The Dodgers–Giants Rivalry During ‘The Era’: The Dark-Robinson Incident

This article was written by John Harris - John J. Burbridge Jr.

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

Roger Kahn coined the phrase “The Era” to represent New York City baseball from 1947 through 1957.1 During this era the Yankees won nine AL pennants and seven World Series, the Dodgers won six NL pennants and one world championship, and the Giants won two NL pennants and one World Series. While this success certainly contributed to “The Era,” another major factor was the intensity of the rivalry between the Dodgers and Giants. Perhaps no rivalry in the history of baseball created the level of ill feeling towards the opposing team as that between Giants and Dodgers fans and players, feelings which peaked during “The Era.”

Roger Kahn coined the phrase “The Era” to represent New York City baseball from 1947 through 1957.1 During this era the Yankees won nine AL pennants and seven World Series, the Dodgers won six NL pennants and one world championship, and the Giants won two NL pennants and one World Series. While this success certainly contributed to “The Era,” another major factor was the intensity of the rivalry between the Dodgers and Giants. Perhaps no rivalry in the history of baseball created the level of ill feeling towards the opposing team as that between Giants and Dodgers fans and players, feelings which peaked during “The Era.”

One particular event deserves our attention: a lightly publicized incident at Ebbets Field on April 23, 1955, between Jackie Robinson and Alvin Dark. In retaliation for close pitches by Sal Maglie, Robinson collided with Davey Williams at first base. Williams suffered a major injury to his back. Dark, the Giants captain, retaliated later in the same game. The relationship between Robinson and Dark did not end with the incident but carried into the 1960s when Dark became embroiled in a controversy over remarks concerning black and Spanish-speaking players.

THE RIVALRY

What intensifies a baseball rivalry? One factor is the proximity of the rivals, and being located in two boroughs of the same city made the distance between the Dodgers and Giants functionally zero. Dodgers and Giants fans rubbed elbows in a variety of venues throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century and half of the twentieth century. Imagine the arguments that took place in watering holes in both Brooklyn and Manhattan. One Dodgers fan killed a close friend and wounded another in a barroom in Brooklyn after being “ribbed” about the Dodgers.2

While the cities of Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and St. Louis also had two franchises for much of the same period, the distinctiveness of Brooklyn and Manhattan and what they represented created a more intense environment. Brooklyn was an independent city until 1898 when it became a borough of New York City. There was the natural divide of the East River but also a political and cultural divide. The Giants had among their fans Manhattan’s elite while Dodgers fans were mainly composed of Brooklyn’s working class.

In addition, the Dodgers and Giants were both in the National League while the other cities with two teams had a franchise in each league who rarely, if ever, met outside of exhibitions. The Dodgers and Giants played each other 22 times per year. Many of these regular season games were played with the intensity and emotion more usually found in a World Series. The rivalry dated all the way back to 1889 when the Brooklyn Bridegrooms won the American Association title and played the National League winner, the Giants, in the World Series.

Brooklyn then joined the NL in 1890 and promptly won the pennant. They also won pennants in 1899 and 1900. The Giants had to await the arrival of John McGraw as manager in 1902 to begin experiencing success. In addition to McGraw, several of his Baltimore Orioles teammates also joined the Giants. The Giants proceeded to win NL pennants in 1904, 1905, 1911–13, and 1917. The Dodgers struggled during this period until Wilbert Robinson was named manager in 1913.

Robinson and McGraw had been good friends since they were both with the Orioles. When McGraw went to New York, Robinson became the manager of the Orioles but his tenure was short-lived. In 1909 he rejoined his old friend John McGraw as pitching coach for the Giants. However, their friendship ended in 1913 when they were both critical of each other’s performance while drinking beer at the conclusion of the season. After dousing McGraw with beer, Robinson walked out of the gathering and became manager of the Dodgers in 1913.3 The rift between McGraw and Robinson certainly contributed to the intensity of the rivalry. Robinson led the Dodgers to the NL pennant in 1916 and 1920 but the Giants responded with pennants in 1921–24.

The 1930s saw Bill Terry become a player-manager for the Giants. During this decade the Giants were successful on the field while the Dodgers struggled. However, the rivalry escalated as a result of a comment made by Terry in January of 1934. When asked by a reporter about the Dodgers, Terry replied, “I haven’t heard much about the Dodgers. Are they still in the league?”4 This comment became a rallying cry for the Dodgers as they proceeded to eliminate the Giants from pennant contention, beating their rivals in the final two games of the year and giving the pennant to St. Louis.

