The Retroactive All-Star Game Project

This article was written by Chuck Hildebrandt - Mike Lynch

This article was published in Spring 2015 Baseball Research Journal

It’s the top of the 10th inning, and there is one out in this hotly contested All-Star Game. A runner is on third by way of the triple, another on first via the intentional walk, but now the pitcher has this batter on the ropes with a 2–2 count. The crowd is evenly split between National League and American League partisans, and as the Senior Circuit pitcher stares in toward his catcher, the Junior Circuit batter waits tensely on the delivery, preparing to respond to whatever is offered.

As Midsummer Classics go, this one has been a doozy.

The runner dances off third as the pitcher gets his sign, goes into the set, waits a couple of beats … then quickly delivers a low outside fastball that the right-handed hitter pulls deep into the hole to the right of the shortstop, Rabbit Maranville, who backhands the ball and one-hops the throw to his first baseman, Hal Chase—alas, a step too late to get the out. And so Ray Chapman gets his single, moving Wally Pipp to second and scoring Tris Speaker from third, and ex-Buf-Fed hurler Fred Anderson is now on the hook for the loss for the Nationals, which finally does come to pass as Anderson himself strikes out in the bottom of the frame to end the contest and hand the Americans a 5–4 victory on this warm and rainy July Friday at the Polo Grounds.

At this point, you, the “knowing Fan,” might have simultaneously snapped your neck, blinked hard, and stared into the preceding paragraph asking yourself, “Wait, what? Rabbit Maranville? Hal Chase? Ray Chapman, Wally Pipp, Tris Speaker? These guys were never in the All-Star Game, were they? And who the heck is Fred Anderson, anyway?”

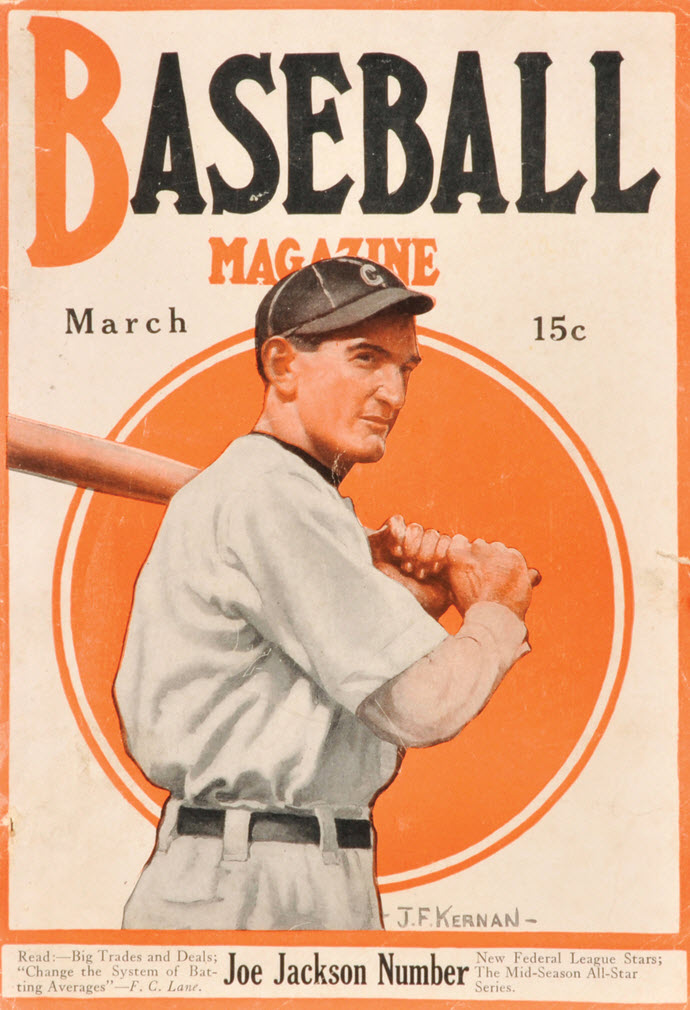

And you’d be right: They never were in a real All-Star Game, because we all know that the first one wasn’t played until 1933 at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. But it was not for lack of the All-Star Game idea to ever come up in the first place, for it did as early as 1914, in a series of articles in the popular monthly Baseball Magazine. So it might have happened. And with the help of some modern-day innovations, we did make it “happen,” using a combination of the most comprehensive baseball stats website on the planet, a simple-to-use online survey website, and one of the very best game simulators on the market.

But the best thing you’ll learn from this article is that, as much fun as it was to play the games out and to see those results unfold, it was uncovering an unexpected insight into the legacy of the stars from that era that surprised and delighted us the most.

INCEPTION

The idea for the Retroactive All-Star Game (RASG) project first occurred to Chuck Hildebrandt in February of 2013, when Baseball-Reference.com (B–R) added splits back to the 1916 season in their excellent Play Index.1 Included within the new feature were the standard half-season splits, and the idea of putting together All-Star rosters based on first-half stats immediately leapt to Chuck’s mind. He jotted down this project idea and set it aside.

About a year later, thumbing through an old Baseball Research Journal, Chuck came across an article written by Lyle Spatz about retroactive Cy Young Award winners, and later, an online article Lyle wrote about retroactive Rookie of the Year awards, both going back to 1901 and featuring winners chosen by SABR member vote.2, 3

Reminded of his own idea, Chuck googled around online to see whether there was a record of anybody ever having undertaken anything like a retroactive All-Star game project, or having written an article about the idea. Outside of threads existing in various online forums, he didn’t find anything like this specifically, but during his research he did find that between late 1914 and early 1916, Baseball Magazine had advocated for a midseason All-Star game (or more exactly, an All-Star series). The timing of the magazine articles lined up well with the availability of the splits data back to 1916 at B–R, and now there was a plausible historical context to support the idea. This all struck Chuck as kismet, and so the impetus to go forward with the RASG project was born.

The next several sections provide a great amount of detail about how the project was developed and managed. If you’re not so interested in how the sausage was made, feel free to skip ahead to the section labeled “Topline Results” below. However, if you’re a process nerd as the authors are, then here you go!

GROUNDWORK

The first thing Chuck wanted to find out was, just what had been said about the All-Star concept before the actual games were launched in 1933? He reasoned that if there were a way to tie in this project to what had actually been said or written about the topic, it would make the premise seem all the more historically plausible.

The first thing Chuck wanted to find out was, just what had been said about the All-Star concept before the actual games were launched in 1933? He reasoned that if there were a way to tie in this project to what had actually been said or written about the topic, it would make the premise seem all the more historically plausible.

Baseball Magazine published four separate articles about the possibility of an All-Star Series. The articles’ timing of 1914 through 1916 was a great coincidence, since the splits data featured went back to 1916, creating a credible natural starting point for the first games of the project.4

At the time the articles were written, the choosing of all-time All-Star teams (referred to by the magazine as the “All America Baseball Club”) was considered a “universal fad,” and one article cites efforts by Spalding’s Record to assemble All-Star teams (which they termed “National All-America” teams) covering five-year periods from 1871 on, culminating in a final All-Star (“Grand National All-America”) team for the whole of baseball history through then-present day 1913.5

But the idea of playing actual live contests between “All-Star” teams consisting of the greatest players of the current time first appeared in the magazine in 1915, which the authors presciently envisioned as occurring midseason to slake the fans’ thirst for determining which league was the better one even before the “World’s Series” in the fall pitted both leagues’ top teams against each other. The article also argued that a midseason All-Star series would “stimulate [fan] interest [and] vary the monotony of a long stretch of 150 games,” the latter of which they deemed to be “a serious handicap,” and which would also “advance the reconstruction period” following “two years of wanton destruction” wrought by “the Federal League war.”

The magazine went on to claim that an All-Star series would even provide something a World Series between two great but still flawed teams could not: “the best baseball the game can offer,” even going so far as to maintain that such a Midsummer Classic would “represent a perfect baseball series under as nearly ideal circumstances as possible.”6, 7

It’s interesting that the articles that influenced the RASG project specifically called for an All-Star series, versus a single game. Originally, the proposal was for a seven game series, “a single week’s work,” and preferably to be played in New York, Boston, or Chicago in order to best handle the large crowds they believed such a series would generate, believing it would spark so much interest that “a man might well journey from the Pacific Coast” to take it in.8

The magazine justified the idea of a weeklong series by maintaining that regular season schedules would still proceed uninterrupted, and that the stars would simply vacate their teams for the week to play in the All-Star series while their regular teams continued to toil.9 This proposal was the main reason the decision was made that our Retroactive All-Star contests would at first start out as a series, and an educated guess was made as to how it might evolve from there. (It was imagined that several owners, especially those in the heat of a pennant race, would have objected to losing their stars for a whole week at a stretch, and that a compromise of a three-game series would have been reached to mollify their concerns and secure their support.)

