Babe Ruth Visits Louisville

This article was written by Harry Rothgerber

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

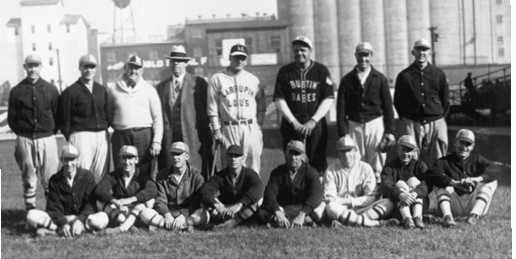

Parkway Field, with the iconic Ralston Purina grain silos visible past the right field wall, was the site of benefit game between the Bustin’ Babes and Larrupin’ Lous in 1928. Ruth and Gehrig are flanked by some of the top local amateur ballplayers from Epps Cola and Beck’s Lunch who comprised their teams. (Used with permission of Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory.)

Louisville, Kentucky, has a wide array of historical credentials on its baseball résumé: charter member of the National League; the infamous scandal of 1876; 10-year member of the major-league American Association, followed by eight more years in the National League; home of Pete Browning; birthplace of Hillerich & Bradsby Company’s Louisville Slugger bats; home of Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory; site of Honus Wagner’s rookie year; Eclipse Park, Parkway Field, Cardinal Stadium; home of Pee Wee Reese; the Colonels’ minor-league success in the American Association and IL; the million-fans Redbirds attendance record; current Louisville Bats; and Louisville Slugger Field, to list the highlights.

Add to that résumé the following credit: an age-old and ongoing love affair with Babe Ruth. In his lifetime he visited Louisville on at least five occasions for a variety of reasons: barnstorming money; loyalty to the Xaverian Brothers who raised him; presidential politics; golf with Bud Hillerich’s PowerBilt clubs; and raising money for storm relief. His presence in the city was always appreciated and respected by the locals.

A closer examination of those visits begins by looking back more than 100 years ago.

August 15, 1921

Louisville Colonels 3, New York Yankees 1

With much anticipation and great fanfare, the New York Yankees arrived by train at Louisville’s Union Station at 7:35 A.M., and Babe Ruth began a day of whirlwind activity.1 A former teacher at Baltimore’s St. Mary’s Industrial School, where Ruth was raised, was instrumental in arranging this visit by his now-famous pupil.

In 1917, Brother Benjamin Burke, C.F.X., a member of the Catholic religious order of teachers known as the Xaverian Brothers, had become principal of St. Xavier’s College (now St. Xavier High School) in Louisville.2 It appears that, with Ruth’s support, he worked for two years to persuade both leagues involved to reschedule games so that the Yankees could arrange a midseason visit.3 In 1925 Brother Ben, as Ruth called him, would return to Baltimore and become St. Mary’s superintendent, always maintaining a close friendship with Ruth.4

The local council of the Knights of Columbus, the international Catholic fraternal organization, quickly whisked Ruth and the Yankees away for a mini-tour of the city for the rest of the morning, followed by a stop at noon at the Louisville Industrial School, a residential placement for dependent, delinquent, and orphaned children.5 This facility was part of the local House of Refuge,6 a combination reformatory/orphanage that appears to have been similar to St. Mary’s. Dressed in a suit and tie, Ruth took part in a “pitching contest” and was struck out by Edward Miner, one of the young wards there.7

The 3:00 P.M. exhibition game at Eclipse Park between the Yankees and the Louisville Colonels featured two first-place ballclubs – the Yankees led the American League as the result of Cleveland’s loss to the White Sox the day before, and the Colonels owned a three-game lead over Minneapolis in the American Association.8

In conjunction with this event, the Hillerich & Bradsby Company purchased a newspaper advertisement titled “Babe Ruth’s Bat a Louisville Slugger,” noting that “Ruth’s bat is 36 inches long and weighs 47 ounces.” Accompanied by a photo of him, the ad copy read, “Like most Famous Sluggers of the national game, Ruth uses exclusively bats made by the Hillerich & Bradsby Co. He has found that Louisville SLUGGER bats have the spring, balance and driving power needed to slug them over the fence.”9

On a partly cloudy day with a high of 78 degrees, Louisvillians jammed Eclipse Park for the event. Reserved seats had been sold out for days; temporary stands had been put up to seat the overflow patrons; and more people were allowed to stand in a roped area in the deep outfield, just behind the outfielders. Eventually, 12,081 fans were counted in attendance in a ballpark that had 7,500 seating capacity, with virtually every man wearing a straw bowler and dark suit, in the style of the day.10 Before the game, Colonels player-manager Joe McCarthy – the same future Hall of Famer who would deftly manage the Bronx Bombers from 1931 to 1946 – accepted a silver loving cup from a local sporting-goods company.11 It is likely that this is the first time that Ruth laid eyes on the so-called “bush-leaguer” who would become his manager in a mere 10 years.

