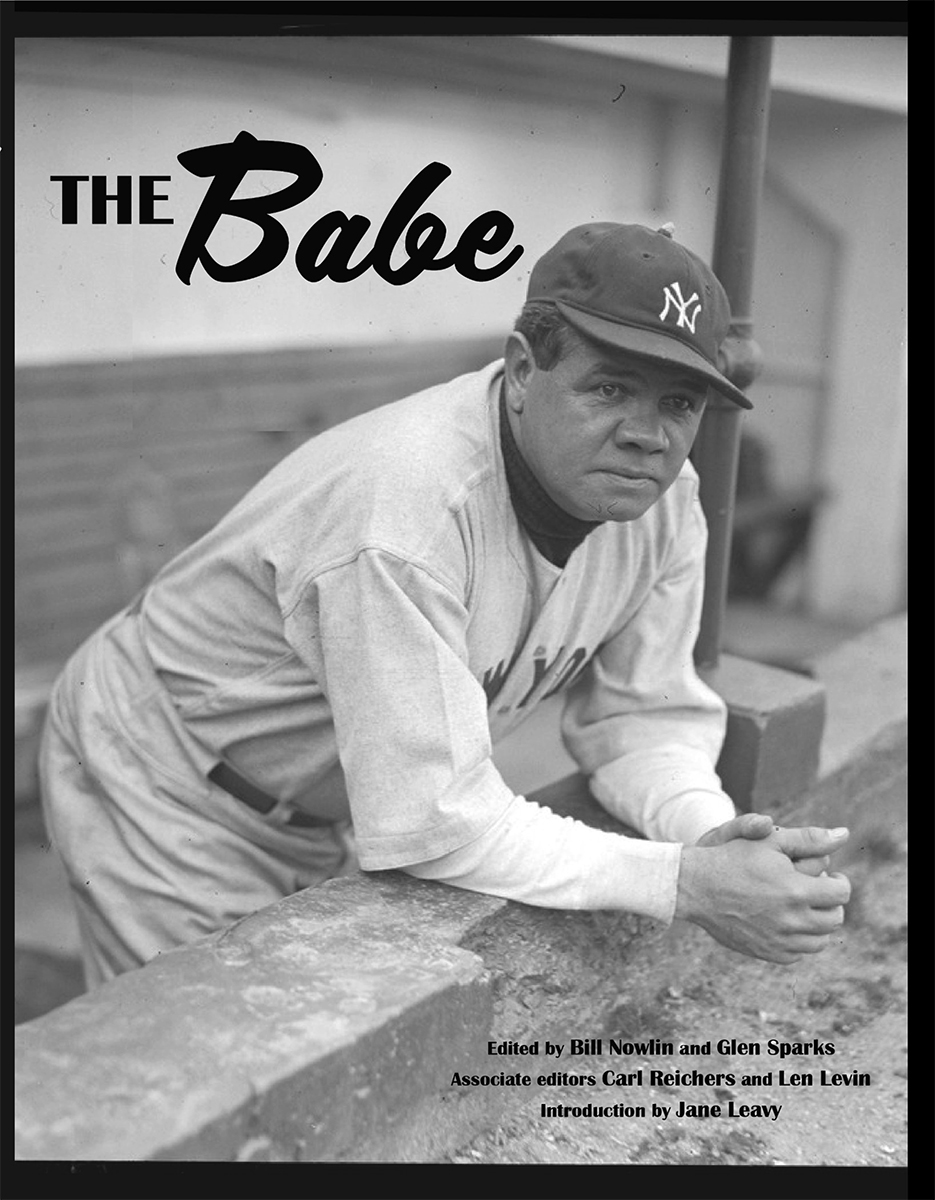

Babe Ruth Characterizations — and Caricatures

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

Granted, numerous screen biopics have charted the lives of ballplayers from Hall of Famers to major leaguers with unusual, marketable life stories.1 One legend – Lou Gehrig – has been portrayed twice, in 1942’s The Pride of the Yankees and A Love Affair: The Eleanor and Lou Gehrig Story, a 1977 made-for-television movie. Another – Jackie Robinson – has been featured in two theatrical films (1950’s The Jackie Robinson Story and 2013’s 42) as well as a host of others, starting with a pair of TV movies (1990’s The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson and 1996’s Soul of the Game).

