Guilty as Charged: Buck Weaver and the 1919 World Series Fix

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

In mid-March 1921—amid delay in the criminal proceedings pending against those accused of corrupting the 1919 World Series—baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis placed the eight indicted Chicago White Sox players on the game’s ineligible list. “Baseball is not powerless to defend itself,” an impatient Landis declared. “All these players must vindicate themselves before they can be readmitted to baseball.”1 Some four-plus months later, the Not Guilty verdicts returned by the Black Sox case jury put Landis’s resolve to the test. In the defining moment of his tenure, the newly installed commissioner reacted to the trial outcome swiftly and forcefully, proclaiming:

Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game; no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ball game; no player that sits in conference with a bunch of crooked ballplayers and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are planned and discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball.2

And with that, Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, Buck Weaver, and the other acquitted Black Sox were permanently banished from Landis’s domain of the American and National Leagues and their affiliated minor leagues, consigning them to playing out their careers in outlaw exhibitions.

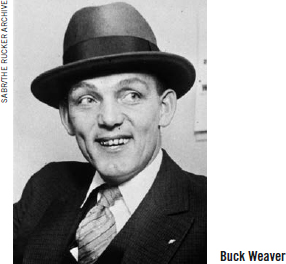

Since its promulgation, the Landis edict has been construed as confining its condemnation of third baseman Weaver to his failure to act upon pre-Series knowledge that teammates and gamblers were intent on throwing the Fall Classic. According to his champions, Weaver himself was not a fix participant. Nor did he accept any kind of payoff from those who financed the Series fix. Rather, Weaver was an honest player punished for his refusal to inform on his corrupted teammates, his permanent banishment from the game designed to serve as a warning and deterrent to players disposed to look the other way on game-fixing in future.

The purpose of this piece is to assay the legitimacy and proportion of the Weaver banishment via forensic analysis of the historical record. Unhappily for some, this exercise does not sustain the thesis that Weaver was no more than a silent confidante of Series corruption. To the contrary, the record yields persuasive evidence that Buck Weaver took an active part in the fix from start to finish, and that Weaver was among the White Sox players who threw games during the 1920 season, as well. There is no basis, therefore, to second-guess the sanction visited upon Weaver a century ago, as expulsion was a mandatory punishment for game-fixing. The deterrence rationale also justified Weaver’s banishment. To place these conclusions in context, we precede argument with a Weaver-centric review of the 1919 World Series and its aftermath.

A. BUCK WEAVER AND THE RUN-UP TO THE 1919 WORLD SERIES

By the time of the 1919 World Series, 29-year-old Buck Weaver had supplanted Home Run Baker as the American League’s premier third baseman. A rangy switch-hitter, Weaver joined the White Sox as a lineup regular in 1912 but both his hitting (.224 batting average) and fielding at shortstop (71 errors) were marginal. Over time, both skills improved, particularly after Buck was switched to third base in 1917. That season, Weaver was a reliable role-player on an American League pennant-winning club (100-54, .649) that featured three future Hall of Famers—second baseman Eddie Collins, spitballer Red Faber, and catcher Ray Schalk—as well as Cooperstown-caliber outfielder Joe Jackson and 28-game winner Eddie Cicotte. Buck then chipped in a solid World Series performance as the Sox topped the NL champion New York Giants in six games.

Batting .300, Weaver came into his own in 1918 but the season was a trying one for the Chicago White Sox. The manpower demands of World War I eviscerated the club’s roster, with Eddie Collins, Red Faber, and pitcher Jim Scott enlisting in the military, while other Sox players—including Joe Jackson, outfielder Happy Felsch, and pitcher Lefty Williams—left the club for shipbuilding work and other defense industry jobs. Despite having piloted his charges to a championship the previous season, a sixth-place finish (57-67, .460) cost Sox manager Pants Rowland his job. At the same time, a staggering drop-off in home attendance (from 684,521 in 1917 to only 195,081 in 19183) cost club owner Charles Comiskey dearly in the wallet.

Despite the financial setback, Comiskey rewarded Weaver for his stalwart performance, inking him to a handsome three-year contract in March 1919. His new pact yielded Buck $7,250 per annum and made him the second-highest paid third baseman (after Home Run Baker) in the big leagues. Meanwhile, the return of Eddie Collins, Red Faber, Joe Jackson, and the others who had left the 1918 club heralded likely restoration of the White Sox to championship form.

But the clubhouse that they were returning to was not a healthy place. Long-simmering resentment of the highly paid ($15,000), college-educated, and socially superior Collins by more hardscrabble teammates like Chick Gandil and Buck Weaver, and Comiskey’s public disdain of Joe Jackson, Happy Felsch, and other defense industry “slackers” who had avoided military service contributed to a fractious team atmosphere, with the club divided into two hostile cliques.4 Aligned with team captain Collins were Faber, Schalk, and outfielders Eddie Murphy, Nemo Leibold, and Shano Collins (no relation). In the other corner were Gandil, Cicotte, Weaver, Felsch, shortstop Swede Risberg, and sub infielder Fred McMullin, while quiet road roommates Joe Jackson and Lefty Williams mostly kept to themselves. Placed in charge of this talented but torn squad was new manager Kid Gleason, a coach on the 1917 World Series champion club.

Despite personal antagonisms, the 1919 Chicago White Sox were a powerhouse ballclub, ranking first in team batting average and leading the league in runs per game.5 Joe Jackson (.351/.422/.506), Eddie Collins (.319/.400/.405), and Nemo Leibold (.302/.404/.353) paced the batters with Buck Weaver (.296/.315/.401), Chick Gandil (.290/.325/.383), and Happy Felsch (.275/.336/.448, with 86 RBIs) also making significant contributions. Meanwhile on the mound, Eddie Cicotte (29-7, 1.82 ERA) and Lefty Williams (23-11, 2.64 ERA) hurled a combined 600+ innings, and were capably supported by undersized lefty Dickey Kerr (13-7), filling in for the frequently sidelined Red Faber (11-9).

Chicago led the AL pennant chase for most of the campaign and secured the crown with a 6-5 victory over the St. Louis Browns on September 24, Kerr notching the win in relief of ineffective starter Cicotte. Yet even before the pennant was clinched, the plot to dump the upcoming World Series against the Cincinnati Reds had been hatched.

B. THE PLAY OF BUCK WEAVER IN THE 1919 WORLD SERIES

In many respects, the fix of the 1919 World Series remains a murky affair to this day. Among the unsettled details are the number of Series fix conspiracies (there were at least two and perhaps a third); the identity of the fix financiers; how many Series games the fix actually lasted; and the timing, dollar amount, and method of payment of the corrupted White Sox players—all topics beyond the scope of this essay.

For now, suffice to say that Sox teammates Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, Lefty Williams, and Chick Gandil, as well as fix insiders Bill Burns and Billy Maharg, all later identified Weaver by name as a fix conspirator. But as in the case of Joe Jackson, Weaver’s Series stats—at least superficially—belie the charge. Playing in all eight Series contests, Weaver batted .324 (11-for-34), second only to Jackson’s .375 Series average and, like Jackson, made no errors in 27 chances. On the minus side, Weaver registered zero RBIs, failing to drive in any of the 15 teammates on base when he came to the plate.

