September 27, 1917: All-stars turn out for Tim Murnane benefit

Baseball’s modern business model has turned major league benefit games into relics. Formal corporate support to assist carefully screened causes is the norm today. From at least the inception of the National League-American League coalition in 1901 through the immediate post-World War II period, however, major league benefit games were common; wherever needs that attracted public interest arose, players were ready to take the field to help, and ownership made it happen.

Such was the case in Boston on September 27, 1917. The city’s baseball icon, Tim Murnane, had died suddenly earlier in the year.1 A fund had been established for his family, and the Red Sox, the American League, and the Baseball Writers’ Association of America worked with local businessman and former club owner John I. Taylor 2 to arrange a benefit exhibition matching the Red Sox with an all-star team.

Such was the case in Boston on September 27, 1917. The city’s baseball icon, Tim Murnane, had died suddenly earlier in the year.1 A fund had been established for his family, and the Red Sox, the American League, and the Baseball Writers’ Association of America worked with local businessman and former club owner John I. Taylor 2 to arrange a benefit exhibition matching the Red Sox with an all-star team.

Although eight of the sixteen major league teams were in scheduled action on this late-season Thursday afternoon, both the White Sox and Giants had clinched their respective pennants; those remaining games on the schedule meant little to them. The White Sox were poised to open the World Series nine days later in Chicago,3 yet two of their most valuable players—Joe Jackson and Buck Weaver—were in Boston for the benefit.

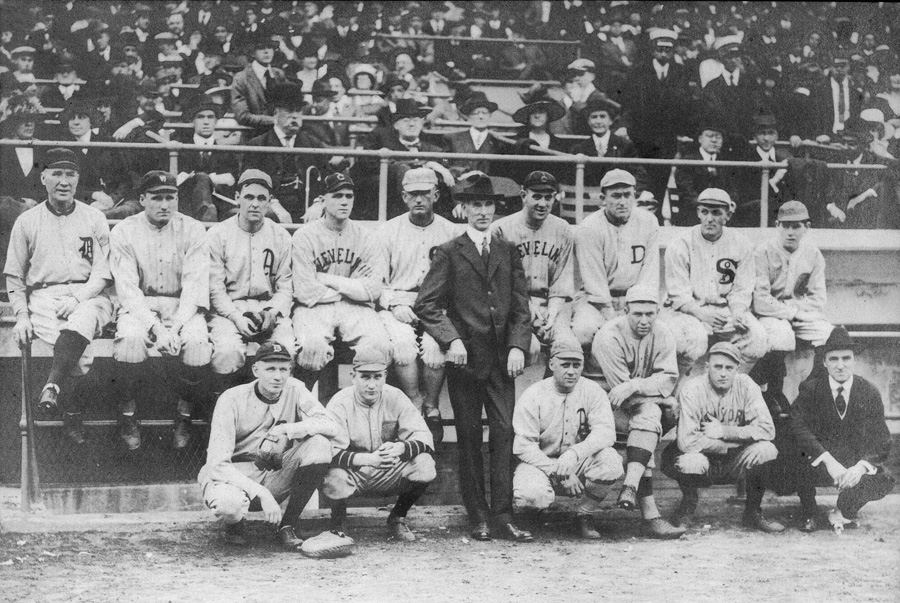

Each of the American League clubs except St. Louis contributed players. Rabbit Maranville of the crosstown Braves was the only National League representative. Grover Cleveland Alexander of the Phillies, Edd Roush of the Reds, and Benny Kauff of the Giants had been scheduled but bowed out for family reasons or because of injuries. But there were plenty of the biggest names in the game on “the fanciest picked team that ever trotted out from any bench.”4 In addition to Jackson and Weaver, former Red Sox favorite Tris Speaker, now with Cleveland; Ty Cobb; Walter Johnson; Ray Chapman; Wally Schang; and Stuffy McInnis made the trip and were backed up by Steve O’Neill, Howard Ehmke, Urban Shocker, and Bob Shawkey. The A’s Connie Mack and Detroit skipper Hughie Jennings were on hand to manage the Stars. And Boston’s own rising star, Babe Ruth, was set to start on the mound for the Red Sox.5