Granted, numerous screen biopics have charted the lives of ballplayers from Hall of Famers to major leaguers with unusual, marketable life stories.1 One legend – Lou Gehrig – has been portrayed twice, in 1942’s The Pride of the Yankees and A Love Affair: The Eleanor and Lou Gehrig Story, a 1977 made-for-television movie. Another – Jackie Robinson – has been featured in two theatrical films (1950’s The Jackie Robinson Story and 2013’s 42) as well as a host of others, starting with a pair of TV movies (1990’s The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson and 1996’s Soul of the Game).

But what about The Babe? To date, the life of The Sultan of Swat has been charted in three features; he is played by actors as diverse as William Bendix (in 1948’s The Babe Ruth Story), Stephen Lang (in Babe Ruth, a 1991 TV movie), and John Goodman (in 1992’s The Babe). He appears in 1993’s The Sandlot (played by Art LaFleur), A Love Affair: The Eleanor and Lou Gehrig Story (Ramon Bieri), and Dempsey, a 1983 made-for-TV biopic (Michael McManus); in The Sandlot, he offers sage advice that any youngster should ponder as he pronounces, “Remember kid, there’s heroes and there’s legends. Heroes get remembered but legends never die. Follow your heart, kid, and you’ll never go wrong.”

Decades later, Jonathan Winters enacts The Bambino in The Babe and the Kid, a seven-minute short from 2009; in 2014’s Henry & Me, an animated feature, he is voiced by Chazz Palminteri. He has been featured in innumerable documentaries; a typical title is 2013’s I’ll Knock a Homer for You: The Timeless Story of Johnny Sylvester and Babe Ruth. Indeed, The Babe’s across-the-decades fame is epitomized in Whip It, released in 2009: the tale of a female roller-derby player who nicknames herself “Babe Ruthless.”

Bambino portrayals are not limited to the movies. In 1984, The Babe – a one-man show featuring Max Gail – came to Broadway; it eventually was taped and shown on ESPN. Here, three stages of Ruth’s career are presented: The Babe in his prime; upon his retirement; and at an Old Timers game. But the show failed dismally. “That ‘The Babe’… is so wide of the mark, is no small feat,” opined Mel Gussow in the New York Times. “(It’s) an evening of bush league Babe.”2 The production was sent to the showers after eight previews and five performances.3

Two years later, The Babe and Libbie Custer, a dinner-theater vehicle based on a play by Bob Broeg, premiered in St. Louis, with Gilio Gherardini playing The Babe. “I thought maybe the public would accept my fictional meeting between two people who had pulled themselves out of a slump,” Broeg declared. As noted in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “(Broeg) has Ruth talk about the mistakes he has made in his personal life and his career, with engaging candor.”4 But The Babe and Libbie Custer never did make it to the Great White Way.5

Of primary interest here are the three Babe Ruth biopics, each of which offers a decidedly distinct portrayal of its subject. They depict The Sultan of Swat in relation to the time in which each was produced, combined with the then-prevailing view of its subject. The Babe Ruth Story, for example, was scripted and produced when certain insiders were aware that its subject was fatally ill; it came to theaters weeks before his death. Beyond the fact that the film is all-out dreadful cinematically, it is a revisionist biopic that is the equivalent of a 106-minute-long press release. Its story respectfully charts The Babe’s life, from his Baltimore youth and time at St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys to his rise with the Red Sox, his switch from pitching to hitting, his arriving in the Bronx, his on-field heroics and records, his aging, and his being inflicted with a nameless fatal malady. Helen, The Babe’s first wife, is nowhere to be found. Instead, he is shown to fall deeply in love with Claire (Claire Trevor), his real-life Wife #2; the two first meet when she correctly detects the reason for a pitching slump.

The Babe in this story is a naïve but well-meaning athlete whose good intentions are overridden by poor judgment. He is victimized from the outset: His youthful problems result from his harmlessly belting balls through storefront windows. While at St. Mary’s, he is spellbound and compliant. Upon his stardom, he is a friendly kidder; never is he foolhardy or self-absorbed, and never does his behavior cross the line between good-natured joking and outright vulgarity. His issues with Miller Huggins (Fred Lightner) are linked to the skipper’s failure to comprehend The Bambino’s concern for others; onscreen, Huggins is depicted as an ego-driven squirt who unjustly chastises his ballplayer without learning the facts.

