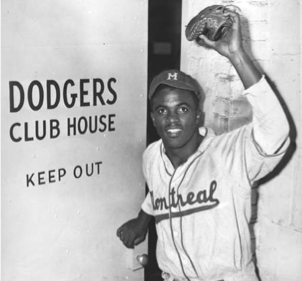

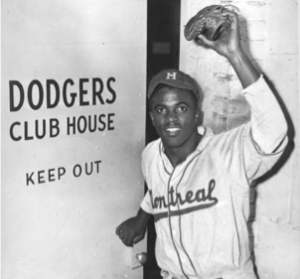

March 17, 1946: Jackie Robinson plays his first exhibition game for Montreal Royals

On October 23, 1945, it was announced that Branch Rickey had signed Jackie Robinson to play for the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ top farm team. The plan was for Robinson to play a season in Montreal to get the professional experience needed to determine if he was ready for the major leagues. In the winter of 1946, newlyweds Jack and Rachel Robinson left their home in Los Angeles for the Dodgers’ spring-training camp. After being bumped off two flights to allow White passengers to have their seats, they had to take a bus from Pensacola to Jacksonville before arriving at the spring-training site. Even on that bus, the Robinsons were ordered to sit in the back.1

On October 23, 1945, it was announced that Branch Rickey had signed Jackie Robinson to play for the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ top farm team. The plan was for Robinson to play a season in Montreal to get the professional experience needed to determine if he was ready for the major leagues. In the winter of 1946, newlyweds Jack and Rachel Robinson left their home in Los Angeles for the Dodgers’ spring-training camp. After being bumped off two flights to allow White passengers to have their seats, they had to take a bus from Pensacola to Jacksonville before arriving at the spring-training site. Even on that bus, the Robinsons were ordered to sit in the back.1

Rickey chose Daytona Beach as the Dodgers’ spring-training site because it had fewer discrimination problems than other Florida cities. During a visit there in September 1945, Rickey noticed something that was different from many Southern cities — Daytona Beach had Black bus drivers, a Black middle class, and a Black political presence.2 Rickey met with Mayor William Perry and City Manager James Titus numerous times before deciding on Daytona Beach. Titus was not at all concerned about Robinson’s presence. He said, “We have a very good situation here between the races because we give the Negroes everything we give the whites. … There is no discrimination, but there is segregation.”3

Daytona Beach, though, did not have enough fields to accommodate the hundreds of players trying out for the many teams in the organization. The Royals trained 40 miles away in Sanford, Florida, until enough players were cut and all of the teams could train in Daytona Beach.

Johnny Wright joined Robinson in spring training so Robinson would have another Black person with whom to work through this journey. Both players were sent to Sanford. The two arrived on the morning of March 4 with Wendell Smith, a writer for the Pittsburgh Courier, at the time the largest Black newspaper in the country, along with Billy Rowe, a Courier photographer. Smith had been hired by Rickey to look after Robinson and Wright.4 As the four men stood in their street clothes and looked across the field at Sanford, they saw a couple of hundred Montreal and St. Paul players taking batting practice and shagging flies, among other spring-training activities. As soon as the players saw the four Black men, Robinson recalled, “It seemed that every one of these men stopped suddenly in his tracks and that 400 eyes were trained on Wright and me.”5

After just the second day of practice, a White man told Black journalists that 100 or so townspeople would take matters into their own hands if Robinson and Wright were not “out of town by nightfall.”6

The two immediately returned to Daytona Beach and trained at Kelly Field in the Black section of town. Smith and Rickey wanted to keep this incident as a secret, to avoid fueling any fires that might be stoked by reporters who did not want the two to play major-league baseball.7

Daytona Beach was a better place for Robinson and Wright to stay and play baseball. The city was home to Bethune-Cookman College, founded by Mary McLeod Bethune, one of the nation’s most influential Black citizens. Bethune gained the respect of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt. The first lady even appeared at a couple of fundraisers for the college. Events like this brought local Black and White residents together in a positive way.8

In Daytona Beach the Robinsons stayed with Joe and Duff Harris. Joe was a pharmacist and business leader in town. Wright stayed with Vernon Smith, a retired real estate agent. Smith and a couple of others involved in helping Robinson and Wright stayed at the college. The White players stayed in the Riviera Hotel.9

On the field, Robinson tried to impress his coaches by throwing the ball as hard as he could but hurt his arm in the process. His hitting also suffered. He said, “I could hear them shouting in the stands, and I wanted to produce so much that I was tense and over-anxious. I found myself swinging hard enough to break my back. I started swinging at bad balls and doing a lot of things I wouldn’t have done under ordinary circumstances. I wanted to get a hit for them because they were pulling so hard for me.”10

After the first day of practice, Robinson’s arm was so sore he could barely lift it and had trouble sleeping that night. Royals manager Clay Hopper told Robinson to rest for a few days. At night Rachel would massage his arm, but that didn’t help. Time was needed to work it out.

