September 11, 1918: Red Sox win their fifth World Series as Carl Mays stops Cubs

Attendance was down dramatically for Game Six of the 1918 World Series. The weather was cold (45 degrees overnight), but more likely there was confusion over whether the game would be played at all, given the ongoing dispute regarding compensation.1 The official attendance for what could have been — and proved to be — the final, clinching game was 15,238, less than half of Fenway Park’s capacity.2

Attendance was down dramatically for Game Six of the 1918 World Series. The weather was cold (45 degrees overnight), but more likely there was confusion over whether the game would be played at all, given the ongoing dispute regarding compensation.1 The official attendance for what could have been — and proved to be — the final, clinching game was 15,238, less than half of Fenway Park’s capacity.2

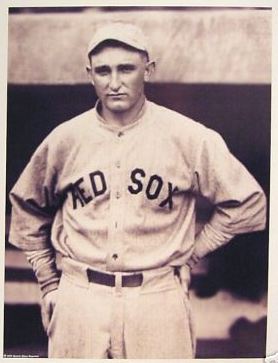

Game Three winner Carl Mays was given the game ball for the Boston Red Sox. With Lefty Tyler starting a third time for the Chicago Cubs, Boston manager Ed Barrow again had George Whiteman play left field and had Babe Ruth grab some bench.

Only one batter reached first base off Mays in the first three innings—Charlie Pick, who singled to left field but then was picked off first base in the second inning. Mays faced the minimum nine batters.

Amos Strunk singled in the first and Fred Thomas walked in the second, but the Red Sox really didn’t have anything going until the bottom of the third. Mays was quite a good hitter, with a .288 average in 1918, and he drew a four-pitch walk to lead off the inning. Harry Hooper did his job, bunting Mays to second. Dave Shean walked. Strunk grounded out to second but moved up both runners.

Whiteman was up. He hit the ball to Max Flack, who was becoming a bit of a hapless character in this Series when not at the plate. The right fielder let Whiteman’s liner play him—and what should have been a routine catch glanced off his glove. Both Mays and Shean scored on the error for a 2-0 Boston lead.

Perhaps, as the Washington Post’s J.V. Fitz Gerald suggested, Flack had run in too fast.3 Whatever the reason, he dropped the ball. Flack’s .263 average in the World Series was third best among Cubs batters and better than any Red Sox regular save catcher Wally Schang; Flack’s .417 on-base percentage was second best on the Cubs. But he’d dropped a two-out fly ball that should have ended the inning. It was the only time the Red Sox would score. The two runs were unearned, but they were enough to win the game.

The Cubs wasted no time before scoring themselves, and it was Flack who did so. He led off the top of the fourth with a single to center field and took second on Charlie Hollocher’s grounder to second baseman Shean. Mays then hit Les Mann, and the Cubs had runners on first and second.

Mann got careless and was picked off first base on a throw from Schang; it was the fourth time in the Series that a Cubs runner had been picked off base. Dode Paskert walked; without the pickoff, the bases would have been loaded. Flack then stole third base, but Paskert stayed on first. Fred Merkle’s single to left easily scored Flack, but Pick lined out to Hooper. It was Red Sox 2, Cubs 1.

The Red Sox also put men on first and second with one out in their half of the fourth, on Everett Scott’s single and Schang’s walk. Mays bunted safely and loaded the bases, but Hooper’s grounder to first base forced Scott at home plate. Third baseman Charlie Deal gathered in Shean’s grounder and stepped on the bag at third to force Mays. The score stayed as it had been.

After three groundball outs in the fifth, Mays walked Flack to lead off the sixth. But Hollocher forced Flack and then Mann forced Hollocher. And when Mann tried to steal, he was thrown out at second base. To go with their four pickoffs, the Cubs now had been caught stealing five times in the six games of the World Series. The Cubs were hitting the ball with a bit of authority, but the Red Sox fielders—including Mays himself, who had six assists in this game—plugged any holes. After the fourth inning, Chicago never hit safely again.

For that matter, the Red Sox were hitless as well after the fourth, save for a seventh-inning single by Strunk.

Whiteman had one more big play in him. Cubs manager Fred Mitchell turned again to Turner Barber to pinch-hit to lead off the eighth. Barber almost came through, hitting a ball that just got over Scott at shortstop. Seemingly a sure single, representing the tying run, the Cubs were stunned when Whiteman came out of nowhere and “grabbed the sphere below his ankles, and took a clean somersault, the great momentum rolling him up on his feet again.”4 He held onto the ball. It was such a spectacular catch that the thin crowd at Fenway cheered for as long as three full minutes. Whiteman apparently wrenched his neck on the play.