At one point, the ballplayer fails to make the Yankee Stadium starting lineup because he assists a young fan and his injured dog. In a sidesplittingly dreadful sequence, The Babe lines a batting practice pitch which hits the pooch. “Don’t let my little dog die!” pleads its freckled, pint-sized owner. So The Bambino whisks the kid and his pet off to a hospital, where its life is spared. “Ah, gee, Babe, you’re wonderful!” the boy adoringly tells the Yankee. However, upon returning to the team after missing the game, he is fined and suspended – and is labeled by the media as the “Bad Boy of Baseball.” After a couple of gamblers offer him money to throw a game, he belts them both – and finds himself detained for beating up “two innocent bystanders.” As he lies dying, he contorts in pain after being casually struck on his back. An elevator operator responds by jesting that The Babe surely has imbibed “one too many.”

The onscreen Bambino unfalteringly supports the sport, even after he is duped out of a Boston Braves vice presidency. He responds to a proposal that he sue the Braves by retorting, “That would be like suing the church.” And he rejects an offer to manage the Yankees’ minor-league Newark franchise solely because it would result in the dismissal of the current skipper. As for The Babe’s controversial “called shot” in the 1932 World Series, not only is the feat acknowledged but supposedly happened because he had guaranteed a seriously ill youngster that he would “sock a home run into the center field bleachers.” While at bat, Claire loudly reminds her husband, “Don’t forget Johnny.” The Bambino tips his cap and points to the outfield. After taking two strikes, he signals yet again before belting the dinger.

At its worst, the content in The Babe Ruth Story is unintentionally comical, never more so than when a crippled boy and his father gaze at The Bambino as he smashes a 600-foot homer during spring training. After a friendly greeting from the ballplayer, the kid miraculously rises to his feet. “They said he’ll always be an invalid,” his disbelieving father declares. “Spend his life on his back. Now look at him. Just look. Oh, God bless that man. God bless him!”

Conveniently, neither Lou Gehrig nor the infamous Ruth-Gehrig feud appear in The Babe Ruth Story. But the Iron Horse is referenced: In a prelude, some youngsters lower their heads upon learning of Gehrig’s fate while visiting the Baseball Hall of Fame. This recognition comes off as an awkward add-on, as if to negate the discomfiture of excluding Gehrig from the film’s main section.

In the concluding sequences, The Babe is felled by an unnamed illness and, even as he is dying, his self-effacement is overwhelming. While hospitalized, he humbly declares that he receives “so much mail (that it) makes me feel important.” He accepts an untried serum that has been tested only on animals. It might speed his passing, but he agrees after being informed that “(if) it works it might help other people.”

Another flaw in The Babe Ruth Story is the casting of William Bendix. An otherwise fine character actor, Bendix was 42 when he played The Bambino; he was especially miscast in his scenes as a St. Mary’s teenager. Robert Creamer, the Babe Ruth biographer, was spot-on when he observed, “For thousands of people, maybe millions, William Bendix in a baseball suit is what Babe Ruth looked like. Which is a terrible shame, because lots of men look like William Bendix, but nobody ever looked like Babe Ruth. Or behaved like him.”6

Compared with The Babe Ruth Story, The Babe rates as an all-time-ten-best Hollywood classic. In reality, however, the film is a conventional sports tale that is elevated by the appealing presence of John Goodman and its pleasing production design. The film is hyped for being based on the true events that occurred in the ballplayer’s life between 1902 and 1935. It clearly is a post-Production Code biopic7 in that it emphasizes its subject’s famed excesses (as well as his failed first marriage). He is shown to possess a Ruthian carnal craving; he frolics with a 16-year-old, passes time with hookers, and spends an evening with four women in a New Orleans brothel. But his actions are not all sexual. At one juncture, he requests that a woman pull on his finger. She does, and The Bambino noisily passes wind.

During Marriage #1, he and his spouse have sex three times in a single day – and The Bambino is anxious for a fourth tryst. However, Helen (played by Trini Alvarado) is an ordinary young woman who likes animals and loathes The Babe’s socializing. Predictably, their union is ill-fated. The Babe sleeps with Wife #2 (Kelly McGillis) prior to his divorce; she is a sophisticate, a Ziegfeld Follies showgirl who is acquainted with Al Capone and is not at all bothered by her husband’s lifestyle. She acknowledges and understands this; she loves him, appreciates him better than he appreciates himself, and is a loyal pal even when The Babe is written off as an aging fool.

