Where Was Satchel in 1935? Paige and Greenlee Feuded as Crawfords Ruled the NNL

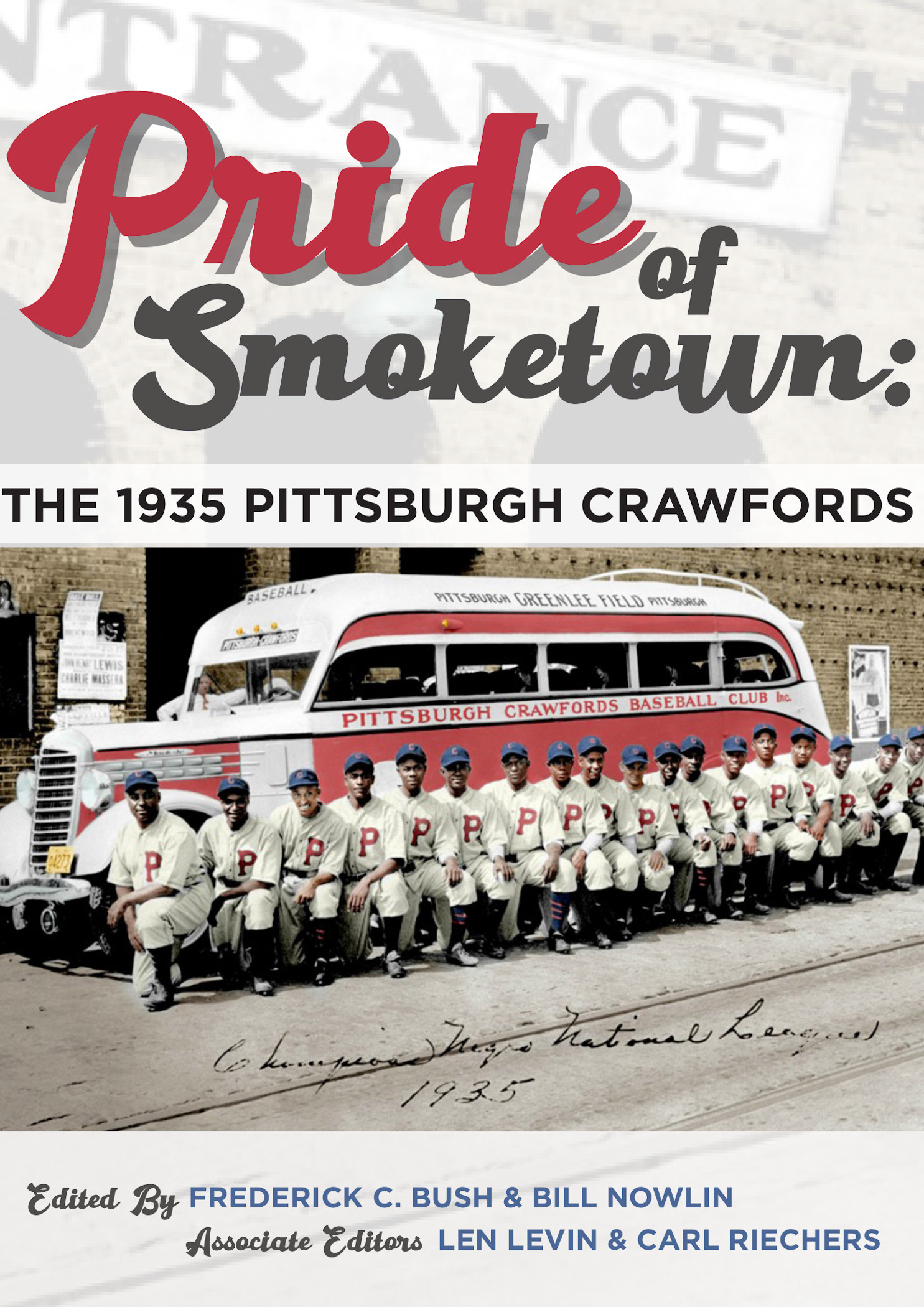

This article appears in SABR’s “Pride of Smoketown: The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords” (2020), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

