The Real First-Year Player Draft

This article was written by Clifford Blau

This article was published in Summer 2010 Baseball Research Journal

Nearly a decade before the amateur draft as we know it today, Major League Baseball instituted the First-Year Player Draft in an effort to reduce signing bonuses to prospects.

Nearly a decade before the amateur draft as we know it today, Major League Baseball instituted the First-Year Player Draft in an effort to reduce signing bonuses to prospects.

The third in a series of rules passed by Major League Baseball’s owners in an attempt to save themselves from paying large bonuses to amateur prospects, the First-Year Player Draft was in place from 1959 to 1964. Although it was often referred to as a bonus rule, it actually covered all first-year players, regardless of whether they had received a signing bonus. At first it had little effect, but, when the rules were strengthened, it took on some of the flaws of its predecessors and was soon replaced by the amateur draft.

Following the Second World War, MLB clubs found that the price of premium amateur talent was rapidly rising. Some were giving untried players signing bonuses that were in excess of the average major-leaguer’s salary. The other clubs, many of whom couldn’t afford to compete for these prospects, viewed this as a problem and demanded a solution. In response, from 1947 to 1950, and again from 1953 to 1957, Organized Baseball instituted bonus rules. These stipulated that players who had received bonuses above a certain amount had to be kept on MLB rosters after one year in the minors (in the earlier rule) or immediately (in the second rule). This hurt player development but didn’t keep teams from paying large bonuses.

At the 1958 winter meetings, the owners instituted the First-Year Player Draft. The draft was held at the winter meetings beginning in 1959 in conjunction with the Major League and Minor League (Rule 5) drafts. Initially, the rule allowed teams to draft a player who was on the roster of a team at a lower level and had just completed his first season in Organized Baseball. Major-league teams could draft players from Class AAA and lower. Class AAA teams could select players from Class AA and lower, and so on. For an MLB club, the price in the First-Year Player Draft was $15,000, to be paid to the club that the player it was drafting belonged to; minor-league clubs could draft at a lower price, which depended on their level. This was significantly lower than the Rule 5 draft price of $25,000.

Under the bonus rules of 1947 through 1957, teams were motivated to pay players under the table to avoid the restrictions of those rules. But that incentive was gone with the First-Year Player Draft, since it applied to all players, even if they didn’t receive a bonus. Clubs became reluctant to invest bonus money in a player whom another club could draft at a fixed price. Moreover, the First-Year Player Draft required that teams losing a player in the draft continue to pay him any deferred bonus. The goals of this draft were to keep bonuses down and to allow less-wealthy teams to compete for talent with the freer-spending clubs.

Thirty-nine first-year players were protected on MLB rosters that winter. Only one player was chosen by an MLB team in this initial draft, pitcher Mike Lee being taken by the Cleveland Indians, along with thirteen taken by minor-league clubs. The First-Year Player Draft followed the same rules as the major-league draft other than price, which meant the Indians had to keep Lee on their roster the full season or offer him back to the Giants. And so Lee stayed with Cleveland all of 1960, pitching only nine innings. Few teams were willing to use a roster spot on such an inexperienced player, so the draft had little effect in 1959.

The number of veteran minor-leaguers (those with at least four years of OB experience) being taken in the Rule 5 draft might have been expected to rise with the coming of the First-Year Player Draft, with fewer rosters spots available after the first-year players were protected, but it doesn’t seem to have happened. Between 1958 and 1959 the number of picks increased only from twelve to thirteen.

The following year, the requirement for MLB teams to keep first-year draftees on their roster was dropped, and the price for selecting a player in the First-Year Player Draft was changed to a flat $12,000 for all levels. As a result, the number of players drafted by MLB teams increased to six in 1960 and fifteen in 1961. There were also sixteen players taken by minor-league teams in 1960 and eight in 1961. Of these 45 players, only one, Jim Merritt, became a star. The low price allowed teams to take long chances on players such as William Maddox, who was 0–11 with an 8.50 ERA in his first professional season, yet was picked by the Yankees in the 1961 draft. Likewise, Steve Cosgrove was taken by the Orioles from the Braves despite an 0–9, 7.35 record in Class D. Those investments rarely paid off.

