Putsy Caballero

Aside from his colorful name, Putsy Caballero is known for being one of the youngest position players to appear in the major leagues. Despite his limited number of major-league at-bats, he participated in more than his share of baseball history. After his retirement, his exploits came to the attention of younger fans thanks to a former roommate-turned-broadcaster. He collected a trove of baseball memorabilia, only to lose it in one of the most devastating natural disasters in US history.

Aside from his colorful name, Putsy Caballero is known for being one of the youngest position players to appear in the major leagues. Despite his limited number of major-league at-bats, he participated in more than his share of baseball history. After his retirement, his exploits came to the attention of younger fans thanks to a former roommate-turned-broadcaster. He collected a trove of baseball memorabilia, only to lose it in one of the most devastating natural disasters in US history.

Ralph Joseph Caballero was born on November 5, 1927, in New Orleans, the son of Robert Caballero, a druggist, and Thelma Perrier, the daughter of a blacksmith, who died when she was young. Ralph was the fourth of five sons, one of whom died in infancy. As a boy Ralph made deliveries for his father for a quarter. The “Putsy” moniker was given to Caballero at a young age. He once told an interviewer: “Everybody down here in N’Awlins has a nickname. My brother Monroe is ‘Money.’ My brother Raymond is ‘Rainbow.’ There’s no special reason for any of those nicknames. There’s none for mine, either. People just always called me Putsy.”1

By the time he reached Jesuit High School, Ralph excelled at both basketball and baseball. He achieved all-state honors as a guard in basketball in his senior year. In baseball, Putsy was named to the all-American Legion team in his junior and senior years, and was awarded all-prep-school honors in his senior year when he led the circuit with a .448 batting average. When he graduated at 16 years old in 1944, he was offered a dual basketball/baseball scholarship to Louisiana State University.

But Ralph was not completely sold on college. That August he attended a 10-day trial with the Cubs in Nashville. Other major- and minor-league teams were also in pursuit. His high-school baseball coach scouted for the New York Giants, whose manager, Mel Ott, was also a Louisiana native. They tried to get him to sign with New York.

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, the Carpenter family had taken over the chronically underfunded and underperforming National League Phillies, and were beginning to spend money to start turning things around by signing young players and developing a farm system.2 Former umpire Ted McGrew scouted the New Orleans area for the Phillies, and recommended that they sign Caballero. The Phillies offered Ralph a contract with an $8,000 bonus — significantly more than the $2,500 or so being offered to other local players. Privately, Ott advised Caballero to take the higher offer; publicly, Ott complained about the size of the bonuses being given out by millionaires like the Carpenters and Yawkeys. Ralph’s father also advised that he sign, telling him “Putsy, if you go to college, it will take you years to save $8,000. So go ahead and sign, and you can go back to college in the offseason.”3 Putsy decided to accept the Phillies’ offer. His father drove him to Philadelphia and co-signed the contract because Ralph was a minor.

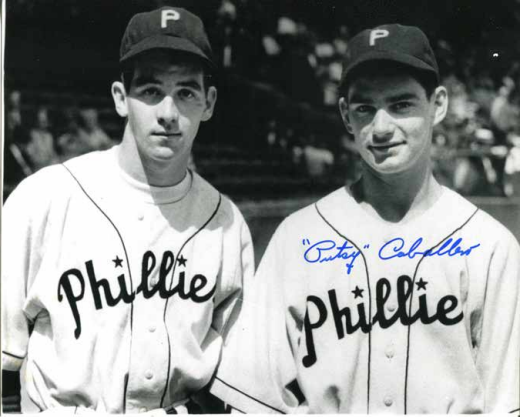

The 5-foot-9, 158-pound Caballero was added to the major-league roster right away and saw action in several games at the end of the 1944 season.4 In his debut, on September 14, he came in as a pinch-hitter and was retired by the Giants’ Bill Voiselle, then remained in the game to play third base. At 16 years, 10 months, and 9 days, Caballero became the youngest player ever to play third base, and the youngest position player to appear in the post-World War I era. “I remember ‘Fat Freddie’ Fitzsimmons, our manager, said ‘Son, go in there and play like we know you can,’” Ralph later recalled.5 In three other games that year, he got one start at third and two pinch-running appearances, but didn’t reach base in any of his three plate appearances. That offseason, he returned to New Orleans and started taking classes at Loyola University.