As the 1935 baseball season approached, Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee had every reason to be optimistic about his team’s chances to win the Negro National League championship. Although the 1934 squad had finished in second place in both halves of the season, it still posted a 47-27-3 record in league play, and the returning roster was the most imposing in all of Negro baseball.1 The Crawfords had four future Hall of Famers in James “Cool Papa” Bell, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, and Judy Johnson along with stalwarts like Sam Bankhead, Jimmie Crutchfield, Roosevelt Davis, Leroy Matlock, and Andrew “Pat” Patterson. Greenlee also anticipated the return of a fifth future Hall of Famer in the person of Satchel Paige, who had led the 1934 Crawfords’ pitching staff with a 13-3 record, 152 strikeouts in 145⅔ innings pitched, and a minuscule 1.54 ERA. In fact, Greenlee had gone to great lengths to ensure that Paige would come back, but he found out – as did so many other owners over the course of Satchel’s career – that nothing was certain where the lanky hurler was concerned. As it turned out, bad blood between Greenlee and Paige led to each man having to fend for himself and resulted in the most unusual circumstance of both emerging as champions.

As the 1935 baseball season approached, Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee had every reason to be optimistic about his team’s chances to win the Negro National League championship. Although the 1934 squad had finished in second place in both halves of the season, it still posted a 47-27-3 record in league play, and the returning roster was the most imposing in all of Negro baseball.1 The Crawfords had four future Hall of Famers in James “Cool Papa” Bell, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, and Judy Johnson along with stalwarts like Sam Bankhead, Jimmie Crutchfield, Roosevelt Davis, Leroy Matlock, and Andrew “Pat” Patterson. Greenlee also anticipated the return of a fifth future Hall of Famer in the person of Satchel Paige, who had led the 1934 Crawfords’ pitching staff with a 13-3 record, 152 strikeouts in 145⅔ innings pitched, and a minuscule 1.54 ERA. In fact, Greenlee had gone to great lengths to ensure that Paige would come back, but he found out – as did so many other owners over the course of Satchel’s career – that nothing was certain where the lanky hurler was concerned. As it turned out, bad blood between Greenlee and Paige led to each man having to fend for himself and resulted in the most unusual circumstance of both emerging as champions.

The animosity between Paige and Greenlee that kept the pitcher from donning a Crawfords uniform in 1935 had its origins, oddly enough, in Paige’s marriage to Janet Howard, who was a waitress at Greenlee’s Crawford Grill. The couple tied the knot on October 26, 1934, with tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson as Satchel’s best man, and Greenlee threw a lavish wedding reception at the Grill afterward. Greenlee had an ulterior motive behind his generous gesture: he used the occasion to announce that Paige would be signing a new two-year contract to return to the Crawfords. In his autobiography, Paige stated that he had agreed beforehand to this move and recalled, “While they still were yelling and cheering, Gus and I sat down and signed the contract.”2 Paige and his bride went on their honeymoon to California, where Satchel played for Tom Wilson’s Nashville Elite Giants during the California Winter League season.

The Elite Giants team, which in addition to Paige also included fellow Hall of Famers Cool Papa Bell, Turkey Stearnes, Mule Suttles, and Willie Wells, dominated the California Winter League with a 34-5-1 record and won the pennant for the 1934-35 season. Though Paige arrived in the Golden State after the campaign had started, he was still the center of attention whenever and wherever he pitched, and he compiled a perfect 8-0 record in league play with 104 strikeouts in 69 innings pitched.3

Although Greenlee had paid most of Paige’s wedding expenses and also had funded the honeymoon, and Paige was earning money for his winter league play, all was not well financially for Satchel. The spendthrift Paige observed, “After that honeymoon, I started noticing a powerful lightness in my hip pocket. Married life was a mighty expensive thing and those paychecks of mine weren’t going as far as they used to.”4 His solution was to hit Greenlee up for a raise, even though he had not yet done anything to earn the money he had coming to him on his new Crawfords contract.

Paige’s meeting with Greenlee did not go as he had expected it would. In his account of their summit, Paige wrote, “[G]us was mad or something like that. He turned me down flat. … All he said was something like ‘don’t forget those games we got coming up next week.’”5 Satchel could not have cared less about “those games,” and he remembered, “I was so mad I went home and started throwing clothes into a suitcase”6 and told Janet that they were leaving Pittsburgh. According to Paige, a few days later he called Neil Churchill, a car dealer and semipro baseball team owner-manager, and received an offer to return to Churchill’s integrated squad in Bismarck, North Dakota. Paige had pitched for Churchill in 1933, had spurned him in 1934 – as he was now doing to Greenlee – and took his new wife with him to Bismarck for the 1935 season.