As for the game itself, the two teams engaged in an underwhelming struggle, with the Colonels faithful exulting in a 3-1 victory. The news headlines captured much of the story: “Colonels Triumph Over Yankees Before Record Crowd” and “Babe Ruth Fails to Hit in Four Times Up; Strikes Out Twice.”12

For the Colonels, left fielder Roy Massey was the batting hero, going 2-for-4 with three RBIs, while catcher Fred Hofmann scored the only run for the Yankees in the ninth on a double followed by an error.13 Outfielder Ruth played first base, and many of the New York regulars were given the day off, as second-stringers dominated the lineup.14

Although Kentucky native Carl Mays had been expected to pitch for the visitors, he did not play.15 Colonels pitchers Ernie Koob, Tommy Estell, and Tommy “The Windmill” Long held their opponents to only three hits, with Long striking out Ruth to end the game.16 Ruth swung at all three pitches in an attempt to propel another ball out of the park as he had already done 44 times against AL pitching.17

After the game, which lasted only 1 hour and 22 minutes, Ruth had no time to rest. At 6:30 P.M. he appeared at St. Xavier’s Park in a contest at which all boys under 16 years old were invited. Ruth, himself a member of the Knights of Columbus, took 24 baseballs autographed by the grand knight of the local council and batted them into the assembled group of lads who scrambled for the valued souvenirs. To continue his day of frenetic activity, he was honored at an evening dinner that the Knights sponsored.

At the conclusion of dinner, Brother Benjamin and the Knights accompanied the major leaguers to the train station, and the Yankees traveled 115 miles north to Indianapolis for an exhibition the next day. Meanwhile, the Colonels departed for Milwaukee and an exhausting 31-day stint on the road.

In the following days, a number of letters to the editor appeared in the newspaper. One angry fan commented, “It was a rotten game on the visitors’ side. … I did not want to pay out my money to see a big tub like Babe Ruth stand up to the plate and put up a stall like he did Monday, especially the last time at bat. I expect he thought everybody paid their money just to look at his big frame, but I did not for one. …”18 In response, another fan wrote, “… any baseball fan who was there knows that he saw a sure enough, hard fought baseball game, and not a one-sided contest by any means. This game was anybody’s until the last man was out in the ninth. … Messrs. Huston and Ruppert are willing to pay him fifty thousand dollars per year for displaying his ‘big frame.’”19 Finally, a Louisvillian concluded, “I confess I was disappointed with Monday’s game, but I thoroughly enjoyed the batting practice.”20

In a later accounting of the profits of the day, the Yankees received $4,436.15, the Colonels received $2,436.15 and St. Xavier’s was given $2,000.21

Season’s end saw the Yankees win the AL pennant but lose the World Series to the Giants. Ruth amassed astounding numbers, including 59 homers and a .378 batting average. “Brainy” Joe McCarthy’s Colonels, later described as “unquestionably one of the most powerful Louisville teams ever assembled,” won the American Association pennant and then shocked Jack Dunn’s dominant Baltimore Orioles by a margin of five games to three in the Junior World Series.22

June 2, 1924

Louisville Colonels 7, New York Yankees 6

Babe Ruth, now firmly established as the nation’s leading athlete-personality, led the defending world champions into town for their second Louisville appearance. Two days earlier, in the second game of a doubleheader, he had been knocked unconscious in a collision with Yankees second baseman Ernie Johnson. In typical Ruthian style, he recovered to homer later in the game.23

However, a native Kentuckian on the Yankees roster also attracted attention. Right fielder Earle Combs had graduated from Eastern Kentucky State Teachers College in 1921 and taught school until the Colonels signed the college slugger in 1922. After two stupendous years at the plate – batting .344 and .380 – the popular player known as the Kentucky Colonel was signed by the Yankees and had a superb start in his first season.24 A future Hall of Famer, Combs would spend 12 seasons with the New Yorkers, mainly as a leadoff center fielder.

