Sweet! 16-Year-Old Players in Major League History

This article was written by Chuck Hildebrandt

This article was published in Spring 2019 Baseball Research Journal

On June 10, 1944, during the ninth inning of a 13-0 blowout, an event occurred that is known to many fans with at least a passing knowledge of baseball history: Joe Nuxhall, at a mere 15 years and 316 days of age, made his way into an actual regular-season major league game, becoming the youngest player to ever do so.

On June 10, 1944, during the ninth inning of a 13-0 blowout, an event occurred that is known to many fans with at least a passing knowledge of baseball history: Joe Nuxhall, at a mere 15 years and 316 days of age, made his way into an actual regular-season major league game, becoming the youngest player to ever do so.

This event did not occur out of left field (as it were). Joe Nuxhall was already well-known before his big-league debut. It was widely reported earlier that year that the Cincinnati Red had signed the 6-foot-3, 195-pound ninth-grader to a major league contract.1 He’d thrown two no-hitters and two one-hitters in his “knothole league” the previous year.2 Joe’s father had himself played semipro ball, and had been training his son to be a pitcher since Joe was a little kid.3 Joe sat on the Reds’ bench that Opening Day, and it was anticipated that he would see game action at some point that season.4, 5 When Joe was finally called up to the active roster on June 8 — after his junior high school graduation, of course — there was a feature story in which he was quoted, “Would I like to get into a big-league game? What do you think I’ve been waiting for all these months?”6, 7

Of course, it’s also well known that Joe’s debut performance fell far short of the hype. Pitching against the St. Louis Cardinals, after retiring two of the first three hitters he faced, he fell apart in a manner one might expect of a junior high student: wild pitch, walk, single, walk, walk, walk, single. Five runs later, he was yanked from the game.8 Five days later, he was on his way to the Birmingham Barons farm club, where he essentially replicated his Reds debut performance.

Today it seems absurd to think it was a good idea for a boy — technically still a minor — to be allowed to compete alongside full-grown men. And yet, although Joe was a once-in-history fluke player as a 15-year-old, there have been several times in the history of professional baseball when teams allowed 16-year-olds (themselves not much closer to physical maturity9) to make that same leap onto a major-league roster. But that’s what happened on fifteen separate occasions between 1872 and 1956.10

In this article, we will explore three aspects of the phenomenon of the 16-year-old major-leaguer:

- Who were the fifteen boys who make up this exclusive club?

- How did it come to pass that 16-year-olds were even allowed to play major-league ball in the first place?

- Is it possible that a 16-year-old could ever again play in the major leagues?

1. The Fifteen 16-Year-Old Major Leaguers

Position: Shortstop, Second Base

Born: November 26, 1855

Debut: April 20, 1872

Team: Nationals of Washington (National Association)

Age: 16 years, 146 days

| G | PA | R | H | AVG | OBP | SLG | wRC+ | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 41 | 6 | 11 | .268 | .268 | .293 | 56 | -0.5 |

The first 16-year-old player in major league history stepped onto the field for the first-ever game the National Association version of the Nationals played, and his stint at baseball’s then-highest level ended after his ninth game on May 25.13 Little is known about how Jacob made his way onto the team. The newspapers around the District of Columbia saw fit only to note his appearances in box scores, not his origin story. Given the nascence of organized professional baseball, the presence of a school-aged boy in a top professional game likely seemed unremarkable. Jacob acquitted himself nicely enough: 11 hits, including a double, in 41 at bats for a .268 batting average. He even managed a base hit off eventual two-time 50-game winner and future Hall of Famer Al Spalding. Nevertheless, Jacob’s entire career spanned those nine games for the Nationals, who themselves disbanded after eleven games in total, all losses. (This being the era of “erratic schedule and procedures,” they were not the only team to close shop before a full slate of fixtures could be played.14) Jacob Doyle passed away in 1941 at the ripe old age of 85.

The first 16-year-old player in major league history stepped onto the field for the first-ever game the National Association version of the Nationals played, and his stint at baseball’s then-highest level ended after his ninth game on May 25.13 Little is known about how Jacob made his way onto the team. The newspapers around the District of Columbia saw fit only to note his appearances in box scores, not his origin story. Given the nascence of organized professional baseball, the presence of a school-aged boy in a top professional game likely seemed unremarkable. Jacob acquitted himself nicely enough: 11 hits, including a double, in 41 at bats for a .268 batting average. He even managed a base hit off eventual two-time 50-game winner and future Hall of Famer Al Spalding. Nevertheless, Jacob’s entire career spanned those nine games for the Nationals, who themselves disbanded after eleven games in total, all losses. (This being the era of “erratic schedule and procedures,” they were not the only team to close shop before a full slate of fixtures could be played.14) Jacob Doyle passed away in 1941 at the ripe old age of 85.

Position: Pitcher

Born: February 25, 1856

Debut: May 2, 1872

Team: Atlantics of Brooklyn (National Association)

Age: 16 years, 67 days

| G | GS | W | L | ERA | IP | WHIP | ERA- | bWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | 37 | 9 | 28 | 5.06 | 336 | 1.73 | 120 | 0.3 |

Unlike his predecessor above, this 16-year-old actually logged a full season as the sole pitcher for the Atlantics, hurling all 336 innings of the team’s 37 games and shouldering their entire 9–28 record. Alternately referred to in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as both “Britt”17 and “Brett”18 — sometimes in the same story19 — there’s no mention of how this particular 16-year-old happened to land with the Atlantics in the first place. The team must have had high hopes for Jim, though, particularly after some of the thrashings he administered to amateur teams in exhibition play.20,21,22 However, once the season switch flipped to “regular” mode, the effectiveness of the team, and of Jim, waned. The Atlantics were one of a handful of clubs to use a single pitcher the entire season, and it was noted of the club that “[having] no change pitcher, when Jim failed to be effective[,] their strong point was at an end.”23 Remarkably, Jim hung on with the Atlantics for the 1873 campaign as well, during which he hurled another 480⅔ innings and compiled a 17-36 record. He left the Atlantics after his age 17 season and played several more seasons for lesser Brooklyn-based clubs before moving to the West Coast.24 Jim Britt passed away at age 67 in 1923.

Unlike his predecessor above, this 16-year-old actually logged a full season as the sole pitcher for the Atlantics, hurling all 336 innings of the team’s 37 games and shouldering their entire 9–28 record. Alternately referred to in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as both “Britt”17 and “Brett”18 — sometimes in the same story19 — there’s no mention of how this particular 16-year-old happened to land with the Atlantics in the first place. The team must have had high hopes for Jim, though, particularly after some of the thrashings he administered to amateur teams in exhibition play.20,21,22 However, once the season switch flipped to “regular” mode, the effectiveness of the team, and of Jim, waned. The Atlantics were one of a handful of clubs to use a single pitcher the entire season, and it was noted of the club that “[having] no change pitcher, when Jim failed to be effective[,] their strong point was at an end.”23 Remarkably, Jim hung on with the Atlantics for the 1873 campaign as well, during which he hurled another 480⅔ innings and compiled a 17-36 record. He left the Atlantics after his age 17 season and played several more seasons for lesser Brooklyn-based clubs before moving to the West Coast.24 Jim Britt passed away at age 67 in 1923.

Position: Pitcher

Born: March 30, 1860

Debut: October 4, 1876

Team: Louisville Grays (National League)

Age: 16 years, 188 days

| G | GS | W | L | ERA | IP | WHIP | ERA- | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.50 | 4 | 1.50 | 178 | 0.0 |

Frank holds the distinction of being the first 16-year-old “one-and-done” player, but he would not have appeared at all were it not for a grisly injury-cum-cruel insult suffered by the Grays’ starting pitcher, Jim Devlin, during the team’s penultimate game of the season against the Hartford Blues. Devlin had reached first base in the fourth inning on a muffed grounder, and while taking second on a high throw to that bag, “he slid just before reaching it, his foot caught in the large iron ring holding the base-bag down, wrenching and twisting his foot severely.” Devlin knocked the base bag several feet away with his slide and was lying on his back in agonizing pain when Blues second baseman Jack Burdock came back with the errantly thrown ball and tagged Devlin, who was called out by umpire Dan Devinney to complete the insult. Devlin was carted off the field on the shoulders of two teammates but, being the only pitcher on the roster, bound up his ankle and pitched the fifth. He then thought the better of it and insisted on coming out, and so Frank, a pitcher with a local amateur team, was conscripted to finish the match. He pitched “creditably” enough, yielding only four runs in the final four innings on five hits despite eight errors committed behind him.25 Frank promptly disappeared into local amateur ball, playing into the early 1880s before becoming a local collector and traveling salesman.26 Frank Pearce died in 1926 at the age of 66.

