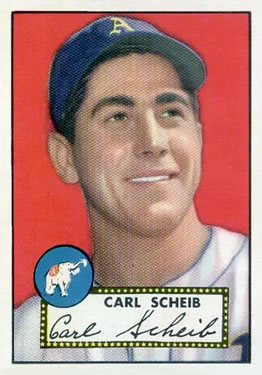

Carl Scheib

By the time Carl Scheib pitched his final major-league game in 1954, the big righthander from Gratz, Pennsylvania, had risen from the youngest player in American League history in 1943 to a solid performer who won 45 times and fashioned a lifetime 4.88 ERA. During his 11 major league seasons, he played all but two of his 267 games for the Philadelphia Athletics, a club that finished no higher than fourth place (1948 and 1952) during those years.

By the time Carl Scheib pitched his final major-league game in 1954, the big righthander from Gratz, Pennsylvania, had risen from the youngest player in American League history in 1943 to a solid performer who won 45 times and fashioned a lifetime 4.88 ERA. During his 11 major league seasons, he played all but two of his 267 games for the Philadelphia Athletics, a club that finished no higher than fourth place (1948 and 1952) during those years.

Scheib, modest, down-to-earth, and friendly, lived a remarkable baseball dream. He literally came off the farm, received a chance to pitch for the Athletics, worked in mop-up situations in late 1943 and during the 1944 season, served in the Army during much of 1945 and 1946, returned to the club for spring training and the 1947 season, and developed into a very good pitcher by the end of 1948. He pitched well until 1953, when he injured his shoulder. After a short stint with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1954, Carl pitched four years in the high minors before leaving the game for good.

Born on January 1, 1927, the youngest son of Oliver and Pauline Scheib, a Pennsylvania Dutch couple, Carl grew up on his family’s 10-acre farm near the small town of Gratz, located 50 miles north of Harrisburg in the middle of the state’s farming and coal mining region. Oliver liked baseball but never played the game. Instead, he would watch the Gratz town team play, often on Sundays. The Scheibs had three older children: Edna, the oldest, Alfreda, and Paul, who later caught during for two minor league ball clubs during the 1947 season. As boys growing up, Carl and Paul helped farm their father’s land and hired out to earn money working on bigger farms.

Gratz had a population of about 800. The town’s high school, which had less than three dozen pupils, fielded only a baseball team. In fact, during Carl’s time the school only had nine players on the team. Lloyd Bellis, the principal, served as coach. He began working with Carl when he was an eighth grader. A good all-around player who could hit well, the strong, hard-throwing youth pitched as well as played other positions–a typical circumstance for baseball players who came from small towns. In 1942, the first full year of World War II for the United States, the quiet fifteen-year-old, who stood over six feet tall and weighed 190 pounds, played for an American Legion team in nearby Lykens. Due to his impressive pitching and hitting, Scheib attracted the interest of area fans. One of those was a hometown grocery clerk.

Hannah Clark, who operated Smeltz’ Grocery in Gratz, had never seen a major league game–a fact probably true of the majority of Americans in the 1940s. But she knew enough about the national pastime to tell a curve ball from a fastball. Often Carl would stop by the store and buy a few items. Occasionally Hannah would speak to him about baseball. As a sophomore, Carl had won nine ball games. He was too shy to say much, so Hannah watched the high school team play in order to learn about him.

During the 1940s Connie Mack‘s Philadelphia Athletics didn’t operate an expensive farm system as did the St. Louis Cardinals, Brooklyn Dodgers, or Detroit Tigers. Instead, Mack and his associates relied largely on an informal network of old ballplayers, high school and college coaches, and other friendly sources. Hannah Clark had no connection with the Macks; figuring she would be ignored as a female fan, she spoke with Al Grossman, a traveling salesman who came through Gratz. Grossman, who had friends in the Athletics organization, liked what he heard. He wrote a letter to Connie Mack in mid-1942. Mack read the letter and–remembering how a liquor salesman (or so the story goes) once told Washington’s Clark Griffith about young Walter Johnson–replied, inviting the teenager to come to Philadelphia for a tryout.

On a rainy day in September 1942, Oliver Scheib drove his youngest boy to Philadelphia. The father and son found venerable Shibe Park. The A’s afternoon game had been called off due to the rain, but they walked into the ballpark. A coach summoned the elder Mack from his upstairs office. Carl remembered the scene well: “Mister Mack” asked him to throw in the bullpen. After a few minutes, Mack, then nearly eighty and a legend in baseball, told the young man he liked what he saw. But it was late in the season, and the A’s owner and manager advised Scheib to go back to school but to return as soon as he could the following spring.

In 1943, when Philadelphia was preparing for the regular season home opener at Shibe Park on April 23, Carl talked with his father, who encouraged him. Carl quit school and reported to the A’s. Connie Mack placed him on salary as a batting practice pitcher. Surprising his teammates, Scheib displayed good control, a hard fastball, and a sharp curve. That summer he began making road trips with the team. In late August he pitched in the second game of an exhibition double-header against the League Island Marines. The righthander was impressive, working four innings, allowing no hits, and striking out seven.

After the game, Connie Mack said, “Don’t you think it’s about time?” “I’m ready!” Carl replied.