Greenlee was irate at Paige’s departure. He called Churchill and warned him “that he’d carve him to pieces if he ever got within knife-slashing distance, a threat that had to make Churchill glad for every inch of the 1,124 miles between Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Bismarck, North Dakota.”7 Instead of traveling west to commit murder, Greenlee first tried to unload Paige’s contract since he still considered the pitcher to be his property. A February 9 article in the Chicago Defender reported that Paige “is the most sought after ball player in the land today, or he was, until Gus announced the salary his star was receiving” and his fellow team owners pointed out that they “cannot afford to pay such salaries and continue to operate.”8

Paige arrived in Bismarck on March 24 to prepare for spring training with Churchill’s team. Soon thereafter, in mid-April, Greenlee revealed what he had decided to do about his impasse with Paige over the pitcher’s services. The Chicago Defender summarized the state of affairs in one succinct paragraph:

“W.A. Greenlee announces that Satchell [sic] Paige has been assigned to Ray L. Dean, western promoter for one year. It is believed that the sensational righthander is being disciplined and will be required to perform for the House of David. A clause prohibiting his appearance or service in games against league clubs has been inserted.”9

Paige had helped the House of David squad win the Denver Post Tournament in 1934, but he had no intention of returning to the team, and he was unconcerned about being banned from playing for, or against, NNL teams.

There was as much sparring in the press over Paige’s contract-jumping as there was between Satchel and Greenlee. Pittsburgh Courier columnist Chester Washington heartily approved of Greenlee’s banishment of his ace pitcher, writing, “Heroes come and heroes go. The champ of today may be the ‘chump’ of tomorrow. So it may be with Paige. The league helped to make him and now the League may be the medium to break him.”10

Chicago Defender columnist Al Monroe, on the other hand, was in the pro-Satchel camp and wrote of Paige’s motivation: “(Paige knows that) big pay can be asked only while you are at the top after which the club owners set the figures, which you either take or leave.” Monroe made an apt comparison as he wrote, “Babe Ruth, you will remember, employed the greatest part of each spring training period arguing over what he was to receive for playing during the regular season and usually got what he asked for,” and he asserted, “Say what you will or may, there is little doubt but that Satchel Paige is the Babe Ruth of Race baseball.”11

While most of the press focused on Paige, Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey made the astute observation that, although he still expected Satchel to return to Pittsburgh for the 1935 season, “without Paige the [Crawfords] club is evenly balanced and contain [sic] some of the best players in colored baseball.”12

On April 24, the Bismarck Tribune announced that Churchill’s squad would open the season against Jamestown on May 5.13 Greenlee’s threats, reassignment of Paige to the House of David, and NNL ban notwithstanding, it was a foregone conclusion that Paige would start for Bismarck on Opening Day. As Satchel later recalled, “I didn’t do anything about the noises Gus was making. … Those Negro league owners were just spiting themselves, I figured. … There was plenty of green floating in and I was getting my share of it, but Gus and his pals weren’t.”14

Surprisingly, Satchel lost Bismarck’s opener, 2-1, in spite of holding Jamestown to five hits and striking out 10 batters.15 It would be one of his few setbacks in all of 1935. Paige also still was able to test his mettle against some of the best players the Negro Leagues had to offer, because Greenlee’s NNL ban did not preclude him from playing against NAL teams. On June 6 Bismarck faced the Kansas City Monarchs in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and Paige dueled with Chet Brewer in an instant classic. The press raved that “Paige struck out 17 batters. Brewer, of Kansas, also a colored boy, struck out 13, making the amazing total of 30 strikeouts in one game. The score, incidentally, was 0-0.”16

Meanwhile, Paige was still being used as a drawing card for Crawfords games. On June 13 the Delaware County Daily Times, in a preview article for the Pittsburgh nine’s game against a semipro team from Chester, Pennsylvania, wrote, “Paige may not pitch the entire game tonight, but the Crawford management has assured Vann that he will work part of the contest.”17 Two days later, the same newspaper had to explain, “The reason Satchel Paige didn’t show with the Crawfords against Vann’s team is because the lanky pitcher is in North Dakota. He is still the Crawfords’ property in the Negro League.”18 The tactic of tempting fans to attend Crawfords games in hopes of catching a glimpse of Paige ended up backfiring tremendously on Greenlee in late September.