Position: Outfielder, Shortstop

Born: December 13, 1860

Debut: July 17, 1877

Team: St. Louis Brown Stockings (National League)

Age: 16 years, 216 days

| G | PA | R | H | AVG | OBP | SLG | wRC+ | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 18 | 0 | 5 | .278 | .278 | .333 | 101 | 0.0 |

Leonidas is among the more interesting 16-year-olds who played at the top level of the game. Ostentatiously christened Leonidas Pyrrhus Funkhouser — his father was a leading businessman in St. Louis and a member of the Sons of the American Revolution27 — Leonidas had already attended Princeton University before joining the St. Louis ballclub during his summer vacation. As his family was well-established in St. Louis, given the prevailing social taboo against gentlemen engaging in roughneck activities such as “base ball,” perhaps Leonidas chose “Lee” as an alias to spare his family name embarrassment. While the circumstances under which he came to join the “Brown Sox” are a mystery, he appeared in four league games and fared nicely with a 5-for-18 performance, including a double, although his fielding left something to be desired (four errors in 11 chances at four different positions). He graduated from Princeton the following June and made his way to Omaha.28 Now reestablished as a Funkhouser, Leonidas was an up-the-order hitting outfielder and first baseman with that city’s Union Pacifics club in 1882, on which his brother Mettelus also appeared, but he would never again reach the major leagues.29, 30, 31 Leonidas moved on to Lincoln, Nebraska, where by 1902 he held officer-level positions with several companies simultaneously.32 Funkhouser/Lee died in 1912 en route from Florida to Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, for a summer retreat.33

Position: Third Base

Born: April 16, 1867

Debut: June 12, 1883

Team: Philadelphia Quakers (National League)

Age: 16 years, 57 days

| G | PA | R | H | AVG | OBP | SLG | wRC+ | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | .000 | .000 | .000 | -48 | -0.1 |

Piggy was the youngest player in big-league history for more than six decades, arriving just 57 days after his 16th birthday. He was also the first 16-year-old player to emerge from his maiden appearance to enjoy a fairly lengthy career, whereas Doyle, Pearce, and “Lee” were all out of the game before they turned 17, and Britt made it through just one more season. After a hiatus following his sole teenage appearance, Piggy re-entered the majors at age 22, then again at 24. He was a bench player until achieving nearly full-time status with the 1894 Washington Senators, playing mainly second base and slashing a respectable .303/.446/.375, including 80 walks — good for tenth in the league. He then faded into minor league obscurity for the next 12 seasons, retiring for good in 1906 after his age 39 season. In his very first big-league appearance back in 1883, though, Piggy — referred to as a “handball expert”34 — was tried out at third base, and although he did ring up two assists there, he also went 0-for-5, striking out twice, and then slipped out of pro ball until popping up with the Johnstown and Shamokin clubs in the Pennsylvania minors in 1887 to begin his second act in the game. As did so many in his day, Piggy Ward came to a rough end: he fell off a telephone pole in Altoona, Pennsylvania, in 1909 and died three years later after suffering paresis resulting from his injuries.35

Position: Pitcher

Born: November 10, 1873

Debut: May 8, 1890

Team: Cleveland Infants (Players League)

Age: 16 years, 179 days

| G | GS | W | L | ERA | IP | WHIP | ERA- | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 20 | 11 | 9 | 4.12 | 183.2 | 1.73 | 101 | 1.5 |

Despite that he was out of the bigs by 23, Willie still fashioned the best career of any major-leaguer who debuted as a 16-year-old: 14.6 fWAR, split between his pitching and hitting. Invited to try out for Cleveland’s Players League club during 1890 spring training, Willie made his debut for the coincidentally nicknamed Infants on May 8 against the Buffalo Bisons.36 He made an immediate impact due to his appearance (“he is like the little girl’s definition of a sugar plum, ‘round and rosy and sweet all over’”), stuff (“throws barrel-hoops and corkscrews at the plate … with a swift, straight ball that is as full of starch as though it had just come out of a laundry”), and performance (struck out ten batters while going 1-for-4 with a walk at the plate in a 14-5 victory).37 Willie delivered an impressively average season for a high-school-age boy. Once the Players League folded after season’s end, Willie, who’d been playing without a contract anyway, moved on to King Kelly’s Cincinnati “Killers” club of the American Association, then was sold to the St. Louis Browns early that next season.38 He eventually pitched in the National League with Cincinnati, Chicago, and Philadelphia until his final season in 1895 at age 22. He broke his pitching hand the following year, spoiling any chance for a return to the bigs, although he continued pitching in the minors and in top Chicago amateur leagues for more than a decade afterward.39, 40 Willie McGill eventually became head baseball coach at Northwestern University before moving to Indianapolis, where he died in 1944 at age 70.41

Position: Catcher

Born: August 15, 1875

Debut: June 6, 1892

Team: Baltimore Orioles (National League)

Age: 6 years, 296 days

| G | PA | R | H | AVG | OBP | SLG | wRC+ | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | .000 | .000 | .000 | -77 | 0.0 |

A good deal of mystery surrounds the saga of Tom Hess. Listed on Baseball-Reference as having started his minor-league career in 1890 with Albany at the age of 14,42 Hess was another 16-year-old one-gamer, playing catcher for the Orioles in a 23-1 laugher over the Chicago Colts. Nothing is known about how Hess ended up on the Orioles in the first place — only that he entered the game in the fifth inning for the O’s that June day and exited in the seventh after getting busted in the kneecap with a ball. Despite the pummeling the Baltimores laid on the Chicagos, Hess did nothing at the plate, making out both times.43 Hess was released by the Orioles about a week later and returned to Albany to finish out the season for the Senators there.

A good deal of mystery surrounds the saga of Tom Hess. Listed on Baseball-Reference as having started his minor-league career in 1890 with Albany at the age of 14,42 Hess was another 16-year-old one-gamer, playing catcher for the Orioles in a 23-1 laugher over the Chicago Colts. Nothing is known about how Hess ended up on the Orioles in the first place — only that he entered the game in the fifth inning for the O’s that June day and exited in the seventh after getting busted in the kneecap with a ball. Despite the pummeling the Baltimores laid on the Chicagos, Hess did nothing at the plate, making out both times.43 Hess was released by the Orioles about a week later and returned to Albany to finish out the season for the Senators there.

However, there is some dispute as to whether Tom Hess was a 16-year-old major leaguer at all, as well as whether the player in question was even Tom Hess in the first place. David Nemec’s book, The Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball, maintains that the player for the Orioles that game was a man of unknown provenance named Jack Hess, and that Tom Hess was a career minor leaguer who did not pass through Baltimore at all. As evidence, Nemec cites gaps in Tom’s minor league record between 1895 and 1899.44 However, Baseball-Reference shows Tom as having played minor league ball each season from 1890 through 1909, including A-level minor league ball in 1891; while Jack’s record is complete from 1890 to 1897, without gaps, including playing B-level minor league ball in 1892. Given this, and the lack of conclusive evidence contradicting Baseball-Reference’s record, we’ve included Tom Hess here. He passed away in 1945, aged 70.

Position: Pitcher

Born: April 2, 1881

Debut: September 11, 1897

Team: Washington Senators (National League)

Age: 16 years, 162 days

| G | GS | W | L | ERA | IP | WHIP | ERA- | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.2 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.0 |

Joe was one of the few 16-year-olds with a big-league career spanning several years, with an unusual twist: he debuted for the Senior Circuit Senators as a one-and-done teenage pitcher, then returned to the Junior Circuit Senators as a 21-year-old outfielder. There he remained for six seasons and 215 games, with two mop-up mound appearances. In that teenage debut game in 1897, with his squad being crushed by the Cincinnati Reds, 14-5, after seven innings, Senators manager Tom Brown called on Joe to take one for the team. The 5’9”, 150-pound pitcher was brought in along with 5-foot-7, 168-pound catcher Tom Leahy to serve as his “mustang pony battery”45 and finish the first game of a doubleheader. Joe, a local “District lad,” was “nervous” and ended up walking three and throwing a wild pitch while yielding another five runs in the final two frames, a number the Senators matched in their half of the ninth before finally falling, 19-10. He also went 0-for-2 at the plate.46 (It should be noted that this account from the next day’s Washington Times stands at odds with the record of Joe’s one-game performance as reflected in Retrosheet: ⅔ IP; no runs, hits, walks or strikeouts; one wild pitch; 0-for-1 at the plate. For consistency, it is this record reflected above.47) From there, Joe next showed up on the Newport News club of the Virginia League in 1900, then in Raleigh and New Orleans during the 1901 season before making his way up to the American League Senators that season. He bounced up and down between the bigs and the bushes before settling into the minors from 1910 through his retirement in 1917. When Joe Stanley died in Detroit in 1967, he had been one of the last living nineteenth century players.48