The manpower drain of World War II meant that good players were at a premium. Mack, looking to the future, signed Scheib (his father co-signed with him) to a regular contract on Monday, September 6, 1943. Carl, nervous and tense, made his major league debut the same day. Playing at home, the A’s took on the New York Yankees in a twin bill. Scheib watched as the Mackmen won the opener, 11-2, behind the pitching of righthander Roger Wolff, a 33-year old knuckleballer who went 10-15 in 1943.

In the second game, Mack started rookie Don Black, a righthander with a good fastball. Black, who was 6-16 in 1943, worked eight innings, allowing seven hits and five runs. In the top of the ninth, Mack called Orie Arntzen, a 34-year-old righthander, from the bullpen. Arntzen retired one Yankee, but he walked two and gave up three hits. Scheib came out of the pen to finish the contest, allowing two hits and the final tally in a six-run inning.

For the remainder of 1943, Scheib saw occasional relief duty. The teenager appeared in 18.2 innings in six games, losing once but posting a respectable 4.34 ERA. Facing the Cleveland Indians at Shibe in the season finale on October 4, the A’s maintained a 4-4 tie into the eleventh inning. Scheib took the mound in the eighth and yielded five hits. But he gave up four of the hits and four runs in the top of the eleventh. The Tribe won, 8-4, clinching third place in the American League. Scheib took the loss, and the A’s finished in the cellar with a 49-105 ledger.

World War II affected major league baseball for four seasons. About three hundred big leaguers were serving in the military by 1944. Also, materials for making baseball equipment and balls were in short supply, spring training sites were moved north to reduce travel and ease the burden of moving troops by train, and games were often moved to twilight or at night, partly to accommodate fans who worked in factories. According to David M. Jordan in his excellent book The Philadelphia Athletics: Connie Mack’s White Elephants, 1901-1954 (1999), the National League’s Phillies and AL’s Athletics were hit harder than most teams. Both the A’s and the Phillies had trouble finding new, young talent, and neither club had much success with using untested minor leaguers or returning veteran players.

In 1944 Connie Mack, entering his forty-fourth season at the helm of the A’s, watched his club train in the chilly climate of Frederick, Maryland. Scheib’s first win came when he hurled an exhibition against the local Curtis Bay Coast Guard team on March 25. But Mack, figuring his teenager would be a good hurler in the future, didn’t allow Carl to make a single start in 1944. Appearing in 15 games, the righthander posted a 4.10 ERA but picked up no decisions.

Scheib gradually improved. On August 13 in Philadelphia, while the A’s lost to the Tigers, 6-0, he pitched a hitless and scoreless ninth. Two weeks later, at home in an 8-5 loss to the Red Sox, he gave up one hit but no runs in four innings. In his final appearance of 1944, against the Tigers at Briggs Stadium on September 26, Carl allowed two hits and no runs in the final four innings. But after piling up an early lead, Detroit won, 6-0.

Reflecting on his early years with the A’s, Scheib recalled, “When I first went to Philadelphia, I was a shy, bashful kid. I had never been away from home. I had never eaten in a restaurant. My parents drove me down and dropped me off the big city of Philadelphia, and, hey, it was rough! Most of the players had rooms in Philadelphia, and I had one by myself, too. I missed a lot of meals, living by myself. I had to find a restaurant to eat. I didn’t even know how to read a menu. I had never been 50 miles from home when I left. The Great Depression was just getting over, and our family never had the money to go anywhere or do anything.

“I was so innocent in those years before the war. I had never followed big league baseball, and now I was playing for the Athletics. I went down there for the tryout in 1942, and they told me to go get dressed, I didn’t have spikes. I didn’t have a glove. I didn’t have a uniform. I didn’t bring any equipment with me. They went from locker to locker to outfit me.

“I had a glove and my brother had a catcher’s mitt that our parents got us for Christmas presents. The gloves and a baseball were all my father could afford. When the chores were done, my brother and I would get out in our big front yard, and we’d throw and throw and throw. I would pitch and Paul would catch.”

In 1945 the A’s again trained at Frederick, Maryland, and Russ Christopher, the tall righthander who was the club’s top pitcher in 1944 with a 14-14 mark, became the team’s biggest holdout. But all the Mackmen were in the fold when April arrived, and Scheib hurled four scoreless innings in a 2-1 win over Toronto of the International League at nearby Hagerstown. Three days later in a 12-4 loss to the Curtis Bay Coast Guard, he gave up one safety in the final two frames.

Scheib had turned eighteen on January 1, 1945. After he had made only four appearances for the A’s, the Army drafted him. On May 5 at Griffith Stadium in Washington, the Nationals pounded Philadelphia’s Buck Newsom for 11 hits in four and a third innings. Scheib, in what turned out to be his final major league appearance for two years, blanked the Nats, allowing three hits the rest of the way. Six days later the 18-year-old was inducted into the Army.

The Army sent Scheib to Camp Wheeler in Georgia. Later, thanks to having major league experience, he pitched for the base team. By the end of the service season, Carl had won ten games, one of which was a no-hitter. He also helped the Seventh Battalion team win the camp’s championship. Then he was sent to two other bases to prepare for embarkation. On January 1, 1946, Scheib accompanied his unit to Germany. He began in the Railroad Transportation Division, but was transferred to the 60th Infantry of the Ninth Division.