One intriguing aspect of The Babe involves his final three big-league homers, which he belted in a single game at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field while playing for the Boston Braves. The team owner views the aging Bambino as “a circus act, a sideshow,” but the homers allow the man who smashed them to leave the field with a special grace. As he exits, he is oh so conveniently met by a grown-up Johnny Sylvester; earlier, the ballplayer dashed off to young Johnny’s hospital bed and delivered on a guarantee to smash two homers for the youngster. “I’m gone, Johnny. I’m gone,” he tells Sylvester, in a line whose variation actually was uttered to Joe Dugan several weeks before his death.8

Unlike The Babe Ruth Story, The Babe in no way sentimentalizes its hero. Ruth’s youth is one of hopelessness and meanness. St. Mary’s is presented as a dreary environment, not dissimilar to a juvenile detention facility; he is taunted mercilessly by the other boys and beaten by the Brothers. Later on, he expresses his desire to one day manage the Yankees, but this never occurs as he cannot transcend his reputation for lacking self-restraint. The Babe queries Jacob Ruppert (Bernard Kates), “Ty Cobb is managing. Tris Speaker. Why not Babe Ruth?” The owner tells him, “How can you manage a team when you can’t even manage yourself?” Eventually, The Bambino is offered the Newark manager spot, but he refuses because he considers the offer an affront – not out of concern for another man’s unemployment.

Additionally, the Ruth-Gehrig friction is acknowledged in The Babe. The Bambino senses that the Iron Horse (Michael McGrady) will challenge his status as a living Yankee legend and detests the younger player from his time as a rookie. The Babe even purposefully refers to the first baseman as “Gallagher,” perhaps out of jealousy. However, The Babe never purports to offer a psychological analysis of its central character. It only presents the events in a man’s life, his personal idiosyncrasies, and his achievements and setbacks.

Babe Ruth is the least of the trio, if only because of its made-for-TV status. It premiered several months prior to the theatrical release of The Babe, and it differs from The Babe and The Babe Ruth Story as it spotlights The Bambino’s life after his arrival in New York. Additionally, never once is the ballplayer depicted at the bedside of an ailing child.

Stephen Lang, an actor with a lengthy list of stage, film, and TV credits, makes an effective Babe, playing him as an overgrown child who wins acclaim for his athletic feats but fails to embrace maturity. Both his wives are present; plus, Pete Rose is smartly cast in a cameo as – who else? – Ty Cobb! Babe Ruth originally was written with John Goodman in mind, but the Roseanne star left the project upon being offered The Babe.9 Goodman’s choice distinguishes between the high-profile A-list major studio features and the under-publicized TV fare that defined the era.

*****

Babe Ruth does not always appear by name onscreen, but his fame and larger-than-life personality have combined to make him fodder for caricature in a range of films. Each reflects the manner in which The Bambino was viewed at specific moments in time.

Slide, Kelly, Slide and Casey at the Bat were both released in 1927, near the end of the silent film era, when The Babe already had won fame as a super-celebrity with an over-the-top ego. With a cunning wink at the viewer, the central characters in each exude more than a bit of The Bambino.

Clearly, Jim Kelly (played by William Haines), the protagonist in Slide, Kelly, Slide, is Ruthian in his demeanor. He is both a world-class pitcher and home run hitter; at the finale, our previously banished hero tosses a gutsy game and smashes an inside-the-park dinger. Off the field, Kelly is a detestable showoff who boasts that he can hurl two baseballs at once; on his business card, he dubs himself “Jim ‘No Hit’ Kelly.” Plus, he is a trickster with a juvenile sense of humor who passes around exploding cigars and wears a water-squirting carnation. He regularly defies his manager, just as The Bambino battled with Miller Huggins, and thoughtlessly flirts with women. At one juncture, he even practically date-rapes his girlfriend. But he is beloved by the fans, and he loves kids.

The specifics of the plotline also unite fact, fiction, and myth. Kelly’s team is the New York Yankees, and Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri appear onscreen during spring training. (However, some Yankee links predate the production of Slide, Kelly, Slide. One of the Yankees is a catcher by the name of “Pop” Munson [Harry Carey]. Kelly also exhibits a fondness for a ragamuffin [Junior Coghlan] who becomes the team mascot. His name is Mickey Martin, a clever combination of Mickey Mantle and Billy Martin.)

The central character in Casey at the Bat, Mike Xavier Aloysious Casey (Wallace Beery), also is a Ruthian parody. The film, set in the 1890s, is a slapstick adaptation of the Ernest Lawrence Thayer poem. Here, Casey is an overly extravagant, none-too-bright small-town junkman who is signed by the “Noo York Giants” and soon becomes “‘Home Run’ Casey, the man who owns Broadway.”