Joe was one of the few 16-year-olds with a big-league career spanning several years, with an unusual twist: he debuted for the Senior Circuit Senators as a one-and-done teenage pitcher, then returned to the Junior Circuit Senators as a 21-year-old outfielder. There he remained for six seasons and 215 games, with two mop-up mound appearances. In that teenage debut game in 1897, with his squad being crushed by the Cincinnati Reds, 14-5, after seven innings, Senators manager Tom Brown called on Joe to take one for the team. The 5’9”, 150-pound pitcher was brought in along with 5-foot-7, 168-pound catcher Tom Leahy to serve as his “mustang pony battery”45 and finish the first game of a doubleheader. Joe, a local “District lad,” was “nervous” and ended up walking three and throwing a wild pitch while yielding another five runs in the final two frames, a number the Senators matched in their half of the ninth before finally falling, 19-10. He also went 0-for-2 at the plate.46 (It should be noted that this account from the next day’s Washington Times stands at odds with the record of Joe’s one-game performance as reflected in Retrosheet: ⅔ IP; no runs, hits, walks or strikeouts; one wild pitch; 0-for-1 at the plate. For consistency, it is this record reflected above.47) From there, Joe next showed up on the Newport News club of the Virginia League in 1900, then in Raleigh and New Orleans during the 1901 season before making his way up to the American League Senators that season. He bounced up and down between the bigs and the bushes before settling into the minors from 1910 through his retirement in 1917. When Joe Stanley died in Detroit in 1967, he had been one of the last living nineteenth century players.48

Position: Catcher

Born: October 18, 1892

Debut: August 15, 1909

Team: St. Louis Cardinals (National League)

Age: 16 years, 301 days

| G | PA | R | H | AVG | OBP | SLG | wRC+ | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | .000 | .000 | .000 | -94 | 0.0 |

The first 16-year-old player of baseball’s modern era, “Coonie” (or more likely “Connie”49, 50) capped a momentous year of baseball by playing in his one and only big-league game for his hometown Cardinals. Coonie started the year on a St. Louis “trolley league” team that had traveled to Springfield, Missouri, for an exhibition series against the Class C Midgets of the Western Association.51 The Midgets liked him well enough to try him out as their catcher before quickly releasing him.52, 53 He moved on to the Guthrie and Muskogee clubs in the same league during May before making his way back to Springfield by July, where he stuck into August.54, 55, 56 Then, on the 15th of that month, Coonie found himself substituting for starting catcher Jack Bliss in the first game of a late season doubleheader in St. Louis as the Redbirds were winding up a stretch of 14 games in 13 days before hitting the road. He was less than impressive during the game: the Brooklyn paper mentioned that “the Dodgers ran wild on the sacks,” and that Coonie would “need a lot of seasoning.”57 He wouldn’t get it: Coonie was one-and-done as far as the majors were concerned. There’s no record of where he went after his sip of coffee, and he was out of pro ball entirely by age 18. Coonie Blank died in his hometown in 1961.

Position: Pitcher

Born: September 16, 1926

Debut: August 18, 1943

Team: Philadelphia Phillies (National League)

Age: 16 years, 336 days

| G | GS | W | L | ERA | IP | WHIP | ERA- | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16.20 | 3.1 | 3.30 | 385 | -0.1 |

The first 16-year-old major-leaguer of the World War II era, Roger Hornsby McKee is also the first whose rise to the majors was well-chronicled in contemporaneous newspaper reports. The previous year he’d earned several mentions in the nearby Asheville, North Carolina, daily paper as a star pitcher for his hometown Shelby American Legion Juniors team. Roger was 9-1, averaged 14 strikeouts per game, and batted .500 in 1943.59 He was signed August 12 by the Phillies as a “17”-year old, his smiling face appearing in papers across the country via AP Wirephoto.60 Roger made his debut in Philly less than a week later, relieving Jack Kraus in the seventh inning against the Cardinals, who were already down 5-0. Roger pitched well despite an especially tough assignment: the first four batters he faced were All-Stars Harry “the Hat” Walker (bunt single), Stan Musial (base on balls), Walker Cooper (5-4-3 double play), and Whitey Kurowski (fly out to right to retire the side without a run). He finished the game, giving up only one run in three innings. He pitched once more as a 16-year-old, four days later, yielding an ignominious result: three hits, three walks and five runs, all earned, in ⅓ inning. Roger pitched two more games that season after turning seventeen, and one final big-league game as an 18-year-old in late 1944 after a season at Class B Wilmington before shipping out to the Navy in 1945.61 After the war, Roger sailed into a long minor league career as an outfielder, retiring at age 30 before returning home to Shelby to become a postal carrier. Roger McKee passed away in 2014.62

The first 16-year-old major-leaguer of the World War II era, Roger Hornsby McKee is also the first whose rise to the majors was well-chronicled in contemporaneous newspaper reports. The previous year he’d earned several mentions in the nearby Asheville, North Carolina, daily paper as a star pitcher for his hometown Shelby American Legion Juniors team. Roger was 9-1, averaged 14 strikeouts per game, and batted .500 in 1943.59 He was signed August 12 by the Phillies as a “17”-year old, his smiling face appearing in papers across the country via AP Wirephoto.60 Roger made his debut in Philly less than a week later, relieving Jack Kraus in the seventh inning against the Cardinals, who were already down 5-0. Roger pitched well despite an especially tough assignment: the first four batters he faced were All-Stars Harry “the Hat” Walker (bunt single), Stan Musial (base on balls), Walker Cooper (5-4-3 double play), and Whitey Kurowski (fly out to right to retire the side without a run). He finished the game, giving up only one run in three innings. He pitched once more as a 16-year-old, four days later, yielding an ignominious result: three hits, three walks and five runs, all earned, in ⅓ inning. Roger pitched two more games that season after turning seventeen, and one final big-league game as an 18-year-old in late 1944 after a season at Class B Wilmington before shipping out to the Navy in 1945.61 After the war, Roger sailed into a long minor league career as an outfielder, retiring at age 30 before returning home to Shelby to become a postal carrier. Roger McKee passed away in 2014.62

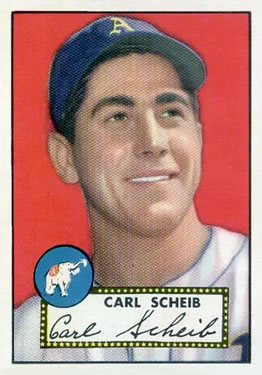

Position: Pitcher

Born: January 1, 1927

Debut: September 6, 1943

Team: Philadelphia Athletics (American League)

Age: 16 years, 248 days

| G | GS | W | L | ERA | IP | WHIP | ERA- | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.34 | 18.2 | 1.45 | 131 | -0.4 |

Carl, the first 16-year-old (and still youngest player) in American League history, took a slightly different path from the 16-year-olds before him. He racked up notices in newspapers around his hometown of Gratz, Pennsylvania, about his stellar pitching and hitting during 1941 and 1942. Though still a 15-year-old in August 1942, he received a tryout with Connie Mack’s A’s. Carl impressed the old man greatly. “There’s only one thing against the boy and that’s his age,” Mack was quoted as saying, “However, bring him down next year as soon as school closes [and we’ll] take care of him. In the meantime, don’t let Carl pitch too much.”63 The following year, Carl spent the entire season with the Athletics as a batting practice pitcher, a job for which he’d quit high school.64 He also pitched for the Athletics in several off-day exhibition games.65 Eventually, with the Pittsburgh Pirates and “another major league club” reportedly interested in Carl, Mack signed him to a big-league contract and brought him into his first game in relief against the New York Yankees.66 Carl was greeted roughly by hitter Nick Etten’s triple, after which Joe Gordon plated Etten with a groundout. Nevertheless, Carl “did O.K.”67 Unlike most 16-year-old rookies, Carl stuck around the majors for a while, pitching with the A’s until age 27, passing through the Cardinals that same year, and winding up his career in the Pacific Coast and Texas Leagues before retiring at age 30. Carl Scheib passed away in San Antonio in 2018 at the age of 91.