The 1940s saw the fortunes of the two franchises change. Larry MacPhail became executive vice president of the Dodgers in 1938 and hired Leo Durocher to manage the Dodgers after the 1938 season. Durocher led the Dodgers to the NL pennant in 1941. MacPhail resigned his position in 1942 to accept a commission in the US Army and was replaced by Branch Rickey. Rickey retained Durocher as manager. During the war years the Dodgers were competitive and just missed the 1946 NL pennant, losing to the Cardinals in a playoff. The Giants under Mel Ott as manager struggled.

“THE ERA”

1947 was a turning point in the history of major league baseball because Jackie Robinson made his debut, breaking the “color barrier.” Durocher, still the Dodgers manager, was suspended for the year supposedly for actions detrimental to baseball. Under Burt Shotton, the Dodgers won the NL pennant while the Giants, finishing fourth, set a major league team record by hitting 221 home runs.

1947 was a turning point in the history of major league baseball because Jackie Robinson made his debut, breaking the “color barrier.” Durocher, still the Dodgers manager, was suspended for the year supposedly for actions detrimental to baseball. Under Burt Shotton, the Dodgers won the NL pennant while the Giants, finishing fourth, set a major league team record by hitting 221 home runs.

Durocher returned to the Dodgers in 1948 but with a slow start extending into June, Rickey was wondering whether Durocher could be the problem. Meanwhile, Giants owner Horace Stoneham was contemplating a managerial change and contacted Rickey to inquire whether he could get Durocher from the Dodgers to replace Ott. Durocher did indeed leave the Dodgers to become manager of the Giants. With the skipper jumping ship, the rivalry was sure to escalate.5

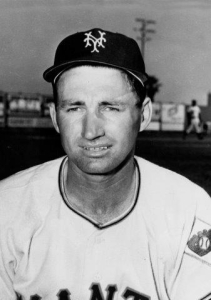

Durocher was not satisfied with the Giants’ roster. The players could hit home runs but lacked speed and fielding finesse. Durocher spent most of 1948 and 1949 trying to convince Stoneham that significant changes had to be made. Finally, during the 1949 offseason, the Giants made a blockbuster trade with the Boston Braves. They sent sluggers Sid Gordon and Willard Marshall, shortstop Buddy Kerr, and pitcher Red Webb to Boston in exchange for shortstop Alvin Dark and second baseman Eddie Stanky, two players who fit the Durocher mold.6

Stanky had previous played for the Dodgers 1944–47. He was not a great hitter but had an uncanny ability to get on base and was hard-boiled and competitive. He was supposedly bitter at the Dodgers and Durocher due to his contract negotiations in 1947.7 Rickey had shipped him to Boston. Dark, a former LSU all-star football player and Rookie of the Year in 1948, was also a fierce competitor and was coveted by Durocher.

While the Dodgers won pennants in 1949, the Giants were undergoing more changes. The Giants had acquired Negro Leagues players Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson. In addition, Sal Maglie was allowed to rejoin the Giants in 1950 with the lifting of the ban that kept former Mexican League players from playing in the major leagues.

In 1950 the bitterness of the rivalry increased. When Durocher had managed the Dodgers, he accused Carl Furillo—a Dodgers outfielder and right-handed hitter—of not being able to handle outside pitches and often platooned him.8 The animosity between the two men heightened with Durocher now the Giants manager. In a 1950 game Sheldon Jones, a Giants pitcher, hit Furillo in the head with a pitch. Furillo claimed that both Durocher and Giants coach Herman Franks had threatened him with beanballs the day before. Jones later admitted he was directed by Durocher to throw at Furillo.9 Furillo’s dislike of Durocher intensified after the beanball.

1951 saw the Giants get off to a slow start. As a result, they called up Willie Mays from their Minneapolis farm team. The Dodgers, on the other hand, were playing exceptional baseball at the beginning of the year and had early success against the Giants, sweeping them in two successive series. Don Newcombe was quoted as saying, “Me and Ralph Branca used to bang on that door after we beat them and holler, eat your heart out Leo, eat your heart out.”10 That door was the thin door that separated the visitors and home team clubhouses in center field of the Polo Grounds. After the Dodgers won on August 9, the Giants could once again hear the Dodgers singing, “Roll out the barrels. We’ve got the Giants on the run.”11

Unfortunately for the Dodgers, the Giants made them regret such shenanigans by winning 37 of the last 44 games, erasing a 13½ game lead and forcing the three-game playoff that culminated in Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.” His three-run home run in the bottom of the ninth gave the Giants the 1951 pennant. (Later the Giants were found to have used a telescope from their center field clubhouse, possibly tainting their victory, although Thomson denied getting information on Branca’s pitches.12)

The Dodgers rebounded, winning pennants in both 1952 and 1953, but a Labor Day weekend game on September 6, 1953, illustrated the hostility between Furillo and Durocher. Furillo, after going 4-for-4 in the previous game, was hit by Giants pitcher Reubén Gómez. As he was going to first base, Furillo heard Durocher heckling him and charged the Giants dugout, getting Durocher in a chokehold that caused Leo’s face to change colors.13 As Furillo and Durocher were separated, a Giants player stepped on Furillo’s hand, breaking a bone. Furillo was out for the season but still won the batting title.