The next spring, the Phillies trained in Wilmington, Delaware, along with their minor leaguers. World War II had taken its toll on all of baseball, with numerous players lost to the military or vital industries.6 However, the Phillies were hit harder than most. As a result, that 1945 camp was largely made up of youngsters and players too old for military service, like 37-year-old future Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx (who himself had made the majors as a teenager) and 39-year-old catcher Gus Mancuso. When competition began for roster spots, Caballero had one advantage over his peers: At 17, he was too young to be drafted. He made the major-league club to start the season, but saw limited action in the first month of play, mainly as a pinch-runner and defensive replacement at third. By May, he was sent to the Phillies’ minor-league club at Utica, New York.

Although Putsy was the youngest player at Utica, he was not the only teenager. Pitcher Bob Chakales, also 17, was a few months older. Future Phillies teammates Granny Hamner (who had signed at the same time as Caballero) and Richie Ashburn were both 18. Nine other players were between 20 and 23. They and their teammates were playing under Eddie Sawyer, who had come over the year before from the Yankees organization. With experience as a teacher, Sawyer was a good fit for the young club. Collectively, they got a taste of professional success, winning the Eastern League pennant in 1945. It didn’t hurt that the Class-A affiliate was the highest in the Phillies’ system. “We should have been playing at Triple-A ball, but Utica was the top Phillies’ farm club, so we all played in the Eastern League and really dominated,” Caballero recounted.7 For his first full professional season, Caballero batted .279 in 130 games, and had the unusual line of no home runs and 75 runs batted in. In the field, he showed that he needed improvement, making 38 errors, all at third base.

In 1946 training camps were swelled with players returning from the service or home-front war work. The military draft was still in effect, however, and as an 18-year-old, Caballero was eligible for selection. The local draft board told Caballero’s father that if he went to spring training, he’d be at risk of being selected. The Phillies agreed to let him voluntarily retire and remain at Loyola and protect himself from the draft.8 When classes finished in May, Caballero was reinstated and was sent to Terre Haute in the B-level Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League, where he hit .283 in 76 games and had two homers. The following season he was back at Utica, where the team again won a pennant. Putsy made the league’s all-star team at second base, leading the league in fielding at that position and hitting .287. He drove in 60 runs, again without hitting a home run.

On the cusp of the 1948 season. Caballero was out of options. The Phillies decided to bring him north with the team, where he was joined by fellow rookies Hamner and Ashburn. As they had at Utica, Ashburn and Caballero roomed together in Philadelphia. The group spent much of their off-time together, and would frequent an Italian restaurant run by Sam Framo near Shibe Park. Putsy later recounted to the Philadelphia Daily News’s Paul Hagen: “I’d take [Richie] Ashburn in, [Granny] Hamner, Schoolboy Rowe. As soon as we walk in, he’d say, ‘Paisan! Paisan!’ Everybody said, ‘Man, this fella thinks you’re Italian.’ He wouldn’t let us pay for nothing. I didn’t tell him that I was French, Irish, and Spanish. That was comical. People said I should tell him. I said, ‘No, he won’t let us pay for nothing as long as he thinks I’m Italian.’.”9

His nickname also caused some confusion. Initially, the Phillies broadcasters shortened it to “Putz.” “I didn’t think anything of it ’til one day they came up to me with a stack of letters they received,” Caballero later related. “Turns out ‘Putz’ means a whole different thing in Yiddish. It meant something they shouldn’t have been saying on the air. Some listeners were offended, so they stopped calling me Putz right quick after that.10

Caballero began 1948 with a mix of pinch-hitting appearances and a few starts at second base. That changed in early May when Bert Haas, the starting third baseman, was hit by a batted ball in pregame warmups. Haas suffered a concussion and skull fracture that landed him in the hospital and kept him out of the lineup for a month. Caballero took most of the starts at third until Haas returned. Phillies skipper Ben Chapman then split playing time at third between the duo. When Chapman was fired and Eddie Sawyer took over as manager in July, Chapman gave most of the playing time to Caballero. Although he hit only .245 in 113 games and 351 at-bats with no home runs for the season, he showed outstanding defense and The Sporting News named him the top rookie third baseman.