Beery’s farcical, larger-than-life performance is the film’s centerpiece. His Casey belts massive home runs and also possesses a yen for beer and chorus girls. Upon coming to New York, he would rather swig champagne and ogle Florodora girls parading across a stage than prepare for the next Big Game. Despite his acclaim, Casey is at his core an illiterate hick. He may dress himself in a fancy suit, but its oversized buttons result in his resembling a yokel. And back home, he comes to the plate with a bat in one hand and a pitcher of beer in the other. The country-mile dinger he belts is what lands him a big-league contract.

As in Slide, Kelly, Slide, Casey also has a special affinity for children. At one point, he is queried about throwing a big game. “If I’d strike out today,” he growls, “every kid in America would know I done it on purpose. Now get out!”

Casey at the Bat and Slide, Kelly, Slide are not the lone features with Babe Ruth influences. They stretch across the decades: Even though he is a heavy, one of the characters in Warming Up (1928) is McRae (Philo McCullough), a trickster and home-run king who, as noted in Variety, is “supposed to be the prototype of Babe Ruth.”10 The Whammer (Joe Don Baker), a slugger who is fanned on three pitches by Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford) in The Natural (1984), is a blatant Ruthian inspiration. At the time, writer-producer-director Garry Gross envisioned generating a biopic featuring Baker as The Babe. “I never saw two people who look so much alike,” Gross declared.11 However, the project never came to fruition.

Arguably the gloomiest caricature is found in Deadline at Dawn (1946), a murder-mystery. If The Babe is lionized in The Babe Ruth Story, here he is depicted as a pathetic drunk named Babe Dooley (Joe Sawyer), a baseball star who stalks the urban byways deep into the night in search of a dame called Edna. “Edna, it’s The Babe. Babe Dooley,” he yells up at her apartment. “Why don’t you open the door for your Babe?” Then he self-pityingly mumbled to himself, “Nobody loves a fat man.”

Later on, Dooley returns to Edna’s street. “Edna! It’s The Babe. Are you home, Edna?” he asks. “It’s late. I can’t get a drinkie anywhere. Throw down a bottle, will ya?” Two policemen arrive to check the commotion he is causing, and their demeanor changes from brusque to accommodating upon realizing Dooley’s identity. “Hey, it’s The Babe, Babe Dooley,” one declares. His partner chimes in, “Nothin’s too good for The Babe,” while the first officer asks, “Are we gonna cop the pennant this year, Babe?” But Babe Dooley is obsessed with copping nothing more than his “drinkie.” Observes another character (played by Joseph Calleia), “There’s a fat ballplayer who some night will die in the streets.”

Which depiction is more reflective of the real Bambino: Babe Ruth in The Babe Ruth Story or Babe Dooley in Deadline at Dawn? The answer, perhaps, is somewhere in between. …

ROB EDELMAN (1949-2019) was the preeminent expert on the history of baseball in film and cinema, publishing countless articles and several books on that subject. He was the editor of SABR’s From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors in 2018, and also wrote Great Baseball Films and Baseball on the Web.

Notes

1 The former includes Dizzy Dean (in 1952’s The Pride of St. Louis); Grover Cleveland Alexander (1952’s The Winning Team); Roy Campanella (1974’s It’s Good to Be Alive, a made-for-television movie); and Satchel Paige (1981’s Don’t Look Back: The Story of Leroy “Satchel” Paige, also made-for-TV). Among those in the latter are Monty Stratton (1949’s The Stratton Story); Jimmy Piersall (1957’s Fear Strikes Out); Ron LeFlore (1978’s One in a Million: The Ron LeFlore Story, also a TV movie); Pete Gray (1986’s A Winner Never Quits, also made-for-TV); Jim Morris (2002’s The Rookie); and Moe Berg (2018’s The Catcher Was a Spy).

2 Mel Gussow, “‘The Babe’ at Princess,” New York Times, May 18, 1984.

3 ibdb.com/broadway-production/the-babe-4338.

4 “‘The Babe and Libbie Custer’ Opens,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 10, 1986.

5 Babe Ruth has been endlessly depicted in art and song, in novels and radio plays. For a thorough list, see James Mote’s Everything Baseball (New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1989).

6 Shirley Povich, “A Qualified Thumbs-Up for ‘The Babe,’” Washington Post, May 17, 1992.

7 Further information on the history of the Motion Picture Production Code may be found at: productioncode.dhwritings.com/multipleframes_productioncode.php.

8 Tracy Brown Collins, Baseball Superstars: Babe Ruth (New York: Checkmate Books, 2008).

9 Bart Mills, “Stephen Lang Gives The ‘Babe’ His Best Shot,” Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1991.

10 Variety, June 27, 1928.

11 Variety, March 3, 1982.