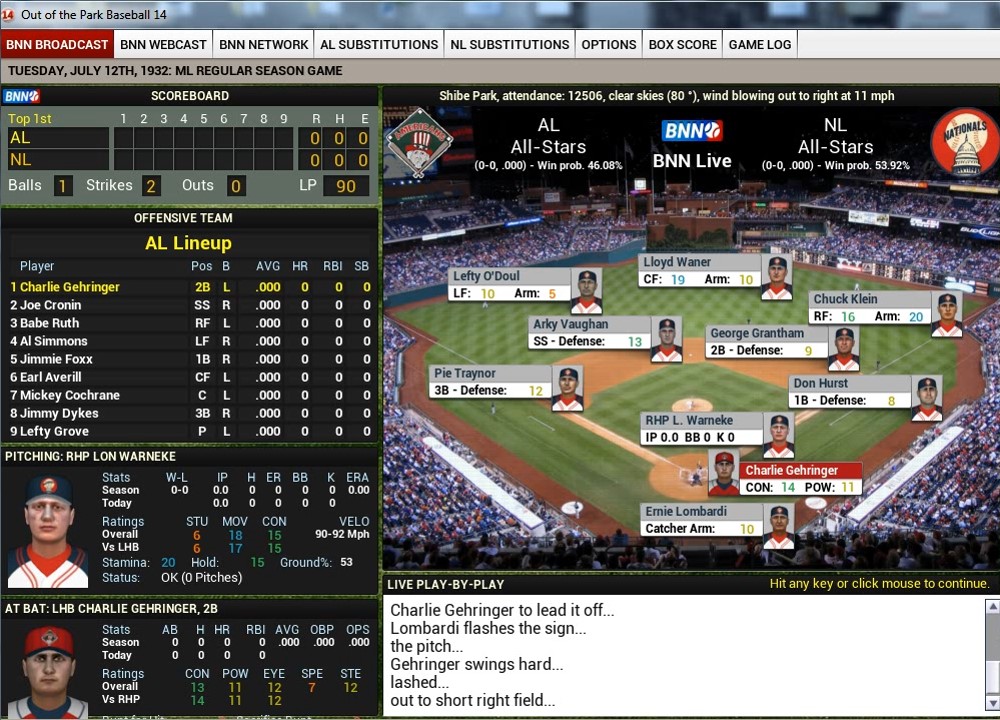

Next, Chuck sought a partner to “sim” the games, someone who was already an expert at doing so. He put out the call for a sim partner on the SABR-L listserv, and out of several responses agreed to work with Mike Lynch, proprietor of the website Seamheads.com. Mike is an expert at using the Out of the Park (OOTP) game simulator, generally considered the most advanced baseball management simulation game available at the time of this project. It is also great good luck that Mike happens to be the proprietor of a popular and terrific historical feature website, and he was willing to write up game accounts and publish them on the site as the project evolved.

PROJECT DEVELOPMENT

With the partnership in place, and having established that the RASG would start with a three-game series during the 1916 season, the project details started coming together. Voting for All-Star starters would be conducted using SurveyMonkey.com, a website that allows ordinary people to field online surveys and polls. SABR also uses SurveyMonkey to conduct its own polls, and again as luck would have it, SABR generously offered to share its account to allow us to conduct the voting for the RASG project. After the voting for a season’s All-Stars was to be completed, the reserves would be manually selected to fill out the rosters, which would then be sent to Mike to sim the game using OOTP 14, the latest available version of that game at the time.

With the partnership in place, and having established that the RASG would start with a three-game series during the 1916 season, the project details started coming together. Voting for All-Star starters would be conducted using SurveyMonkey.com, a website that allows ordinary people to field online surveys and polls. SABR also uses SurveyMonkey to conduct its own polls, and again as luck would have it, SABR generously offered to share its account to allow us to conduct the voting for the RASG project. After the voting for a season’s All-Stars was to be completed, the reserves would be manually selected to fill out the rosters, which would then be sent to Mike to sim the game using OOTP 14, the latest available version of that game at the time.

Mike had been using OOTP to simulate games for almost 15 years and, as a big fan of the game, understood how the plethora of features it offered made it the right choice for this project. The ability to import historical seasons with ease and pinpoint accuracy (for example, roster sizes, strategic tendencies, and league stat totals are realistically reflected for each year), and also to easily manipulate rosters, kept setup and implementation time to a minimum. Employing the game’s unique set of features to best effect, Mike was able to easily customize the simulated games for the Retroactive All-Star Project with minimum effort but also maximum accuracy, all the way down to stadium configurations and their ballpark factors.

Because of the many options available in OOTP, Mike could set up each All-Star Game to be managed by the game’s artificial intelligence engine, which eliminated any bias he himself might have inadvertently brought to play-calling during the game, while maintaining control of substitutions, an important aspect given the requirement to pull pitchers after three innings (or sooner if necessary), as well as to make the frequent pinch-hitting and defensive substitutions needed to accurately represent the unique in-game dynamic that typifies an All-Star Game.

The process of selecting venues for the game posed an interesting riddle. To reflect a real-life likelihood, we wanted to ensure that the game would be spread among the parks of the major-league teams, but without occurring too close in time to when those same clubs hosted their actual first All-Star games. It was decided to host the inaugural RASG series in Chicago’s Comiskey Park, where the first All-Star game had been hosted in real life, and to alternate home-team status between leagues, as is done today.

To select locations for subsequent All-Star contests, we reviewed real-life actual All-Star Game venues for the first 20 or so years in history, in order to obtain a fair spread between the years a team hosts the games in its venue and make it equitable among all the franchises in the majors. Since the RASG was conducted in 16 separate seasons (we imagined that Retroactive All-Star contest would have been canceled for war during the 1918 season in RASG, as it had been in 1945 in real life), that created a neat situation in which each of the 16 major-league teams could host a RASG once each, with the spread between their first (RASG) game and their next real-life game ranging between 10 and 27 years, the fairest spread we could manage.

RASGs were also awarded to clubs who had recently expanded their ballparks in real life, including Chicago’s Cubs Park (1924), the Athletics’ Shibe Park (1925), the Cardinals’ Sportsman’s Park (1926), and the Reds’ Redland Field (1928).

(Note: The 1932 RASG game was awarded to the Phillies, who we imagine would have arranged with the Athletics to host the game at spacious Shibe [33,000 capacity], as their own Baker Bowl [18,800 capacity] would have been deemed too tiny at the time.)

VOTING/SELECTION PROCESS

The first step in setting up the RASG voting structure was to download the first-half stats for each player, for each year 1916 through 1932, and export them into an Excel spreadsheet, from which we could then format and post the stats for each team’s starters onto the RASG ballot. Batters were, of course, listed with one set of stats; pitchers with another set. (Interesting tidbit: Even as late as the 1930s, the RBI was still not a commonly reported stat, even though it had become an official stat in 1920.10 For example, when the Chicago Tribune published major-league averages during the season, they did not start including RBIs in the table until 1931.11, 12 Given this historical reality, players’ RBIs were not included on the RASG ballots.)

Next, we created a poll for each RASG on which we posted the candidates for each position in each league, with their first-half stats. The regular starters for each team were included on the ballot as long as they satisfied a minimum number of plate appearances (100) or innings pitched (77), which would have defined them as their teams’ starters and thus tracks logically with how players are listed on All-Star ballots today. This created seemingly (and entertainingly) absurd situations in which players having terrible seasons ended up on ballots, such as A’s right fielder Bill Johnson in 1917 (hitting .173 with only six runs scored); Indians catcher Steve O’Neill, also in 1917 (.179 average, no homers or steals); and Cubs shortstop Clyde Beck in 1930 (a .232 hitter during a year in which the entire league batted .303).

But, as long as a player satisfied the aforementioned minimums and was his team’s primary player at the position, he appeared on the ballot. Exceptions: pitchers with obviously terrible won-loss records were excluded, as long as there were teammates who had better records that could be listed. (Spoiler alert: None of the three players mentioned above was voted in as starters.)

Concurrently, we developed a “marketing plan” to stimulate voting interest, which called for promotional text written in the parlance of the times to be included in emails posted through SABR-L, posts in the This Week in SABR email newsletter, on the SABR website, and on each of the 30 MLB team blogs hosted by SBNation.com. We also benefited initially from a blog post and front page appearance on B–R, which led to over 1,000 votes cast in the very first RASG.