Even though 1948 turned out to be Caballero’s only season as a major-league regular, he got to experience several events that even many longtime major leaguers never see firsthand. On July 23, he was playing third in a game at Cincinnati behind starter Robin Roberts. In the fourth inning, Roberts had walked Ted Kluszewski and allowed a single to Danny Litwhiler. The next batter, Virgil Stallcup, hit a sharp grounder to Caballero, who started an around-the-horn triple play. Then, on August 18, Caballero was playing against hard-throwing Dodger Rex Barney. When the Phillies came to bat in the fifth, Barney had yet to allow a hit. After Eddie Miller led off the inning with an infield groundout, Caballero looped a hit to center just out of the reach of Duke Snider. Barney then held the Phillies hitless the rest of the way, completing the one-hitter.

The 1949 season started for Caballero much like the previous one. He had made the Phillies as a reserve, appearing mostly as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner until he got a series of starts in June when Eddie Miller missed a short stint due to injury. By mid-July Caballero was hitting .279, but Sawyer had begun questioning his conditioning. Later that month, the Phillies shipped Caballero off to their new Triple-A affiliate in Toronto in exchange for another second baseman, Mike Goliat, who had driven in 49 runs in half a season. Caballero took the demotion hard and vowed to prove to Sawyer and the Phillies that they had made a mistake, getting back into peak playing shape and hitting .318 over his half-year at Triple A. The next spring Caballero was not initially invited to the major-league training camp. However, when Buddy Blattner, who had taken Caballero’s spot as infield reserve, retired, Sawyer called for Caballero. Still, the Phillies skipper was not ready to hand him a job. Caballero turned him around after hitting .379 in the Grapefruit League, and the Phillies opted to release Miller and go north with Goliat and Caballero as their second basemen.

Caballero’s timing was fortuitous, as the 1950 Phillies jelled into a pennant winner. Although he got only occasional starts in the infield, he appeared more regularly as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner, often taking over the basepaths for the less-than-swift players including Andy Seminick and Dick Sisler. The pennant-winning game against Brooklyn (which Caballero later recalled as his most memorable) was typical. After Seminick singled in the ninth inning of a tied game, Caballero pinch-ran for him. Caballero had attempted only one stolen base all year, but with the league championship on the line, he tried to steal second, only to be cut down by Roy Campanella. The Phillies won the game, and the pennant, the next inning on Dick Sisler’s dramatic three-run homer. In the World Series against the Yankees, Caballero came in twice as a pinch-runner. His only plate appearance was in Game Four, when he came in as a pinch-hitter and was struck out by Whitey Ford. The following winter, Caballero wrote to President Truman requesting that Ford be drafted into the military.

Caballero returned to the Phillies in 1951, beginning the year mainly as a pinch-runner and defensive replacement. It wasn’t until June 4, after getting into 16 games, that Putsy got his first plate appearance. He was able to pick up more at bats and some starts at second as the season went on, but his hitting never came around and he finished the year hitting .186. Caballero did, however, collect his only major-league home run that year — a solo shot against the Giants’ George Spencer on August 11. His final year in the majors, 1952, started similarly, with his first plate appearance coming on June 14, but his playing time continued to decrease.

Putsy played at Triple A for the next three seasons — in Baltimore in 1953 and Syracuse in 1954 and ’55. At Baltimore, he found a late-season power surge, with five home runs, including a grand slam, just one short of the number he had collected in all of his previous minor- and major-league games. He also went 2-for-4 with three RBIs in an exhibition against his old Phillies teammates. Caballero’s 1954 season was cut short due to a knee injury, but the team asked him to stay on anyway to mentor some younger players. He finished the 1955 season, but his production had dropped off.

In 1956 the Phillies had again changed Triple-A teams, this time to Miami, where Caballero was scheduled to play. In 1948 Caballero had married his childhood sweetheart, Clare Levy, and by 1956 three of their seven children had arrived. Several major-league teams expressed interest, but the Phillies would not release his contract. “[I]n those days, the team owned you. You couldn’t play out your option or contract,” Caballero said.11 Even though he was still only 27, he decided to call it a career. Although he did some scouting for the Phillies for a few years, he was ready for a new vocation.