The first-year player rule was still not strong enough to fully moderate bonuses, so some teeth were added to it in 1962. The draft price was lowered to $8,000 for all teams. More important, a new restriction was applied. With one exception per team, first-year players added to the 40-man roster to protect them from the draft could not be optioned to the minors. Furthermore, the one option teams were allowed (the designated assignment) had the effect of reducing the size of their active roster from 25 to 24 for the bulk of the season. If teams wanted to send additional first-year players to the minors, they had to obtain waivers from the other MLB clubs, who could claim each player at the same $8,000 price applicable to the draft. To further encourage drafting, teams with a full 40-man roster were allowed to select one first-year player, although they were not permitted to take anyone in the Rule 5 draft. These changes had the desired effect, at least in the most visible way. The number of first-year draftees selected by MLB teams jumped to 45 in 1962 with an additional 33 picked by minorleague clubs. Among them were such future stars as Glenn Beckert, Paul Blair, Dave May, Lou Piniella, and Jim Wynn.

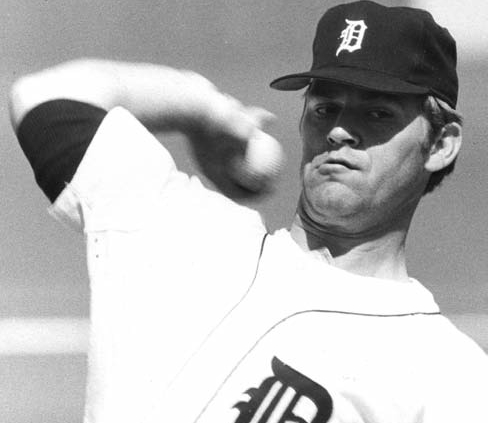

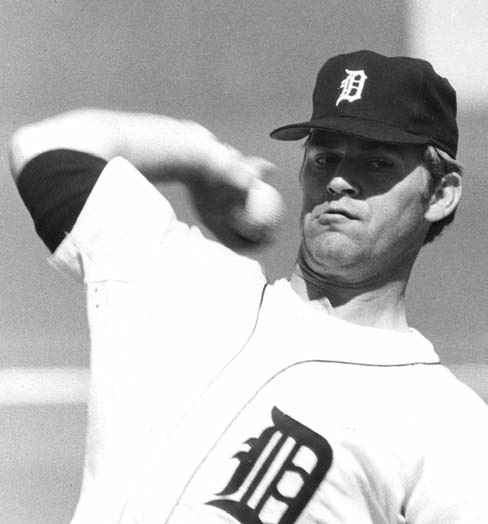

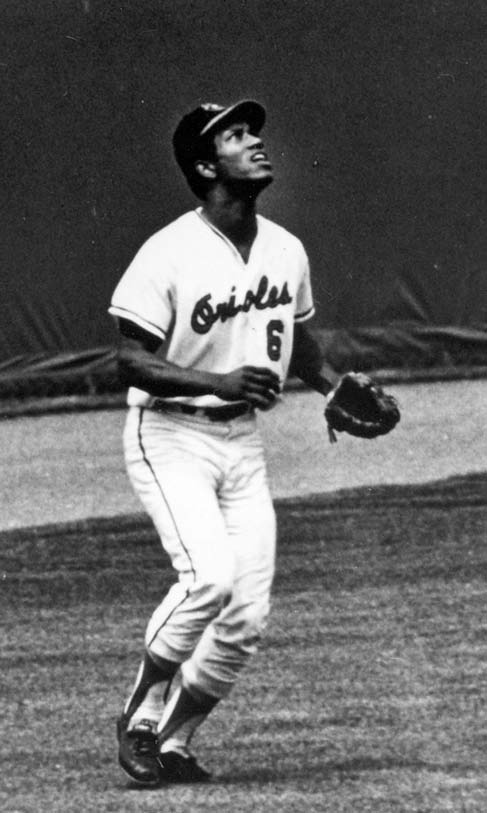

In addition, MLB teams were carrying an average of five first-year players on their winter rosters, up from 2.5 per team in 1959–60. Among those who didn’t make their team’s 25-man roster and were lost to other clubs via waiver claim was Denny McLain. The 1963 Yankees, defending their championship, started the season with a first-year player, Curt Blefary, in the minors on a designated assignment. They decided in mid-season that they couldn’t afford to use a roster spot on him and placed him on waivers. He was claimed by the Baltimore Orioles, and a couple of years later was AL Rookie of the Year, and then helped them to the 1966 world championship, along with first-year draftee Paul Blair. Meanwhile the Yankees sank to last place.

The biggest complaint about the rule was that it penalized clubs that did a good job of signing and developing new players. Fresco Thompson, farm director of the Dodgers, claimed that 200 fewer amateurs were signed to contracts by Organized Baseball in 1962 than the year before because of the risk of losing those recruits after one year. That was enough to stock ten minor-league teams.