By the third RASG, it finally dawned on us to maintain an email opt-in list so we could contact confirmed voters of previous RASGs, to remind them to both vote in the new RASG and to read the results and game accounts posted at Seamheads.com after the games were simmed and written up by Mike. This plan led to nearly nine thousand votes being cast throughout the life of the project.

The voting for each RASG began on a Friday and ran for two weeks, and included an initial announcement and two reminders to vote for that RASG. After the fourteenth and final day of voting, the ballot for that season’s RASG ended and the ballot for a new season’s RASG began, both as scheduled. Once a ballot ended, Chuck tabulated the votes to determine the eleven elected starters (one position starter plus three pitchers for each team) for each squad, and then each team’s reserves were selected based on the most logical circumstance reflecting vote totals and/or first-half stats.

In a nod to real-life situations, before submitting rosters, Chuck would review the list of elected starters against B–R’s terrific Defensive Lineup tool, which reports the starting lineup fielded by each team for each game played every season since 1914.13 The goal was to make sure that the starter who was voted in for that game was not injured and out of his team’s lineup in real life, thus rendering him unable to play even a simmed All-Star game that day. If a voted starter was indeed injured, he would be replaced by the next logical candidate, usually the player who received the second most votes.

In one case, the Yankees’ Bob Meusel was elected as the starting left fielder to the 1926 RASG, but in real life he had broken his left ankle sliding into a base in late June, putting him out for six weeks.14 Since the RASG for that year was scheduled for July 13, Meusel could not have conceivably played the game, so the Senators’ uninjured Goose Goslin was chosen to replace him.

In another more colorful incident, AL starting catcher-elect Bill Dickey had to be replaced on the 1932 squad as, at the time of that year’s RASG, he was in the process of serving a 30-day suspension arising from a Fourth of July donnybrook during which he slugged Senators runners Carl Reynolds, who’d bowled him over at the plate, breaking Reynolds’s jaw in two places.15 The comparatively saintly “Black Mike” Cochrane of the Athletics was selected to replace Dickey in that ’32 affair.

As it so happened, in the majority of RASGs, there was at least one starter voted in who would not have been able to play that day because of injury or otherwise; the 1922 RASG saw four injured elected starters who needed to be replaced in this fashion.

Once this part of the process was completed and the entire roster was assembled, it was sent along to Mike so he could sim the game. At the same time, voting for the next RASG would have commenced and this voting/selection process would repeat itself.

SIMMING THE GAMES AND WRITING UP THE RESULTS

Once Mike received the roster for a year’s RASG, he would begin the simming process by creating a new historical league in OOTP corresponding to the season in which that game was to take place. For the 1921 game, for example, he imported OOTP’s 1921 season, including all 16 major-league teams and their actual rosters. He would then manually add a team to each league called “All-Stars,” to be populated with players who’d been elected or selected to that league’s All-Star team.

After selecting the OOTP options appropriate to the season being played—roster sizes, injuries, rules reflecting the era, etc.—Mike would transfer players from their regular teams to their league’s All-Star team. Once the rosters were filled, Mike would create starting lineups and depth charts based on RASG voting by the “Knowing Fan.” Batting orders would be constructed contingent upon where the players batted in their regular team’s actual order, the handedness of the batter, and where his particular set of skills would be most useful during the game.

The top vote-getters among pitchers got their All-Star team’s starting assignment, with the remainder being used as relievers. During the game itself, Mike would actively perform the role of manager for both teams only when it came to substitutions; otherwise, he allowed OOTP to manage in-game strategy itself: calling for steals, employing the hit-and-run, issuing intentional walks, etc. Substitutions would be made based on the inning, score, situation, and player’s OOTP skill ratings. For example, a slugger with a poor glove would most likely pinch-hit early in the game, while a player with a good glove would typically be used later and stay in as a defensive replacement. Such decisions were emblematic of the level of realism we sought to inject into the project.

Once the games were played, Mike would carefully review the box scores and game logs so he could write the game accounts accordingly, simulating as closely as possible the writing style used by newspapermen of that era, and post the stories to the Seamheads website.

TOPLINE RESULTS

The first three-game Retroactive All-Star series was played during the weekend of July 14–16, 1916, with the American League hosting the Nationals at Comiskey Park at the corner of 35th Street and S. Shields on Chicago’s South Side. The Junior Circuit took the first game, 4–0, as none other than Walter Johnson and Babe Ruth dominated the Nationals from the mound, but then the Seniors stormed back to take the next two games, 6–3 and 4–2, to win the set. In a series featuring 13 eventual Hall of Famers, including nine on the American side, the linchpin of the Nationals’ series victory was Giants right fielder Dave Robertson, who went 7-for-12 and scored four of the NL’s 10 total runs, including the game-winner in the pivotal Sunday rubber match.

The first three-game Retroactive All-Star series was played during the weekend of July 14–16, 1916, with the American League hosting the Nationals at Comiskey Park at the corner of 35th Street and S. Shields on Chicago’s South Side. The Junior Circuit took the first game, 4–0, as none other than Walter Johnson and Babe Ruth dominated the Nationals from the mound, but then the Seniors stormed back to take the next two games, 6–3 and 4–2, to win the set. In a series featuring 13 eventual Hall of Famers, including nine on the American side, the linchpin of the Nationals’ series victory was Giants right fielder Dave Robertson, who went 7-for-12 and scored four of the NL’s 10 total runs, including the game-winner in the pivotal Sunday rubber match.

The 1917 series was played in New York at the Giants’ Polo Grounds, in which the American League returned the favor to the National League and took two games out of three, with the first-ever RASG home runs hit by Phillies slugger Gavvy Cravath and Cubs keystone sacker Larry Doyle. Notable in this series was the falling attendance throughout: from over 38,400 in Game One, to about 33,400 in Game Two and all the way down to well under 28,000 for the final tilt, it was becoming clear that All-Star fatigue was defeating the gate over time.

After the All-Star proceedings were canceled in 1918 due to World War I, the Retroactive Midsummer Classic was reduced to a single game in July 1919 and played at the Red Sox’ Fenway Park in Boston, where the Seniors dumped the Juniors, 4–3, the former holding off a ninth-inning rally by the latter, stranding the tying run in the person of hometown shortstop Everett Scott on third base.

The Retroactive All-Star Games continued on through the Roaring Twenties and on into the early Depression years until the game returned once again to Comiskey Park for the 1933 “real” All-Star Game, featuring the real-life exploits we know so well today. But there were also several heroic moments that occurred during the simmed Retroactive games as well:

- Guy Morton and Hippo Vaughn each threw six scoreless innings against their star-studded opposition in 1916 and 1917, respectively.

- Ray Chapman went 5-for-5 in Game One of the 1917 series, a record that would have held up through at least 2015.

- Ken Williams became the first player to homer twice in a game in 1923; Chuck Klein replicated this feat in 1930.

- Eddie Collins set a record with four runs scored in 1925, and Earle Combs did the same with five RBIs in 1929, both of which would still be tied for the all-time record as of 2015.

- Dazzy Vance “Carl-Hubbelled” the Americans in 1927, fanning five of the 12 batters he faced, all Yankees and three of them Hall of Famers (Gehrig, Lazzeri, and Ruth twice, adding Meusel for good measure).

- Eddie Collins dominated his competition throughout his RASG career by going 15-for-35, plus six walks, in 13 games that included two doubles, a triple, a home run, and eleven runs scored, resulting in a scorching slash line of .429/.512/.629, the best for any All-Star with over 40 plate appearances, real or retro. (Closest: Ted Williams, .304/.439/.652 in 46 at-bats.)

For a complete listing of retroactive All-Star Game results, click here or see the table below.

THE UNEXPECTED INSIGHT

As interesting as the results of the simulated games and players’ performances might be—or might not be, more likely, even for most serious baseball fans—the more interesting, and initially unexpected, insight we took from this project might very well be the idea of how players may have been viewed very differently than they are today, if they could have included any number of All-Star Games on their playing résumés, but simply never had the opportunity.

For instance, what if a very good player who finished his career before the first actual All-Star Game in 1933 had played several All-Star Games before that, if such games had been played as far back as 1916? Would we rate him significantly higher than he really is today? Or, what if a player who played in the first few real All-Star Games toward the end of his stellar career had instead played in a whole slew of them, had they existed during the prior seventeen seasons? What would be the effect on his legacy?

And perhaps most interestingly, who are some of the players we practically never give a first thought to, let alone a second thought, that we would regard much more highly had they played or even started several All-Star Games between 1916 through 1932, since they were among the best players at their position in their league at the time?