In the summer of 1946 Scheib helped the 60th Regiment compile a 30-5 record and win the championship of the “American League” of service teams. Matched against the 508th Regiment, winners of the “National League” with a 38-4 mark, Scheib’s pitching and hitting played a big part in his team winning the “G.I. World Series” of occupied Germany. He won two games in the playoffs, and Dan Horn, from Pinconning, Michigan, won the title game. The good-hitting Gratz athlete played outfield when he didn’t pitch, and his bat contributed to the team’s victories.

Mustered out of the Army in late 1946, Scheib returned to the Athletics for spring training in 1947. He recalled working hard to get back into major league condition for the regular season. But he got off to a slow start, working mainly in long relief situations. The A’s also started slowly, occupying last place in the American League until May. The club posted a winning record for May and June, and rose as high as third place in late June. Philadelphia held onto fourth place until September, and slipped into fifth where the club finished the 1947 season.

The A’s had good personnel. Veteran righthander Phil Marchildon enjoyed his best year, going 19-9, while tall righthander Dick Fowler was 12-11. Recruit righthander Bill McCahan, in his first full season, and Russ Christopher, now a reliever, both won 10 games. Future batting champion and rookie first baseman Ferris Fain hit .291 with 71 RBI. Shortstop Eddie Joost, a longtime National Leaguer who was purchased from the St. Louis Cardinals in early 1946, hit 13 home runs, contributed 64 RBI, and fielded well. The outfield was solid. Sam Sam Chapman covered ground well in center field and led the team with 14 homers. Elmer Valo, the right fielder, hit .300 with 36 RBI, and Barney McCosky, in left, batted .328 with 52 RBI. Catcher Buddy Rosar had a fine season, hitting .259 and calling most of the games.

After several good relief outings in late May and early June, Scheib started at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium on June 11. He whitewashed the Tigers, 4-0, in the nightcap of a twin bill. The 20-year-old’s control wasn’t always sharp, as he walked seven and fanned only one batter. But he spaced seven hits and stranded 12 Tigers. At the plate Carl went 0-for-3, but his teammates exploded against Hal White in the sixth inning, scoring all four runs. Scheib, relying on his good fastball and sharp curve mixed with an occasional changeup, turned the 4-0 lead into the final score.

Six days later at Shibe Park, Carl stopped the Tigers again, 5-2. Detroit took a 2-1 lead in the top of the seventh on a walk, two singles, and Rosar’s first passed ball of the season. Detroit starter Al Benton walked Hank Majeski and Scheib to start the bottom of the inning. Joost sacrificed the runners along, and Benton gave an intentional pass to McCosky, loading the bases. Valo doubled home two runs, and Chapman doubled to score two more. Working before a crowd of 24,261, Scheib again made the lead stand up, scattering five Tiger hits.

On June 22, also at home, Scheib pitched the second game of a double-header against the Chicago White Sox and won, 3-0. The A’s grabbed a 1-0 lead when Chapman tripled and scored on a fly ball in the fourth inning. In the seventh the Mackmen strung together a walk, an error, a fly out, and Majeski’s double for the final two tallies. Backed by two double plays, Carl walked one batter, fanned two, and gave up just four hits. The 20-year-old, hyped by Philadelphia sportswriters as the “boy wonder,” recorded his third straight win and his second shutout.

Commented Scheib in 2006: “I guess the A’s decided I’d better start, or go to the minors. I started my first game against Detroit, and I beat ’em, 4-0. And I pitched another game, started it, and won that one, and I started another one, and won that one. Then I pitched at home, and the Yankees came in and beat me. I was getting lots of publicity at that time. We hardly ever drew big crowds, but the night I pitched against the Yankees we filled the stadium.”

Life in the majors can feel like a roller coaster ride for rookies, and Scheib was no exception. In a night game at home on June 27, the powerful Yankees bombed him and Bill McCahan for 12 hits and seven runs, winning, 7-1. The first-place New Yorkers, behind the hurling of veteran Spud Chandler, were paced by the hitting of Tommy Henrich, who hit a homer and two doubles. McCahan followed Scheib in the ninth, but fared no better, yielding three hits and two runs.

In his next outing, on July 2 at Fenway Park, Scheib was hit hard again, but got no decision. The big righthander yielded 11 hits, including home runs by Ted Williams, his fourteenth, Bobby Doerr, and Birdie Tebbetts, and all six Red Sox runs. Carl was yanked when he allowed a two-out triple to Wally Moses in the eighth frame. But with righthander Bob Savage on the mound, the A’s took the lead in the ninth, 7-6, when Chapman singled home McCosky. Savage checked Boston in the home half of the inning to collect the victory.

Pitching at spacious Yankee Stadium in the opener of a twin bill on July 6, Scheib was blasted again. He gave up five runs in the first inning, starting with a triple to Snuffy Stirnweiss. After a single, Joe DiMaggio clouted his eleventh homer of the season. Three more hits led to two more runs, and New York led, 5-0, before Scheib ended the inning. He gave up another run in the second and two more in the third, thanks to Yogi Berra‘s fifth homer of the year. After that, Jesse Flores and Russ Christopher held the Yanks, but the A’s lost, 8-2.