Once again the city rolled out the red carpet for the major leaguers, but a different venue awaited the two teams. Eclipse Park, wooden home of the Colonels for 21 years, had been destroyed by fire in November 1922.25 The team’s new ballpark was Parkway Field, a concrete and steel structure built in only 63 days and opened on May 1, 1923. It would be the home venue until 1957.26

The first-place Yankees arrived from New York by train at 11:45 A.M. As Ruth alighted from the train dressed in a “somberly blue striped suit” for his official welcome, he encountered a group of Confederate veterans on their way to a reunion in Memphis. They cheered him, and a photograph memorialized their chance meeting. After a hurried shave and lunch, he was taken to the ballpark, accompanied by a parade of cars, for the 3:00 game.27

Similar to three years earlier, there was extraordinary fan interest in the game, with some people clinging to telephone poles for a view. Before the game a Knights of Columbus official delivered an armload of roses to Combs and a silver service to Ruth, who, in turn, gave prizes to six youngsters who had triumphed in a local track and field event. Although Ruth was unable to visit St. Xavier’s on this trip, the St. Xavier junior team players watched the game as special invitees.28

As for the game, the crowd of 9,986 received a daily double of excitement: The home team came from behind for a victory, and Ruth blasted a ninth-inning right-center-field homer that many believed to be the longest ball ever hit out of the ballpark.29 It landed in a gas station on the corner of Shipp and Eastern Parkway, well over 500 feet away.30 His other plate appearances resulted in a foul out to the catcher; a fielder’s choice; a single and a groundout. Earle Combs also went 2-for-5, including a double, to please the home folks. Colonels pitchers Ernie Koob and Tommy Estell continued their mastery of the visitors.

Ruth’s day was far from over when the game concluded after 1 hour and 28 minutes. First, he was off to the downtown Sutcliffe’s sporting goods store where he handed out yellow mini-bats to more than a thousand youngsters who had earned a free ticket to the game by enlisting a new subscriber to the daily Courier-Journal.31 After that, an unusual assignment beckoned: He journeyed a few blocks to the offices of the newspaper and joined sports editor Bruce Dudley in the composing room, where Ruth assisted in designing the following day’s sports stories and pages.32 In a late-night interview, he commented, “If I am any judge of a ball player, Combs will be a super star.”33

Combs too was busy after the game – but at a different sporting-goods store. It was Earle Combs Day at Roe-O’Connor’s, where an Earle Combs mini-bat was distributed to each customer, and the Yankee himself was on hand to give a free rule book to each child.34

By 11:00 P.M., Ruth was on a train for Chicago, where he was scheduled for an X-ray of the rib that he hurt earlier in the week.35 Whatever that result, he led the Yankees to a 6-3 victory over the White Sox the next day, going 2-for-3 with two RBIs and a run scored.36 Meanwhile, the Colonels left for the next day’s league game in Columbus.37

Although the Louisville men won 91 games that season, they finished in third place in the American Association and failed to make the playoffs. The Yankees won 89 games and finished in second place in the AL, two behind Washington.

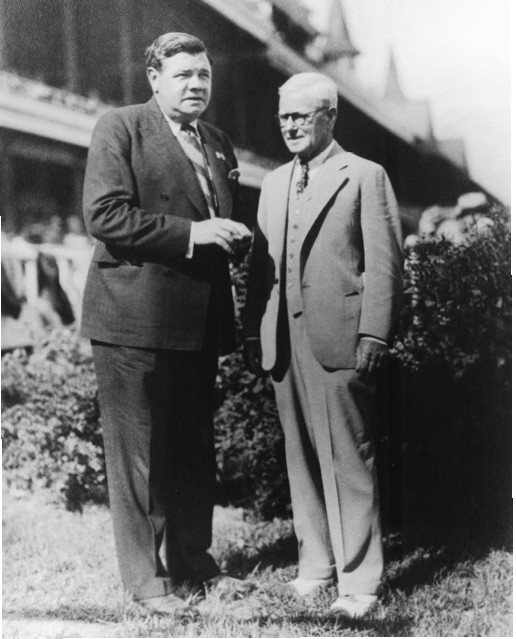

Eleven months after his retirement, Ruth attended the Kentucky Derby as a guest of his friend, Louisville bat-maker Bud Hillerich. Note the famous Twin Spires of Churchill Downs in the background. Barely visible in this view are the bandaged forefinger and thumb which Ruth contrived to deter autograph-seekers. (Courtesy of Churchill Downs Racetrack)

October 24, 1928

Bustin’ Babes 13, Larrupin’ Lous 12

On September 17, 1928, the deadly Okeechobee hurricane struck Florida at West Palm Beach, leaving a trail of death and destruction. As a result, the Courier-Journal and the Louisville Times engineered a postseason visit by Ruth and Lou Gehrig to benefit the Red Cross Florida Storm Relief Fund.38 Two weeks earlier, the Yankees had completed a four-game sweep of the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series.