In considering the effect that playing many All-Star Games has on a player’s legacy, we believe that the best proxy for determining how good or great his career is involves the Hall of Fame: if he’s already in, how the player has been inducted and how quickly; or if he’s not in, whether he received votes, how many, and for how many ballots. We believe this idea lines up closely with how fans regard players, as well. And as far as we can tell, playing in All-Star Games really does matter: Through 2014, of the 128 Hall of Famers who played much or all of their careers in the real-life All-Star era, 53 of them—a full 41 percent—have their All-Star Game participation mentioned right on their plaques.16

In considering the effect that playing many All-Star Games has on a player’s legacy, we believe that the best proxy for determining how good or great his career is involves the Hall of Fame: if he’s already in, how the player has been inducted and how quickly; or if he’s not in, whether he received votes, how many, and for how many ballots. We believe this idea lines up closely with how fans regard players, as well. And as far as we can tell, playing in All-Star Games really does matter: Through 2014, of the 128 Hall of Famers who played much or all of their careers in the real-life All-Star era, 53 of them—a full 41 percent—have their All-Star Game participation mentioned right on their plaques.16

Additionally, Bill James, in his seminal book Whatever Happened to the Hall Of Fame?, cites participation in All-Star Games as a criterion within his “Keltner List” of Hall qualifications, and also awards points to a player for each All-Star Game he participated in as part of the Hall of Fame Monitor evaluation method that he proposed in the book.17

It’s possible that baseball writers or veterans don’t always explicitly consider a player’s participation in All-Star Games as a key criterion to guide their voting, but it also seems implausible to suggest that they give the idea less than short shrift by disregarding it entirely.

With that in mind, let’s explore how participation in All-Star Games during the 1916–32 period might have affected the candidacy of certain players.

INNER CIRCLE HALL OF FAMERS

The first idea to address is whether any current inner circle Hall of Famer would have significantly benefited from playing in any of the All-Star Games that might have taken place between 1916 and 1932, or whether doing so would merely have afforded at least a minor boost by dint of its establishing his place in that particular section of baseball history.

Babe Ruth is probably the best example to contemplate here. In real life, the Babe played in two Midsummer Classics — the first two ever played, actually — and started both. But had the Classic been launched in 1916, the Babe would have made, and started, the games from the very beginning, and, of course, as a pitcher for the first two years. Whether as a starter or as a reserve, Ruth would have made the squad in 16 seasons, tying him with Mickey Mantle, and behind only fellow inner circle Hall of Famers Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Cal Ripken, Rod Carew, Ted Williams, and Carl Yastrzemski, as well as Pete Rose. Ruth would have started games in 15 of those years, as well (he lost the 1922 vote to the Browns’ Ken Williams—more on him later), the same as Carew, and behind only Mays, Ripken, and Aaron. (Note: Appearances and starts for every All-Star in history, including appearances of All-Stars who did not enter the game, as well as pitchers who did not bat, can be found in the All-Star Game Player Career Batting Register at Baseball-Reference.com.)[/fn]“All-Star Game Player Career Batting Register”, accessed August 12, 2014, www.baseball-reference.com/allstar/bat-register.shtml.[/fn]

Making 16 All-Star teams would have been a great accomplishment, of course, and something we would absolutely expect of the greatest baseball player in history. Which is the point: Babe Ruth is already considered the greatest baseball player in history even without all the All-Star Game appearances he surely would have made. The idea that he might have played in 16 of them, rather than just the two in reality, does nothing to further elevate his status, but only because he is already at the pinnacle of the game’s pantheon, and by definition, no one can be elevated above a pinnacle.

This same idea could be applied to a handful of other all-time greats, such as Lou Gehrig, who would have made 13 All-Star teams and started 10 games instead of the actual seven teams and five starts he made; Walter Johnson making six years of All-Star Games and starting three; Grover Cleveland (“Pete”) Alexander with three starts in nine years of making the team; Ty Cobb starting seven games in seven years; or Honus Wagner starting every game of the first two (Retroactive) All-Star series during the last two years of his career.

Making the All-Star rosters, and even being voted All-Star starters, would have been nice incremental honors for these players and may have even provided a handy data point to further argue for their supremacy, but even so, this probably would not have burnished their legacies to any substantive degree, simply because the legacy of each of these players is so nearly perfect to start with.

MIDDLE AND OUTER CIRCLE HALL OF FAMERS

On the other hand, there are some Hall of Famers outside the Inner Circle playing during the RASG period who may have, in a practical sense, benefited from numerous appearances in All-Star Games had they been played between 1916 and 1932.

Harry Heilmann is a good example. Author of a .342/.410/.520 slash line affixed by his 2,660 base hits; winner of four batting titles, including a .403 effort in 1923; and owner of a 148 career OPS+ (which is on-base-plus-slugging indexed to an average of 100, and adjusted for league and park factors); it nevertheless took Heilmann 12 ballots to finally make the Hall of Fame. Alas, Heilmann played his final full season in 1930, three years before the real Midsummer Classic began. Had the All-Star Game begun in 1916, though, our voting would have had him starting nine All-Star Games.

Would this have been enough of a boost by itself to help get him elected to the Hall sooner than he was? Let’s look at a list of the 26 players who started at least nine All-Star Games in real life:

| Player | HoF? | Ballot | GP | GS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willie Mays | Yes | 1st | 24 | 18 |

| Hank Aaron | Yes | 1st | 25 | 17 |

| Cal Ripken | Yes | 1st | 19 | 17 |

| Rod Carew | Yes | 1st | 18 | 15 |

| Stan Musial | Yes | 1st | 24 | 14 |

| Mickey Mantle | Yes | 1st | 20 | 13 |

| Ted Williams | Yes | 1st | 19 | 12 |

| Barry Bonds | Not Yet | — | 14 | 12 |

| Ivan Rodriguez | n/e | n/e | 14 | 12 |

| Yogi Berra | Yes | 2nd | 18 | 11 |

| Brooks Robinson | Yes | 1st | 18 | 11 |

| Ozzie Smith | Yes | 1st | 15 | 11 |

| Wade Boggs | Yes | 1st | 12 | 11 |

| Tony Gwynn | Yes | 1st | 15 | 10 |

| Reggie Jackson | Yes | 1st | 14 | 10 |

| Johnny Bench | Yes | 1st | 14 | 10 |

| Alex Rodriguez | n/e | n/e | 14 | 10 |

| Mike Piazza | Not Yet | — | 12 | 10 |

| Derek Jeter | n/e | n/e | 14 | 9 |

| Ken Griffey Jr. | n/e | n/e | 13 | 9 |

| Joe DiMaggio | Yes | 3rd | 13 | 9 |

| George Brett | Yes | 1st | 13 | 9 |

| Roberto Alomar | Yes | 2nd | 12 | 9 |

| Steve Garvey | No | — | 10 | 9 |

| Ryne Sandberg | Yes | 3rd | 10 | 9 |

| Ichiro Suzuki | n/e | n/e | 10 | 9 |

n/e: not yet eligible as of 2015.

Of the players on this list of 26 elites, 18 are Hall of Famers voted in by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA). Of the eight who are not, five are either active players as of early 2015, or are recently retired and not yet Hall-eligible. Of the three retired players who have achieved eligibility status, one is practically certain to be voted in: Mike Piazza, who has received 57.8 percent, 62.2 percent and 69.9 percent of total votes on his first three ballots, respectively. The candidacy of Barry Bonds, undeniably one of the greatest hitters in history, has been stuck in neutral in his first three ballots due to broad (and controversial) allegations of steroid usage. Steve Garvey is the only player on this list of nine-time (or more) All-Star Game starters who failed to make the Hall after 15 years on the ballot, although in fairness, no one would confuse Garvey’s .294/.329/.446 slash line and 117 OPS+ with Heilmann’s gaudy numbers.

But just as important a point to consider is how quickly the eligible players were voted into the Hall. Fourteen of the 18 Hall of Famers above were first-ballot inductees, two went in on the second ballot, and the other two on the third ballot. That is to say, none of these 18 eligible players had to wait even as long as four ballots. Bonds (who has his own peculiar set of problems) and Garvey (who simply did not have a Hall-worthy career) notwithstanding, Piazza is the first of this list to have to wait at least that long, but only because of the glut of slam-dunk first ballot inner circle Hall of Famers that arrived in 2014 (Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, Frank Thomas) and 2015 (Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez, John Smoltz).

Given his strong showing on his third ballot in 2015, and with the addition of only one surefire first ballot Hall of Famer in Ken Griffey, Jr. the following year, it seems likely that Piazza will go into the Hall in 2016, his fourth ballot. However, that is still a far sight ahead of the 12 ballots it took to elect Heilmann. But then, Heilmann had no All-Star starts or appearances to boast. If Heilmann had had nine All-Star starts listed on his legacy baseball card, though—perhaps he would have gone in much sooner? Probably? Certainly? Our opinion is that the answer might lie closer to the right side of the perhaps-to-certainly continuum than to the left.