The number of players taken in the 1963 draft was 52 by MLB clubs and 16 by minor-league squads. Some of the top names were Reggie Smith, Bobby Tolan, Rudy May, Dick Bosman, and Luke Walker. The most recent expansion teams, the Senators, Angels, Mets, and Astros, were hampered in their efforts to build with youth, since they were having to keep inexperienced players on their benches rather than let them develop in the minor leagues. In recognition of this, the other teams voted in December 1963 to allow them, in addition to the one designated assignment, to option four first-year players without waivers or counting against the 25-man roster.

As for whether the rule was achieving the goal of reducing bonuses, there is evidence to suggest it succeeded. Gabe Paul, general manager of Cleveland, claimed in 1964 that annual bonuses had gone down from $7 million before the draft was instituted to about $4.5 million in 1963. Other insiders such as Ed Short and Hal Keller agreed that the rule was effective in reducing bonuses. However, the conditions that led to escalating bonuses still existed—namely, competition both from within Organized Baseball and from other sports. So, some clubs would still pay ever increasing bonuses to recruits such as Rick Reichardt and Bob Bailey. Rather than let a promising youth go to their competitors, they were willing to gamble that he would play at the major-league level in his second professional season. The rule may have led to the escalation of bonuses for the top prospects, while the run-of-the-mill amateur got less.

As for whether the rule was achieving the goal of reducing bonuses, there is evidence to suggest it succeeded. Gabe Paul, general manager of Cleveland, claimed in 1964 that annual bonuses had gone down from $7 million before the draft was instituted to about $4.5 million in 1963. Other insiders such as Ed Short and Hal Keller agreed that the rule was effective in reducing bonuses. However, the conditions that led to escalating bonuses still existed—namely, competition both from within Organized Baseball and from other sports. So, some clubs would still pay ever increasing bonuses to recruits such as Rick Reichardt and Bob Bailey. Rather than let a promising youth go to their competitors, they were willing to gamble that he would play at the major-league level in his second professional season. The rule may have led to the escalation of bonuses for the top prospects, while the run-of-the-mill amateur got less.

In 1964, the number of draft picks reached a high of 59 by MLB teams, with another twenty going to minor-league clubs. The best-known players taken were Felix Millan, Sparky Lyle, Ed Herrmann, and Ellie Rodriguez. In addition, the A’s lost Joe Rudi on waivers when they tried to send him to the minors. Later in the year they reacquired him by trade.

The requirement to protect first-year players from the draft negatively impacted some teams. The defending world-champion Los Angeles Dodgers in 1964 could carry only 24 players, including first-year bench warmers Jeff Torborg and Wes Parker, which left them shorthanded as they struggled to a 24–31 record in one-run games. This was one factor in their fall to sixth place. Meanwhile, the Philadelphia Phillies, who led the National League much of the season before a late-season collapse, carried little-used Johnny Briggs and Rick Wise all year. Sometimes a team could be helped by the rule inadvertently. Those same Dodgers in 1964 could not keep reliever Larry Sherry because of the roster limits and so traded him to Detroit for minor-league veteran Lou Johnson, who became their regular left fielder and a World Series star the following year.

Thanks to the tougher restrictions in place from 1962 through 1964, there was increasing dissatisfaction with the rule. Following the 1964 draft, the owners decided to do away with the first-year draft. The requirement for all but one first-year player to pass through waivers before being sent to the minors was kept in 1965, although that designated assignment would no longer reduce the 25-man roster. The draft was replaced by an amateur draft (which has lately been called the First-Year Player Draft, oddly enough). They also made all minor leaguers not on an MLB team’s 40-man roster eligible for the Rule 5 draft. However, since some teams felt this would penalize those who had chosen well in the amateur draft, players who had been selected in the June draft or who signed after that would not be eligible for the Rule 5 draft until after their second season in professional ball. Interestingly, these individuals were still officially designated as “first-year players” in the rules and were still available for the special $8,000 price. After 1968 the drafting of players with one or two years’ service in Organized Baseball was phased out.

Many players saw their careers affected by the First-Year Player Draft. Most obvious were those who were taken in the draft. However, other players were affected less obviously. Some got a chance to see major-league action two or three years earlier than they might have otherwise, because they were being protected from the draft. A lot of these saw limited action, such as Mike Kekich and John Sevcik. Outfielder Ross Moschitto, kept on the 1965 Yankees at the age of 20, appeared in 96 games without a single start. However, others got a fuller chance and took advantage of it, most notably 19-year-olds Tony Conigliaro and Wally Bunker in 1964. Lou Brock and Rollie Sheldon also fell into this category. Still others— Ron Hunt and Ken Hubbs, for example—were added to 40-man rosters early and so may have reached the majors sooner than they would have without the FirstYear Player Draft. Of course, while youngsters were helped, there were fewer roster spots available for veterans. For example, Dale Long performed well in spring training with the Cubs in 1964, but they decided not to keep him, since they were protecting two firstyear players on their 25-man roster, bringing his career to an end.