When Rickey heard that Robinson was taking off some time from fielding, he left City Island Ballpark, where the Dodgers played, and paid a visit to Kelly Field. He told Robinson he had to practice every day, sore arm and all. Rickey said, “Under ordinary circumstances, it would be all right, but you’re not here under ordinary circumstances. You can’t afford to miss a single day. They’ll say you are dogging it, that you are pretending your arm is sore.”11

Because Robinson couldn’t throw across the field and the Royals already had six shortstops in camp, Robinson had agreed to play second base or wherever they need him. Because playing first base did not require having a strong throwing arm, the ballclub switched his position. Having never played first, Robinson struggled. Rickey and Hall of Famer George Sisler tutored him at first base.12

Montreal began its spring schedule against its organizational rival St. Paul Saints. Robinson sat out the first four games to rest his arm. Rickey waited for the right time to reveal Robinson to the baseball world.13

Robinson was penciled into the lineup on Sunday, March 17, as the Royals played the parent Dodgers at City Island Ballpark in downtown Daytona Beach.

Besides learning a new position, having an arm so sore that he couldn’t throw, and being unable to find his hitting stroke, Robinson kept worrying about other things that morning. He kept worrying about what could go wrong — what the White spectators would yell at him, throw at him, or even the possibility that his life might be in danger. But there was excitement in the Black community that morning. In church, they prayed for Robinson and heard sermons about him. After church, the Black community paraded to the ballpark.14

More than 4,000 spectators filled the stands for the game, and about one-fourth were black. They filled the Jim Crow section of the ballpark, and an additional 200 or so Blacks stood beyond the right-field foul line.

Montreal did not score in the top of the first, and in the bottom of the inning, the big hit was Dixie Walker’s bases-loaded triple for the Dodgers, who held a 4-0 lead after one inning.

Robinson came up to bat in the second inning. He wondered what was going to happen. He expected to hear applause from the Black section out in right field but was surprised to also hear applause from the Whites. He remembered two comments coming from the stands. One was “Come on, Black boy! You can make the grade” and “They’re giving you a chance — now come on and do something about it.”15

In his first at-bat, Robinson chased a curveball and fouled out weakly to third baseman Billy Herman. In the fourth inning, he fouled out to the catcher, Dixie Howell. Robinson put the ball in play in the sixth inning and reached on a fielder’s choice. He stole second and scored on a base hit. He was removed from the game after 5½ innings to rest his arm. Brooklyn went on to win, 7-2.16 Not a whole lot was mentioned in the newspapers about Robinson. None of the high-powered New York sportswriters mentioned the game, and while Daytona Beach Evening News sports editor Bernard Kahn covered the action, he did not write about Robinson until the fourth paragraph. The Associated Press started its story with Robinson, and its dispatch appeared in papers nationwide.17

Even though Robinson did not get a hit, he was satisfied with how the day ended, and a huge burden was lifted off his back. Even though not everyone applauded for him, he was sure now that the whole world wasn’t against him. The townspeople were equally satisfied.18

When camp broke and the Royals returned to Montreal for the International League season, Robinson had made the team. He and Rachel were uncertain what kind of reception they would face. It turned out well. They found a place to live, and in the Royals’ season opener, Robinson went 4-for-4 with a home run. He went on to lead the International League in batting average (.349) and tied for runs scored with Soup Campbell of the Baltimore Orioles (113). The Royals won the pennant with a 100-54 record and defeated the Louisville Colonels, the American Association champion, in the Little World Series.19

In 1988 City Island Ballpark was renamed Jackie Robinson Ballpark, and is still in use as of 2020.20

Notes

1 Chris Lamb, Blackout: The Untold Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Spring Training (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 13-16.

2 Lamb, 64.

3 Lamb, 64.

4 Hall of Fame, “About Wendell Smith,” baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/wendell-smith/345.

5 Lamb, 83.

6 Lamb, 88.

7 Lamb, 88-89.

8 Lamb, 91.

9 Lamb, 92-93.

10 Lamb, 94.

11 Lamb, 95.

12 Lamb, 95.

13 Lamb, 100.

14 Lamb, 104.

15 Lamb, 106.

16 Associated Press, “Robinson Is Hitless in 3 Tries as Dodgers Wallop Royals 7—2,” Montreal Gazette, March 18, 1946: 17.

17 Lamb, 107.

18 Lamb, 108.

19 Tabitha Marshall, The Canadian Encyclopedia, thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jackie-robinson-and-the-montreal-royals.

20 Kevin Reichard, Ballpark Digest, ballparkdigest.com/200811291030/minor-league-baseball/visits/jackie-robinson-ballpark-daytona-cubs.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Dodgers 7

Montreal Royals 2

City Island Ballpark

Daytona Beach, FL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.