Going in, the White Sox were heavy Series favorites6—until a last-minute surge of money on Cincinnati installed the Reds as a slight betting favorite. Most sportswriters and other baseball cognoscenti, however, remained confident of a Chicago victory. But a few, including syndicated Chicago Herald-Examiner columnist Hugh Fullerton, were disquieted by rumors that the Series outcome had been rigged.

The Series began on a sour note for Weaver and the White Sox. In the top of the first, Buck came to bat with Eddie Collins on first. Recriminations ensued when Collins was caught trying to steal. Once back in the dugout, Collins accused Weaver of ignoring the hit-and-run sign that Collins had flashed him, with Buck replying that Collins just wanted an alibi after getting thrown out.7 Three innings later, an abrupt meltdown by pitching ace Cicotte put the Sox on the road to a stunning 9-1 loss.

In Game Two, a curious one-inning loss of control by Lefty Williams provided the baserunners needed by the Reds to prevail, 4-2. A three-hit, 3-0 shutout thrown by Dickey Kerr in Game Three got the Sox in the win column, but thereafter Chicago bats went silent. With heart-of-the-lineup batters Weaver, Jackson, and Felsch unproductive, baseball’s highest-scoring club went an astonishing 26 consecutive innings without scoring a run, dropping Game Four (2-0, losing pitcher Cicotte) and Game Five (5-0, losing pitcher Williams) in the process.

With the White Sox trailing 4-1 in Game Six and on the brink of elimination, Reds left fielder Pat Duncan and shortstop Larry Kopf played Weaver’s catchable sixth-inning pop fly into a double. And with that, slumbering Chicago bats suddenly came alive. A three-run Sox rally tied the score. Gritty pitching by Kerr then kept the Reds off the board until Weaver led off the tenth inning with a legitimate double. A bouncing ball single by Chick Gandil later brought him home with the run that gave the White Sox a Series-extending 5-4 triumph. The following day finally yielded the result that Series prognosticators had been expecting all along: an easy 4-1 Chicago win behind a sterling pitching performance by Eddie Cicotte.

In Game Eight, however, the World Series comeback hopes of White Sox fans were dashed early when starter Lefty Williams failed to make it out of the first inning. With the Sox in a quick four-run hole, Weaver came to bat in the bottom of the first with runners on second and third—and took a called third strike. By the eighth inning, the Reds’ lead had grown to an insurmountable 10-1. After a four-run Sox rally reduced the margin to 10-5, Weaver came to bat in the ninth with two runners on. But his lazy fly ball to right brought the Series to within an out of its close. Joe Jackson then grounded to second, making the Cincinnati Reds the World Series winner.

Although confounded by the outcome, most sportswriters accepted the Reds’ triumph magnanimously, heaping praise on the astute managing of Cincinnati skipper Pat Moran and extolling the standout work of the club’s pitching staff. Meanwhile, complacency and overconfidence were generally cited as the basis for the Sox downfall. Few blamed the likes of Joe Jackson or Buck Weaver for the Chicago defeat. Rather, Lefty Williams (0-3, 6.61 ERA), shortstop Swede Risberg (2-for-25/.080 BA, plus four fielding errors), outfielder Nemo Leibold (1-for-18/.056 BA), and manager Kid Gleason provided more logical scapegoats.

C. THE REVELATION OF WEAVER’S ROLE IN THE SERIES FIX

Suspicion that the 1919 World Series had been fixed was the subject of several post-Series columns by Hugh Fullerton. But only a handful of fellow pressmen subscribed to fix rumors and, over time, the subject faded from public consciousness. But in the Series aftermath, both White Sox club boss Charles Comiskey and American League president Ban Johnson launched discreet inquiries into the bona fides of Sox play during the Series. And neither liked what those investigations uncovered. For the time being, however, each man sat on findings that the Series had been corrupted. Meanwhile, the 1920 baseball season started, with the AL pennant race soon devolving into a tense, three-club battle between the White Sox, New York Yankees, and Cleveland Indians.

In early September, Judge Charles A. McDonald, the presiding judge of the Cook County (Chicago) criminal courts, invited a newly-impaneled grand jury to investigate the recent report that a meaningless late-August game between the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies had been fixed by gamblers. The grand jury was also encouraged to probe Chicago’s lucrative but illegal baseball pool-selling rackets. No mention, however, was made by Judge McDonald of the previous season’s World Series.

But by the time the panel undertook a substantive look at baseball later that month, its primary focus had changed. Instigated by a private meeting between avid baseball fan McDonald and AL president Johnson, the grand jury commenced inquiry into the integrity of the 1919 World Series. And in flagrant disregard of the legal command that grand jury proceedings remain secret, panel doings were reported daily in the press.9

On September 25, 1920, it was widely reported that Comiskey had withheld the World Series checks of eight White Sox players, including that of Buck Weaver.10 Other press reports intimated that these eight players were now targeted by the grand jury for indictment on fraud-related charges.11 Two days later, the scandal dike burst with publication of a Series fix exposé in the Philadelphia North American, courtesy of local club fighter and one-time Philadelphia Phillies gofer Billy Maharg.12 Reportedly, White Sox players had thrown Games One, Two, and Eight of the 1919 World Series in return for a $100,000 payoff from gamblers.13 Within hours, wire service dispatch made the Maharg allegations known across the country.

Summoned to the office of White Sox corporation counsel Alfred S. Austrian on the morning of September 28, an unnerved Eddie Cicotte quickly broke down under questioning. According to Cicotte, the plot to rig the Series outcome in return for a payoff from gamblers was unveiled by Chick Gandil at a like-minded players-only meeting held at the Ansonia Hotel in New York City. Under pressure from Gandil, Swede Risberg, and Fred McMullin, Eddie reluctantly joined the conspiracy. Cicotte’s price was the $10,000 placed under his room pillow after a follow-up Warner Hotel meeting with fellow Sox conspirators and a pair of gamblers.14

Whisked to the Cook County Courthouse, Cicotte repeated those assertions before the grand jury that afternoon.15 Pertinent for our purposes, Cicotte identified Buck Weaver by name as one of the eight White Sox players taking part in the fix, and as attending the Warner Hotel meeting with fix gamblers.16 Immediately following Cicotte’s testimony, grand jury foreman Henry Brigham “sent for the newspaperman and in the jury’s presence announced the voting of [true] bills and the names of the players [charged].”17 Among the accused was Buck Weaver who, along with the other charged Sox players, was immediately suspended by club owner Comiskey.18

Later that day, the above exercise repeated itself with Joe Jackson. After being interrogated in the Austrian law office and thereafter confiding his culpability in the Series fix to Judge McDonald in chambers, Jackson testified before the grand jury.19 Analysis of the conflicted, often self-contradictory Jackson testimony can be found elsewhere.20 For present purposes the germane point is Jackson’s naming of Buck Weaver as a Series fix conspirator.21

Weaver strenuously denied the accusations against him, citing his solid Series batting average as “a good enough alibi.”22 But his protests were largely drowned out by deeply incriminating post-testimony statements made by Jackson to the Chicago press and by the next-day grand jury testimony of Lefty Williams.23

Like Cicotte and Jackson before him, Williams had been summoned to the Austrian office that morning. Once there, he quickly admitted his Series fix complicity. And like Cicotte and Jackson, Williams identified Chick Gandil as the fix ringleader, revealing that Chick had first importuned him outside the Ansonia Hotel. Lefty also identified Buck Weaver as a fix participant, placing Weaver at the fix meeting conducted at the Warner Hotel and at an eve-of-Game One conspirator conclave held at the Hotel Sinton in Cincinnati.24