Writing for The Sporting News on June 30, 1948, Clifford Kachline reported that after Scheib lost twice to the Yankees in mid-1947, “it was learned that Charlie Dressen, clever signal-stealing coach of the Yanks, had ‘called’ every pitch made by the youngster–fast ball or curve–by the manner in which he held the ball.”

Whether or not that was true, Scheib’s confidence was affected by the two defeats he suffered at the hands of the Yankees and the shelling he took from the Red Sox. In the end, the 20-year-old started the season with three straight victories, but finished the year at 4-6 with a 5.04 ERA. For example, at Detroit on July 13, Scheib went the route in the first game of a double-header but lost to Virgil Trucks and the Tigers, 4-2. On July 20 Carl hurled four and one third innings against the White Sox in Chicago. Staked to a 4-0 lead by his teammates, he gave up four runs before Bob Savage came on to record the final out of the fifth inning. The A’s won, 7-4, but Savage got the victory. Beginning with a game against the Tigers in Philadelphia on July 26, Scheib pitched mainly in relief for the remainder of 1947.

“We didn’t have a very good team that year,” Scheib recalled in 2006, “I won three in a row and ended up four and six. It was tough winning in Philadelphia. Later in my career, I wanted to be an outfielder. I wanted to play the outfield real bad, which I thought I could do real well. But they always needed pitchers, so I suspect there’s some irony here.”

Just before Philadelphia’s spring camp opened in March 1948 at West Palm Beach, Florida, Carl, now twenty-one, married Georgene Umholtz, a hometown girl, on February 25. Georgene passed away in 1998, and Carl married Sandra Lindinger in 1999. But in 1948 the righthander rode the train to spring training, worked himself into shape for the regular season, and compiled a career-best record of 14-8 as the A’s made the club’s last serious run at a pennant while in Philadelphia.

Recalling those events recently, Scheib explained, “Now this is my opinion, but Connie Mack had a hard time getting his pitchers lined up in those years, you know, the steady starters. A lot of times he would start a pitcher, and if he didn’t win, he was in the bullpen for a while, relieving. We didn’t have specialists. We had long and short relievers. Every year that he let me start and if I lost, start again, I had fairly good seasons. You have to get regulated to pitching every four days, and you can’t do that in the bullpen. In 1948 I had a 14-8 season and in 1952 I had an 11-7 year, again when I started most of the season.

“In 1948 we had a pretty good bunch of starters, and we pitched well. We should have won the pennant, but we hit a bad streak late in September. We lost something like seven in a row, and that put us out of the race. In fact, we had to win the last game of the season to win fourth place.”

Connie Mack continued to sit on the bench and signal to his players, but as David M. Jordan observed in The Athletics of Philadelphia, the coaches ran the team. The outfield again featured Elmer Valo, Sam Chapman, and Barney McCosky, while Ferris Fain at first, Pete Suder at second, Eddie Joost at short, and Hank Majeski at third base completed the infield. With Buddy Rosar, Mike Guerra, and veteran Herman Franks, the A’s had good catching.

On the mound Phil Marchildon had arm troubles that limited him to nine wins. But the A’s rotation included Dick Fowler (15-8), who first made it with the A’s in 1941 and later served in the war; righthander Joe Coleman (14-13), who, like Scheib, came up during the war and resumed his major league career in 1947; rookie southpaw Lou Brissie (14-10), a former soldier who overcame more than twenty operations on his shattered left leg to return to the national pastime; and Scheib. Those four hurlers gave the club 57 victories en route to an 84-70 record and a fourth-place finish.

Scheib made a major contribution in 1948, starting with his opening game 4-0 shutout of the Washington Nationals at Shibe Park on April 25. He followed up with two more complete games, a 5-1 win at Washington and a 16-1 rout in Philadelphia over the White Sox. Against Chicago, Carl led the A’s hit parade with a single, a double, and a grand slam home run in five at-bats. But after his 3-0 beginning, the righthander lost close games to the Yankees in New York and the Tigers in Detroit. After four more starts with no decisions, Carl won four in a row, 3-1 over the St. Louis Browns at home, 5-2 over the Tigers away, 7-6 over the Browns away, and, on June 27, a 6-5 squeaker over the White Sox in Chicago.

Scheib compiled a 7-2 record by July, but he didn’t win more than two straight for the remainder of 1948. In September, for example, he started five times, winning three and losing two. In his last appearance of the season, on September 28 at Shibe, Carl pitched a complete game 5-2 victory over Vic Raschi and the Yankees. The loss–the first time the A’s had defeated Raschi in nine games dating to 1946–stalled the Yankees’ pennant drive and helped the Cleveland Indians hang onto first place. Carl’s performance helped the A’s finish fourth, after spending much of the ’48 season as a surprise pennant contender.

Also, the strong-armed hurler with the potent bat was hitting .324 by the end of August. Carl’s hitting tapered off in September, but he finished with two home runs and a hefty .298 average, going 31-for 104. He won two games with timely pinch hits. In the A’s final two contests, Scheib played left field, collecting one single in six at-bats. More than one sportswriter speculated on whether Connie Mack might shift the righthander to the outfield, based on his clutch hitting.