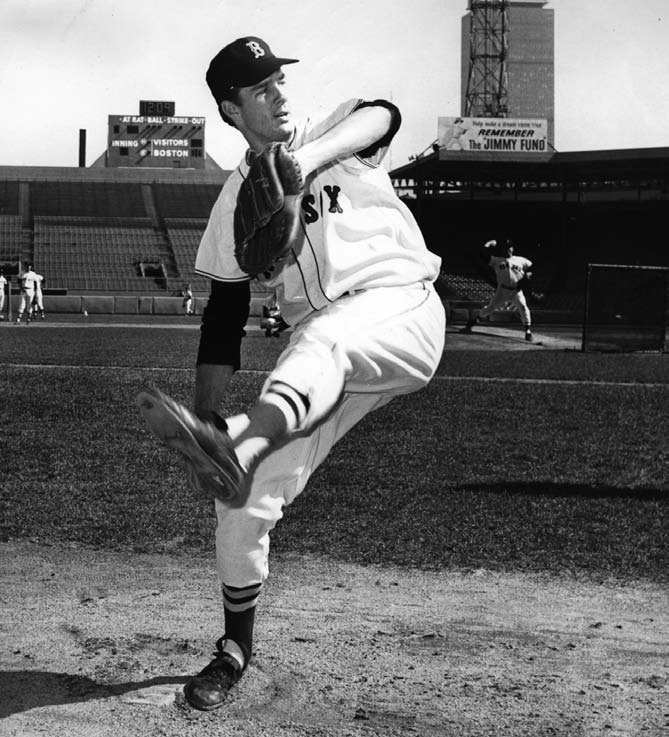

Many players saw their careers affected by the First-Year Player Draft. Most obvious were those who were taken in the draft. However, other players were affected less obviously. Some got a chance to see major-league action two or three years earlier than they might have otherwise, because they were being protected from the draft. A lot of these saw limited action, such as Mike Kekich and John Sevcik. Outfielder Ross Moschitto, kept on the 1965 Yankees at the age of 20, appeared in 96 games without a single start. However, others got a fuller chance and took advantage of it, most notably 19-year-olds Tony Conigliaro and Wally Bunker in 1964. Lou Brock and Rollie Sheldon also fell into this category. Still others— Ron Hunt and Ken Hubbs, for example—were added to 40-man rosters early and so may have reached the majors sooner than they would have without the FirstYear Player Draft. Of course, while youngsters were helped, there were fewer roster spots available for veterans. For example, Dale Long performed well in spring training with the Cubs in 1964, but they decided not to keep him, since they were protecting two firstyear players on their 25-man roster, bringing his career to an end.

It is well known that MLB’s amateur draft is a crap shoot, with many high draft picks never meeting expectations or even advancing to the majors. The difficulty of projecting young ballplayers is illustrated by the lack of success of many of the players taken in the First-Year Player Draft. Overall, there were 178 players chosen by MLB teams and 106 selected by minor-league clubs. Of those, only 67 and seven, respectively, ever played in MLB, and only 50 achieved either 300 plate appearances or 50 innings pitched.

Naturally, some clubs gained an advantage from the First-Year Player Draft, while others were hurt. Perhaps no team was helped more than the 1967 Boston Red Sox. Regulars Reggie Smith and Joe Foy were both obtained via the draft, along with early-season starting pitcher Bill Rohr and reliever Sparky Lyle. In addition, a couple of the team’s biggest stars, Tony Conigliaro and Jim Lonborg, benefited from the early look they got as a result of Boston’s desire to protect them from the draft.

The First-Year Player Draft was another unsuccessful attempt by Major League Baseball to reduce signing bonuses to amateur prospects. It was replaced by the amateur draft, which is still in place more than forty years later. While it was in effect, though, it had a big effect on the teams and players of Major League Baseball.

CLIFFORD BLAU, a retired CPA living in White Plains, New York, is a frequent contributor to SABR publications.

Sources

Chicago Tribune

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Retrosheet

Nowlin, Bill, and Dan Desrochers, eds. The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox. Burlington, Mass.: Rounder Books, 2007.

Major League Rules and Major–Minor League Rules.