The Hotel Sinton meeting related to a second fix proposition. This one was received from ex-major league pitcher-turned-gambler Bill Burns and former featherweight boxing champion Abe Attell, a sometimes bodyguard of New York City underworld financier Arnold Rothstein. But Williams never saw any of the $20,000 payoff that he expected from joining the Burns/Attell plot.25

Williams repeated his story before the grand jury that afternoon. But until the long-lost transcript of the Williams grand jury testimony resurfaced in 2007, it was not known to historians that Williams had expanded his account of the Warner Hotel fix meeting.26 The historical record now includes the Williams revelation that after he and the others had entertained the pitch of gamblers Sullivan and Brown, Lefty, Buck Weaver, and Happy Felsch discussed ways that Series games might be thrown during the walk back to their respective apartments. “If it became necessary to strike errors [sic] or strike out in the pinch or anything, if a critical moment arrived, strike out, boot the ball, or anything” were ways “how we would do it,” testified Williams.27

At the conclusion of the Williams testimony, the grand jury voted to indict the vaguely identified gamblers Sullivan and Brown. For purposes of clarity, readers should understand that Sullivan was Joseph “Sport” Sullivan, reputedly Boston’s biggest bookmaker. The true identity of Brown remained a mystery throughout the proceedings but Black Sox researchers now believe him to have been Nat Evans, a capable Rothstein lieutenant and junior partner in several Rothstein casino operations.

The two men likely served as emissaries of World Series fix bankroller Rothstein who funneled on the order of $80,000 through them to player ringleader Chick Gandil. Gandil then parceled out undersized portions of the payoff to corrupted Sox teammates while probably keeping the lion’s share (perhaps $35,000) of the loot for himself. This fully consummated fix is separate from the $100,000 payoff that the Burns/Attell cartel subsequently reneged on.28

With their roster decimated by player suspensions, the White Sox gamely pressed on during the season’s final week. But their outstanding final record of 96-58 (.623) was second-best to the 98-56 (.636) of the pennant-winning Cleveland Indians.29 Meanwhile, outfielder Happy Felsch became the fourth White Sox player to confess his complicity in the 1919 World Series fix. In the privacy of his home, Felsch unburdened himself to Chicago Evening American reporter Harry Reutlinger. Happy declined to name the other player conspirators but averred that everything contained in the publicly reported grand jury confession of Eddie Cicotte was the truth.30

D. THE TRIAL, ACQUITTAL, AND BANISHMENT OF THE BLACK SOX

In mid-March 1921, recently elected Cook County State’s Attorney Robert E. Crowe administratively dismissed the original indictments returned in the Black Sox case for strategic reasons. The case would be brought to trial on superseding true bills that expanded both the criminal charges and the roster of gambler defendants.31 Thereafter, Abe Attell and several other gambler defendants evaded an appearance in court by avoiding process, successfully resisting extradition, or pleading illness, while the charges against Sox infielder Fred McMullin had to be severed for trial at a later date when he did not arrive in Chicago in time for mid-June jury selection. That left Buck Weaver, six other White Sox players, and four gambler defendants in the dock when trial proceedings began.

While waiting for the Black Sox trial to commence, Commissioner Landis exercised the plenary powers granted to him by the major-league club owners when he assumed office in January. On March 24, 1921, he permanently expelled Phillies infielder Gene Paulette for suspected collusion with St. Louis gamblers in a game-fixing scheme.32 The Paulette banishment was ordered pursuant to the unfettered discretion accorded Landis to take whatever action he deemed necessary to further “the best interest of the national game of baseball.”33

After prolonged jury selection, the Black Sox criminal trial began in earnest on July 18, 1921. During those proceedings, the prosecution’s star witness was gambler defendant-turned-State’s evidence Bill Burns, who coolly recounted his part of the World Series fix over the course of three days on the witness stand. When it came to Buck Weaver, Burns identified him as one of the White Sox players in attendance at the pre-Game One fix meeting conducted at the Hotel Sinton.34 Due $40,000 after the Black Sox dumped Game Two, conspirators Chick Gandil, Eddie Cicotte, Swede Risberg, Fred McMullin, and two other Sox players whom Burns did not then recall gathered in Room 708 of the Hotel Sinton to await their payoff. But when Burns only produced $10,000—procured from cash-flush but greedy fix partner Abe Attell—Gandil angrily accused Burns of a double-cross.

Nevertheless, Chick assured him that the Black Sox would stick to the prearranged plan to lose Game Three, and Burns and Maharg bet accordingly. The hapless pair were then wiped out when Dickey Kerr pitched Chicago to an unscripted 3-0 victory.35 Later in the proceedings, Billy Maharg corroborated the Burns testimony, including the identification of Weaver as a pre-Game One fix-meeting attendee at the Hotel Sinton. Affable and seemingly guileless, Maharg was deemed a credible and effective prosecution witness by most observers.36

After a mid-trial suppression motion had been denied by the court, the prosecution also introduced in evidence the grand jury confessions of Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams.37 Same were placed before the jurors via the reading of grand jury transcript colloquies by Special Prosecutor Edward Prindiville and grand jury stenographer Walter Smith. But here, constitutional protections and courtroom rules prohibiting the admission of hearsay evidence redounded to the benefit of Weaver and the other non-confessing accused.38 Where the grand jurors had heard Buck Weaver, Chick Gandil, et alia, identified by name as Series fix participants, the trial jurors heard only the anonym Mr. Blank wherever the name Weaver, Gandil, or others appeared in the transcripts—a process that rendered parts of the confession evidence largely unintelligible.39

At the conclusion of the prosecution case, the court dismissed the charges against gambler defendants Ben and Lou Levi on grounds of evidential insufficiency. Trial judge Hugo Friend also expressed reservation about the force of the proofs against Weaver, Felsch, and gambler Carl Zork. As a prima facie case had been presented against each, the court reluctantly allowed their prosecution to continue, but reserved the right to overturn any conviction that might be returned against them by the jury. The strength of the prosecution case against the remaining defendants, however, was manifest and not the subject of legal challenge.

Apart from gambler defendant David Zelcer, neither Buck Weaver nor any other of the accused took the stand when the defense turn came.40 For the most part, defense counsel simply stood up and rested their cases. Following brief prosecution rebuttal, two days of attorney summations, and Judge Friend’s instructions on the law, the case against the Black Sox was submitted to the jury.41 A breathless two hours and 47 minutes later, Not Guilty verdicts were returned for all defendants on all charges.42 This despite the fact that the prosecution had presented an overwhelming and unrefuted case against defendants Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams, and a strong, if more circumstantial one, against Gandil, Risberg, and Zelcer.43

A raucous defendant-juror celebration ensued in the courtroom.44 After taking a group photo of smiling defendants, defense counsel, defense supporters, and trial jurors on the courthouse steps, the Black Sox and those who had acquitted them repaired to a nearby Italian restaurant.45 There, jurors expressed both disdain of star prosecution witness Bill Burns and their affection for the erstwhile defendants.46 Stretching into the early morning hours, the player-juror revelry reportedly concluded with a rousing chorus of “Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here!”47

The celebration proved short-lived. Within hours of the rendering of the jury’s verdict, Commissioner Landis promulgated his edict permanently banning the eight accused-but-acquitted White Sox players from all professional baseball affiliated with his major leagues.48

E. CIVIL LITIGATION REVELATIONS

In March 1921, Charles Comiskey officially severed all connection with the Black Sox, terminating their contracts with the club and unconditionally releasing all eight banished players. In time, four of these ballplayers instituted lawsuits against the White Sox corporation. The first was a breach-of-contract action filed by Buck Weaver which sought payment of his $7,250 salary for the 1921 season, his withheld 1919 World Series share, and other damages totaling $20,000.49 More expansive lawsuits against the White Sox were thereafter filed in Milwaukee on behalf of Happy Felsch, Joe Jackson, and Swede Risberg.50

Although the lawsuits were lodged in different court venues, it was agreed that any evidence developed during the pretrial discovery period would be admissible in all proceedings. This produced developments little noted at the time but facially dispositive of the “Weaver as innocent fix bystander” claim if deemed credible: the civil trial depositions of Bill Burns and Billy Maharg.