Bill Terry was, in reality, a three-time All-Star starter, but had the Game existed before 1933, he is likely to have been an eight-time All-Star, as well as a starter in six seasons. He is well-known as the most recent National Leaguer to have hit over .400 in a season (.401 in 1930), but he is also the current owner of the fifteenth-highest career batting average in history, at .341, higher than such first-ballot elects as Lou Gehrig, Tony Gwynn, and Stan Musial. Terry was a dangerous spray hitter who could hit doubles, triples, and home runs each in great numbers, and he ended his career with a gaudy 136 OPS+ after 14 years.

Terry also had to wait 14 ballots before finally getting his Hall nod. How does that compare to Hall-eligible All-Star Game starters for six seasons in real life?

| Player | HoF? | Ballot | GP | GS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frank Robinson | 1st | 1974 | 14 | 6 |

| Harmon Killebrew | 4th | 1971 | 13 | 6 |

| Mark McGwire | Not Yet | On Ballot | 12 | 6 |

| Billy Herman | Yes | Vet | 10 | 6 |

| George Kell | Yes | Vet | 10 | 6 |

| Kirby Puckett | 1st | 1995 | 10 | 6 |

| Fred Lynn | No | — | 9 | 6 |

| Arky Vaughan | Yes | Vet | 9 | 6 |

| Joe Torre | Yes | Mgr | 8 | 6 |

| Walker Cooper | No | — | 8 | 6 |

| Bill Dickey | 9th | 1946 | 8 | 6 |

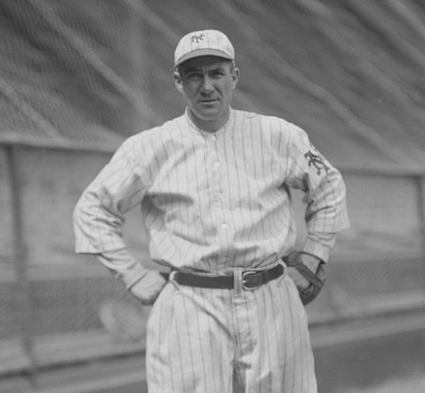

| Charlie Gehringer | 6th | 1938 | 6 | 6 |

Mgr: Elected as Manager; Vet: Veterans Committee selection.

As with Heilmann, Bill Terry’s selection to the Hall seems to have been unusually delayed when compared to others who actually did achieve what might have been Terry’s level of All-Star Game renown. The key exception appears to be Joe Torre, who in his maximum 15 ballots could not obtain any more than 22 percent of the vote. Granted, Torre had a fine 129 OPS+, which is within shouting distance of Terry’s, but he also had a .297 lifetime batting average, which falls short of the minimum benchmark of .300 typically required of those who would be considered great hitters. Dickey‘s (.313 lifetime BA) OPS+ was 127; Gehringer’s (.320) was 124; and Puckett’s (.318) was 124. As hitters, they were clearly not as good as Terry on either a batting average or OPS+ basis, yet they all got inducted far sooner than Terry. As for non-Hall of Famers Fred Lynn (.283/.360/.484, 129 OPS+, off after two ballots) and Walker Cooper (.285/.332/.464, 116 OPS+, three wartime AS selections, off after 10 ballots), the combination of low batting average and the absence of other key HoF markers worked to prevent serious consideration for their induction.

There are a few others to note here: Frankie Frisch (.316/.369/.432, 110 OPS+) was on three All-Star teams and started twice in reality, but would have been on 11 teams and started five times; he went in on the sixth ballot. Gabby Hartnett (.297/.370/.489, 126 OPS+) was on six teams and started thrice, but would have been on 11 teams with seven starts; he did not go in until the twelfth ballot. Jimmie Foxx (.325/.428/.609, 163 OPS+) was on nine All-Star teams already along with four starts, but he would have been on 13 and started seven; he for some reason was made to wait until his seventh ballot for the call. Al Simmons (.334/.380/.535, 133 OPS+) was a starter on all three of his All-Star teams, but would have been on nine teams with eight starts; he was held out from the Hall until the ninth ballot. Dazzy Vance would have been in rare company among pitchers: Already well into his forties with the advent of the All-Star Game, he would have been only one of seven pitchers to start four or more All-Star Games, which, combined with his NL record seven straight league-leading strikeout totals, three ERA titles, and MVP award, may very well have gotten him a writers’ nod to the Hall well before his sixteenth ballot. (Editor’s note: Click here to read “Dazzling Dazzy in the K-Zone” from the Spring 2015 BRJ.)

All this is not to say that lack of, or even paucity of, All-Star Games was the sole reason the elections of these players to the Hall were delayed by several years beyond what would seem reasonable, given their accomplishments. But it is fair to ask: If most similarly accomplished, or even less accomplished, players with long real-life All-Star records were able to skate into the Hall far, far sooner, would the existence of the All-Star Game before 1933—giving a great player like Heilmann the opportunity to be referred to as a nine-time All-Star starter, versus being unable to mention it altogether—have shortened the path to their election by any number of ballots?

Rogers Hornsby is a bit of a special case. Falling sharply off the performance cliff like Wile E. Coyote just before the real-life All-Star Games started, Hornsby would have placed on the RASG roster in 14 seasons, and started every one of them. He is arguably the greatest right-handed hitter in baseball history, owner among starboard-siders of the all-time highest career batting average that anchors a slash line of .358/.434/.577, while clubbing 301 home runs at a time when that was a truly remarkable total. (It was, in fact, the fifth-highest career total at the time of his retirement). Hornsby was a seven-time batting champion, a two-time MVP, and boasts a career OPS+ of 175 that still ranks fifth-highest all-time. Even so, he still did not enter the Hall until his fifth ballot, even ignominiously placing sixteenth on his third ballot behind Johnny Evers and Rabbit Maranville, and barely ahead of Ray Schalk. Would eighteen All-Star starts have helped Hornsby’s case for an earlier election, even as his gaudy stats did not? Considering that Hornsby was universally regarded as a jerk, not least of all by the beat writers of the time, our guess is probably not.

VETERANS COMMITTEE HALL OF FAMERS

Contrary to the opinions of some, the Veterans Committee serves as a good and necessary counterbalance to the neglect of certain qualified players by the voting baseball writers. It’s true that the Veterans Committee sometimes takes a lot of heat, and deservedly so at those times their selections appear to be little more than a sop to certain players of slight talent and accomplishment because they happened to be dandy fellas and/or gritty guys, players such as Ray Schalk, Lloyd Waner, Rick Ferrell, and perhaps a dozen or so others you could name. But sometimes, there is a real injustice that the Veterans Committee addresses with the selection of some players who clearly deserve inclusion on the merits of their records, but for whatever reason were not voted in within their allotted number of ballots by the sportswriters.

Consider the case of Joe Sewell. Seen through the prism of the Hall of Fame, he appears to have possessed borderline talents. He finished his fourteen-year career with a slash line of .312/.391/.413, which translates to an OPS+ of 108, and had a reputation for two things: (1) defense ranging from average to decent; and (2) practically never striking out. He was not elected to the Hall of Fame by the writers, instead falling off the ballot after seven tries. But the Veterans Committee did see fit to elect him in 1977, maybe in part because he was a good guy from the old days, but probably also realizing that even though his numbers may have been only slightly above average for the time, he was still one of the three best shortstops in the game between the world wars. And the RASG voting bears that out: Sewell got eight straight starting nods from RASG voters between 1921 and 1928, and earned a ninth appearance as a reserve in 1929. How might an eight-time All-Star starter have fared with the voting baseball writers of the 1940s and 1950s? Probably better than falling off the ballot after only seven tries.

Another example is Zack Wheat, a fine left fielder and a worthy Hall of Famer, at least as far as the Veterans Committee was concerned. Despite his line of .317/.367/.450, his 129 OPS+ and 2,884 base hits in his exactly 10,000 plate appearances between 1909 and 1927, Wheat was shut out on 16 Hall of Fame ballots, never earning more than 23 percent of the writer vote. On six of those ballots, his vote tally totaled in the single digits. Yet in our RASG, Wheat earned starting nods for seven games in five years between 1916 and 1925, and possibly would have been named to three more had the Games been played before 1916. With that kind of pedigree on his CV, it’s easier to envision Zack Wheat earning a sportswriters’ nod for the Hall.