The 1949 season proved to be a different story for Scheib. After looking good in spring training, he posted a 9-12 record with an ERA of 5.12. Mack’s club slipped a notch to fifth despite an 81-73 record. The top four pitchers were rookie righthander Alex Kellner at 20-12, dependable Joe Coleman at 13-14, second-year star Lou Brissie at 16-11, veteran Dick Fowler at 15-11, and 5’6″ rookie lefthander Bobby Shantz, who showed flashes of brilliance and finished with a 6-8 mark. At the plate the A’s had the same core of solid hitters. Eddie Joost batted .263 with 23 home runs and 81 RBI while topping AL shortstops with 352 putouts. Sam Chapman hit .278 with 24 homers and 108 RBI. Pete Suder hit .267 with 10 homers and 75 RBI. No other player hit double digits in four-baggers, but Hank Majeski averaged .277 with nine homers and 67 RBI.

Scheib blanked the Washington Senators on a four-hitter at Griffith Stadium on April 22. But thereafter he experienced an up-and-down season, proving ineffective in his next four decisions. On April 27 the A’s lost to the Red Sox at Fenway Park, 10-6. Scheib gave up six runs in 4.1 innings, but rookie Charlie “Bubba” Harris was the loser. At Shibe Park on May 1, Carl lasted 3.1 innings and allowed six runs as the Nats belted the A’s, 15-9, but recruit Dick Welteroth lost it. On May 6 he started against the Tigers at Briggs Stadium, lasting only three innings. The A’s won, 5-4 in 10 innings, but his short stint meant Carl was sent back to the bullpen.

For the month of June, Scheib got no decisions in his first three appearances, but then he lost four in a row. The Pennsylvania native ended the month on a good note, hurling a complete game 7-4 victory against Washington in Griffith Stadium on June 29. The win improved his record to 3-6. In July Carl won twice and lost two games. His worst beating of the season came at Comiskey Park on July 22, when, with his club short on healthy hurlers, he pitched the distance but gave up 18 hits, eight walks, and 12 runs. White Sox righthander Randy Gumpert, who had debuted with the A’s in 1936, blanked his former club, 12-0. Still, Scheib returned to the starting rotation for August and won three straight, stopping the White Sox, 5-2, beating the Nats, 8-3, and outlasting the Yankees, 9-5.

Then Scheib lost against the Yankees in New York, 7-3, took a beating from the Browns in St. Louis, 11-3, and fell to the Indians at Cleveland in 11 innings, 2-1. Bouncing back, he won three of his last four starts. On September 20 in Philadelphia against the Tigers, Carl finished his season by working the first six innings (Brissie saved the win) of an 8-6 victory.

The rubber-armed righthander felt good about finishing the season on a high note. But after working on the family’s farm in the offseason, Carl suffered an offseason in 1950. For several years the Athletics had played well with little bench strength and no first-rate pitchers in the bullpen. The best rookie was righthander Bob Hooper, who led the team in victories with 15 while losing 10 times. But after Hooper, Lou Brissie went 7-19 with a 4.02 ERA, Alex Kellner won eight games but led the AL with 20 losses, and Bobby Shantz, in his third season, was 8-14 and 4.61. Veteran righthander Hank Wyse, who spent most of 1948 and 1949 with Shreveport of the Texas League after pitching six years for the Chicago Cubs, finished with a mark of 9-14.

To prepare for Philadelphia’s Golden Jubilee year, the club traded with the Browns to acquire third baseman Bob Dillinger, considered an excellent hitter, and flychaser Paul Lehner. The A’s brass and fans looked forward to a pennant race. But the lack of new talent finally caught up with the Mackmen, and they finished in the junior circuit’s basement with a record of 52-102. The A’s did rank fifth in batting with a team mark of .261, one point better than the .260 average of the Senators and the White Sox. But as a team, the A’s lofty ERA of 5.49 was the AL’s worst.

Two Athletics batted above .300: righthanded batting Bob Dillinger hit .309 with three homers and 41 RBI, while Paul Lehner, a southpaw batsman who often played left field, also hit .309 and added nine four-baggers and 52 RBI. But the heavy hitters included Ferris Fain, who averaged .282 with 10 homers and 83 RBI, Eddie Joost, who hit .233 with 18 homers and 58 RBI, Elmo Valo, who averaged .280 with 10 home runs and 46 RBI, and Sam Chapman, perhaps the best slugger, hit .251 but led the team with 23 homers and 95 RBI. Scheib, who batted .298 in 1948 and slipped to .236 in 1949, averaged .250.

On April 18, 1950, Carl started on Opening Day in Washington, following two ceremonial pitches by the ambidextrous President Truman, who tossed one righthanded and one lefthanded. Despite his 7-0 lifetime record against the Nats, Scheib gave up three hits, one walk, and four runs without retiring a single batter in the first inning. The A’s finally lost the slugfest, 8-7, and Carl was immediately shifted to the bullpen.