By early July, Paige sported a 16-2 record for Bismarck,19 while the Crawfords were headed toward the first-half NNL title. Soon, voting was underway for the Negro Leagues’ third annual East-West All-Star Game, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on August 11. The Pittsburgh Courier reported that Crawfords pitcher Leroy Matlock “is having his greatest year, and has caused Smoketown [Pittsburgh] fans to forget Satchell [sic] and his ‘fast ball,’” but it added, “That Satchell has not been forgotten altogether, however, is manifested by the votes which show he still has prestige.”20 Paige may have hoped that he would be allowed to participate in the East-West game; however, as the Chicago Defender noted, “[t]he moguls refused to gamble on the big fellow. And as a result Paige must now sit back and watch [other pitchers] grab off the glory that was once his.”21

As the season progressed, Churchill continued to add Negro Leaguers to his Bismarck squad, and the formidable team now included Hilton Smith, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Barney Morris, Quincy Troupe (who had not yet added the second ‘p’ to his last name), and Red Haley. Bismarck participated in three tournaments in Manitoba, and invariably faced the Devil’s Lake, North Dakota, team for each title. They lost the Brandon Tournament in July, but won both the Portage La Prairie and Virden Tournaments in early August.22

It seemed that the only thing that might have stopped Bismarck’s domination of its opponents that season would have been for something to sideline Paige, which almost happened. Quincy Trouppe recounted the anecdote in his autobiography:

“Coming back from a little trip to Winnipeg, Canada, in my car, Satchel began to ride me. … As I was driving along, engrossed in his joking, I missed a curve sign. … We skidded into a ditch on the side of the road and bounced back onto the road into the other bend of the ‘S’ curve. When we made it through that, I stopped the car.

“Barney Morris opened the door on his side in the back and fell out, rolling into the ditch, yelling, ‘Oh! Oh! Lord!’

“I bolted out of the driver’s seat, ran around back, and slid into the ditch beside Barney. … I knelt beside him, anxious … he was convulsed with laughter. … ‘Hey, what’s wrong with you?’ I asked.

“He pointed toward the front door of the car where Satchel was just emerging, and roared anew. ‘Oh, Lord! I’ve never seen anything like that – that big man getting down on the floor rolling into a ball. Man, what a sight!’ He was enjoying every minute of it. …

“Satchel came to the ditch, too, and told Barney, ‘Look, I don’t know what you’re laughing about, but whatever it is, it ain’t funny!’ Then Satch gave me the full measure of his steady gaze. ‘Look heah, Troupe, if you can’t drive this jalopy no better than this, you better let me take over.’”23

With Haley driving the rest of the way, the foursome made it back to Bismarck in good order, and the team continued to roll over all opponents. After the squad’s regular-season finale on August 11, the Bismarck Tribune rhapsodized:

“With an overture of five home runs in the first inning opening a riotous grand opera of extra-base hits and a profusion of singles, Bismarck’s mightiest baseball team sang its swan song for the season to home fans Sunday afternoon by crushing the Twin City Colored Giants, 21 to 6.

“The booster game victory was Bismarck’s 12th in a row and its 66th for the season thus far against 14 losses and four ties.”24

In light of the romp, Paige was up to some old shenanigans, as the Tribune also noted, “The game ended with only Bismarck’s battery on the field, lanky Satchel Paige in the box and Barney Morris behind the plate. This unusual calling in of the fielders gave the visitors one more home run and two more runs than they rightfully earned.”25

Churchill had been seeking stiffer competition for his squad that also would provide greener financial pastures. The annual Denver Post Tournament, which took place in early August, would have been the logical choice over the minor Canadian tourneys, but racism and segregation had reared their ugly heads once again and prevented the Bismarck team’s participation in Colorado. Paige and catcher Bill Perkins had helped to lead the House of David to the 1934 championship in Denver. As a result, in 1935 the tournament’s organizers “banned a colored pitcher from performing on either a white or a mixed ball club,” although one all-black team would be allowed to participate.26 New York Age columnist Lewis E. Dial reported, “In the meet last year an American Legion team had a Negro on its roster and one southern club refused to play that team” and then stated in no uncertain terms, “The powers that be ruled against the crackers, but this year they have tried to safeguard the dough for the white boys by issuing such an asinine ruling.”27