1954 was a Giants year as they won the pennant and then swept the Cleveland Indians in the World Series. Leo had finally managed a team to a world championship.

THE DARK-ROBINSON INCIDENT

As the 1955 season began, the Giants and Dodgers were both favorites to contend for the National League pennant. On Saturday, April 23, the Dodgers were playing the Giants at Ebbets Field with Maglie pitching for the Giants and Carl Erskine for the Dodgers. True to form, the “Barber” Maglie began the game pitching inside to Dodgers hitters and then following up with an outside curveball, his best pitch. In the second inning, Maglie threw a pitch behind Jackie Robinson’s head. When Robinson returned to the dugout Pee Wee Reese instructed Jackie, “When you come up, drop one down the first base line and dump him on his butt.”14

As the 1955 season began, the Giants and Dodgers were both favorites to contend for the National League pennant. On Saturday, April 23, the Dodgers were playing the Giants at Ebbets Field with Maglie pitching for the Giants and Carl Erskine for the Dodgers. True to form, the “Barber” Maglie began the game pitching inside to Dodgers hitters and then following up with an outside curveball, his best pitch. In the second inning, Maglie threw a pitch behind Jackie Robinson’s head. When Robinson returned to the dugout Pee Wee Reese instructed Jackie, “When you come up, drop one down the first base line and dump him on his butt.”14

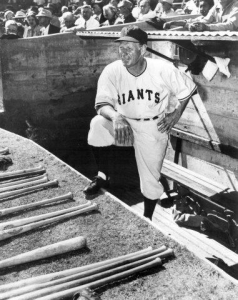

As the Dodgers came to the plate in the bottom of the fourth, Roy Campanella was the first batter and Robinson second. Campanella was a strikeout victim after being knocked down by an inside Maglie pitch. Robinson decided to take Pee Wee’s advice and lay down a bunt up the first base line intending to either knock Maglie down while fielding the bunt or, if Maglie covered first base, knock him down there. However, Maglie knew very well of Robinson’s intentions.15 Maglie let Whitey Lockman, the Giants first baseman, field the bunt. Davey Williams, the second baseman, headed to first to record the putout. Williams took a rather circular route to first, arriving in time to field Lockman’s throw but putting him directly in Robinson’s path as he crossed the base. Robinson charged into Williams, knocking him to the ground. Giants players rushed to the site of the collision and Alvin Dark, the Giants captain and shortstop, ran directly to Robinson and can be seen yelling at Robinson in a news photo of the aftermath.16

After the inning, while the Giants were in the dugout, Durocher, the coaches, and the Giants players were in agreement that they had to retaliate. There are several versions of what occurred in the dugout. One version is that Durocher was concerned how his black ballplayers felt about going after Robinson. Supposedly, he polled Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson and they told Leo to go get Robinson, he had hurt a teammate.17 Another version has Alvin Dark, the Giants captain, vowing revenge for Robinson’s role in the collision.18

Dark would bat third in the fifth inning. The first two batters made out and then Dark hit a line drive into the left-field corner of Ebbets Field for a sure double. But Dark didn’t stop at second base. Dark, a former football player at Louisiana State University, headed to third base at full speed knowing that Robinson, the Dodgers third baseman and also a former football player, would have the ball well before he could arrive. Dark was determined to barrel into Robinson in retaliation for the earlier collision, also hoping to jar the ball loose. The collision occurred and Dark successfully upended Robinson and the ball did come loose for a Robinson error. Dark was safe at third.

All 32,482 spectators and the Giants and Dodgers players wondered how Robinson would react.19 Jackie got up off the ground, collected the ball, and told Dark he would get even with Dark at shortstop. Herman Franks, the Giants third base coach, commented to Dark that he was crazy to do something like that while playing in the Dodgers’ home ballpark, Ebbets Field.20 The game continued. Dark was stranded at third base and the Giants lost, 3–1. The significant casualty was Davey Williams whose back was further damaged by the collision. He retired at the end of the 1955 season. Maglie was criticized for not covering first base and later refused to discuss the incident.21 Robinson expressed some remorse and questioned why such hatred between two teams should exist.22

The remainder of “The Era” belonged to the Dodgers as they won both the pennant and World Series in 1955 and the National League pennant in 1956. Leo Durocher left the Giants at the end of 1955. Durocher’s exit as Giants manager removed a major target of the Dodgers’ hostility. During the 1956 season Alvin Dark was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in a blockbuster deal. At the end of the 1956 season, the Dodgers then traded Jackie Robinson to the Giants for Dick Littlefield but Robinson retired. The end of “The Era” was rapidly approaching.