Ruth was scheduled to play first base for the Bustin’ Babes – actually Epps Kola, the top amateur team in the city – while Gehrig would perform with the Beck’s Lunch team, renamed the Larrupin’ Lous for the occasion.39

A busy day awaited. At 1:40 A.M., the train carrying the two Yankees arrived in town from Columbus, Ohio, site of their previous day’s game. Rising at 8:00 A.M., they were given a brief tour of the downtown area, including a stop at St. Xavier High School.40 There, Ruth immediately recognized Prefect of Studies Brother Bernard, one of his former teachers at St. Mary’s.41 Brother Bernard was quoted as saying, “George, my boy, you certainly have grown into a fine, big fellow since the days when you came romping into my classroom. …” To which Ruth replied, “Yes, brother, I guess I have changed quite a bit, but you haven’t. … Although it has been years since I saw you, I recognized you the minute I walked through the door.”42 Ruth addressed the St. X students, an event that was later memorialized in the school’s yearbook.43 The sportswriter Christy Walsh – Ruth and Gehrig’s agent – was also there.44

After stops at City Hall and the Hillerich & Bradsby Company, maker of their Louisville Slugger bats – where Ruth persuaded owner John A. “Bud” Hillerich to give him a new set of golf clubs45 — the two stars ate breakfast at the Kentucky Hotel, with Ruth ordering two of everything “except beans.”46 At noon, they were guests of the Kiwanis Club for lunch. Then they were driven to Parkway Field for the 2:00 game.

A paid crowd of 3,270 – distinctly fewer than in previous years – made their way to the ballpark in clear weather and 62 degrees.47 Schoolchildren with a note from their parents were excused by the Board of Education to attend the game.48 Ruth’s team won a 13-12 decision as he slammed two home runs – including one inside-the-park – two doubles, and a single, while Gehrig clubbed one homer and a single. The two Yankees each pitched the last three innings for their respective teams.

A shortage of baseballs almost caused an early finish to the exhibition. Nine dozen baseballs were on hand at the start of the game, but by the eighth inning, all but one had been used. After the last one was fouled into the stands, a young fan had to be “induced” to give it back so that the game could go on.49 (Babe had been prescient in this regard. A subheadline in the newspaper the day before read, “Babe Asks for 120 Baseballs – Slugger Thinks He and Lou Need That Many in City Game.”50)

With the game over in 1 hour and 50 minutes, Ruth and Gehrig, after eating, still had political commitments to fulfill. In the downtown Jefferson County Armory, a popular assembly place, Ruth addressed a packed house and extolled the virtues of his friend New York Governor Al Smith, who was the Democratic nominee in the coming presidential election.51 After he finished his impassioned speech (“Don’t forget what the Yanks did to Philadelphia when all the experts said the Yanks were through. …”) and sat down, his chair broke under him. However, disaster was averted when he grabbed a railing and prevented himself from falling off the speaker platform.52 John W. Davis, the Democratic nominee for president four years earlier, spoke after him. (“I agree with Democracy’s best batsman. …”)53

Ruth, joined by Gehrig, then walked a block to the auditorium of the historic Seelbach Hotel and spoke to a meeting of the Kentucky Young Men’s Democratic League.54 Although they had declined an invitation to take part in the Kentucky State Fox Hunt, it was still quite a hectic day for the two stars, described as “skilled fox hunters who seldom pass up an opportunity to indulge in one of their favorite pastimes.”55

In any event, the gate receipts enriched the Storm Relief Fund by $500; Ruth said that he had never autographed that many balls during a single day;56 and the two Yanks left by train to participate in a similar exhibition in Dayton, Ohio, the following day.57

April 4, 1932

New York Yankees 9, Louisville Colonels 6

This game marked the triumphant return to Louisville of a key member of the Yankee team – Joe McCarthy, in his second year as manager. He had spent 10 seasons with the Colonels, including seven at the helm, during which he won two pennants and one Junior World Series and had the team mostly in contention. Hired by the Cubs after the 1925 season, Marse Joe, as he came to be known, had yet to win a major-league World Series, although his Cubs won the 1929 NL pennant. His former player Bruno Betzel now managed the Colonels.