As good fortune had it, however, Raymond Harry “Hap” Dumont had formed the National Baseball Congress of semipro teams in 1934 and wanted to start a tournament in his hometown of Wichita, Kansas, that would bring together teams from around the country and which would rival the Denver Post’s contest. Dumont needed a drawing card and Churchill had just the right one in Paige. Fortunately, there was sufficient cash for the endeavor since “[i]t cost Hap Dumont $1,000 to get Churchill to bring his team and his crowd-pleasing pitcher to Wichita.”28

Everyone – Dumont, Churchill, and the fans – got their money’s worth as Bismarck continued its season-long domination in the NBC Tournament. Before the championship game, the Bismarck Tribune recapped how the local nine had fared to that point: “Bismarck turned back the Monroe, La., Monarchs, 6-4; beat the favored Wichita Watermen, 8-4; defeated the Denver Fuelers [the winners of that year’s Denver Post Tournament], 4-1; trounced Shelby, 7-1; conquered Duncan, 3-1 and walloped Omaha, 15-6.”29 The title game was a rematch against the Duncan (Oklahoma) team that Bismarck – with Paige making his fourth start – won, 5-2, to capture the inaugural NBC championship.

The Bismarck Tribune extolled Paige’s performance after he had thoroughly dominated the field, and reported, “The ebony hurler struck out 66 batters, allowed only 29 hits, and issued five bases on balls during the five games he was on the slab for Bismarck” [Paige had relieved Chet Brewer in the game against Wichita].30 The team played several post-tournament exhibition games that included another tilt against the Kansas City Monarchs in which Paige this time “whiffed 16 batters despite a cold, damp day” in an 8-4 Bismarck triumph on September 4.31 One week later, it was reported that “Satchel Paige, dubbed by sports writers as the ‘Dizzy’ Dean of the Negro pitching world … joined the Kansas City Monarchs for a winter tour of the south.”32

Greenlee no doubt had taken notice of all the publicity Paige had generated for Bismarck, the NBC Tournament, and now the K.C. Monarchs, and he set aside his grudge toward Paige for the sake of his own profit. He offered Satchel $350 to pitch for the Crawfords in a four-team doubleheader at Yankee Stadium on September 22, which turned out to be exactly one day after the Crawfords won the NNL championship series over the New York Cubans, four games to three.

Greenlee put the word out and, on September 18, the news was trumpeted that “‘Satchel’ Paige, the greatest pitcher in colored baseball, will oppose his old rival, Slim Jones, on the mound in the Pittsburgh Crawfords-Philadelphia Stars battle … next Sunday afternoon.”33 Three days later, the Chicago Defender reported, “All eyes this Sunday will be focused on Comiskey Park where it is expected fifteen thousand fans will gather to see the great Satchel Paige with the Kansas City Monarchs versus the American Giants in a game which will go a long way towards deciding the Western championship[,]” and also noted that Paige had been “signed by the Monarchs for this important series.”34 As great as Paige was, even he could not be in two different places at the same time.

On September 22 Satchel was in Chicago, where he pitched five innings of shutout ball for the Monarchs before ceding the mound to Chet Brewer in a 7-1 loss to the American Giants. Farther east, in New York, “A crowd of more than 15,000 fans were disappointed at Yankee Stadium … when Satchel Paige, star pitcher, failed to appear as advertised and when ‘Slim’ Jones, who last year beat Paige in a pitching duel, was knocked out after only one inning on the mound.”35 As they had done all season long in 1935, the Crawfords fared just fine without Paige and beat the Stars, 12-2, but the fans and the New York press were not pleased.

The New York Amsterdam News, in particular, felt embarrassed that it had unintentionally misled fans by reporting that Paige would pitch at Yankee Stadium on September 22. Artie La Mar wrote, “The sporting editor of the Amsterdam News has been in a position to know that the promoters had good reason to believe that Paige would show up but the fans did not know that.”36 La Mar addressed accusations that harkened back to false claims that Paige would pitch for the Crawfords, such as the one made on June 13 in Chester, Pennsylvania: “In speaking of the affair Dan Parker said in the Mirror: ‘Promoters of the colored baseball games at the Yankee Stadium last week advertised Satchel Paige as one of the players, though they knew he was playing in Chicago that day. This cheap gag is used on other large cities, too. It surprises me that Satchel doesn’t sue for damages.’”37 According to La Mar, however, there was a witness, R.L. Dougherty, who “said he has seen money wired to Paige by Greenlee, therefore it should be easy for Greenlee to give his side of the case” and asserted that, due to this eyewitness testimony, “From what could be gleaned on this end of the unfortunate affair it would seem that Satchel is the one who is surprised that he isn’t being sued.”38