Weather deemed “perfect,”6 “a beautiful, warm, hazy, September afternoon,”7 greeted the 17,119 in attendance. The benefit committee had arranged an enticing set of pregame events—the Ziegfeld Follies road show was in town and lent popular entertainers Will Rogers and Fanny Brice to the festivities. A group of Follies chorines sold scorecards and helped the fundraising effort by “forgetting” to provide change. Former heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan, a Boston fixture, put in an appearance.

Baseball “field days” were in vogue at the time, and the committee offered the fans five events: timed bunt-to-first and around-the-bases contests, a distance throw, an accuracy throw8, and fungo hitting for distance. Ruth won the fungo event, and Jackson uncorked a distance throw of 396 feet, eight inches, to beat the second-place throw by 12 feet. “He took home an inscribed silver bowl as a trophy, and the bowl remained one of Jackson’s most treasured possessions for the rest of his life.”9

Although some sideline antics continued (with Rogers and Sullivan in the coaching boxes for the Red Sox from time to time, and the five-foot-five Maranville squaring off with Sullivan in a pugilistic pose) Tommy Connolly, dean of AL umpires, presided behind the plate, kept things straight, and the game was crisply played.10

Ruth struck out Cobb in pitching around a single, steal of second, and his own throwing miscue to strand Chapman at third in the Stars’ first inning. The Stars’ starter, Shocker, gave up a two-out triple to Red Sox first baseman Dick Hoblitzell in the bottom of the first but retired the next hitter, left fielder Duffy Lewis, to keep his slate clean. Ruth rolled along, yielding two more singles, including one to Cobb11 that didn’t leave the infield, but no runs, through five innings. Boston spot-starter Rube Foster took over in the sixth.

Shocker shut out the Red Sox for two more innings. Ehmke pitched the next three with the same result, although it took a strong throw from Jackson, then in center, to nip Hoblitzell at the plate in the sixth as he attempted to score on a single by Tilly Walker.

Shocker shut out the Red Sox for two more innings. Ehmke pitched the next three with the same result, although it took a strong throw from Jackson, then in center, to nip Hoblitzell at the plate in the sixth as he attempted to score on a single by Tilly Walker.

Johnson, then in mid-career with Washington and enroute to a 23-16 record for a club that finished under .500 in 1917, negotiated the Boston seventh to maintain the scoreless tie, but encountered trouble in the eighth. With two outs, Red Sox player-manager Jack Barry singled, Hoblitzell bounced another single over second, and Duffy Lewis scored them both with a ringing triple to center.12

That was the ballgame, as Foster held the Stars hitless through his four innings.

A week later The Sporting News praised the enterprise, tagging the game “vivid,” and “one of the best games seen [in Boston] this season; surely a high water mark as far as baseball benefit performances are concerned.”13

The “impressive and well-deserved tribute . . . a great occasion and a grand day’s sport”14 raised an amount estimated at between $13,000 and $15,000. The memorial fund used some of the proceeds to place a headstone at Tim Murnane’s grave, with an inscription concluding “erected by the American League.”15

Acknowledgments

This article was inspired by a mention of the game in the Epilogue to Fenway 1912 (Mariner Books, 2011) by Glenn Stout. Anyone even remotely interested in Red Sox history will appreciate the book’s meticulous coverage of the birth of Fenway Park in 1912 and that season of play there, which brought the Red Sox an American League pennant and a hard-fought World Series title. National SABR Vice-President Bill Nowlin took time from his busy schedule to gather and send me digitized newspaper accounts of the Murnane game played at Fenway five years later. Those contemporary accounts, including the elusive box score for the game, clarified points on which subsequently-published material differed. And SABR member Bill Lamb provided an arcane fact which had me stumped until it dawned on me to seek his Deadball Era expertise.