This exhibition game was a preseason affair, with both teams playing their way north after spring training. A day earlier, Colonels pitching held the visiting Cincinnati Reds to five hits in a 5-3 Louisville victory, while the New Yorkers trounced the Memphis Chicks, 17-4, after which they immediately left on a train for the Derby City.58

Despite their second-place American League finish in 1931, Ruth, Gehrig, and Combs still generated excitement wherever they played. The crowd that awaited their arrival at Central Station by the Ohio River was disappointed to learn that the Yankees had instead arrived at Union Station on Broadway, then proceeded to the nearby Kentucky Hotel.59

Prior to the afternoon game, Ruth made an appearance at a noon assembly at St. Xavier High School, where his old friend Brother Benjamin had once again become principal in 1931.60 When St. X freshman Joe Wells addressed the Yankees slugger as “Mr. Ruth,” he recalled what happened next: “… And with that, he shot back at me and said, ‘You call me “Babe,”’ and then he and Brother, they were laughing. They got a kick out of it. … So, anyway, we got off half a day, and most of us went out to Parkway Field to see the game. …”61

Before the game McCarthy took the field to an ovation from the 5,810 fans in attendance and was presented with a gold baseball manufactured by local jeweler Albert Grall.62 Izzy Goodman, McCarthy’s friend and former King of the Colonel Boosters, ended the pregame activities by giving him a large garland of roses.63

Although the April day was pleasant with a temperature of 73 at game’s end, the fielding in the two-hour game was ugly. The hometown team outhit the visitors 14-11, but the Colonels also managed to make seven errors (to the Yankees’ two), leading to a 9-6 New York victory. Gehrig and Combs went hitless in a combined 11 trips to the plate, but Ruth singled and doubled in five plate appearances, driving in three runs. Yankees right fielder Ben Chapman was a home run short of the cycle while pitcher Gordon Rhodes, relieved by Ivy Paul Andrews, picked up the victory. The Colonels hurlers Clyde Hatter (who took the loss), Archie McKain, and Eldon McLean gave up only one hit – a single –in the final four innings.64

Destinations were varied. In the short term, the Yankees headed 106 miles to Cincinnati for their exhibition against the Reds the next day, while the Colonels awaited the Chicago White Sox for games on April 5 and 6. In six months Ruth would be bound for his historic “called shot” game against the Cubs, helping the Yankees capture another World Series – the first of seven for manager McCarthy, who had been dismissed by the Cubs management two years earlier.

April 29 to May 2, 1936

The Kentucky Derby

Instead of baseball bats, golf clubs were in Babe Ruth’s hands during his next visit to Louisville. Upon arriving at 11:33 A.M. on Wednesday of Derby Week with his wife, Claire, and daughter, Julia, Ruth said, “I’ve been waiting 20 years for a chance to see the Kentucky Derby, and here I am.”65 The 62nd running of the “greatest two minutes in sport” was three days away.

Eleven months after his final appearance as a player, Ruth was in town as the guest of John A. “Bud” Hillerich, the man who transformed his father’s woodworking company into one that manufactured the bats used and endorsed by the Yankees slugger.66 They had been friendly for some years: In 1918, Ruth sent a thank-you note to Hillerich after the latter paid him a $100 endorsement fee to place his signatures on Louisville Slugger bats;67 15 years later, Ruth personally invited Hillerich to attend a dinner he gave at the New York Athletic Club to celebrate the All-American Board of Baseball writers who helped select Ruth’s annual “All-American teams.”68 Then in October 1934, Hillerich and his wife, Rose, had accompanied 14 major-league players and their families, including Babe, Claire, and Julia, on their trip to Japan, where the “Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig All-Stars” went 17-0.69 After the series, Bud and Rose joined the Ruths, Lefty and June Gomez, and a few others as they continued their trip around the world, visiting Java, Bali, Egypt, Venice, Paris, St. Moritz, and London.70 Expanding his PowerBilt golf-club line, Hillerich provided Ruth and other players with free clubs for offseason play in Florida.71 No doubt personal bonds were formed over the years due to these connections.

Two hours after stepping off the train and checking into his suite at the Kentucky Hotel, Ruth was playing 18 holes at Audubon Country Club, where Ward Hillerich, Bud’s son, was three-time defending club champion. Ruth’s partner in the best-ball competition was Bobby Craigs, the club professional and a future member of the Kentucky Golf Hall of Fame. Hillerich was paired with Wild Bill Mehlhorn, a noted touring professional who had 20 wins on the PGA tour.72

Ruth was passionate about golf, and he played quite frequently.73 For example, during the 1932 offseason, he played well at the West Coast Open tournament, leading the amateurs.74 His powerful swing and marvelous hand/eye coordination served him well on the golf course.