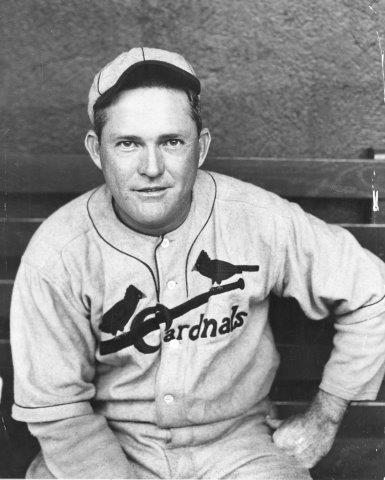

Then there’s Chuck Klein, who at age 23 entered the National League like gangbusters. During his first six seasons and 3,710 plate appearances, he hit .359 overall and led the NL in home runs an astounding four times; runs scored three times; hits, doubles, and RBIs twice, and even led the loop in stolen bases once. Oh, and he won a Triple Crown, as well. The problem is, he accomplished most of this prior to 1933, when there was no actual All-Star Game. He was named to the real All-Star team twice, in ’33 and ’34, with a starting nod that first year, but he certainly would have been voted starter a total of five times, and to the team six times, in his first seven seasons. Given the likely positive bias people naturally have for players who accomplish great things early in their careers, many more All-Star Games would almost certainly have made a substantial impact on Hall of Fame voters. As it turns out, with only two actual Games and a single start on his baseball card, Klein fell off the ballot after 12 tries and was granted a posthumous entry from the Veterans Committee in 1980. If he’d had five All-Star starts in his first seven seasons, though, how might that have affected his chances with the baseball writers voting on his bid for Cooperstown glory?

Other BBWAA vote results for real-life Veterans Committee Hall of Famers include Travis Jackson, a 1982 inductee, a career .291 hitting shortstop with enough muscle to power out 135 home runs, and who started one actual All-Star Game, but made six more Retro All-Star teams including four more starts—he fell off the ballot after 12 tries; Earl Averill, a center fielder who slashed .318/.395/.534 and was rostered on six actual All-Star teams and a starter on three, but who would have been on nine All-Star squads and started five—gone from the ballot after seven years; Jim Bottomley, the 1928 National League MVP who at various times in his career led his loop in hits, doubles, triples, homers, and RBIs, did not make a single real-life All-Star squad, but would have made six RASG squads with a starting bid in three of them—adios after 12 ballots; Ross Youngs, the Giant right fielder who during his ten-year career, which ended after the 1926 season at age 29, slashed .322/.399/.441, had an OPS+ of 130, and would have earned four All-Star starts in the Retroactive era and been named as a reserve on a fifth squad, somehow still made it through 17 ballots before falling off; and perhaps most surprisingly, Frank “Home Run” Baker, who you’d be forgiven for believing easily earned a BBWAA election to the Hall given his three home run crowns, his .307 career batting average, his 135 OPS+, and his evocative sobriquet, but who in fact fell off the ballot after his eleventh bid in 1951 and then easily picked up a Veterans Committee nod four years later.

Perhaps not all of these Veterans Committee selections would have made the grade with the writers during that phase of Hall of Fame qualification, but it does seem likely that with the ability to claim multiple All-Star Game starting bids and overall team selections, they would have done much better in the balloting than they actually did.

NON-HALL OF FAMERS: “DO YOU KNOW ME?”

Not every player who was good enough for a long enough stretch of time to earn multiple All-Star nods during the RASG era would have been, or even should have been, voted into the Hall of Fame (although with the notorious version of the Veterans Committee operating in the 1970s, they still might have made it in—who knows?). But even so, many of the players who made multiple appearances in our Retroactive All-Star Games are not at all well-known, or are downright anonymous even to savvy fans of baseball history.

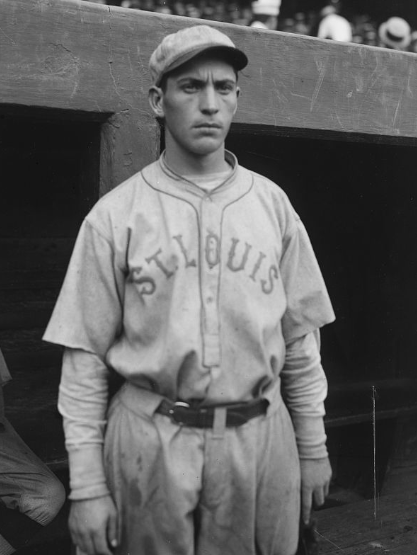

Marty McManus fills this bill. After a teenaged stint working for Uncle Sam during and immediately after World War I, McManus saw a season in the Western League at Tulsa in 1920 before finishing out the year for the Browns in St. Louis, and he never went back down to the minors before completing his long major-league career. McManus averaged over 130 games per year spread out among every spot in the infield over the next 14 seasons with the Browns, Tigers, and Red Sox before moving to the Braves for his last season in 1934, finishing with a slash line of .289/.357/.430 for an OPS+ of 102, very respectable for a middle infielder. He fell just 74 hits short of 2,000, and smacked 120 homers (third all-time among second basemen at retirement) and 401 doubles while stealing 126 bases (leading his league with 23 thefts in 1930), receiving MVP votes four of his seasons. A man characterized by his own wife as having an “ungovernable temper,” he was nevertheless acknowledged in an AP report when traded as being “one of the best second basemen in the game.”18

Marty McManus fills this bill. After a teenaged stint working for Uncle Sam during and immediately after World War I, McManus saw a season in the Western League at Tulsa in 1920 before finishing out the year for the Browns in St. Louis, and he never went back down to the minors before completing his long major-league career. McManus averaged over 130 games per year spread out among every spot in the infield over the next 14 seasons with the Browns, Tigers, and Red Sox before moving to the Braves for his last season in 1934, finishing with a slash line of .289/.357/.430 for an OPS+ of 102, very respectable for a middle infielder. He fell just 74 hits short of 2,000, and smacked 120 homers (third all-time among second basemen at retirement) and 401 doubles while stealing 126 bases (leading his league with 23 thefts in 1930), receiving MVP votes four of his seasons. A man characterized by his own wife as having an “ungovernable temper,” he was nevertheless acknowledged in an AP report when traded as being “one of the best second basemen in the game.”18

The fans participating in RASG recognized as much from his stats, too, voting him a three-time starter, and he made the roster as a reserve for three more teams. During the period 1922 to 1930, only Joe Sewell was a better American League infielder (outside of first basemen) in terms of lifetime Wins Above Replacement (WAR), and McManus’s own WAR was the equal of that of Pie Traynor, an elected Hall of Famer who was roughly the same age, and higher than that of Rabbit Maranville, both in their prime at the same time and both fairly well-known today. Yet, judging by his puny total of four Hall votes in 1958 and 1960, it’s fair to say that McManus himself is largely unknown today. If Marty McManus could claim six actual All-Star appearances, might he be at least as well-known as Traynor and Maranville?

Cy Williams is probably better known than McManus because of his power exploits at the plate. A lifelong National Leaguer who plied his trade first with the Cubs and then with the Phillies, Williams was one of the first players in the live-ball era to start clouting home runs at a prodigious rate, although he also led the league in home runs during the dead-ball year of 1916, one of four times he eventually led his loop in circuit clouts. Like McManus, he, too, stopped just short of 2,000 hits (finishing with 1,981), but he also retired in 1930 with 251 career home runs, which at that time was the third-highest career homers in history behind only Ruth and Hornsby. Williams slashed .292/.365/.470 for an OPS+ of 125 and eventually earned himself placement on 13 Hall of Fame ballots between 1938 and 1960, even though he never achieved even as much as 6 percent of the baseball writers’ votes in any given year. There seems little doubt his home-run power gave him some staying power on Hall of Fame ballots, even if he could not break through to the other side, but despite this circumstance and his on-field achievements, it seems odd he did not get a Veterans Committee nod for his body of work. Perhaps, though, had he been voted an All-Star starter five years while starting seven All-Star games, as he did in RASG, he might have gotten the boost he needed to be considered a better bet for the Hall of Fame, at least by the Old-Timers.

We mentioned earlier the other power-hitting Williams of this era, Ken Williams. He’s not very well-known today and that might be due in part to his name: “Ken Williams” is a fine name, sure, but it’s also a fairly generic-sounding name; it’s a name that’s similar to the guy in the paragraph above who started belting lots of homers at about the same time; and theirs is a last name that in later years became more or less the sole property of one of the greatest pure hitters in the history of the game.