Another pinch-hitter, Bob O’Farrell, batted for Bill Killefer. He hit another ball that also looked sure to fall in, also into short left. Whiteman was still woozy and, in any event, not positioned to be able to get this one, but this time it was Scott who appeared to make a dramatic catch. Barrow prompted the crowd to offer up back-to-back ovations, once as Whiteman ran in to take a seat and again as Babe Ruth ran out to take his place in left. The third pinch-hitter of the inning, Bill McCabe, fouled out; it was shortstop Scott who had run all the way into foul territory to make the catch.

Claude Hendrix was back, this time as the pitcher he was, and he got all three Boston batters to fly out in the bottom of the eighth.

Mays was prepared to close it out in the ninth, facing Flack again in the leadoff slot. He had reached base twice in three plate appearances, but popped up foul to Thomas at third. Hollocher flied out to Ruth in left for the second out. Mann grounded out to Shean, who tossed to Stuffy McInnis at first base (the Boston Globe called him “Stuffy the Stretcher”)—and the Red Sox had won their third World Series in four years, fourth in the last seven seasons, and fifth of the 15 World Series played to this point.

Only one Cub reached second base after the fourth; Mays had thrown a masterful three-hitter. Tyler had allowed only five hits, but as the Globe noted, it was “a pair of walks, a sacrifice and Flack’s muff that developed the runs.”5

It was a surprising World Series. In six games, the Red Sox scored only nine runs—but won the requisite four games. They won with a team batting average of .186. Perhaps more importantly, they’d committed only one error in the entire six-game stretch and made the plays that counted. They had received excellent pitching from Mays (2-0) and Ruth (2-0) in particular. The team ERA was a collective 1.70.

The Cubs’ stats were similar enough: a remarkable ERA of 1.04 but a team batting average of only .210. Fred Mitchell was just being frank when he allowed, “I’d like to play the series over again if such a thing were possible. … I shall always contend that with an even break, we would have won.” He didn’t mean to detract from Boston’s win. “It was a tough series to lose,” he admitted. “All the glory that goes with winning the world championship belongs to Boston. The pitching on both sides was the best in years. … They are a great team and proved it.”6

Numerous columnists agreed that luck played a big role in such a close Series, and that the Red Sox had the better luck.

The Washington Post credited George Whiteman as the most valuable player of the game: he “single handed won the sixth and deciding game of the series. …Whiteman is the hero of the 1918 championship.”7

Boston kept tradition alive — no Boston team had ever lost a World Series. Of the 17 Series played to date, the Braves had won their one in 1914 and the Red Sox had won all five of theirs.

It wasn’t yet mid-September, but there was a war to win.8 Everyone hoped baseball might resume in the springtime.

The Cubs hadn’t won a World Series since 1908. Cubs fans hoped a win in the World Series would follow before too long.9

Boston fans naturally hoped the dominant Red Sox would continue to win world championships in the years to come.10

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org, and drew substantially on Bill Nowlin and Jim Prime, The Boston Red Sox World Series Encyclopedia (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008).

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BOS/BOS191809110.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1918/B09110BOS1918.htm

Notes

1 See the account of Game Five, on September 10, 1918.

2 Games Four and Five at Fenway had averaged 23,438.

3 J.V. Fitz Gerald, “Boston World’s Champion by Defeat of Chicago, 2 to 1,” Washington Post, September 12, 1918: 8.

4 Dick Jemison, “Red Sox Win Straw Hat Title,” Atlanta Constitution, September 12, 1918: 14.

5 Edward F. Martin, “Red Sox Win Sixth Game and the Title,” Boston Globe, September 12, 1918: 1, 8.

6 Edward F. Martin.

7 J.V. Fitz Gerald.

8 At the end of each inning throughout the game, carrier pigeons were released by two men from the Army Signal Corps to carry word on progress of the game back to the troops stationed at Fort Devens, just over 30 miles away. See Edward F. Martin.

9 The Cubs next won the World Series in 2016, after a wait of 108 years.

10 The Red Sox waited 86 years, until 2004, before winning the World Series again. The next time they won a World Series with the clinching game at Fenway Park was in 2018.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 2

Chicago Cubs 1

Game 6, WS

Fenway Park

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.