However, Ruth and his partner were bested by Hillerich’s team, 3 and 2, on that first day at Audubon, despite his drive that went 300 yards on the fourth hole. Individual scores were also kept, and Ruth shot an 84. One observer said, “The Babe cracks the ball like a willowy kid despite the tremendous depth and breadth of his chest and shoulders.” Ruth called for a rematch, vowing to do better now that he had played the course.75

Before play began the next day, Ruth was made an honorary member of the Kentucky Association of Left-Handed Golfers.76 On the course, the public had been invited to what he called “a grudge match,” and, in front of a gallery of spectators, he improved his score to 80, with his team winning, 1-up. Amazingly, he had been allowed a six-stroke handicap!77

Setting his golf clubs aside on Derby Eve, Ruth was invited by Bud Hillerich to be his guest at a different sporting event, and he spent the evening at the boxing matches in the downtown Armory.78 Refereed by boxing legend Jack Dempsey – also now retired – the 10-round, nontitle main event pitted Barney Ross, the world welterweight champion, from Chicago, against Chuck Woods from Detroit, ranked sixth in that division. Ruth joined a crowd of 4,118 and saw Ross manhandle Woods, knocking him out in the fifth round.79

Other celebrities were present that night; in fact, the largest ovation was not directed at Ruth – he finished third in that comparison, behind crowd favorite Dempsey and Joe E. Brown, the popular wide-mouthed comic film star. All three were invited into the ring prior to the main event to briefly address the crowd, and they were involved in a bit of tomfoolery with each other.80

Another significant Kentucky personality was present that evening – A.B. “Happy” Chandler, then early in his first term as governor, who brought 50 of his political friends with him.81 That evening may have been the beginning of the friendship that was forged between Ruth and Chandler, who became commissioner of baseball in 1945. In that future capacity, Chandler was a tearful visitor to a cancer-ravaged Ruth in the hospital; proclaimed April 27, 1947, to be Babe Ruth Day in every Organized Baseball ballpark; and was a speaker on that very day in Yankee Stadium when Ruth personally appeared.82

On a partly sunny, 78-degree Derby Day, Ruth and his wife shared a box out in the open with their host, Bud Hillerich; the Dempseys were seated not far away.83 Ruth had a history of being besieged by autograph seekers when he came to Louisville; he remembered the vast numbers of baseballs that he autographed when he was in town in 1928.84 He handled that possibility in unique Ruthian manner, according to Bud’s son Junie: Before going to the track, Ruth put a bandage on his right thumb and forefinger and told autograph hounds that he hurt his hand in the elevator the night before.85 Photographs support that story and the inference that left-handed-batting Ruth signed with his right hand.86

That wasn’t the only trickery he perpetrated that day – he put one over on his wife, too. Well-known for the fiscal responsibility that she brought to their marriage, Claire kept a close eye on his betting. Babe wanted to place a $5,000 wager on the odds-on favorite, Brevity, and he did so by sneaking away from Claire before they went to the Downs and calling his bookmaker in New York.

Ruth didn’t leave his seat all day except for a brief time to place a legal parimutuel wager on Brevity, and Claire was happy with his apparently responsible behavior. After Brevity finished second in the big race to Bold Venture, a 20-to-1 longshot, she became suspicious and questioned Babe about whether he had bet on the race. He confessed that he did, and he showed her the $10 ticket. Claire was very delighted – as was the bookie back home.87

Afterword

It appears that Babe never returned to the Derby City after that stay, but his memory lived on at Hillerich & Bradsby. Their advertising manager Jack McGrath recalled, “Ruth was an easy guy to please with bats. … Ruth seldom broke a bat, but he bought more of our bats than any ballplayer that ever lived. He gave so many away.”88 As a mark of his personal friendship with Bud Hillerich, Ruth always posed with the familiar H&B “Louisville Slugger” trademark logo showing on the bat he was holding.

Three months prior to Ruth’s death at the age of 53 in August 1948, it was reported that he would possibly return to Parkway Field in July as the guest of Bruce Dudley, then president of the Colonels, in conjunction with an American Legion baseball tournament.89 He and Dudley were longtime friends from the days when the latter was the sports editor of the Courier-Journal and would accompany the youthful winners of Ruth’s All-American Contest to meet the Babe in person.90 In light of the serious nature of Ruth’s medical condition, such a Louisville visit was wishful thinking at best.