Overall, Scheib made 43 appearances in 1950, including eight starts, but he completed just one game–after finishing 15 games in 1948 and 11 in 1949. His ERA leaped to 7.12, easily his worst annual performance. On the other hand, he often pitched well in relief. Since most of his relief appearances came in the late innings, the big righthander became, in effect, the club’s “closer,” before major league teams had such a specialist.

After his opening day loss, Scheib picked up saves against the White Sox and the Indians on May 7 and 9, respectively. He continued to work out of the pen until May 23, when Connie Mack gave him a spot start in St. Louis. Carl worked the first six innings and took the loss, allowing seven hits and five runs as the A’s fell, 7-1.

Three days later, on May 26, the A’s board of directors met and announced some surprising decisions, notably that coach Jimmy Dykes would be the club’s assistant manager and would take over for Connie Mack when the season ended. Also, Mickey Cochrane, the great catcher on Mack’s pennant-winning teams of 1929, 1930, and 1931 and also the current pitching coach, was named general manager. Earle Mack, Connie’s longtime heir apparent, became chief scout. In actuality, Connie Mack’s 50-year managerial career was over, and Dykes was the new pilot.

On May 28 Scheib won his first game, hurling six innings in a curfew-shorted contest against the Yankees at Shibe Park. With Carl spacing six hits, the A’s stopped the Bronx Bombers, 6-5, a victory that improved his record to 1-3. After his next start, a 12-5 loss to the Browns on June 5, Scheib worked mostly in relief. At home on July 23, he won his second contest, 5-4, stopping the White Sox with one hit in the last two frames of a twin bill’s nightcap.

On August 2 at Comiskey Park, Scheib twirled his only complete game of the season. The A’s defeated the Chisox, 10-3, as Carl improved to 3-6. But he started and lost his next two outings, lasting just two innings in a 10-3 defeat in St. Louis and going 1.1 innings in a 7-2 loss to the Yankees in New York. His final appearance came at home on September 13, when he came out of the pen to work the bottom of the ninth at St. Louis. But leadoff batter Ken Wood homered on the first pitch, giving the Browns a 4-3 victory. Carl’s ledger fell to 3-9, and his season was over.

Connie Mack, who was eighty-eight on December 22, 1950, retained the title of club president, but no longer owned or controlled the team. The 1950 season had proven tough on the entire club. Reflecting on those years in 2006, Carl said, “I wanted to be traded so badly. I really wanted to pitch for Detroit, or for Boston. I almost made it to Detroit, but Joost was in the deal, and the A’s wouldn’t let him go. I just wanted to pitch for a better team.”

In 1951 the A’s, thanks to a late-season surge, climbed to sixth place with a 70-84 record, ranking ahead of Washington and St. Louis and three games behind fifth-place Detroit. Philadelphia was sixth in team hitting with a .262 mark. For the third straight year the A’s led the league in double plays, turning 204 (the Yankees ranked second with 190), good defensive support that helped the hurlers. Philadelphia ranked sixth in team ERA with a 4.47 mark, while Cleveland once more led the league at 3.38.

Scheib endured another difficult season in 1951, winning only once and losing 12 times. But he appeared in a career-high 46 games and recorded 10 saves, a feat that helped him earn a raise after the season. The club had four pitchers who won in double digits. Little Bobby Shantz led the team with an 18-10 mark and a 3.94 ERA. Alex Kellner won 11 games but led the league in losses with 14. Bob Hooper went 12-10 and 4.38. Morrie Martin, a southpaw who debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1949 but won 14 games for St. Paul of the American Association in 1950, enjoyed an 11-4 season with a 3.78 ERA.

Scheib spent the first half of 1951 bouncing between the starting rotation and the bullpen. His first outing came against the Red Sox at Fenway, when he worked the last 5.2 innings in a 6-5 loss. Starting three games in a row, he lost two. The Senators beat him in Washington, 6-1, and the Tigers won at Detroit in 11 innings, 9-1, but Scheib was not around at the finish of either contest. On May 9 at Sportsman’s Park he blanked the Browns on one hit over the last two innings, winning his only game of the year, 8-2.

Thereafter, the Gratz star worked mainly in relief. Pitchers who worked out of the bullpen during the 1940s and the 1950s learned that warming up two, three, four, or more times per game was not uncommon. Thus, total innings pitched hardly reflected the wear and tear on a pitcher’s arm.

Jimmy Dykes did start Scheib three straight times in late June, but Carl lost all three: 4-1 to the White Sox, 9-3 to the Tigers, and 6-5 to the Red Sox. The loss at Fenway came on July 8 in the nightcap of a double-header. Carl hit the first batter and walked the second. Dykes yanked him, and the righthander did not start again that summer. However, eight of Scheib’s saves came in August and September. His final appearance was on September 23 in Washington. He worked the last four innings in the second game of a twin bill. The A’s won, 8-3, and veteran lefty Sam Zoldak, who was 6-10 in 1951, got credit for the victory. Carl, who allowed four hits and three runs, still earned his tenth save.

“After the first couple years,” Carl recalled, “Connie Mack went to relieving me quite a lot, and that had a tendency of giving me a sore arm. Later, I had a lot of arm problems. Of course, the ball clubs didn’t know what to do about sore arms in those years. Most of the relieving happened in the beginning of a season, when Mr. Mack was trying to regulate his four or five starters.”