Carl, the first 16-year-old (and still youngest player) in American League history, took a slightly different path from the 16-year-olds before him. He racked up notices in newspapers around his hometown of Gratz, Pennsylvania, about his stellar pitching and hitting during 1941 and 1942. Though still a 15-year-old in August 1942, he received a tryout with Connie Mack’s A’s. Carl impressed the old man greatly. “There’s only one thing against the boy and that’s his age,” Mack was quoted as saying, “However, bring him down next year as soon as school closes [and we’ll] take care of him. In the meantime, don’t let Carl pitch too much.”63 The following year, Carl spent the entire season with the Athletics as a batting practice pitcher, a job for which he’d quit high school.64 He also pitched for the Athletics in several off-day exhibition games.65 Eventually, with the Pittsburgh Pirates and “another major league club” reportedly interested in Carl, Mack signed him to a big-league contract and brought him into his first game in relief against the New York Yankees.66 Carl was greeted roughly by hitter Nick Etten’s triple, after which Joe Gordon plated Etten with a groundout. Nevertheless, Carl “did O.K.”67 Unlike most 16-year-old rookies, Carl stuck around the majors for a while, pitching with the A’s until age 27, passing through the Cardinals that same year, and winding up his career in the Pacific Coast and Texas Leagues before retiring at age 30. Carl Scheib passed away in San Antonio in 2018 at the age of 91.

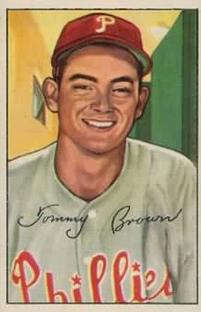

Position: Shortstop

Born: December 6, 1927

Debut: August 3, 1944

Team: Brooklyn Dodgers (National League)

Age: 16 years, 241 days

| G | PA | R | H | AVG | OBP | SLG | wRC+ | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46 | 160 | 17 | 24 | .164 | .208 | .192 | 11 | -2.0 |

Tommy Brown holds two distinctions: he is the youngest 16-year-old player of the twentieth century, and he is the only starting position player on this list. He appeared in more games as a 16-year-old than any other player in major league history. The Dodgers did not bring Tommy to Ebbets Field as a novelty — they brought him there to play. Signed by the club after an open tryout, he was assigned to their Class B Newport News farm club and showed some serious skills there. Tommy was leading the Piedmont League in triples, as well as socking 21 doubles and even a towering home run over a right-center field fence, practically forcing the then last-place Brooklyns to purchase his contract on July 28.68, 69, 70 So popular was Tommy in Newport News that they held a “day” in his honor before he left, and the local paper continued to report on his performance while he was with the Dodgers.71 But Tommy wasn’t a big deal just in Virginia — New York papers wrote feature pieces heralding the arrival of the Dodgers’ new boy wonder.72 Unique among 16-year-olds, Tommy was immediately installed by his team as their starting shortstop. He had a promising start, clouting a double and scoring a run in his debut, and was batting .278 after his first six games. Alas, his youthful inexperience eventually caught up with him: his batting average plummeted below .200 for good by Labor Day, and his 16 errors in only 364 innings marked him as one of the worst defenders in the league. He was strong-armed but wild, earning the nickname Buckshot Brown, because “you know how buckshot scatters.”73 Tommy started 1945 with the Dodgers’ top affiliate in St. Paul before finishing the season back in Brooklyn, where he became the only 17-year-old to date to homer in a big-league game. He found his niche as a backup shortstop with the Dodgers, Phillies, and Chicago Cubs through 1953, eventually settling into the high minors before retiring for good in 1959. As of this writing, Tommy Brown is alive and well and living in Brentwood, Tennessee.74

Tommy Brown holds two distinctions: he is the youngest 16-year-old player of the twentieth century, and he is the only starting position player on this list. He appeared in more games as a 16-year-old than any other player in major league history. The Dodgers did not bring Tommy to Ebbets Field as a novelty — they brought him there to play. Signed by the club after an open tryout, he was assigned to their Class B Newport News farm club and showed some serious skills there. Tommy was leading the Piedmont League in triples, as well as socking 21 doubles and even a towering home run over a right-center field fence, practically forcing the then last-place Brooklyns to purchase his contract on July 28.68, 69, 70 So popular was Tommy in Newport News that they held a “day” in his honor before he left, and the local paper continued to report on his performance while he was with the Dodgers.71 But Tommy wasn’t a big deal just in Virginia — New York papers wrote feature pieces heralding the arrival of the Dodgers’ new boy wonder.72 Unique among 16-year-olds, Tommy was immediately installed by his team as their starting shortstop. He had a promising start, clouting a double and scoring a run in his debut, and was batting .278 after his first six games. Alas, his youthful inexperience eventually caught up with him: his batting average plummeted below .200 for good by Labor Day, and his 16 errors in only 364 innings marked him as one of the worst defenders in the league. He was strong-armed but wild, earning the nickname Buckshot Brown, because “you know how buckshot scatters.”73 Tommy started 1945 with the Dodgers’ top affiliate in St. Paul before finishing the season back in Brooklyn, where he became the only 17-year-old to date to homer in a big-league game. He found his niche as a backup shortstop with the Dodgers, Phillies, and Chicago Cubs through 1953, eventually settling into the high minors before retiring for good in 1959. As of this writing, Tommy Brown is alive and well and living in Brentwood, Tennessee.74

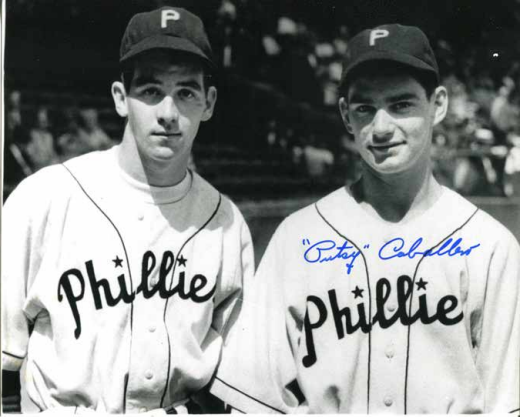

Position: Third Base

Born: November 5, 1927

Debut: September 14, 1944

Team: Philadelphia Phillies (National League)

Age: 16 years, 314 days

| G | PA | R | H | AVG | OBP | SLG | wRC+ | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | .000 | .000 | .000 | -100 | -0.2 |

Ralph “Putsy” Caballero was a two-sport star in his native New Orleans and was named to the all-American Legion team twice by the time he’d graduated high school in 1944 at age 16. But rather than taking a dual basketball/baseball scholarship to Louisiana State University, he decided to travel to Nashville to attend a tryout with the Cubs. His high school baseball coach was also a scout for the New York Giants; however, the Philadelphia Phillies, who had just undertaken efforts to sign high school-age talent, swooped in with an $8,000 bonus offer and stole Putsy out from under Giants manager (and fellow Louisiana native) Mel Ott.75 Although Ted McGraw, the Phillies scout who signed him, predicted Putsy would be a major leaguer in one year, he actually made his big-league debut just a week later in the eighth inning of an 11-1 blowout at the hands of the Giants.76 Putsy did mop-up duty at third base, where he handled one chance, a pop fly from (coincidentally) Mel Ott, and went 0-for-1 at the plate, a popout to short. He appeared in three more games as a 16-year-old: twice as pinch runner, and once as a pinch hitter-turned-third baseman in another blowout. Putsy spent parts of seven more seasons with the Phillies, finishing his career at age 27 in 1955 after three more seasons with their AAA teams in Baltimore and Syracuse. He went into his father-in-law’s extermination business and then ran his own business until his retirement in 1997. Putsy Caballero passed away in New Orleans in 2016 at the age of 89.77

Ralph “Putsy” Caballero was a two-sport star in his native New Orleans and was named to the all-American Legion team twice by the time he’d graduated high school in 1944 at age 16. But rather than taking a dual basketball/baseball scholarship to Louisiana State University, he decided to travel to Nashville to attend a tryout with the Cubs. His high school baseball coach was also a scout for the New York Giants; however, the Philadelphia Phillies, who had just undertaken efforts to sign high school-age talent, swooped in with an $8,000 bonus offer and stole Putsy out from under Giants manager (and fellow Louisiana native) Mel Ott.75 Although Ted McGraw, the Phillies scout who signed him, predicted Putsy would be a major leaguer in one year, he actually made his big-league debut just a week later in the eighth inning of an 11-1 blowout at the hands of the Giants.76 Putsy did mop-up duty at third base, where he handled one chance, a pop fly from (coincidentally) Mel Ott, and went 0-for-1 at the plate, a popout to short. He appeared in three more games as a 16-year-old: twice as pinch runner, and once as a pinch hitter-turned-third baseman in another blowout. Putsy spent parts of seven more seasons with the Phillies, finishing his career at age 27 in 1955 after three more seasons with their AAA teams in Baltimore and Syracuse. He went into his father-in-law’s extermination business and then ran his own business until his retirement in 1997. Putsy Caballero passed away in New Orleans in 2016 at the age of 89.77

Position: Shortstop

Born: September 27, 1938

Debut: September 16, 1955

Team: Kansas City Athletics (American League)