The problem was that Greenlee had told a somewhat different story. After Paige’s no-show, he told the press that “the western star stopped off in Chicago enroute east and while there was offered $500 to pitch for the Kansas City Monarchs on Sunday. This causing him to forget all about his agreement to appear in New York …”39 Since the exact date of the alleged Greenlee-Paige agreement was never reported, it remains a mystery as to who was telling the truth. Given Paige’s propensity to follow the money, it is possible that Greenlee had contacted him about the Yankee Stadium game before Satchel’s signing with the Monarchs; in this scenario, Paige reneged on the deal by failing to show up in New York. On the other hand, Dan Parker may have been correct, and Greenlee may have lied about Paige pitching for the Crawfords; if that was the case, it is likely that Greenlee assumed that his offer would be sufficient enticement for Satchel to rejoin the team for one game. When Paige failed to show up, Greenlee had to do damage control and invent a story to cover for his blunder. The bottom line, as the Amsterdam News stated, was that “[n]o matter who is right in the premises there are a number of fans all het up over the non-appearance of Satchel Paige in the line-up of the Pittsburgh Crawfords. …”40

One person who was not “all het up” was Satchel Paige, who tended simply to ignore controversy and negative press because he knew that his pitching prowess would always lure back both owners and fans. He simply continued to pitch for the Monarchs in the early fall. On October 6 in Kansas City, Paige “hurled a three-hit ball game … but it wasn’t enough to beat the touring exhibition team headed by Dizzy and Paul Dean and Mike Ryba. The exhibition team won, 1-0.”41

Shortly thereafter, Paige finished 1935 in the same circuit where he had started it, the California Winter League. A November 23 headline in the Chicago Defender read, “Satchel Paige Stars in California Winter Loop,” and the article reported on Paige’s latest feats.42 On November 16, Paige had hurled five innings for Tom Wilson’s Elite Giants in which he had allowed Pirrone’s All Stars only two hits and struck out seven before giving way to Bob “School Boy” Griffith, who finished a 7-0 shutout victory.

In the yearlong battle of wills between Greenlee and Paige, both were fortunate to emerge with team championships. However, Paige ended up as the ultimate victor because he had the talent and the drawing power that Greenlee needed. After Paige once again ruled the California Winter League to the tune of a 13-0 record43 and pitched successfully against exhibition teams of major-league all-stars, there was talk about Paige being signed to a major-league team. Paige himself realized that, at that point in time in America, it was empty talk, but he figured that it nonetheless was the reason why Greenlee conceded defeat prior to the 1936 NNL season.

In his autobiography, Paige recounted how quickly the two made up:

“‘We’ve lifted the ban on you,’ he told me. ‘When can you rejoin the team?’

“‘I’ll have to do some thinkin’ on that,’ I told him.

“I didn’t have to do as much thinking as I thought. Janet jumped me real quick about it when I told her.”44

Somewhat grudgingly, Satchel acceded to his wife’s wishes: “I got ahold of Gus and told him I was coming back.”45

In 1936 Gus Greenlee and Satchel Paige became champions together as Paige pitched to an 8-2 record for the Crawfords, who captured their second consecutive NNL title.

FREDERICK C. BUSH joined SABR in March 2014. Since that time he has written articles for numerous SABR books as well as the BioProject and Games Project websites. In addition to co-editing the current volume, he has served in the same capacity for the books Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series and The Newark Eagles Take Flight: The Story of the 1946 Negro League Champions. Rick lives with his wife, Michelle, their three sons, Michael, Andrew, and Daniel, and their Border collie mix, Bailey, in the greater Houston area. He is in his 16th year teaching English at Wharton County Junior College’s satellite campus in Sugar Land.

Sources

Unless otherwise indicated, Seamheads.com has been used as the source for all Negro League statistics, team records, and championship series.

Notes

1 The first-half champion Philadelphia Stars won the 1934 NNL title by defeating the second-half champion Chicago American Giants in the NNL championship series by four games to three, with an additional game ending in a tie.

2 Leroy (Satchel) Paige, as told to David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 86. (Originally published by Doubleday & Company in 1962).

3 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 171.

