded out to Gutteridge for the first out, with Marion moving to third. Southworth sent left-handed Ken O’Dea to hit for Donnelly. O’Dea flied to Kreevich in center, while Marion tagged up and scored to pull the Cardinals within a run. Kreevich, though, pulled in Hopp’s fly ball to put the game away for the Browns.

The improbable Browns had won the first game in their first World Series. In the process, they had come out on top despite only two hits, the first team to win a World Series game with such a meek attack.

Denny Galehouse pitched all nine innings, yielding only seven hits and one run. Although he looked somewhat shaky in the early innings, Galehouse subsequently bore down, allowing only two hits over the final six innings.

“Did Southworth blunder when he called on Stan Musial to bunt?” asked sports editor Sid Keener in the next day’s St. Louis Star-Times.

“After it was all over,” Keener wrote, “and the fans walked slowly from the park, and the press box gathered to review the stunning defeat of the National League champions, one managerial flaw was noted in Southworth’s strategy.

“Two on, none down, and the Cardinals’ leading batter at the plate. Would you play the old army game of bunting for a sacrifice, or call out some inside stuff like the hit-and-run or let Stan Musial swing with full power and no strings attached? Southworth played it safety-first for the bunt and the sacrifice, and with Musial the batter, it is repeated.

“And this is the story of how two hits won over seven hits – how the Browns, baseball’s Cinderella ball club, captured the first game from their National League rivals.”6

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author also consulted the New York Times, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and The Sporting News.

Notes

1 F.W. Crawford, “Series Sidelights,” Indianapolis Star, October 5, 1944: 16.

2 Orlo Robertson, “N.L. Champs 2-1 in Opener, 20-9 for Title,” Des Moines Register, October 4, 1944: 6.

3 “Galehouse to Face Cooper,” Daily Chronicle (DeKalb, Illinois), October 4, 1944: 11.

4 Landis eventually checked in to St. Luke’s Hospital in Chicago, where he died on November 25 after suffering a heart attack.

5 “Bricker, at Series, Praises Gutteridge,” Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1944: 1.

6 Sid Keener, “Browns First Team in World Series History to Win Game on Two Hits; Galehouse Brilliant in the Clutch,” St. Louis Star-Times, October 5, 1944: 20.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Browns 2

St. Louis Cardinals 1

Game 1, WS

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, Mo

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.