Even more starkly than his not-brother Cy, Ken started belting home runs quite suddenly with the advent of the live ball, going from 10 in 1920 to 24 the next year to an American League-leading 39 the year after that. When Ken hung up his spikes at the age of 39 after the 1929 season, he, too, was quite far up the list of career home run leaders—fourth to be exact, with 196. But he was also a more accomplished hitter overall than Cy. In over two thousand fewer plate appearances, he hit more triples and almost as many doubles as Cy; his lifetime batting average of .319 exceeded Cy’s by nearly 30 points; and his slugging exceeded Cy’s by 60. Ken’s career slash stats after 14 years, mostly with the Browns but also during stints with the Red Sox and Reds, crossed the finish line at .319/.393/.530 accompanied by an OPS+ of 138, roughly equivalent to those of Reggie Jackson, Duke Snider, Chuck Klein, and Bill Terry, Hall of Famers all.

Ken Williams probably could not expect to make the Hall with only 5,600 or so plate appearances (although having fewer than that didn’t seem to hurt Hack Wilson or Frank Chance), but had Ken Williams actually made the six All-Star appearances with four voted starts that he earned in the RASG project, it’s a good bet that we would have a better idea today of who he is and what he did.

Here’s a question that, if you offered it up to the knowledgeable baseball fan of today, you might very well get a blank stare in return: “What can you tell me about Larry Doyle?”

Yet, the baseball fans of a hundred years ago probably could have told you a lot about Larry Doyle. After all, Doyle was voted the MVP of the National League while playing second base for the league-champion Giants in 1912—and this after having finished third in the voting for MVP for the league-champion Giants the year before. In fact, so well-known and highly regarded at the time was Doyle that Baseball Magazine, in one of its articles advocating an All-Star Series, specifically mentioned Doyle, along with Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, Eddie Collins, and Gavvy Cravath, as being among “the greatest aggregation of batters in the world.”19

Yet, the baseball fans of a hundred years ago probably could have told you a lot about Larry Doyle. After all, Doyle was voted the MVP of the National League while playing second base for the league-champion Giants in 1912—and this after having finished third in the voting for MVP for the league-champion Giants the year before. In fact, so well-known and highly regarded at the time was Doyle that Baseball Magazine, in one of its articles advocating an All-Star Series, specifically mentioned Doyle, along with Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, Eddie Collins, and Gavvy Cravath, as being among “the greatest aggregation of batters in the world.”19

Doyle was a career .290/.357/.408-hitting second baseman, and if that sounds just so-so at first blush, consider that his lifetime 126 OPS+ is the eighth-highest among keystone sackers in baseball history—just six points behind Joe Morgan and Jackie Robinson, the same as Robinson Cano (as of mid-2014), and ahead of 13 second basemen currently enshrined at Cooperstown, including BBWAA-elected Charlie Gehringer, Roberto Alomar, Ryne Sandberg, and Frankie Frisch. Doyle led the NL in hits twice; doubles, triples, and batting average once each; and he slugged 74 homers at a time when that really meant something. Sadly, even though he was considered the equal of many inner-circle Hall members at the time, he is barely known today, perhaps in part because he fell off the Hall ballot after three years and only seven votes. But had he been voted an All-Star starter four straight years as he was in RASG—and at the end of his career to boot—how would that have helped his chances for both the Hall and posterity?

As illuminating as these examples are, there are two that stand out as particular favorites of ours:

Larry Gardner was, by election and selection, a three-time RASG All-Star and two-time starter. Certainly not bad, considering his career tracked along that of Larry Doyle’s, so he would have been at the end of his career when RASG started, as well. He is also a largely anonymous player from the period, even though he was second-best third baseman, after Home Run Baker, in all of baseball from 1910 to 1921 in terms of WAR. Much of that high ranking results from his fielding, as he had the best dWAR (a player-comparison metric of defensive value that incorporates offensive productivity weighted by position) during the period, but he was no slouch with the bat, either. He led all third sackers of the period in hits and triples, and was second in doubles. Gardner ended with a .289/.355/.384 slash line, and a 109 OPS+. This is quite a nice line, but seemingly not Hall-worthy…until you consider that George Kell, another third sacker, finished his career with a 112 OPS+, the rough equivalent of Gardner’s. Yet George Kell ended up in the Hall of Fame, while Larry Gardner did not earn even a single vote from the writers! (By the way: Kell was named to 10 All-Star teams and a starter on six of them. Think that might have had something to do with his selection?)

Lastly, let’s consider the case of Jack Fournier. A veteran of 13 full seasons in the majors, with a three-year Pacific Coast League-sized hole in the middle, Fournier swung a mean bat. He clubbed the horsehide at a .313/.392/.483 clip in his career, and once the live ball made its debut, added the home run to his skill set, even leading the NL as a Dodger with 27 in 1924. Fournier, of course, never played in a real All-Star Game, although the sweet-swinging first baseman placed on the RASG roster four times, and was voted a starter three times, during the 1920s. But of course, there was no actual All-Star Game in the 1920s, and possibly as a result Fournier, like Gardner, did not receive a single Hall of Fame vote from the writers.

Fournier ended his career with an OPS+ of 142 and a lifetime oWAR of 44.9. This is the rough equivalent to the output of a star who played a decade later: Hack Wilson, possessor of a lifetime OPS+ of 144 but an oWAR of only 42.5. (oWAR is a player comparison metric that includes a player’s offensive production and a positional adjustment.) Yet Hack is a Hall of Famer who, although selected by the Veterans rather than being voted in by the BBWAA, nevertheless was a mainstay on 15 ballots before his eventual old-timers selection. Some people would point out that Hack Wilson was never an All-Star himself, as his decline coincided with the beginning of the Midsummer Classic, and that he led the league in home runs four times while setting a league season record in that stat, as well as a major-league season record of 191 RBIs, a level of accomplishment that Fournier could not match on any front. And all that would be correct.

But the point here is not to advocate that Jack Fournier should be a Hall of Famer as Hack Wilson is, or that Wilson should not be if Fournier isn’t. The point is that without the kind of credentials that help a player’s Hall chances, such as league leadership in key stats or season records—or All-Star appearances—we get a situation in which a player who had essentially the same career as a well-known Hall of Famer ends up being, for all practical purposes, an anonymous footnote in the annals of baseball history.

Even casual baseball fans know who Hack Wilson is. But only hard-core baseball nerds would have any idea who Jack Fournier is, let alone what he accomplished, and for all that he did accomplish, it seems very unjust that he should not have received even a single vote for the Hall of Fame. Several All-Star appearances, and starts, might have helped Fournier’s legacy.

As sim-gaming baseball geeks, when we first started the RASG project, we were most interested in how the games might come out, perhaps showing us who the better league might have been, or at least which one had the better stars, and how All-Star Game records might have been rewritten. But as we got further into the project, we realized that the true insights arising from this exercise lay in how players who never had the opportunity to play in All-Star Games during the peaks of their careers may have suffered in their legacies and their chances at the Hall of Fame, when compared to players of similar or even lesser accomplishments in later generations.

That is ultimately what made this an eye-opening experience for us, and we hope it was for you, as well.

CHUCK HILDEBRANDT has served as chair of the Baseball and the Media Committee since 2013, and has been a SABR member since 1988. Chuck lives with his lovely wife, Terrie, in Chicago, where he is an exiled Tigers fan who compensates with Cubs season tickets.

MIKE LYNCH was born in the heart of Red Sox Nation in the year of Yastrzemski and has been a diehard Red Sox fan ever since. A member of SABR since 2004, he lives in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. He is the author of three books, “Harry Frazee, Ban Johnson and the Feud That Nearly Destroyed the American League,” which was named a finalist for the 2009 Larry Ritter Award in addition to being nominated for the Seymour Medal; “It Ain’t So: A Might-Have-Been History of the White Sox in 1919 and Beyond”; and “Baseball’s Untold History: Vol I—The People.” His work has also been featured in SABR books about the 1912 Boston Red Sox and 1914 Boston Braves.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jacob Pomrenke of SABR for providing access to the Society’s SurveyMonkey.com account, from which we conducted public voting for the starters of the Retroactive All-Star Games; Sean Forman of Baseball-Reference.com, who provided a blog post and tweets, which increased visibility of the project; and the proprietors of the 30 MLB team websites at SBNation, who allowed us to publicize the project and publish game results as FanPosts on their sites.

Notes

1 “Baseball-Reference.com Play Index,” accessed August 12, 2014, http://www.baseball-reference.com/play-index/. Paid subscription required as of February 2015 to access the Play Index.

2 Lyle Spatz, “Retroactive Cy Young Awards,” Baseball Research Journal 17 (1988): 2–5.

3 Lyle Spatz, “SABR Picks 1900-1948 Rookies of the Year,” Baseball Research Journal 15 (1986), accessed August 12, 2014.

4 A few months after RASG started, B-R added splits data for 1914 and 1915, but the project had advanced too far by that time to practically go back and include those seasons.