Interrogated under oath in Chicago on October 5, 1922, Burns repeated his familiar account of fix-related events, but with one major addition—an expanded account of his delivery of the post-Game Two player payoff at the Hotel Sinton. This time when Burns related the events, he named Buck Weaver among the seven White Sox awaiting his arrival in Room 708.51 And Weaver was named as present when the $10,000 (of the $40,000 then due) was counted out on the bed by Chick Gandil.52

When deposed in Philadelphia on December 16, 1922, Billy Maharg provided corroboration of Burns’s account. Although Maharg had not accompanied Burns to Room 708 for the fix payoff, when Burns had returned to their hotel room, the two had spoken about the delivery of the $10,000 and the players’ angry reaction to the shortchange. And Maharg averred that Burns had specifically mentioned Buck Weaver by name as being among those present when the payoff was delivered.53

F. THE CAMPAIGN TO REHABILITATE BUCK WEAVER

Of the civil lawsuits, the Joe Jackson suit was the only one litigated to a verdict. But the Black Sox Scandal was old news by the time Jackson’s case came to trial in January 1924, and little, if any, press notice was taken of the deposition revelations of Bill Burns and Billy Maharg.54 And those depositions did nothing to slow a simmering campaign to rehabilitate the image of Buck Weaver.

Although pleas and petitions for reinstatement by Weaver himself to Commissioner Landis were repeatedly rejected, Buck gained some traction pleading his cause to the press. Newfound Weaver advocates in the Fourth Estate included nationally syndicated sports columnist Westbrook Pegler, who declared that “Buck Weaver was the victim of a singularly hypocritical deal in the reform that followed the [Black Sox] exposé. … Weaver was lynched because he just happened to be standing around the corner when the posse came yelling along with a rope.”55

Sportswriter John Lardner opined that “Joe Jackson and Buck Weaver were guilty of no more than thoughtlessness, under strong provocation.”56 Arguments for Weaver’s pardon, however, were invariably premised on the notion that Weaver had only been culpable of having “guilty knowledge” of the fix. Buck had not participated in the throwing of Series games. Nor had he received any type of fix payoff presumed Weaver’s press defenders.

Endorsement of that position came from a curious quarter: Black Sox gambler defendant Abe Attell. Attell had avoided removal to Chicago via extradition proceedings that bordered on courtroom farce.57 He then escaped prosecution altogether when Cook County State’s Attorney Crowe later administratively dismissed the indictments still pending against Attell and the other fugitive accused.58“I am not telling all I know, but an injustice was done Weaver when he was barred with the other players,” Attell confided to a Minneapolis sportswriter in 1934. “I know positively that Buck refused to be a party to the deal and never accepted the money proffered to him. … I always have felt sorry for Weaver,” Attell continued. “I wrote a number of letters to Judge Landis in which I explained Weaver’s innocence, but of course the judge wouldn’t take my word for anything.”59

Attell would continue sporadic efforts to clear Weaver over the next thirty years (while cashing in on diminishing interest in the Black Sox Scandal for his own benefit). This included a factually dubious first-person scandal account published in the October 1961 issue of the cheesecake magazine Cavalier.60 Here, Attell once again absolved Weaver of fix involvement.

But publication of the Attell yarn had been preceded by an equally suspect first-person scandal exposé that kneecapped the Weaver cause: “This Is My Story of the Black Sox Series” by Arnold (Chick) Gandil as told to Mel Durslag.61 Appearing in the high-circulation weekly Sports Illustrated, the Gandil account placed Buck Weaver among the White Sox players recruited by Eddie Cicotte and Chick for the original World Series fix proposed by Sport Sullivan. “Weaver suggested we get paid [the promised $10,000 per player] in advance. Then if things got too hot, we could double cross the gambler and also take the big end of the Series cut by beating the Reds. We all agreed this was a hell of a plan.”62

Weaver was also an enthusiastic backer of the second fix proposition offered by Bill Burns. “We might as well take his money, too,” quipped Buck, “and go to hell with all of them.”63 But Gandil further maintained that the players had gotten cold feet before the Series started and never went through with the fix. Still, he accepted that in being permanently banished from baseball, the Black Sox “got what we had coming.”64

However improbable and unnoticed, the Attell article in Cavalier netted the Weaver rehab campaign an unanticipated benefactor. The piece had been ghostwritten by novelist and television screenwriter Eliot Asinof. And in short order, Asinof became Buck Weaver’s foremost champion. In his seminal 1963 scandal book Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series, Asinof portrayed Weaver as “a ferocious bulldog to the Cincinnati Reds” who had spurned overtures to join the Series conspiracy and came to be regarded as “the enemy” by fix ringleader Gandil. But “Weaver didn’t care: He was there to play ball.”65

When Eight Men Out was converted into a movie 25 years later, co-screenwriter Asinof and film director John Sayles elevated Buck Weaver to the role of the wrongfully accused hero of the drama, equipping him with fictional street urchins to whom Weaver could express his bewilderment and anguish over the poor World Series play of teammates. Toward the end of the film, Asinof and Sayles also inserted a make-believe courtroom soliloquy that allowed Weaver to proclaim his innocence regarding the Series fix.66 And lest the audience somehow mistake the film’s position on Buck, Asinof proclaimed to movie reviewers that “Weaver was a total innocent. The only thing he did wrong was not rat on his buddies. He never took a dime.”67

Release of the 8MO film in 1988 was probably the high-water mark of the Buck Weaver rehabilitation effort, its heroic portrayal shaping the lasting public perception of Weaver. Shortly thereafter came a friendly, if little-read, Weaver biography, and submission of a strenuously argued if factually selective petition for Weaver’s posthumous reinstatement crafted by Chicago attorney Louis Hegeman.68,69 Baseball commissioner Fay Vincent, however, declined to entertain the application, deeming “matters such as this are best left to historical analysis and debate.”70

As a new century unfolded, Weaver’s cause was adopted by some in the Black Sox Scandal research community, including SABR Black Sox Committee founder Gene Carney. In Carney’s view, Buck “gave his best effort in every [Series] game … and was banned nevertheless for having ‘guilty knowledge’ of the fix and failing to inform his club.”71

G. THE OPPOSING VIEWPOINT RESURFACES

Those with an unsympathetic take on Buck Weaver mostly remained silent during the campaign to rehabilitate him. But the 2007 recovery of the Lefty Williams grand jury transcript and its incriminatory addenda to the Warner Hotel meeting provided new evidence of Weaver’s culpability in the Series fix. But perhaps far more crippling to the Weaver cause was renewed examination of White Sox play during the 1920 season.