Age: 16 years, 354 days

| G | PA | R | H | AVG | OBP | SLG | wRC+ | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 11 | 0 | 1 | .100 | .182 | .100 | -23 | -0.3 |

The first of the two 16-year-old players of the 1950s was a locally famous four-sport superstar at Kansas City’s Parkhurst High School who graduated early and was all set to enroll and play basketball and baseball at the University of Kansas when the Athletics came calling. On September 15, they signed him to a contract with an $18,000 bonus, spread over two years, that mysteriously fell outside the Bonus Baby rules of the time, which stated if a first-time amateur received a bonus over $4,000, he had to be placed on the team’s big-league roster for two seasons.78 Even so, while the A’s could have — indeed, should have — sent Alex immediately to the minors for seasoning, they instead inserted him into the very next day’s game against the Chicago White Sox as a pinch hitter. Sherm Lollar, the catcher, told him every pitch that was coming, and Alex still struck out.79 It didn’t get any better for Alex from there: he appeared at the plate eleven times in five games, struck out in seven of those trips, took one walk and got one hit, a drag bunt single.80 The following season he was sent to Class D Fitzgerald in the Georgia-Florida League and rode buses for the next eight seasons, rising as high as AA, but never getting another crack at the majors. Alex quit baseball in 1963 at age 24, then went into ad sales for local radio and TV stations in Kansas City. As of this writing, Alex George still lives in Prairie Village, Kansas, a suburb of his hometown.81

The first of the two 16-year-old players of the 1950s was a locally famous four-sport superstar at Kansas City’s Parkhurst High School who graduated early and was all set to enroll and play basketball and baseball at the University of Kansas when the Athletics came calling. On September 15, they signed him to a contract with an $18,000 bonus, spread over two years, that mysteriously fell outside the Bonus Baby rules of the time, which stated if a first-time amateur received a bonus over $4,000, he had to be placed on the team’s big-league roster for two seasons.78 Even so, while the A’s could have — indeed, should have — sent Alex immediately to the minors for seasoning, they instead inserted him into the very next day’s game against the Chicago White Sox as a pinch hitter. Sherm Lollar, the catcher, told him every pitch that was coming, and Alex still struck out.79 It didn’t get any better for Alex from there: he appeared at the plate eleven times in five games, struck out in seven of those trips, took one walk and got one hit, a drag bunt single.80 The following season he was sent to Class D Fitzgerald in the Georgia-Florida League and rode buses for the next eight seasons, rising as high as AA, but never getting another crack at the majors. Alex quit baseball in 1963 at age 24, then went into ad sales for local radio and TV stations in Kansas City. As of this writing, Alex George still lives in Prairie Village, Kansas, a suburb of his hometown.81

Position: Pitcher

Born: November 29, 1939

Debut: September 30, 1956

Team: Chicago White Sox (American League)

Age: 16 years, 306 days

| G | GS | W | L | ERA | IP | WHIP | ERA- | fWAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7.50 | 6 | 2.50 | 182 | -0.2 |

Jim was a bona fide Bonus Baby, having signed for $78,000.82 The White Sox had high enough hopes for him that they signed the 16-year-old knowing that, by major league rules, they would have to carry him on their big-league roster for two seasons. They had good reason to be optimistic: Jim, ace pitcher-first baseman for South Gate High School, had been named Los Angeles All-City Player of the Year earlier that summer of 1956, during which he went 10–2, struck out 159 in 88 innings, had a 0.23 ERA, batted .452, and threw at least two no-hitters.83, 84, 85 Jim was given the start of the final game of the 1956 season in Kansas City against the Athletics and, for a still-growing boy, pitched a man-sized game: 31 batters faced, six innings, six runs (five earned) on nine hits (two homers) and six walks (five on 3–2 pitches), and three strikeouts. He took the 7–6 loss when the Chisox fell just short on their comeback bid. Jim came to bat twice, striking out his first time up but singling to right on his second trip, before he was lifted for pinch hitter Larry Doby in the seventh.86 Jim remains the youngest pitcher since 1876 to start a major league gam. Bonus Baby rules dictated his return to the big club in 1957, during which he appeared in 37 innings across 20 games, including five starts, and finished with a 4.86 ERA. After that, Jim suffered the same fate so many other 16-year-old major leaguers did: he kicked around the minors for a few years before retiring from the game after the 1961 season at the tender age of 21. After baseball, Jim Derrington worked at a variety of jobs and coaching gigs in the LA area, where he still lives as of this writing.87

Jim was a bona fide Bonus Baby, having signed for $78,000.82 The White Sox had high enough hopes for him that they signed the 16-year-old knowing that, by major league rules, they would have to carry him on their big-league roster for two seasons. They had good reason to be optimistic: Jim, ace pitcher-first baseman for South Gate High School, had been named Los Angeles All-City Player of the Year earlier that summer of 1956, during which he went 10–2, struck out 159 in 88 innings, had a 0.23 ERA, batted .452, and threw at least two no-hitters.83, 84, 85 Jim was given the start of the final game of the 1956 season in Kansas City against the Athletics and, for a still-growing boy, pitched a man-sized game: 31 batters faced, six innings, six runs (five earned) on nine hits (two homers) and six walks (five on 3–2 pitches), and three strikeouts. He took the 7–6 loss when the Chisox fell just short on their comeback bid. Jim came to bat twice, striking out his first time up but singling to right on his second trip, before he was lifted for pinch hitter Larry Doby in the seventh.86 Jim remains the youngest pitcher since 1876 to start a major league gam. Bonus Baby rules dictated his return to the big club in 1957, during which he appeared in 37 innings across 20 games, including five starts, and finished with a 4.86 ERA. After that, Jim suffered the same fate so many other 16-year-old major leaguers did: he kicked around the minors for a few years before retiring from the game after the 1961 season at the tender age of 21. After baseball, Jim Derrington worked at a variety of jobs and coaching gigs in the LA area, where he still lives as of this writing.87

Those are the fifteen 16-year-old major leaguers. In major–league terms, nearly all of them performed awfully, as would be expected. So the question now becomes:

2. Under what circumstances could a 16-year-old have been allowed to play major-league baseball in the first place?

It should barely rate mention that a 16-year-old boy would be a suboptimal choice for a spot on a major-league roster, not only because his physical strength is still more than a decade away from its peak, but also because his baseball skills are still in the early stages of development.88 After all, it’s a safe bet that most players on any given major league roster have already been playing the game for more than 16 years, let alone having been alive for that long. Experience matters.

Nevertheless, there are certain rare circumstances when it might actually make sense for a 16-year-old to be included on a major league roster. Three major circumstances are:

A. The game of baseball was so new, hardly anybody was an expert at playing it. This was obviously true in the very early days. The first clubs that played what most resembles today’s game of baseball were founded in New York between the late 1830s and mid-1840s. However, key rules — such as nine innings per game, nine men per side, and ninety feet between bases — were not officially codified until 1857 by the Convention of Base Ball Clubs, and the first professional league launched a mere 14 years later.89, 90 At that time, playing baseball for money was still considered by many to be a disreputable activity, the province of gamblers and corruptible players, casting a pall on its integrity.91 Even as the game began to “[gain] in popularity, never before equaled by anything of the sort invented,” many believed the game should remain an amateur affair, contested strictly for love of competition and not for the crass goal of making money and thus reducing the game ”to the level of horse racing and other gambling pursuits.”92, 93 This controversy may have had the effect of restricting the flow of some of the better ballplayers to professional leagues during its first few years.

In addition, the earliest baseball leagues for children did not form until the 1880s (and even those that were established did not flourish). Children could play sandlot ball, but with substandard equipment that was invariably adult sized.94 As such, it would have been exceedingly difficult for children to acquire advanced baseball expertise. Since organized baseball activity was essentially non-existent for children before 1871, a large age cohort of boys from this era could not have achieved enough proficiency to ensure a tightly-aged group of the highest-skilled professional players. Of the cohort we would consider to be of peak professional baseball age, only a small sliver — much smaller than today — would have been available to play, simply because so many had still not played the game to a serious enough degree to do so professionally.

In other words, just about anybody of this era with a rugged enough body who could learn to play the game as an adult with a passable level of skill would have been considered suitable to play professional “base ball.” As a result, the early and middle 1870s saw some of the highest compositions of both teenage players95 — and players96 over 35— in professional baseball history.