Louisville’s love for Babe Ruth, begun almost 100 years ago, continues to this day. One of the most viewed items at popular Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory is a bat that he used during one of his baseball-bashing seasons. He carved 21 notches on it – one for each home run he hit.91 Outside of the factory/museum rests the world’s largest baseball bat. Made of steel, it weighs 68,000 pounds and reaches 120 feet into the sky. According to curator Chris Meiman, “The Big Bat is an exact-scale replica of Babe Ruth’s R43 Louisville Slugger bat.”92

HARRY ROTHGERBER, a SABR member since 1983, has led the Pee Wee Reese Chapter for 20 years. A former member of the national SABR Board of Directors, he served as co-chair of the successful 1997 national convention in Louisville, Kentucky. Harry collects books by and about Babe Ruth, and his own work Young Babe Ruth was published by McFarland in 1999. An attorney by profession, he works as a prosecutor and writer and lives in Louisville with his wife of 50 years, Helen.

1 “ ‘Full House’ To Greet Baseball’s Champion Slugger Today,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 15, 1921: 6.

2 Brother John Joseph Sterne, Growing in Excellence: The Story, Spirit and Tradition of Saint Xavier (Louisville: ikonographics, Inc., 1989), 93.

3 “Full House.”

4 Brother Gilbert, C.F.X.; edited by Harry Rothgerber, Young Babe Ruth: His Early Life and Baseball Career (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., Inc., 1999), 184-185. “Ruby’s Report,” Louisville Courier-Journal, April 5, 1940: 39. “Brother Benjamin Greeted as Principal at St. Xavier,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 25, 1931: 4.

5 The Encyclopedia of Louisville, s.v. “Orphanages,” 679-681.

6 Ibid.

7 “Even Mighty ‘Babe’ Is ‘Struck Out,’ ” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 16, 1921: 3.

8 “Full House.”

9 Ibid.

10 “Full House”; Bruce Dudley, “Babe Ruth and Earle Combs Strut Stuff at Ball Park Today,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 2, 1924: 9. “Colonels Triumph Over Yankees Before Record Ball Crowd,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 16, 1921: 6. “Ruby’s Report,” Louisville Courier-Journal, January 31, 1946: 17.

11 “Colonels Triumph”: 6, 7.

12 “Colonels Triumph”: 6.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 “Full House.” “Colonels Triumph”: 6.

16 “Colonels Triumph”: 6,7.

17 Ibid.

18 A Constant Reader, “Monday’s Baseball Game,” Point of View column, Louisville Courier-Journal, August 18, 1921: 4.

19 R.J.H., “Pro-Ruth #2,” Point of View Column, Louisville Courier-Journal, August 20, 1921: 4.

20 A Local Fan, “Pro-Ruth #3,” Point of View Column, Louisville Courier-Journal, August 20, 1921: 4.

21 “Profitable Day for Yankees,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 18, 1921: 7.

22 Philip Von Borries, The Louisville Baseball Almanac (Charleston, South Carolina: History Press, 2010), 51.

23 “Yanks Break Even With Phillies; Babe Knocked Out, Then Gets Homer,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 1, 1924: 60.

24 Richard B. Lutz, “Earle Combs: Louisville Colonel and Gentleman,” A Celebration of Louisville Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues (Pittsburgh: Matthews Printing, 1997); Dudley, “Babe Ruth and Earle Combs.”

25 Anne Jewell, Baseball in Louisville (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006), 36.

26 Jewell, 39, 60-61.

27 “10,000 Cheer Babe Ruth as Ball Sails Over Parkway Field Fence,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 3, 1924: 1, 3; “It Was a Perfect Day! Ruth Hit Homer and Colonels Won,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 3, 1924: 9.

28 “St. Xavier Cubs Win Tenth Straight,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 1, 1924: 59.

29 Bruce Dudley, “Mighty Babe Crashes Longest Hit in Louisville Baseball History,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 3, 1924: 9.

30 “Men With Louisville Ties Made Strong Impact on Career of Ruth,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 17, 1948: 15.

31 Dudley, “Babe Ruth and Earle Combs Strut Stuff,” 10. “10,000 Cheer,” 3.

32 “ ‘King of Swat’ Will Appear at Parkway Field This Afternoon,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 2, 1924: 1. “10,000 Cheer”: 1, 3.

33 “It Was a Perfect Day”: 9. This is the earliest use of the term “super star” that the author has found.

34 “Earl [sic] Combs Day at Roe-O-Connor’s Monday,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 1, 1924: 62.

35 “10,000 Cheer”: 1.

36 “Yanks Combine Own Hits With Errors of White Sox to Capture First, 6-3,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 4, 1924: 7.

37 Dudley, “Babe Ruth and Earle Combs Strut Stuff,” 10.

38 “Ruth, Gehrig to Come Here From Columbus for Contest,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 23, 1928: 13.