Scheib, a favorite of Dykes because he was always ready and willing to take the mound as a starter or reliever, trained hard and got better prepared for the 1952 season. The A’s lineup in 1952 often featured Ferris Fain at first base, Skeeter Kell (George Kell‘s brother) at second, Eddie Joost at short, Billy Hitchcock at third base, Elmer Valo in left, Dave Philley in center, and–in right–slugger Gus Zernial, acquired from the White Sox along with Philley in a trade on April 30, 1951. In that swap, the A’s gave up future star Minnie Minoso as well as Paul Lehner.

The 1952 A’s enjoyed a winning season (79-75) and climbed to fourth place, while fans enjoyed the club’s exciting hitters. Gus Zernial, tall and strong at 6’2½” and 210 pounds, batted .262, and, while he struck out 87 times, he blasted 29 homers and produced 100 RBI. Ferris Fain led the AL in hitting for the second straight year, averaging .327 with a pair of homers and 59 RBI.

The club’s biggest fan favorite was Bobby Shantz. In addition to a nifty ERA of 2.48, the 140-pound southpaw led the league with 24 victories against only seven losses, a season that earned him the AL’s Most Valuable Player Award. Combined with a good fastball and an excellent curve, Shantz sometimes threw a knuckleball. Under Dykes’ tutelage, Shantz learned to change speeds and improve the knuckler. The lefty had gone 18-10 in 1951, despite the A’s losing record.

Scheib made his own comeback in 1952, going 11-7 with a 4.39 ERA. He appeared in 30 games, started 19, and completed eight, figures reminiscent of 1948. Carl always preferred starting to relieving, and in ’52 he hurled 158 innings. Those innings pitched were his third highest, following 198.2 innings worked in 1948 and 182.2 in 1949. He enjoyed a solid spring training, his arm still felt strong, and he made a good contribution to the A’s fourth-place finish.

Carl started the season working out of the pen. In early May he won his first two games in relief, blanking the White Sox at Shibe in the last two frames of a 13-12 victory, and whitewashing the Tigers in the last 1.2 innings of a 6-5 win. But on May 8 and 11 he lost twice in relief, falling to the Browns, 9-8, and the Senators, 5-2. On June 22 Carl won his first start. Working the nightcap of a Sunday double-header, he scattered seven hits and shut out the Tigers in Detroit, 10-0.

But on July 11, after working 8.2 innings in relief of Harry Byrd, Scheib lost to the Indians in Cleveland. He yielded nine hits but took a 7-6 lead into the ninth. Unfortunately, he gave up home runs to Al Rosen and Larry Doby, with Doby’s being an inside-the-park blast off the center field wall. On the other hand, one of his highlight games came on August 12 in a 13-inning 4-3 win over the Red Sox at Fenway. Carl surrendered 10 hits but proved tough in the clutch, blanking Boston after the seventh frame and no-hitting them over the last three innings. Billy Hitchcock’s RBI single in the top of the 13th provided the winning margin, and Scheib improved his record to 7-4.

The husky righthander slipped in September, losing three of his last five starts. His worst defeat came against the hot bats of the White Sox at Comiskey, 7-1, as he hurled the first six innings and gave up four runs on six hits. But in his finale against the Bronx Bombers at Yankee Stadium, he pitched the route and won, 9-4, allowing nine hits. The biggest blast was Yogi Berra’s 30th homer in the sixth. When Carl walked off the mound that afternoon, his record was 11-7, a vast improvement over his 1-12 finish of 1951.

Despite having the league’s MVP in Bobby Shantz, the AL batting champion in Ferris Fain, and the slugging of Gus Zernial, the A’s suffered a bad year in 1953, falling to seventh place with a disappointing mark of 59-95. Jimmy Dykes later said, “By May my hopes were shattered.” Fain was traded to the White Sox for Eddie Robinson, a slow first sacker who was expected to drive in more runs than Ferris. But the pitching was subpar: Harry Byrd lost 20 games and won only 11. Mexican-born righthander Marion Fricano, a rookie at twenty-nine, posted a 9-12 record. Alex Kellner led the staff with 11 wins, but lost 12 games. After that, Shantz, who suffered arm problems, endured a tough 5-9 season, while Scheib posted a 3-7 record with two saves.

What happened to Scheib? Although once again he looked like the A’s fourth starter in spring training, he did not perform with consistency in 1953. At age twenty-four in 1951, he began having arm problems, thanks to his many mound appearances. As a result, he lost some speed off his fastball. His first outing came on April 22, 1953, when he came out of the pen to get the last out in the ninth inning against the Nats at Griffith Stadium, earning a save. Three days later Carl pitched the route but lost, 4-3, to Boston at Fenway. Afterward, he returned to relieving.

The righthander finally won his first game on May 21, also in Boston. He worked the last five innings of a 9-0 victory, allowing two hits and improving his mark to 1-1. On May 25 Scheib gave a fine performance, tossing nine innings of relief against the Senators after lefty Frank Fanovich started but couldn’t retire a batter. Carl scattered five hits and yielded a single run, but the A’s fell, 6-1. Later, on June 14, he hurled a complete game against the Browns at Sportsman’s Park, winning the nightcap of a twin bill, 3-1, and upping his record to 2-4. He won his third (and last) game against the Browns at Shibe Park on June 28, tossing a complete-game 2-1 victory and improving to 3-5.