Sources

Fleitz, David L. Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2001), 135.

Ruth, Babe with William R. Cobb., ed. Playing the Game: My Early Years in Baseball (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2011), 37-38.

Stout, Glenn. Fenway 1912 (New York: Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), 339.

Eaton, Francis. “Red Sox Win Brilliant Game From All-Stars,” Boston Daily Advertiser, September 28, 1917.

O’Leary, James C. “17,000 Out To Honor Murnane, Red Sox Win Memorial Day Game, 2-0,” Boston Globe, September 28, 1917.

Whitman, Burt. “Red Sox and Stars Make Murnane Day Success,” Boston Herald, September 28, 1917.

Boston Globe, September 27, 1917.

Christian Science Monitor, September 28, 1917.

The Sporting News, October 4, 1917.

Bevis, Charlie. “Tim Murnane,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org, accessed June 11, 2014.

Stahl, John. “John I. Taylor,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org, accessed July 16, 2014.

“The Red Sox and Some Great All Stars Take the Field to Honor Tim Murnane,” Fenway’s Best Moments No. 81, fenwayparkdiaries.com, accessed June 12, 2014.

Thorn, John. “Tim Murnane, Heart of the Game,” ourgame.mlblogs.com, May 8, 2013, accessed June 12, 2014.

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Timothy Hayes Murnane, known in his later years as the “Silver King,” for his luxuriant mane of graying hair, died at age 65 on February 2, 1917. His Boston baseball connections were deep—he’d played with the city’s pioneer National League franchise in 1876 and 1877, then was a player-manager with the Boston Reds of the Union Association in 1884. He remained in the city, gravitated to sports writing, mainly with The Boston Globe, and by the time of his death was considered the dean of the Boston baseball press. (John Thorn, “Tim Murnane, Heart of the Game”; Baseball-Reference.com). Murnane had remarried after the death of his first wife and left four young children, for whom “his ambition was that [they] should be able to go to college when old enough.” (Francis Eaton, Boston Daily Advertiser, September 28, 1917).

2 Taylor had owned the Red Sox from 1904 through 1911 and maintained a partial ownership interest until 1914. (John Stahl, “John I. Taylor”).

3 The Red Sox won the World Series in 1912 and back-to-back in 1915 and 1916, but were in second place, 8 ½ games behind Chicago, and out of 1917 pennant contention by September 27. (Baseball-Reference.com).

4 Eaton.

5 Ruth, 22, and in his fourth major league season, was still primarily a pitcher in 1917. For the year he pitched and batted in 41 games and appeared as solely a hitter in another 11 games. He batted .325 with two home runs and 14 RBI in 142 plate appearances. (Baseball-Reference.com).

6 James C. O’Leary, Boston Globe, September 28, 1917.

7 Eaton.

8 The accuracy throw was from home plate to an open-ended barrel facing home, placed on a box at second base.

9 David L. Fleitz, Shoeless, The Life and Times of Joe Jackson, 135.

10 “The spirit of the All-Stars was immense. They seemed to get more fun out of the occasion than the fans, yet the ball game was a serious affair with both teams giving their best effort.” Burt Whitman, “Red Sox and Stars Make Murnane Day Success,” Boston Herald, September 28, 1917.

11 Cobb, Jackson, and Speaker, who wore his old Red Sox uniform for the occasion, alternated in the outfield positions each inning throughout the game. (Eaton).

12 As a baseball writer, Murnane had particularly appreciated Lewis’s skills, calling him “a sweet hitter.” (O’Leary).

13 The Sporting News, October 4, 1917.

14 O’Leary.

15 Charley Bevis, “Tim Murnane,” quoting the June 19, 1919, Boston Globe.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 2

Major League All Stars 0

At Fenway Park

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.