5 F.C. Lane, “The All-America Baseball Club,” Baseball Magazine, 1913 December Vol. XII No. 2: 33–44; F.C. Lane, “The Greatest Baseball Team of All History,” Baseball Magazine, 1914 May Vol. XIII No. 1: 33–42, 96.

6 F.C. Lane, “An All-Star Baseball Contest for a Greater Championship,” Baseball Magazine, 1915 November Vol. XVI No. 1: 57–64.

7 F.C. Lane, “Why Baseball Should Have an All-Star Series,” Baseball Magazine, 1916 March Vol. XVI No. 5: 48–52.

8 Lane, “An All-Star Baseball Contest for a Greater Championship,” 64.

9 “Why Baseball Should Have an All-Star Series,” 52.

10 Mike Lynch, “The Complicated History of RBI,” Sports Reference, August 6, 2014, http://www.sports-reference.com/blog/2014/08/the-complicated-history-of-rbi.

11 “Major League Averages,” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 1930.

12 “Major League Averages,” Chicago Tribune, August 16, 1931.

13 Neil Paine, “Feature Watch: Team Batting Orders & Lineups,” Sports Reference, August 24, 2009, http://www.baseball-reference.com/blog/archives/2286.

14 Bill Deane, Baseball Myths: Debating, Debunking, and Disproving Tales from the Diamond (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2012), 121.

15 “Baseball Brawls: Bill Dickey Broke Carl Reynolds’ Jaw With One Punch,” Reading Eagle, August 14, 1960.

16 “National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum: Plaque Gallery”, accessed August 12, 2014, http://baseballhall.org/museum/experience/plaque-gallery.

17 Bill James, Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?: Baseball, Cooperstown, and the Politics of Glory (New York: Simon & Schuster Inc., 1994, 1995), 284, 360.

18 Bill Nowlin, “Marty McManus,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, accessed September 17, 2014, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/3567429b.

19 “Why Baseball Should Have an All-Star Series,” 51.

Appendix A: Retroactive All-Star Game results

| Season | Dates | Field | City | Winner | Recap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1916 | July 14-16 | Comiskey Park | Chicago, IL | NL, 2-1 | Click here |

| 1917 | July 13-15 | Polo Grounds | New York, NY | AL, 2-1 | Click here |

| 1918 | Canceled (war) | ||||

| 1919 | July 19 | Fenway Park | Boston, MA | NL, 4-3 | Click here |

| 1920 | July 17 | Braves Field | Boston, MA | AL, 6-0 | Click here |

| 1921 | July 16 | Dunn Field | Cleveland, OH | AL, 10-8 | Click here |

| 1922 | July 11 | Forbes Field | Pittsburgh, PA | AL, 11-2 | Click here |

| 1923 | July 10 | Yankee Stadium | New York, NY | NL, 10-8 | Click here |

| 1924 | July 8 | Wrigley Field | Chicago, IL | NL, 6-1 | Click here |

| 1925 | July 14 | Shibe Park | Philadelphia, PA | AL, 19-5 | Click here |

| 1926 | July 13 | Sportsman’s Park | St. Louis, MO | NL, 11-5 | Click here |

| 1927 | July 12 | Griffith Stadium | Washington, DC | NL, 4-2 | Click here |

| 1928 | July 10 | Redland Field | Cincinnati, OH | AL, 13-0 | Click here |

| 1929 | July 9 | Sportsman’s Park | St. Louis, MO | AL, 10-7 | Click here |

| 1930 | July 8 | Ebbets Field | Brooklyn, NY | NL, 8-6 | Click here |

| 1931 | July 14 | Navin Field | Detroit, MI | AL, 5-3 | Click here |

| 1932 | July 12 | Shibe Park | Philadelphia, PA | AL, 6-2 | Click here |

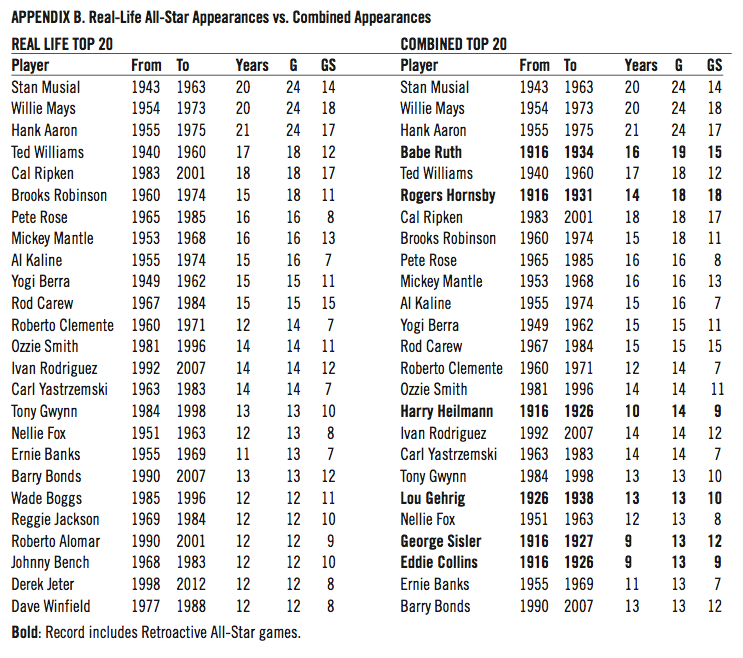

Appendix B: Real-Life All-Star Appearances vs. Combined Appearances

(Click image to enlarge.)

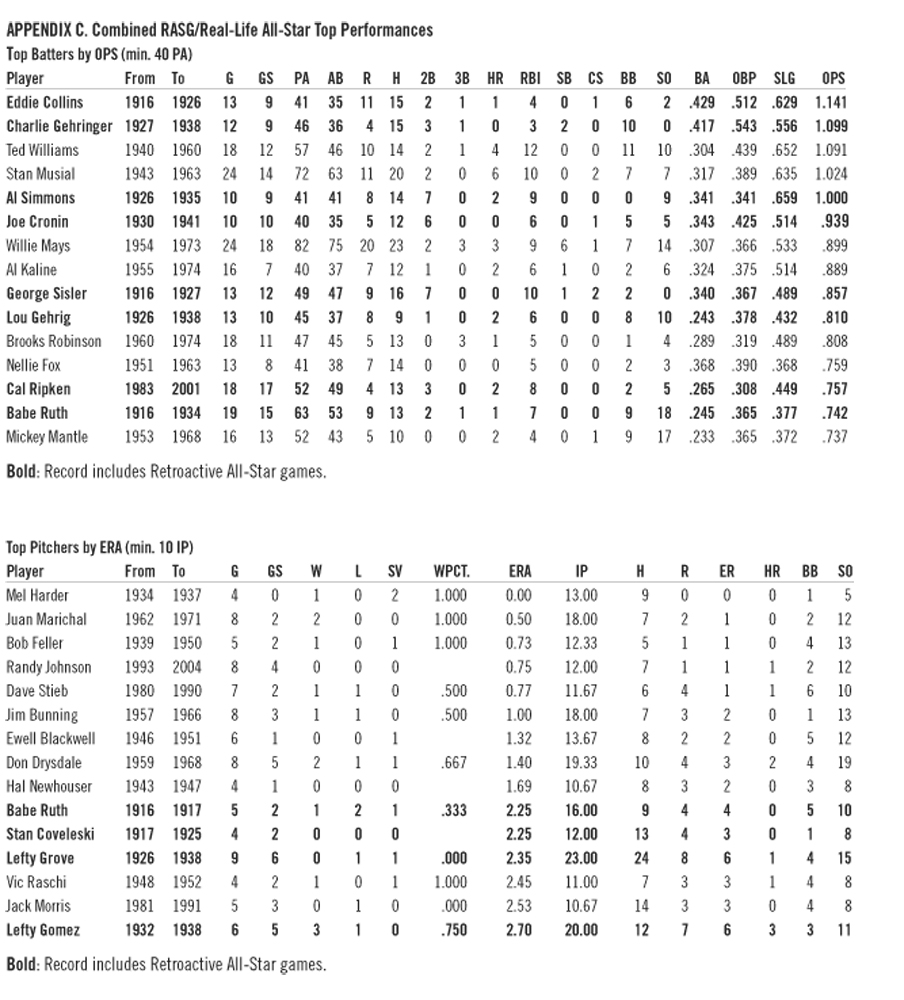

Appendix C: Combined Retroactive All-Star/Real Life All-Star Top Performances

(Click image to enlarge.)