At the time that the Black Sox scandal erupted in late-September 1920, contemporaneous concern about the integrity of Sox play that season had been expressed by various observers. During the close, three-way 1920 pennant race, Sox wins and losses seemed to coincide with how their principal rivals were faring on the scoreboard, and Yankees shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh later maintained that the accused players “were monkeying around so much that year you never could be sure” if they were playing on the level.72

White Sox captain Eddie Collins had no such doubts, attributing crucial Chicago losses to Buck Weaver and Eddie Cicotte. “The last series at Boston and New York was the rawest thing I ever saw,” Collins complained in late October 1920. “If the gamblers didn’t have Weaver and Cicotte in their pockets then I don’t know anything about baseball.”73 Dickey Kerr evidently felt the same way. During an important late-season game against Boston, Weaver muffed a force-out throw from Kerr. When the inning was over, the pitcher walked over to Buck and shortstop Swede Risberg and told them, “If you’d told me you wanted to lose this game, I could of done it a lot easier.” Scuffles between antagonistic Sox player groups thereupon ensued.74

As the centenary of the 1919 World Series approached, scandal scholars returned attention to the White Sox 1920 season. In 2016, Bruce Allardice, the SABR Black Sox Committee’s in-house expert on scandal gamblers, undertook a study of the Sox campaign. Surveying contemporary press reports, Allardice discovered that virtually every uncorrupted White Sox player had expressed misgivings or worse about the integrity of their accused teammates’ play during 1920. In the end, Allardice’s scrutiny of Black Sox player field performance led him to conclude that “the Sox threw games—at a minimum three, and perhaps as many as a dozen—in 1920.”75

More recently, a deep dive into the 1920 White Sox season was taken by baseball analyst Don Zminda.76 He, too, uncovered much evidence of dishonest work by Black Sox players. His review of games involving suspect play, however, rarely focused on Weaver individually, and Zminda ultimately rendered an equivocal judgment on Buck: “Weaver’s loyalty to his crooked teammates—and his performance in the games during the 1920 season that seem most likely to have been fixed—don’t exactly put him beyond suspicion.”77

ANALYSIS REVEALS BUCK WEAVER WAS ACTIVE IN THE FIX

Buck Weaver sympathizers have much in common with those who support the cause of Shoeless Joe Jackson. Both Weaver and Jackson were outstanding ballplayers and, by all accounts, nice men. The two also shared a deep love of baseball and were at or near their playing peaks when banished from the game. As for the 1919 World Series, Weaver and Jackson superficially appeared to hit well, both posting Series batting averages over .300. And from the time of their expulsion in 1921 until their deaths in the 1950s, Weaver and Jackson doggedly insisted that they were innocent of participation in the fix of the Series.

Buck Weaver and Joe Jackson have one more thing in common: a historical record containing near overwhelming evidence of their guilt in the Black Sox affair. That said, the cases against the two are not identical. (See the Spring 2019 issue of the Baseball Research Journal for this writer’s brief for the prosecution in the Jackson case.78)

Our point of departure on Weaver is, perhaps, an unlikely one: the content of the Landis banishment edict, particularly its condemnation of players who sit in conference with crooked ballplayers and gamblers intent on fixing baseball games and who do not report it to their clubs. It is universally agreed that Landis specifically directed this so-called “guilty knowledge” clause of his edict at Buck Weaver. What is mistaken is the long-prevailing notion that the grounds for Weaver’s expulsion were necessarily confined to his guilty knowledge of the Series fix.

In law, judicial rulings—and Commissioner Landis remained a sitting federal district court judge at the time he issued his Black Sox banishment order—are often couched in the alternative. This arguendo or “even if” aspect of decisions affords the court a fallback basis for the outcome in the event that its primary grounds are found faulty or inadequate upon appellate review.

In the Black Sox case, the belief that the expulsion of Buck Weaver was premised exclusively on his guilty knowledge of the Series fix is erroneous. As reflected in his denial of a 1927 Weaver reinstatement petition, Landis clearly deemed Weaver an active participant in Series corruption.79 Among other things, Landis cited Weaver’s incrimination in the grand jury testimony of Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams, and Weaver’s making “common cause [at trial] with these three players who had implicated you” in game-throwing.80

Also cited by Landis was the trial testimony of “witness [Bill Burns] who acted as an agent between gamblers and the crooked players, arranging the fixing of the Series, and he also named you as one of the participants. Thus, there is on the record the sworn testimony of four admitted participants in the ‘fixing’ that you were implicated.”81 And finally, Landis disabused Weaver of the notion the jury’s Not Guilty verdict “exonerated you and the other defendants of game fixing.”82 As far as Landis was concerned, it did not. Viewed in this light, the “guilty knowledge” clause of the banishment edict represents no more than Landis’s fallback basis for the Weaver expulsion. First and foremost, Landis expelled Weaver as a World Series fixer.

As with Joe Jackson, Weaver supporters invariably cite his .324 Series batting average as proof-positive of his fix non-involvement. But again like Jackson, the stats argument is a malleable one, and just as easily susceptible to sinister construction.83 As for clean-up batter Jackson, most of his gaudy .375 BA/team-high six RBI statistical line was compiled after Game Five, the outermost limit of the fix in the mind of many Black Sox aficionados. Prior to that, Joe was hitless with runners on base and failed to drive in any runs.

If Jackson’s bat became dangerous toward the Series’ close, Weaver’s remained harmless throughout. Batting third in the lineup, Buck came to the plate 13 times with teammates on base—and produced zero RBIs. While he managed four singles in those at-bats (.308), the hits did little damage. As previously mentioned, Buck was next-to-useless with runners in scoring position. Here, Weaver’s batting lowlights included a fly out with Shano Collins on second in the first inning of Game Seven and grounding into a double play with two more teammates on base in the third frame, his aforementioned called third strike in Game Eight, as well as the fly to right for the second-to-last out of the Series, snuffing a last-ditch rally.

As for affirmative proof of Weaver’s active participation in the Series fix, the historical record reeks of it. Before the grand jury, Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams all specifically named Weaver as a fix conspirator. This is telling because, whatever their shortcomings, none of the three were malicious men or “had it in” for Weaver. To the contrary, all three were on friendly terms with Buck. More to the point, no evidence that Cicotte, Jackson, or Williams accused Weaver falsely has ever been uncovered—because none exists.

Weaver supporters concede Buck’s presence at the pre-Series fix meetings conducted at the Ansonia (New York), Warner (Chicago), and Sinton (Cincinnati) hotels that Cicotte and Williams told the grand jury about. The question therefore arises: If Weaver was as resolutely uninterested in joining the fix plot as Asinof, Sayles, and other champions maintain, why did Weaver attend a second fix meeting, this one with gamblers? Or a third, also with gamblers—and on the eve of Game One? Arguably, peer pressure, camaraderie, and/or curiosity may provide an excuse for Weaver’s attendance at the initial fix gathering. But after that, no. The only plausible explanation for Buck’s presence at follow-up meetings is that he was very much interested in getting a piece of the fix action.