But on July 12 in Boston, Scheib worked the fourth through the seventh innings in relief of Morrie Martin. Later, writers learned Dykes removed his righthander due to soreness in his shoulder. Carl did not pitch for two weeks, remaining in Philadelphia for treatment on his ailing shoulder while the club made a western road trip. On July 28 Dykes used Scheib at home against the Browns. He hurled 3.2 frames before leaving, again with a sore shoulder. On August 2 the A’s placed him on the 30-day disabled list. The Pennsylvania native returned for short relief stints on September 3 and 7, but the shoulder sidelined him for the rest of 1953.

Scheib went to spring training in 1954, but he couldn’t get the soreness out of his shoulder. Trying to pitch another season without the zip on his fastball, the righthander was in trouble. Former shortstop Eddie Joost piloted the A’s in 1954, and he knew about Scheib’s injury. On May 3, pitching at Shibe Park against the White Sox, Carl was hammered in the first two innings, allowing five hits and five runs en route to a 14-3 A’s loss.

Four days later the St. Louis Cardinals purchased him on a 30-day trial basis. But Carl did not receive much of a chance with the Redbirds. On May 16, working against the cross-town Phillies at Shibe, he lasted two innings, surrendering five hits and five runs in a 6-3 loss. On May 24 against the Cubs in St. Louis, he managed to retire the last two hitters in the fifth inning, but one run scored on a sacrifice fly.

The Cardinals had seen enough, and the club returned Scheib to the A’s. Carl secured his release, and a few days later he signed with Portland of the Pacific Coast League. He played four more seasons in the high minors. For the remainder of 1954, he strengthened his arm and posted a 3-3 record and a 5.31 ERA for the Bevos. Pitching for Portland in 1955, he enjoyed a 7-4 record and a solid 3.45 ERA. Sold to San Antonio of the Texas League in 1956, Carl enjoyed a very good season, going 10-5. He also hit .333 with two homers and 19 RBI. He finished his career in 1957, helping San Antonio with a 6-2 record and 3.79 ERA. But his arm was no longer strong. By the spring of 1958, Carl knew he had to retire from the game he loved.

In 2006 Scheib recalled, “I had no education, and I didn’t have a lot of choices. I worked in a store for a month. Then I leased my own business in San Antonio, a service station with an automatic car wash. I ran that business for twelve years. Later, I sold and installed equipment for the fellow who handled that car wash business. When I reached sixty-two, I just retired.”

Over the years Scheib kept in touch with family and friends and a few former teammates. On June 18, 2005, his hometown of Gratz, now with a population around 850, celebrated his career with a Carl Scheib Day. The day’s events included having the local ballpark renamed in his honor. “When I got there,” Carl said, “I was really surprised. I was overwhelmed. They put a nice, big monument up of me. People who lived there 30 or 40 years knew all about it. I’ve never had so many people come up to me for autographs. It was really a great day!”

When the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society was organized in the mid 1990s, the A’s Society invited many former big leaguers, including Scheib, to attend annual reunions. Carl enjoyed the camaraderie with former teammates and longtime A’s fans.

A good righthanded pitcher who still holds the distinction of the youngest player ever in the American League, Scheib fashioned a lifetime record of 45-65. Along the way he endured the many ups-and-downs so characteristic in the lives of big league baseball players. A temperate, modest, talented ballplayer, Carl called it a privilege to be a major leaguer. He wouldn’t trade his experiences for anything.

Talking about his career in 2006, Carl Scheib said, “The way I got to the big leagues, the opportunity I had, coming from a small town, getting a tryout from Connie Mack, I consider myself very, very lucky. I got the opportunity to learn and stay in the major leagues. I always respected my elders, but I tried to learn and do my best. Earle Brucker, our bullpen coach, helped me a lot. He would talk to me about baseball fundamentals. Those were the days when most guys wouldn’t help you, so I was lucky to enjoy such a good, long career.”

Scheib continued, “The main thing I regret was not being able to meet and thank the salesman who wrote the letter and gave me my chance.

“Looking back on my life, baseball has been good to me, pension wise, every way. In those years we loved to play the game. I thank the people who helped me, and the Philadelphia ball club for the opportunity to play in the major leagues, and the Good Lord for giving me the talent. I will always remember it as a time when guys loved to play the game.”

He died on March 24, 2018, at the age of 91.

Sources

This essay about Carl Scheib’s baseball career is based on statistics from The Baseball Encyclopedia (Macmillan, 8th edition, 1990); minor league stats from profile furnished by Pat Doyle, creator of the Professional Baseball Player Database (version 6); clippings from the Scheib File in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Library; and a variety of newspaper game stories from ProQuest, mainly for Scheib’s Philadelphia seasons from 1947 to 1954; interviews with Scheib, November 2006 and January 2007.

Full Name

Carl Alvin Scheib

Born

January 1, 1927 at Gratz, PA (USA)

Died

March 24, 2018 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.