4 Paige, 86.

5 Paige, 87.

6 Paige, 87.

7 Tom Dunkel, Color Blind: The Forgotten Team That Broke Baseball’s Color Line (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013), 129.

8 “Everybody Wants Satchel Paige, Nobody His Salary,” Chicago Defender, February 9, 1935: 16.

9 “Paige’s Contract to the House of Davids,” Chicago Defender, April 27, 1935: 17.

10 Chester Washington, “Sez Ches: Contracts or ‘Scraps of Paper’?” Pittsburgh Courier, April 20, 1935: 16.

11 Al Monroe, “Speaking of Sports,” Chicago Defender, April 13, 1935: 16.

12 “Cum Posey’s Pointed Paragraphs,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 4, 1935: 14.

13 “Capital City Team to Make ’35 Debut Against Jamestown,” Bismarck Tribune, April 24, 1935: 8.

14 Paige, 96.

15 “Capital City Team Makes Home Debut Against Jamestown Sunday,” Bismarck Tribune, May 11, 1935: 6.

16 “Paige Whiffs 17 Monarchs,” Regina (Saskatchewan) Leader-Post June 8, 1935: 17.

17 “Famous Negro Team Here with All Star Line-up,” Delaware County Daily Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), June 13, 1935: 19.

18 “Sports Shorts,” Delaware County Daily Times, June 15, 1935: 10.

19 “Red Sox to Start Starr or Brady in Inter-City Contest,” Bismarck Tribune, July 6, 1935: 6.

20 “Race for E-W Berths Hot as Voting Spurts/Outfield and Infield Races Grow Hectic,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 27, 1935: 15.

21 “Satchel Paige’s Aim Out,” Chicago Defender, August 3, 1935: 14.

22 “Devil’s Lake Noses Out Bismarck, 2-1, to Win Brandon Tournament,” Bismarck Tribune, July 18, 1935: 8; “Bismarck Blanks Devil’s Lake in Canadian Tourney Finals,” Bismarck Tribune, August 6, 1935: 6; “Capital City Team Wins 2nd Manitoba Tournament Crown,” Bismarck Tribune, August 9, 1935: 10.

23 Quincy Trouppe, 20 Years Too Soon: Prelude to Major-League Integrated Baseball (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1995), 53-54.

24 “Bismarck Overwhelms Twin City Giants in Final Home Game, 21-6,” Bismarck Tribune, August 12, 1935: 6.

25 “Bismarck Overwhelms Twin City Giants.”

26 Lewis E. Dial, “The Sports Dial,” New York Age, May 11, 1935: 5.

27 Dial.

28 Dunkel. 185.

29 “Capital City Nine, Undefeated in Six Starts, Is Favored,” Bismarck Tribune, August 27, 1935: 6.

30 “Great Negro Athlete Pitches Bismarck to Title,” Bismarck Tribune, August 28, 1935: 6. Official NBC records show that Paige recorded 60 strikeouts; although the number is six fewer than the Tribune reported, it is a record for most strikeouts by a pitcher in the tournament that still stood as of 2019. See nbcbaseball.com/about-us-2/history/.

31 “Bismarck Defeats Monarchs, 8 to 4,” Bismarck Tribune, September 5, 1935: 8.

32 “City Fetes Manager of Bismarck’s U.S. Semi-Professional Champions,” Bismarck Tribune, September 11, 1935: 6.

33 “Paige Versus Jones at Stadium Sunday,” New York Daily News, September 18, 1935: 120.

34 “Satchel Paige to Hurl for Kansas City Against Giants,” Chicago Defender, September 21, 1935: 13.

35 William E. Clark, “15,000 Fans See 4-Team Series at Yankee Stadium Sunday; Crawfords and Elite Gts. Win,” New York Age, September 28, 1935: 8.

36 Artie La Mar, “Fans All Het Up Over Non-Appearance of Paige at the Yankee Stadium Games Here,” New York Amsterdam News, October 5, 1935: 13.

37 La Mar.

38 La Mar.

39 Clark, 8.

40 La Mar.

41 “Dizzy’s Team Wins, 1-0: Satchel Paige Yields Three Hits,” Moberly (Missouri) Monitor-Index, October 7, 1935: 5.

42 James Newton, “Satchel Paige Stars in California Winter Loop,” Chicago Defender, November 23, 1935: 14.

43 McNeil, 179.

44 Paige, 109.

45 Paige, 110.