B. World War II. This particular war took a drastic toll on professional baseball’s player pool. Unlike the first World War, which for the United States spanned only the 1917 and 1918 seasons, the second great war lasted almost four complete seasons. In the immediate shock of Pearl Harbor and the declaration of a two-front war, the major leagues continued with business as usual, as affirmed by President Roosevelt’s famous “Green Light” letter.97, 98 Even so, more than 500 major-leaguers and over 4,000 minor-leaguers “swapped flannels for khakis” during this period.99

This obviously created a shortage of professional-quality ballplayers, so the pool of candidates had to be widened outside the boundaries of draft age, which in November 1942 Congress expanded to ages 18 to 37.100 As a result, 1944 saw ten 16- and 17-year-old players in the majors, by far the most of any season in history.101 (The 1944–45 seasons also saw the highest composition of players age 38 and older by a wide margin.102) Several ballclubs actively sought underage ballplayers — notably the Dodgers (six) and Phillies (five) — to “man” positions for their teams.103 The Dodgers conducted tryouts across the country, sending letters to 20,000 coaches and others “requesting recommendations of promising athletes.” One camp in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, drew 252 teenage hopefuls.104 Perhaps not surprisingly, these two clubs also occupied the bottom two slots of the 1944 National League standings. Other clubs such as the Giants — led by Mel Ott, a former 17-year-old major leaguer himself — recruited underage players to populate the rosters of their minor league affiliates. This allowed them to call up minor leaguers — themselves bereft of true major league skill, but at least possessing the quality of adulthood — to sip their own cups of coffee courtesy of the wartime talent shortage.105

C. The Bonus Baby Rule. Implemented by MLB in 1947, the Bonus Baby rule was intended to prevent the wealthiest clubs — e.g., Yankees, Boston Red Sox, Dodgers, Cardinals — from using their vast financial resources to sign all the best amateur talent and then stash them away in their farm systems.106 The original Bonus Baby rule was weak and eventually rescinded in 1950, but was reinstated in 1952 in stronger form: any “Baby” signed for more than a $4,000 bonus was required to be assigned to the major league roster for a full two years, or else be exposed to the waiver wire.107

This led to some teams deciding that signing incredibly young, barely proven talent would be worth the risk of major bonus money and potentially wasting a mandated roster spot on them — at least in principle. In practice, the rule was routinely circumvented by many teams, accompanied by rumors of secret under-the-table payments to signees to avoid the two-year-rostering part of the rule.108 This may have been true of Alex George in 1955, who relayed in an interview that his bonus was $18,000, paid to him across two years. It is likely that the Athletics found some loophole that allowed them to exceed the $4,000 Bonus Baby Rule limit while also allowing them to ship Alex out to Class D Fitzgerald for his second season.

The rule also led to the signing of Jim Derrington, the only acknowledged 16-year-old Bonus Baby, who remained with the White Sox for his age-17 season. Typical of how disrespected the rule was, even Jim’s bonus was misstated: widely reported as being $50,000, Derrington confirmed in an interview that the true amount was $78,000, simply because “that’s the way it was done.”109

The Bonus Baby rule led to an uptick in both 17- and 18-year-old big-league players as well. In the seven seasons between the war and the second Bonus Baby rule, only two 17-year-olds reached the majors; during the years 1953-1957, fifteen littered various big-league rosters.110 Also, in 1955 there were nine 18-year-old big leaguers, and in 1957 there were eight, the highest totals in a single season since 1912.111

The Bonus Baby rule was rescinded in December 1957 for multiple reasons — it penalized “honest” teams, young Babies suffered “arrested development” sitting unused on a big-league bench for two whole seasons, and the rule was so widely flouted anyway.112,113. Without it, the incentive to place a 16-year-old boy on a big-league roster disappeared for good.

There has not been a 16-year-old major league player in the six-plus decades since, which leads to the question:

3. Is it possible that a 16-year-old could ever play in the major leagues again?

Technically, yes. Practically, no.

Two sets of rules govern a team’s acquisition of first-time amateur talent, pertaining to either the First-Year Player Draft or signing of amateur free agents.

The draft is the only way for players in the United States and Canada to join a team in either Major League Baseball or their affiliated minor leagues — together: Organized Baseball.114 (The professional leagues independent of Organized Baseball, such as the Frontier League and Atlantic League, provide no direct path to the big leagues and explicitly stipulate a minimum age of 18 years.115, 116) As of 2019, to be draft-eligible a player must have completed four years of high school or at least one year of junior college. There is no explicit age requirement, which leaves open the possibility that a player could be eligible for the draft as a four-year high school graduate at age 16. A player is also eligible if he graduates from high school in three years (i.e., received a diploma after 11th grade) and he will be 17 years old within 45 days after the draft, again leaving open the possibility of being drafted at age 16.117

So, technically, a drafted player could enter Organized Baseball at the age of 16 and go directly to the major leagues to play. In real terms, however, draft rules are designed to make this a practical impossibility. During the first 54 years of the amateur draft, the youngest player ever selected was Alfredo Escalera, age 17 years and 114 days, in 2012.118 Beyond this, only four drafted high schoolers have gone directly to the majors once they were selected: David Clyde in 1973, and Tim Conroy, Brian Milner, and Mike Morgan, all in 1978, and all having already turned 18.119

A player living outside the US and Canada (i.e., a foreign player) has a marginally better chance of making the major leagues at age 16, although it is still practically as unlikely. A foreign player may enter Organized Baseball under contract as an amateur free agent if he is age 16 at the time of the signing, but only if he turns 17 prior to September 1 of the first season covered by the contract.120 Therefore, it is technically possible for a 16-year-old whose birthday is in late August to be signed during the winter and then play almost an entire season in professional ball as a 16-year-old. Jefferson Encarnacion (born August 28, 2001) did this in 2018. However, he, along with the vast majority of 16-year-old professional ballplayers, played in the Dominican Summer League (DSL), a short-season rookie league designed specifically to launch the careers of still-underage foreign-born talent signed as amateur free agents.

As such, very few foreign players make it onto an American diamond as 16-year-old professionals. According to Baseball-Reference, from 2009 through 2018, there were 355 sixteen-year-old professional baseball players. Ninety-three percent of them played exclusively in either the DSL or the Venezuelan Summer League (suspended in 2015). Of those 16-year-olds that did play pro ball in America, fifteen played in the Gulf Coast League, eight in the Arizona League, two in the Pioneer League and one in the Appalachian League — all rookie leagues. Not a single player during this period made it even as high as short-season A at age 16.

Adding all this up, it is clear the system is simply not designed to shortcut 16-year-old players directly onto major league rosters. Indeed, since the founding of the DSL in 1985, the youngest Dominican player to reach the majors has been Adrian Beltre, who debuted at 19 years and 78 days, and only after he had apprenticed in the minor leagues for 318 games.

To illustrate once more the extreme unlikelihood of a 16-year-old player ever again making a big-league roster, briefly consider the case of one of the best and most-hyped high school players of our time: Bryce Harper, who first broke through America’s consciousness on the cover of Sports Illustrated in June 2009. That October, he earned his GED after his sophomore year specifically to accelerate his eligibility for the draft by one year. To satisfy draft eligibility requirements, he enrolled in a Nevada junior college for the 2010 season, where he put up astounding numbers (.443/.526/.987 in 272 plate appearances).121 The Washington Nationals selected Bryce Harper number one overall in the 2010 draft. He was already age 17 years, 224 days. And instead of putting the greatest underage hitter in recent memory directly onto their major-league roster, the Nationals sent him to the minors for 164 games of seasoning. This is consistent with contemporary baseball practice. Since 1996, only two drafted players have gone directly to the majors without minor-league experience, both college graduates past their 21st birthdays.122

The inescapable conclusion is that — given the vast physical and developmental differences between high school age boys and grown men, combined with the stringent way in which the acquisition of amateur talent is regulated, and the process by which major league organizations develop that talent — we will not see another 16-year-old play major league baseball again.

CHUCK HILDEBRANDT has served as chair of the Baseball and the Media Committee since its inception in 2013. Chuck is a two-time Doug Pappas Award winner for his oral presentations “‘Little League Home Runs’ in MLB History” (2015) and “Does Changing Leagues Affect Player Performance, and How?” (2017), and authored the cover story for the Spring 2015 Baseball Research Journal, “The Retroactive All-Star Game Project.” Chuck lives with his lovely wife Terrie in Chicago, where he also plays in an adult hardball league. Chuck has also been a Chicago Cubs season ticket holder since 1999, although he is a proud native of Detroit. So, while Chuck’s checkbook may belong to the Cubs, his heart still belongs to the Tigers.

Table 1: Season and Career Records for All 16-Year-Old Major Leaguers

(Click image to enlarge.)

Notes

1 “Lad of Fifteen Picked by Reds To Do Hurling,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 19, 1944.

2 “Maybe You Need Different Glasses, Deacon! Things First Look Rosy, Then Gloomy,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 5, 1944.