The criminal trial produced more evidence of Weaver’s complicity as gamblers Burns and Maharg testified that Weaver was in on it. At the risk of overkill, Weaver’s participation in the fix can also be inferred from Felsch’s admission that the widely publicized grand jury testimony of Cicotte was the truth, and by the stated belief of post-Game Three fix revival gamblers Harry Redmon and Joe Pesch that seven White Sox regulars and one substitute player were fix participants.84 Doing the math here is just one more thing that puts Buck Weaver in the fix.

Decades after the fact, Chick Gandil’s Sports Illustrated reminiscences raised the number of Series fix collaborators who implicated Buck Weaver to nine—six of whom cited Weaver by name (Cicotte, Jackson, Williams, Burns, Maharg, and Gandil), three by inference (Felsch, Redmon, and Pesch). And they all accused Buck of more than just having “guilty knowledge.” These insiders portrayed Weaver as an active participant in the plot to throw the 1919 World Series.

Another Weaver talking point—the absence of evidence that he received payment for fix participation—is largely illusory, as proving a negative is always problematic.85 More instructive here is evidence that Weaver was among the Sox players who threw games during the 1920 season, with Clean Sox Eddie Collins and Dickey Kerr making specific charges of game-throwing that season against Buck. The question then arises: Would Weaver have done gamblers’ bidding in 1920 if he had not received payment for his efforts on their behalf in the previous year’s World Series? The question seemingly answers itself.

Lastly, if deemed credible, the civil case depositions of Burns and Maharg drive the final nail into the Weaver coffin. According to Burns, after the Black Sox had dumped Game Two, the corrupted players (save Joe Jackson) gathered in Room 708 of the Hotel Sinton for an expected $40,000 payoff. But Burns only delivered $10,000, a shortchange that angered the players and caused their separation from the second (Burns-Attell) World Series fix.

Burns’s placement of Weaver in attendance at that payoff gathering was corroborated by sidekick Maharg. In his deposition, Maharg distinctly remembered Burns mentioning Weaver as one of the players in attendance. With the Black Sox criminal proceedings concluded and the two in no kind of legal jeopardy, there is no apparent reason why Burns, and especially Maharg, would have lied about the incident when deposed in 1922. Needless to say, if the Burns and Maharg depositions are believed, Buck Weaver has no defense—as there can be no innocent explanation for his presence in Room 708 at the time of the fix payoff.

PERMANENT EXPULSION WAS THE APPROPRIATE SANCTION

There was ample precedent for the lifetime banishment of ballplayers engaged in game-fixing,86 and expulsion was the sanction compelled for game-fixing by the American League Constitution.87 In the Weaver case, once Commissioner Landis determined that Buck had actively participated in the plot to rig the 1919 World Series, his permanent expulsion from the game was mandatory. The Weaver banishment was further warranted under the “best interests” command of the Commissioner’s duties. As even Weaver supporters cannot dispute, the provision of the Landis edict that imposed banishment on ballplayers who “sit in conference” with those hatching game-fixing schemes had salutary deterrent effect. After the Weaver expulsion, game-fixing virtually disappeared from the American and National Leagues.88

In the final analysis, the historical evidence of Buck Weaver’s participation in the fix of the 1919 Series is as strong as it is regrettable. And if corruption of the World Series, the game’s ultimate event, would not warrant expulsion, then what would? So, to paraphrase Chick Gandil, with banishment Buck got what he had coming. In the end, much like Joe Jackson, Weaver presents a sad figure, but hardly an innocent one.

BILL LAMB spent more than 30 years as a state/county prosecutor in New Jersey, retiring in 2007. He served as editor of The Inside Game, the quarterly newsletter of the Deadball Era Committee, from 2012 to 2022, and has contributed articles to various SABR publications including the Baseball Research Journal, The National Pastime, and the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter. Bill is also the 2019 recipient of the Bob Davids Award, SABR’s highest honor. He lives with his wife Barbara in Meredith, New Hampshire, and can be contacted via wflamb12@yahoo.com.

Notes

1. As quoted in the Boston Globe, Hartford Courant, and elsewhere, March 13, 1921.

2. As reported in newspapers nationwide, August 3, 1921.

3. Robert L. Tiemann, “Major League Attendance,” Total Baseball (Kingston, NY: Total Sports Publishing, 7th ed., 2001), 75.

4. Following the early 1918 season departure of Lefty Williams and back-up catcher Byrd Lynn for defense plant work, the vocally patriotic Chisox boss sneered, “I don’t even consider them fit to play on my club.” See “Comiskey Wipes 2 Shipbuilders Off Sox Roster,” Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1918, 11. Later, Comiskey was reported as vowing to use “every ounce of my strength and the last cent I have” to keep defense plant jumpers Joe Jackson, Happy Felsch, and Williams “out of organized baseball forever.” See “Shipyard Ballplayers Will Never Get Back, Says Comiskey,” Salt Lake Telegram, September 17, 1918, 4.

5. See Fangraphs Leaderboards, 1919: https://www.fangraphs.com/leaders.aspx?pos=all&stats=bat&lg=all&qual=0&type=8&season=1919&month=0&season1=1919&ind=0&team=0%2Cts&rost=0&age=0&filter=&players=0&startdate=1919-01-01&enddate=1919-12-31&sort=20%2Cd.

6. Early Series odds ranged from 10-7 to 8-5 in White Sox favor, with comparably little money being bet on the Reds. For detailed analysis of the betting odds on the 1919 World Series, see Kevin P. Braig, “Don’t Believe the Dope: Few Saw Fix Coming,” Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, Vol. 11, No. 1 (June 2019), 20-32.

7. As recounted by Rick Huhn in Eddie Collins: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2008), 152. The original source of the incident is an article by syndicated sportswriter Joe Williams published in the New York Telegraph, July 10, 1943.

8. Johnson and McDonald were longtime acquaintances, and Johnson had previously floated McDonald’s name as a candidate for a vacant position on the National Commission, the three-man governing body prior to the anointment of US District Court Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis as baseball commissioner in November 1920. A Landis biographer places the McDonald-Johnson meeting at Edgewater Golf Club on the outskirts of Chicago. See David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, IN: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1998), 164.

9. The only justification offered for this egregious breach of black letter law was the belated pronouncement that “officials of Chief Justice McDonald’s court, desirous of giving the national game the benefit of publicity in its purging, lifted the curtain on the grand jury proceedings,” per the Associated Press wire and published nationally. See e.g., “Two White Sox Players Confess; 8 Are Indicted; Comiskey Cleans Out Team,” Baltimore Sun, September 29, 1920, 1, and “Officials Give Publicity to Purging of Game,” Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald, September 29, 1920, 1.

10. See e.g., “Jury Convinced Crooked Work Was Done by Players in League with Gamblers,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 25, 1920, 14; “More White Sox Players Involved in 1919 Scandal,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 25, 1920, 10; “Scandal in Baseball Ranks,” Washington (DC) Post, September 25, 1920, 10.

11. See e.g., “Name of Baseball ‘Fixer’ Is Known by Grand Jury,” Boston Globe, September 25, 1920, 4.

12. Maharg is identified as an assistant trainer in a 1916 Philadelphia Phillies team photo and he played an inning in the Phils outfield in the final game that season. Earlier in 1912, the athletic Maharg had been a one-game replacement at third base during a brief Detroit Tigers players strike.