During his playing days, Caballero had held a variety of offseason jobs including basketball official, construction worker at an aluminum plant, and department-store clerk. When it came time for full-time work, he joined the extermination business run by his father-in-law. His co-workers included former major leaguer Mel Parnell and musicians Al Hirt and Pete Fountain, who got their starts in clubs run by the Levy family. Caballero later struck out on his own as an exterminator, where he worked until his retirement in 1997.

Early in his playing career, Caballero had begun participating in charity baseball games and baseball clinics for children in southern Louisiana. He continued after his playing days ended, eventually transitioning to more of an administrative role.

Caballero also returned to Philadelphia occasionally for reunions and events commemorating the 1950 team, including the presentation of league champion rings in 1975. There he caught up with his former roommate Richie Ashburn, who had become a beloved broadcaster for the Phillies. Ashburn regularly told his listeners and readers of his newspaper column anecdotes about Caballero, recounting his exploits to those too young to have seen him play.12 In one of his columns, Ashburn wrote about Ralph’s role in the team’s regular card games, which took place during the long train trips to Western cities: “[Putsy] was the most successful gambler on the team. He claimed he made more money playing cards than baseball. Watching him play both, I believed him.”13

During his playing days, Caballero had collected a treasure trove of memorabilia, including a full uniform, an autographed photo of all of the Whiz Kids, and signed items from famous players including Joe DiMaggio, Eddie Mathews, and Pete Rose. Almost all of it was lost in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina left his home with water up to the roof line for several days. “All the baseball stuff [was lost],” Caballero said. “I had a ball from Babe Ruth in 1948, signed when he came to the clubhouse in spring training. He signed a baseball for me. That was the year that he died. I had it in a glass case, but the cover come off of it and everything else.”14 Only the uniform was salvageable, along with some photos that were with his children at the time of the storm.

Putsy Caballero received two New Orleans-area honors: first, as a 1994 inductee into the All State Sugar Bowl Greater New Orleans Hall of Fame and then as a 2009 inductee into the New Orleans Professional Hall of Fame. He rebuilt his damaged home and remained in the area until his death on December 8, 2016.15

This biography appears in “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2018), edited by C. Paul Rogers III and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Beyond those sources cited in the notes, information for this biography was derived from Caballero’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Giamatti Library, and articles from various issues of the Baltimore Sun, New Orleans Times-Picayune, New York Times, Philadelphia Daily News, Philadelphia Inquirer, and The Sporting News

Notes

1 Robert Gordon, Then Bowa Said to Schmidt … The Greatest Phillies Stories Ever Told, (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2013), 12-13.

2 David M. Jordan, Occasional Glory: The History of the Philadelphia Phillies, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2005), 93.

3 Marty Mulé, “New Orleans’ Ralph ‘Putsy’ Caballero’s 70th anniversary of a major league milestone arrives,” The Advocate, September 19, 2014.

4 When he reached the majors, Caballero was listed as 5-feet-11 and 175 pounds.

5 Rich Marazzi, “Caballero: A Major-leaguer at Sweet 16,” Sports Collectors’ Digest, June 11, 1999, 60.

6 For further information on professional baseball during the World War II era, see David Finoli, For the Good of the Country: World War II Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co.). A discussion of the Phillies during this time can be found in Seamus Kearney’s article in Marc Z. Aaron and Bill Nowlin, eds., Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2015).

7 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 125.

8 Marazzi.

9 Paul Hagen, “Putsy Caballero: He’s 82, gardens, hits the casinos,” Philadelphia Daily News, March 25, 2010.

10 Gordon, 14.

11 Mulé.

12 Caballero named one of his sons after Ashburn.

13 Richie Ashburn, “The Way We Were,” Philadelphia Daily News, September 27, 1990.

14 Hagen.

15 “Ralph ‘Putsy’ Caballero Obituary,” The New Orleans Advocate, reprinted by Legacy.com (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/theneworleansadvocate/obituary.aspx?n=ralph-putsy-caballero&pid=183073430&fhid=5630), retrieved December 17, 2016.

Full Name

Ralph Joseph Caballero

Born

November 5, 1927 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

December 8, 2016 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.