3 Davis J. Walsh, ”Reds to Expect Great Things From Hamilton Rookie, Joe Nuxhall,” The Daily Herald (Circleville (O.)), March 29, 1944.

4 Si Burick, “15-Year-Old Joe Nuxhall Tagged A Typical Southpaw; “Plays Hooky” To Sit With Reds On Opening Day,” Dayton (O.) Daily News, April 19, 1944.

5 Oscar Fraley, “Two Items: Definite With Deacon; Baseball To Keep Rolling, View Of McKechnie, Who Also Opines That Redlegs Cannot Be Counted Out — Nuxhall Is Lauded.” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 26, 1944.

6 Paul B. Mason, “Kid Pitcher Thrilled By Big League Chance,” The Times Recorder (Zanesville, O.), June 13, 1944.

7 Al Cartwright, “School’s Out, Nuxhall Joins Reds,” The Dayton (O.) Herald, June 8, 1944.

8 Except where noted, all career and game statistics are sourced from either Baseball-Reference.com or Retrosheet.org.

9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “2 to 20 years: Boys Stature-for-age and Weight-for-age percentiles,” published May 30, 2000 (modified November 21, 2000).

10 Baseball-Reference.com Play Index, “For Single Seasons, From 1871 to 2018, For age 16, sorted by earliest date,” accessed February 15, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/tiny/C9qSv (case-sensitive).

11 “Weighted Runs Created Plus (wRC+) is a rate statistic which attempts to credit a hitter for the value of each outcome (single, double, etc) rather than treating all hits or times on base equally, while also controlling for park effects and current run environment,” Steve Slowinski, “wRC and wRC+,” February 16, 2010, accessed February 15, 2019, https://library.fangraphs.com/offense/wrc/. Note: 100 represents average.

12 “Wins Above Replacement (WAR) is an attempt by the sabermetric baseball community to summarize a player’s total contributions to their team in one statistic,” Steve Slowinski, “What is WAR?,” February 15, 2010, accessed February 15, 2019, https://library.fangraphs.com/misc/war/. Note: fWAR represents Fangraphs’s calculation of the statistic, as distinct from bWAR, which is Baseball-Reference’s calculation.

13 Although in 1968 the Special Baseball Records Committee ruled that the National Association, which was active from 1871 to 1875, was not to be considered a major league, consistent with the National Association’s appearance in major league research sources such as Retrosheet, it is included here.

14 John Thorn, “Why Is the National Association Not a Major League … and Other Records Issues, May 4, 2015, accessed February 19. 2019, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/why-is-the-national-association-not-a-major-league-and-other-records-issues-7507e1683b66.

15 “ERA- … [is a] park and league adjusted [version] of ERA … These ‘minus’ stats make it easier to compare pitchers regardless of the underlying run environment, as different parks, leagues and seasons can influence a pitcher’s raw numbers. League average is set to 100 for each season and each point below or above 100 is one percentage point better or worse than league average,” Steve Slowinski, “ERA- / FIP- / xFIP-“, April 8, 2011, accessed February 15, 2019, https://library.fangraphs.com/pitching/era-fip-xfip/.

16 Fangraphs’s reported WAR for Jim Britt, of 5.3 for a pitcher who is 9-28 with a 120 ERA-, does not “pass the smell test,” so Baseball-Reference’s version of WAR is reported here.

17 “Sports and Pastimes. Base Ball,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, May 21, 1872.

18 “Sports and Pastimes. Base Ball,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, April 8, 1872.

19 “Sports and Pastimes. Base Ball,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, May 4, 1872.

20 “Sports and Pastimes. Base Ball,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, April 20, 1872.

21 “Sports and Pastimes. Base Ball,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, April 27, 1872.

22 “Sports and Pastimes. Base Ball,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, May 1, 1872.

23 “Sports and Pastimes. Base Ball,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, May 21, 1872.

24 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books), 21

25 “Base-Ball. Louisvilles vs. Hartfords,” The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Ky.), October 5, 1876.

26 Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game, 67.

27 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 2: The Hall of Famers and Memorable Personalities Who Shaped the Game (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books), 321

28 “The Colleges. A Rainy Class Day at Princeton. The Festivities Marred by the Disagreeable Weather. A List of the Graduates — A Description of he New Library at Lehigh University to be Dedicated This Week,” The Times (Philadelphia), June 19, 1878.

29 “The Jumbos Floored. Another Expedition of Muscular Giants Bagged Between Bases., The Stannards of St. Louis Follow the Footprints of the “Reds,” And Retire from the Field Minus Their Scalps,” Omaha (Neb.) Daily Bee, August 28, 1882.

30 “Well Whitewashed. The Union Pacifics Receive Nothing But Goose Eggs, While the Council Bluffs Get One Tally,” Omaha (Neb.) Daily Bee, September 25, 1882.

31 “Again Downed. The Union Pacifics Suffer Another Defeat at the Hands of the Council Bluffs Nine,” Omaha (Neb.) Daily Bee, October 23, 1882.

32 “Leonidas P. Funkhouser,” The Courier (Lincoln, Neb.), March 15, 1902.

33 [News item without title], The Haddam (Kan.) Clipper-Leader, June 21, 1912, 2.

34 “A Great Battle of Bats. Victory Won After Twelve Innings. A Remarkable Game of Base Ball at Recreation Park — The Philadelphia Club Defeats the Cleveland by a Score of 4 to 3 — The Athletics Win,” The Times (Philadelphia), June 13, 1883.

35 “Piggy Ward Dead, Once Played Here,” Hartford (Conn.) Courant, October 26, 1912.

36 Society for American Baseball Research, Baseball’s First Stars (Phoenix: SABR), 105.

37 “Haddock Hammered. Cleveland Paying Buffalo Back With Interest. The Internationals Also Beaten — League and Association Scores — Sports of All Sorts,” The Buffalo (N.Y.) Express, May 9, 1890.

38 Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game, 127.

39 Society for American Baseball Research, Baseball’s First Stars, 105.

40 Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game, 127.

41 “William (Wee Willie) McGill, Major League Pitcher in 1890s, Dies Here,” The Indianapolis Star, August 31, 1944.

42 Tom Hess player card, accessed February 15, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=hess–001tho,

43 “Pity Poor Anson. His Colts Scamper in Confusion Before the Orioles. Overwhelmed by a Score of 23 to 1. Great Batting and Fine Fielding and Base-Running Against Chicago — President Harrison Sees the Washington Game — Other Contests,” The Sun (Baltimore), June 7, 1892.

44 David Nemec, The Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball: Biographies of 1,084 Players, Owners, Managers and Umpires (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland), 107

45 “Slugging Won the First Game. The Reds at Last Find Their Batting Eyes And Pound McJames To Their Hearts Content. ‘Twas Different in the Second Game at Washington — Baseball News,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, September 12, 1897.

46 Cincinnati Enquirer, September 12, 1897.

47 Joe Stanley player card, accessed February 15, 2019, https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/S/Pstanj103.htm.

48 Nemec, The Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball: Biographies of 1,084 Players, Owners, Managers and Umpires, 77

49 “Bonehead-Bonehead-Bonehead-Bonehead. Bartlesville Takes Three Straight From Midgets — Worst Game of the Season,” The Springfield (Mo.) Republican, July 6, 1909.

50 “Monett Beats Sarcoxie. Only Four Local Men Play In Cassville Game,” The Springfield (Mo.) Republican, August 7, 1909.

51 “Baseball,” The Springfield (Mo.) Republican, April 4, 1909.

52 “Baseball,” The Springfield (Mo.) Republican, April 6, 1909.

53 “Baseball,” The Springfield (Mo.) Republican, April 15, 1909.

54 “Railroaders Walloped Senators. Foot Racing Qualities of Visitors Declared Good,” The Guthrie (Okla.) Daily Leader, May 14, 1909.

55 “Line Drives,” The Muskogee (Okla.) Times-Democrat, May 26, 1909.

56 “Bonehead-Bonehead-Bonehead-Bonehead. Bartlesville Takes Three Straight From Midgets — Worst Game of the Season,” The Springfield (Mo.) Republican, July 6, 1909.

57 “Even Break at St. Louis Ends Superbas’ Western Trip. Swamp the Cardinals in the First Game and Lose the Second When Scanlon Blew Up — Record, Five Game Won; Ten Lose and Two Tied — Play at Boston To-Morrow,” The Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, August 16, 1909.

58 McKee’s record reflects only the two games (out of a season total of four) that he pitched while still age 16.

59 “‘Mail-Order’ Rajah Signed by Phillies,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Eagle, August 13, 1943.

60 “Baseball Break,” Des Moines (Ia.) Tribune, August 12, 1943.