13. James C. Isaminger, “Philadelphia Gambler Tells of Deal with Chicago Players to Lose Series,” Philadelphia North American, September 27, 1920, 1.

14. Per the transcript of the Cicotte statement given at the Austrian law office, September 28, 1920, and viewable online via the invaluable Black Betsy website. Readers should note, however, that the posted transcript is an abridged eight-paragraph version of the Austrian-Cicotte interview. A complete, unabridged account of the interview is not available.

15. In so doing, however, Cicotte endeavored to minimize his fix participation, presenting a significantly different picture of his own culpability as compared to the abject admissions that he had made earlier in the day at the Austrian office. For comparison and analysis of these differing Series fix confessions, see Bill Lamb, “Reluctant Go-Along or Fix Ringleader? Analysis of Eddie Cicotte’s Role in the Corruption of the 1919 World Series,” Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, Vol. 12, No. 2 (December 2020), 3-9.

16. Like much of the Black Sox record, the transcript of Eddie Cicotte’s grand jury testimony has been lost. A “Synopsis of Testimony of Edward V. Cicotte,” however, is among the scandal artifacts contained in the Black Sox collection at the Chicago History Museum. In all probability, this 24-paragraph synopsis of the Cicotte testimony was created by Assistant State’s Attorney Hartley Replogle or fellow Black Sox grand jury prosecutor Ota P. Lightfoot.

17. Per “Eight of White Sox Indicted,” Chicago Dally News, September 28, 1920, 1. The public disclosure of charges prior to the completion of the probe was highly unorthodox and ran counter to lead grand jury prosecutor Replogle’s previously stated preference that “all indictments … be returned in a bunch” when the inquiry concluded. Chicago Evening Post, September 28, 1920.

18. As reported in “Jackson and Cicotte Admit Guilt; Cleveland Almost Sure of Pennant,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 29, 1920, 1; “Comiskey Pulls Down Pennant Hopes to Steady Game’s Foundations,” Tampa Morning Herald, September 29, 1920, 7; and elsewhere.

19. The Jackson admissions in chambers were not memorialized, but testifying at the Jackson civil lawsuit against the White Sox in early 1924, Judge McDonald named Buck Weaver as one of the fix conspirators identified privately by Jackson to him. Transcript of Jackson civil trial, 552.

20. A detailed account of the Jackson grand jury testimony is provided by the writer in Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2013), 52-54, and “An Ever-Changing Story: Exposition and Analysis of Shoeless Joe Jackson’s Public Statements on the Black Sox Scandal,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Spring 2019), 38-40.

21. Transcript of Jackson grand jury testimony at 20-3 to 7.

22. As quoted in the Boston Globe and The New York Times, September 29, 1920. Weaver mistakenly gave his Series batting average as .333. He actually batted .324.

23. Among other things, Jackson complained about receiving only $5,000 of the $20,000 promised him for joining the Series fix and declared that “the eight of us did our best” to lose Game Three but were thwarted by the shutout pitching of “little Dick Kerr. … Because he won it, the gamblers double crossed us because we double crossed them,” first reported in the Chicago Daily Journal and Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1920.

24. Statement of Claude “Lefty” Williams, September 29, 1920, viewable online at www.famoustrials.com/blacksox, and elsewhere.

25. During his grand jury testimony, Williams stated that he received $10,000 from Chick Gandil the night before Game Five and that he gave half the money to Joe Jackson back at their hotel. Transcript of grand jury testimony of Claude Williams at 27-10 to 16. This money presumably emanated from the original Series fix arranged with Rothstein agents Sullivan and Brown.

26. The Williams grand jury transcript was among the scandal artifacts obtained at auction by the Chicago History Museum in December 2007. Although not publicly disclosed, the document’s source is presumed to be the successor of the law firm of White Sox corporation counsel Alfred S. Austrian.

27. Williams grand jury transcript at 29-26 to 30-7. Prior to the recovery of the Williams grand jury transcript, many scandal researchers simply supposed that the content of the Williams testimony was identical to the long-available statement that he had given in the Austrian law office.

28. The Burns/Attell group included Burns’s friend Billy Maharg and Des Moines gambler David Zelcer, with recently cashiered NY Giants first baseman Hal Chase facilitating matters. A nebulous post-Game Three fix revival effort orchestrated by St. Louis gamblers Carl Zork and Ben Franklin is yet another entry in World Series fix scenarios.

29. The excellent 95-59 (.617) record of the New York Yankees was good for no better than third place in the tight AL pennant chase of 1920. But the record-shattering 54 home runs swatted by Yanks pitcher- turned-everyday outfielder Babe Ruth that season would revolutionize the way that the game was played.

30. “I Got Mine, $5,000—Felsch,” Chicago Evening American, September 30, 1929, 1.

31. In addition to reindicting all the previously named defendants, the March 1921, superseding indictments made Midwestern tinhorns David Zelcer, Carl Zork, Benjamin Franklin, and Ben and Lou Levi answerable to the charges.

32. As reported in the Chicago Tribune, The New York Times, and newspapers nationwide, March 25, 1921.

33. See Pietrusza, Judge and Jury, 173-74.

34. As is the case with the grand jury minutes, only fragments of the Black Sox criminal trial record survive. But extensive verbatim excerpts of the Burns testimony were published in the press. See e.g., “Burns Reveals Further Facts in Series Plot,” (Indianapolis) Indiana Times, July 20, 1921, 8; “World’s Series Made to Order,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 20, 1921, 14.

35. As reported nationwide. See e.g., “Story of How Chicago Players Double- Crossed Gamblers When They Failed to Receive Bribe Money Is Revealed by Bill Burns on the Witness Stand,” Casper (Wyoming) Daily Tribune, July 21, 1921, 4; “Burns Admits on Stand to Being Stakeholder in Baseball Conspiracy,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 20, 1921, 14.

36. According to Eliot Asinof, Maharg was “an articulate witness [who] added a strong layer of testimony to the State’s already strong case.” Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series (New York: Henry Holt, 1963), 202.

37. No claim that the grand jury transcripts were inaccurate or unreliable was asserted by the defense. Rather, suppression was sought on the ground that the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand jury testimony had been induced by broken, off-the-record promises of immunity. With questioning strictly limited to events occurring in and around the grand jury room, defendants Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams testified in support of the application out of the jury’s presence. In response, former ASA Replogle and Judge McDonald countered that no such inducement had been offered. In denying the motion, trial judge Hugo Friend necessarily decided this swearing contest in favor of the prosecution witnesses.

38. Although it would be decades before the protections of the Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause would be applicable in state court prosecutions, the analogous provision in the Illinois State Constitution of 1870 shielded the non-confessing Black Sox defendants from the Cicotte/Jackson/Williams confessions.

39. As reported in newspapers across the country. See e.g., “Technicalities Galore Raised,” Grand Island (Nebraska) Daily Independent, July 26, 1921, 3; “Baseball Trial Goes by Spasms, Ogden (Utah) Standard- Examiner, July 26, 1921, 6. This editing process is known as redaction and was required by Judge Friend before the prosecution could utilize the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand jury testimony before the trial jury.

40. The defenses of Chick Gandil and Carl Zork presented proof but neither Zork nor Gandil testified.

41. A prosecution attempt to belatedly introduce the Felsch newspaper confession as rebuttal evidence was rejected by Judge Friend—the court ruling that this damning proof should have been offered during the prosecution’s case-in-chief.