39 Ibid.

40 “Ruth and Gehrig to Exhibit at Parkway Field Today,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 24, 1928: 13.

41 “Former Teacher Greets Babe,” Louisville Times, October 25, 1928: 1.

42 Ibid.

43 Senior Class of St. Xavier High School, The Tiger, 1934, 45.

44 Sterne, 105.

45 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Ruth Set Autographing Mark Here; Teams Beg Back Last of 108 Balls!” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 18, 1948: 17.

46 Pete Johnson, “Babe Asks for 120 Baseballs,” Louisville Times, October 24, 1928: 1.

47 “Ruth and Gehrig Delight 3,270 Baseball Admirers Here,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 25, 1928: 17.

48 “Ruth and Gehrig to Exhibit”: 14.

49 “Ruth and Gehrig Delight”: 18.

50 Pete Johnson.

51 “ ‘Babe’ Declares ‘Al’ Has Earned Victory,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 25, 1928: 1.

52 “ ‘Babe’ Declares”: 2.

53 “ ‘Babe’ Declares”: 1.

54 “ ‘Babe’ Declares”: 2.

55 “Ruth, Gehrig to Come Here From Columbus”: 13.

56 “Ruth and Gehrig Delight”: 17-18.

57 “Babe, Lou in Dayton After Showing Here,” Louisville Times, October 25, 1928: 2.

58 “Colonels Beat Reds by 5-3 and Are Ready for Yankees,” Louisville Courier-Journal, April 4, 1932: 8, 9.

59 “Marse Joe’s Yankees Here, Play Colonels,” Louisville Times, April 4, 1932: 1.

60 Bruce Dudley, “Colonels Outhit Yankees but Lose on Errors by 9 to 6,” Louisville Courier-Journal, April 5, 1932: 11.

61 Joe Wells, tape-recorded interview, September 8, 1997.

62 Bruce Dudley, “Colonels Outhit Yankees”: 11.

63 Ibid.; Jewell, 45.

64 Bruce Dudley, “Colonels Outhit Yankees”: 11.

65 “Ruth, Here for Derby, Exults in His Freedom,” Louisville Courier-Journal, April 30, 1936: 45.

66 Tommy Fitzgerald, “More People Fooled at 1936 Derby by Ruth Than by Bold Venture,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 19, 1948: 19.

67 David Magee and Philip Shirley, Sweet Spot: 125 Years of Baseball and the Louisville Slugger (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009), 45.

68 “Ruth Asks Hillerich to Baseball Banquet,” Louisville Courier-Journal, December 16, 1933: 10.

69 Magee and Shirley, 56-57.

70 Magee and Shirley, 57.

71 Magee and Shirley, 54.

72 Earl Ruby, “Audubon Championship,” The Foreground Column, Louisville Courier-Journal, July 15, 1936: 14. Jack Harrison, “A Scorecard That Was Worth Keeping,” Louisville Eccentric Observer, August 9, 2000: 22.

73 Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Fireside Books, 1974), 407-408.

74 “Burke Is Leader,” Louisville Courier-Journal, February 28, 1932: 33.

75 “Ruth, Here for Derby,” 47. Earl Ruby, “A Tip a Day,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 1, 1936: 27. Harrison: 22.

76 Earl Ruby, “Babe a Portsider,” Louisville Courier-Journal, April 30, 1936: 46.

77 Harrison: 22.

78 “Ross-Woods May Draw Top Crowd,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 1, 1936: 27.

79 Heggy Dent, “Ross Knocks Out Woods With Shower of Blows in the Fifth,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 2, 1936: 13.

80 Dent: 14.

81 “Ross-Woods May Draw Top Crowd”: 27.

82 Marshall Smelser, The Life That Ruth Built: A Biography (New York: Bison Books, 1993), 533-535.

83 Ulric Bell, “Favorites of Fortune Try Lucky Fling,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 3, 1936: 7.

84 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Ruth Set Autographing Mark Here,” 17. “Ruth and Gehrig Delight,” 18.

85 Tommy Fitzgerald, “More People Fooled at 1936 Derby”: 19.

86 Ibid.

87 Ibid.

88 Ibid.

89 “Dudley May Be Host to Babe Ruth,” Ruby’s Report, Louisville Courier-Journal, May 21, 1948: 45.

90 Ibid.

91 Tommy Fitzgerald, “More People Fooled at 1936 Derby,” 19. Email Interview with Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory curator and exhibits director Chris Meiman, July-August 2018.

92 Email Interview with LSMF curator Chris Meiman, August 2018.