61 “Pitcher McKee Enters Navy,” Mount Carmel (Pa.) Item, January 3, 1945.

62 Alan Ford, “Local baseball legend McKee passes away,” September 4, 2014, accessed February 15, 2019, https://www.shelbystar.com/20140904/local-baseball-legend-mckee-passes-away/309049793.

63 “Sport Shots,” Mount Carmel (Pa.) Item, September 1, 1942.

64 Jim Sargent, “Carl Scheib,” accessed February 15, 2019, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/93562fe6.

65 “Gratz Hurler Bought by Phila. Athletics,” The Elizabethville (Pa.) Echo, September 9, 1943.

66 “Sport Shots,” Mount Carmel (Pa.) Item, September 10, 1943.

67 “Sport Shots,” Mount Carmel (Pa.) Item, September 9, 1943.

68 C. Paul Rogers III, “Tommy Brown,” SABR BioProject, accessed February 15, 2019, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/7913ae6c.

69 Vann Dunford, “Codde Right, Dodgers Trim Cards By 9 To 3. Blast Couple of Hurlers for Eleven Bingles,” Daily Press (Newport News, Va.), June 18, 1944.

70 “Brooklyn Dodgers Purchase Tom Brown,” Daily Press (Newport News, Va.), July 29, 1944.

71 Vann Dunford, “Dodgers Lose ‘Pitler Day’ Tilt To Tars, 16-2. Norfolk Homers Spell Locals’ Doom As Visitors Thump Out 17 Safe Hits,” Daily Press (Newport News, Va.), July 31, 1944.

72 “Newcomers,” Daily News (New York), August 4, 1944.

73 “Schultz Ignores Low, Outside One — Poles 15 Hits,” Brooklyn (N.Y.) Eagle, September 5, 1944.

74 Rogers, “Tommy Brown,” https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/7913ae6c.

75 Jim Sweetman, “Putsy Caballero,” The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant — The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies (Phoenix: SABR), 45.

76 Stan Baumgartner, “Caballero, 16, Signed by Phils,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 10, 1944.

77 Sweetman, “Putsy Caballero,” 45.

78 Dan Blom, “Prairie Village’s Alex George played major league baseball with the Kansas City Athletics as a 16-year-old,” October 30, 2014, accessed February 16, 2019, https://shawneemissionpost.com/2014/10/30/prairie-villages-alex-george-played-major-league-ball-kansas-city-athletics-16-year-old-33366.

79 “Lollar Called Pitches, But A’s Rookie Whiffed Anyhow,” Sporting News, September 26, 1955.

80 Blair Kerkhoff, “Can you imagine a 16-year-old playing in the majors? This Rockhurst grad did, for the KC Athletics”, The Kansas City Star, June 8, 2018.

81 Blom, “Prairie Village’s Alex George.’

82 Brent P. Kelley, Baseball’s Bonus Babies: Conversations With 24 High-priced Ballplayers Signed from 1953 to 1957 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland), 84.

83 “Four Valley League Players on All-City,” The Valley News (Van Nuys, Calif.), June 10, 1956.

84 “South Gate’s Derrington Signs Chisox Bonus Pact,” Los Angeles Times, September 11, 1956.

85 “Derrington Registers His Second No-Hitter,” Los Angeles Times, May 30, 1956.

86 Robert Cromie, “Bonus Hurler and Sox Lose to A’s, 7 to 6,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 1, 1956.

87 Tom Birschbach, “He Started for the White Sox at 16, but Was Through at 22,” Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1991.

88 Samantha Olson, “How Old Is Usain Bolt? Fastest Man In The World Tests His Age In 100-Meter Sprint,” August 14, 2016, accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.medicaldaily.com/usain-bolt-fastest-man-world-394814.

89 John Thorn, “Origins of the New York Game: How did a regional game become the national pastime?,” accessed March 4, 2019, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/origins-of-the-new-york-game-bf9b330042d6.

90 John Thorn, “Nine Innings, Nine Players, Ninety Feet, and Other Changes: The Recodification of Base Ball Rules in 1857,” August 22, 2012, accessed March 4, 2019, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/nine-innings-nine-players-ninety-feet-and-other-changes-the-recodification-of-base-ball-rules-in-39684873f818.

91 Aaron Feldman, “Baseball’s Transition to Professionalism,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://sabr.org/sites/default/files/feldman_2002.pdf.

92 “Base-Ball,” Louisville (Ky.) Journal, May 1, 1868.

93 “Base Ball Gambling,” The Brooklyn (N.Y.) Daily Eagle, April 10, 1868.

94 “History of Little League,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.littleleague.org/who-we-are/history/.

95 “For Single Seasons, From 1871 to 2018, From Age 16 to 19, sorted by greatest number of players matching criteria in a single season,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/tiny/oNjtV (case-sensitive).

96 “For Single Seasons, From 1871 to 2018, From Age 35 to 99, sorted by greatest number of players matching criteria in a single season,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/tiny/BqfEi (case-sensitive).

97 “Major Leagues Plan ‘Business as Usual,” The State Journal (Lansing, Mich.), January 14, 1942.

98 Shirley Povich, “’Green Light’ from No. 1 Umpire Rallies Game Through Nation,” Sporting News, January 22, 1942, 1.h

99 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball in World War II“, accessed February 16, 2019, http://www.baseballinwartime.com/baseball_in_wwii/baseball_in_wwii.htm

100 “Draft age is lowered to 18,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/draft-age-is-lowered-to-18

101 “For Single Seasons, From 1871 to 2018, From Age 16 to 17, sorted by greatest number of players matching criteria in a single season,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/tiny/2pwJ9 (case-sensitive).

102 “For Single Seasons, From 1871 to 2018, From Age 38 to 98, sorted by greatest number of players matching criteria in a single season,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/tiny/xwihn (case-sensitive).

103 “For Single Seasons, From 1942 to 1946, From Age 16 to 17, sorted by most recent date,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/tiny/7R65w (case-sensitive).

104 Don Basenfelder, “Rickey Scouts Scour U.S. for Teen-Age Prospects,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1943, 7.

105 Ken Smith, “Mel Ott to Test 20 Youngsters,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1944, 12.

106 Steve Treder, “Cash in the Cradle: The Bonus Babies,” November 1, 2004, accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/cash-in-the-cradle-the-bonus-babies/.

107 Robert F. Burk, Much More Than a Game: Players, Owners, and American Baseball since 1921 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press), 127.

108 Treder, “Cash in the Cradle: The Bonus Babies,” https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/cash-in-the-cradle-the-bonus-babies/.

109 Kelley, Baseball’s Bonus Babies: Conversations With 24 High-priced Ballplayers Signed from 1953 to 1957, 84.

110 “For Single Seasons, From 1871 to 2018, For age 17, sorted by greatest number of players matching criteria in a single season,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/tiny/5y1s8 (case-sensitive).

111 “For Single Seasons, From 1871 to 2018, For age 18, sorted by greatest number of players matching criteria in a single season,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.baseball-reference.com/tiny/GMFGZ (case-sensitive).

112 Edgar Munzel, “Bankrolls Now Only Limit on Bonus Bids,” Sporting News, December 18, 1957, 11.

113 Ray Gillespie, “Busch to Lead Fight to Put End to Bonus Rule,” Sporting News, October 9, 1957, 1.

114 For the purposes of the draft, The United States also includes its territories, e.g., Puerto Rico.

115 “Player Eligibility,” accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.frontierleague.com/league/player-eligibility/

116 “Open Tryouts For Many Atlantic League Teams,” accessed February 16, 2019, http://atlanticleague.com/about/newswire/index.html?article_id=411

117 “MLR 3(a)” The Official Professional Baseball Rules Book (New York: Office of the Commissioner of Baseball, 2018), 32.

118 Globalize LLC, “Royals Draft The Youngest Player In Baseball History,” June 7, 2012, accessed February 16, 2019, http://www.i70baseball.com/2012/06/07/royals-draft-the-youngest-player-in-baseball-history/

119 “Straight to the Major Leagues”, accessed February 16, 2019, http://www.baseball-almanac.com/feats/feats9.shtml. (NOTE: Although Brian Milner is listed at this source as having gone directly to the majors in 1978 from Texas Christian University, contemporaneous reports of the time confirm that he was indeed drafted out of Southwest High School in Fort Worth Texas. Example: “Pro Draft,” The Tampa Times, June 8, 1978, page 10.)

120 “MLR 3(a)”, The Official Professional Baseball Rules Book, 32.

121 Bryce Harper player card, accessed February 16, 2019, http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=156293 (case-sensitive).

122 “Straight to the Major Leagues,” http://www.baseball-almanac.com/feats/feats9.shtml.