42. The Associated Press reported that jurors spent more time on mechanical chores like affixing their 12 signatures to multiple separate verdict sheets than they did deliberating on the proofs. See e.g., “‘Black Sox’ Doomed,” Bellingham (Washington) Herald, August 3, 1921, 7.

43. In previous works this writer has postulated that certain of the acquittals were the product of a rare but dread courthouse phenomenon known as jury nullification. See e.g., “Jury Nullification and the Not Guilty Verdicts in the Black Sox Case,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Fall 2015), 47-56.

44. Jurors paraded around the courtroom with several of the player defendants on their shoulders, as reported in the Atlanta Constitution, The New York Times, and elsewhere, August 3, 1921.

45. Well known to Black Sox researchers, the group photo on the courthouse steps was originally published in the Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1921.

46. As reported in the Des Moines Evening Times and Los Angeles Times, August 3, 1921.

47. Per the Des Moines Evening Times and Los Angeles Herald Examiner, August 3, 1921.

48. Although occupied by his duties as a Chicago federal district court judge during the Black Sox trial, Landis had kept close watch over the proceedings via the trial transcript delivered daily to his chambers, as reported by the Chicago Evening Post, August 3, 1921. In banishing the Black Sox, Landis applied the precedent recently established by Pacific Coast League expulsion of ballplayers who had had game-fixing criminal charges dismissed by a Los Angeles court on statutory construction grounds.

49. The Weaver lawsuit was filed in the Chicago Municipal Court by attorneys Charles A. Williams and Julian C. Ryerson on October 18, 1921. Days later, the action was transferred to federal district court on diversity of citizenship grounds, the defendant White Sox having been incorporated in Wisconsin.

50. The Felsch lawsuit was instituted on February 9, 1922, while the Jackson and Risberg cases were filed on May 12, 1922. Representing all three plaintiffs was young firebrand Milwaukee attorney Raymond J. Cannon, a one-time semipro teammate of Happy Felsch.

51. Of the Black Sox, only Joe Jackson was absent from the room.

52. Deposition of Bill Burns as admitted in evidence at the early 1924 trial of the Jackson civil lawsuit. See Jackson trial transcript at 695-98.

53. Deposition of Billy Maharg. See Jackson trial transcript at 730-34.

54. A $16,000+ civil jury award in Jackson’s favor was promptly vacated by the trial judge who ruled that the judgment was based on perjured testimony. The suit was later quietly settled out of court for a pittance. A similar outcome attended the other actions. For more on the Black Sox civil litigation, see again William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 149-98.

55. Westbrook Pegler, “Nobody’s Business: Great Chance Reporters Muffed,” Omaha World-Herald, November 13, 1932, 25.

56. John Lardner, “Hall of Fame Contenders Include Baseball Outlaws,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, January 22, 1938, 10.

57. Among other things, Attell defense counsel William J. Fallon shamelessly argued that there were actually two Abe Attells and that prosecutors were trying to extradite the wrong one. Perhaps more effectively, Fallon also bribed the prosecution’s principal extradition witness (Chisox groupie Sam Pass) into testifying that the Abe Attell in court was not the gambler with whom he had placed high-stakes World Series wagers.

58. The outstanding indictments against defendants Attell, Fred McMullin, Sport Sullivan, Hal Chase, and Rachael Brown were dismissed by SA Crowe only days after the Not Guilty verdicts had been returned in court.

59. George A. Barton, “Sportsgraphs: Abe Attell Absolves Buck Weaver,” Minneapolis Tribune, April 27, 1934, 30.

60. Abe Attell, “The Truth Behind the World Series Fix,” Cavalier, October 1961, 9-13, 89-90.

61. Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956.

62. Gandil, Sports Illustrated, above.

63. Gandil, Sports Illustrated, above.

64. Gandil, Sports Illustrated, above.

65. Asinof, Eight Men Out, 63.

66. In previous writings, this writer has dissected 8MO’s historically unreliable treatment of the Black Sox saga, with particular scorn reserved for the fabrications of the movie version. See e.g., “Based on a True Story: Eliot Asinof, John Sayles, and the Fictionalization of the Black Sox Scandal,” The Inside Game, Vol. XIX, No. 3 (June 2019), 35-43, and the 8MO historical errata catalogue appended to the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee’s online Eight Myths Out project. See also, Bill Lamb, “1919: A Loss of Innocence and a Few Key Facts,” Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, Vol. 13, No. 2 (December 2021), 11-16.

67. As quoted in Ed Sherman, “Chicago Strikes Out,” Chicago Tribune, August 21, 1988, 288.

68. Irving M. Stein, The Ginger Kid: The Buck Weaver Story (Dubuque, IA: Brown & Benchmark, 1993).

69. Commentary on the Hegeman petition is provided in “Amnesty for Black Sox Third Baseman?” Wall Street Journal, January 17, 1992.

70. Same as above, quoting a December 12, 1991, letter from the commissioner’s office to Hegeman.

71. Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2006), 209.

72. As quoted by Donald Honig in The Man in the Dugout: Fifteen Big League Managers Speak Their Minds (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977), 216.

73. Frank O. Klein, “Collins Charges 1920 Games ‘Fixed,’” Collyer’s Eye, October 30, 1920, 5.

74. As related in Kuhn, Eddie Collins, 172. The incident was originally revealed in a 1924 article published in Baseball Magazine.

75. Bruce S. Allardice, “‘Playing Rotten, It Ain’t That Hard to Do’: How the Black Sox Threw the 1920 Pennant,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Spring 2016). The article title quotes Happy Felsch.

76. Don Zminda, Double Plays and Double Crosses: The Black Sox and Baseball in 1920 (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021).

77. Zminda, Double Plays and Double Crosses, 270.

78. See again, Lamb, “An Ever-Changing Story.”

79. The Landis ruling is re-produced verbatim by Daniel E. Ginsburg in The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1995), 148.

80. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In, 148.

81. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In, 148. Billy Maharg, a fifth witness directly implicating Weaver in the Series fix, went unmentioned by Landis.

82. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In, 148.

83. Analysis of Joe Jackson’s World Series stats appears in Lamb, “An Ever-Changing Story,” 45.

84. According to the grand jury testimony of Redmon and St. Louis Browns second baseman Joe Gedeon (a personal friend of Swede Risberg) the fix-revival meeting was conducted at the Sherman Hotel in Chicago and chaired by subsequently indicted St. Louis gamblers Carl Zork and Ben Franklin. The meeting’s intelligence that seven White Sox regulars and one substitute player were in on the fix was provided by the Levi brothers, also among those indicted.

85. This writer entirely discounts the putative, double-hearsay grand jury testimony attributed to Dr. Raymond Prettyman, the Weaver family dentist. Same concerned a package of cash supposedly delivered to the Weaver home by Fred McMullin. Both Weaver and McMullin denied the allegation, and it is unclear if Prettyman ever made it in the first place.

86. Expulsion of players engaged in game-fixing dated back to 1865. See John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 127-29. See also, Thorn, “Our Game: Baseball’s Bans and Blacklist,” February 8, 2016.

87. Adopted on February 16, 1910, the American League Constitution mandated the expulsion of any franchise that failed to terminate a player who had conspired to throw a league game.

88. Landis’s swift expulsions of Phil Douglas (1922), Jimmy O’Connell and Cozy Dolan (1924) provided the coda on game-fixing in the majors.