NINE YEARS LATER

After refusing to become a Giant, Jackie Robinson joined Chock-Full-O-Nuts as a Vice President. Dark was finally reunited with the Giants at the end of the 1960 season after playing for both the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies. Dark was then named manager for the 1961 season.He led the Giants to the pennant in 1962. But 1963 was a disappointment, as the Giants finished third and the beginning of 1964 was no better. In a trip east to play the Mets in August 1964, Stan Isaacs of Newsday asked Dark about the Giants’ troubles and he supposedly said, “We have troubles because we have so many Negro and Spanish-speaking players on this team. They are just not able to perform up to the white players when it comes to mental alertness.”23 On the Giants roster were Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Orlando Cepeda, Felipe Alou, Matty Alou, and Jose Pagan, all of whom contributed significantly in the pennant-winning year of 1962. Obviously, such a statement caused significant controversy, but guess who came to Dark’s defense? Jackie Robinson. Robinson was quoted as saying, “I have known Dark for many years and my relationships with him have always been exceptional. I have found him to be a gentleman and, above all, unbiased.”24 This was somewhat surprising given that Dark and Robinson were not close friends. Since the incident in 1955, they probably only saw each other at charity golf events.

Regardless of Robinson’s words of support, Dark’s days as the Giants skipper were numbered. Stoneham fired Dark at the end of the 1964 season. Dark weathered the controversy and later helmed the Cleveland Indians, San Diego Padres, and the Athletics in both Kansas City and Oakland.

CONCLUSION

The intensity of the Giants-Dodgers rivalry between 1947 and 1957 was possibly greater than any other in the history of baseball. Leo Durocher leaving the Dodgers in 1948 and joining the Giants intensified the rivalry. Sal Maglie’s fiery personality and penchant for pitching inside was another contributing factor. The feud between Durocher and Furillo which began in Brooklyn and erupted on several occasions illustrated the animosity between the teams. This hostility between the two franchises came to a head in the collisions of April 13, 1955. But given Durocher’s resignation at the end of 1955, Robinson’s retirement, and the subsequent moves of the Giants and Dodgers to the West Coast, the feelings that sustained the rivalry diminished. “The Era” had come to an end.

JOHN J. BURBRIDGE JR. is Professor Emeritus at Elon University where he was both a dean and professor. While at Elon he introduced and taught Baseball and Statistics. A native of Jersey City, he authored “The Brooklyn Dodgers in Jersey City” which appeared in the “Baseball Research Journal,” and has presented at SABR conventions and the Seymour meetings. He is a lifelong New York Giants baseball fan (he does acknowledge they moved to San Francisco). The greatest Giants-Dodgers game he attended was a 1–0 Giants’ victory in Jersey City in 1956. (Yes, the Dodgers did play in Jersey City in 1956 and 1957.) John can be reached at burbridg@elon.edu.

JOHN R. HARRIS is a writer, photographer and the Senior Producer of the B&H Photography Podcast. In addition to writing on baseball history, he has written extensively on photography and camera technology. His photographs have appeared in the “New York Times” and have been exhibited at the International Center of Photography, Museum of Modern Art, and Victoria and Albert Museum. A lifelong Indians fan, he had a short stint with the baseball team of his alma mater, Fordham University. John can be reached at harrisfoto@gmail.com or @jrockfoto10 on Twitter.

NOTES

1 Roger Kahn, The Era 1947–1957 When the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers Ruled the World (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press 1993), 1.

2 “Man Slew Friend in a Baseball Row,” The New York Times, July 14, 1938.

3 Alex Semchuk, SABR BioProject Biography of Wilbert Robinson, http://sabr.org/bioproje/person 5536caf5

4 Fred Stein, SABR BioProject Biography of Bill Terry, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/4281b131

5 John Drebinger, “Durocher to Manage Giants; Ott Quits; Shotton to Dodgers,” The New York Times, July 17, 1948.

6 https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/1949-transactions. shtml

7 Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 1975) 273–77.

8 Roger Kahn, The Era 1947–1957 When the Yankees, Giants and Dodgers Ruled the World (Lincoln, Nebraska; University of Nebraska Press 1993), 228.

9 Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer (New York, Harper and Row, 1972), 338–39.

10 Jim Caple, ESPN Classic, “1951 was a season for the ages,” October 8, 2001, http://espn.go.com/classic/s/2001/0927/1255904.html

11 Ibid

12 Joshua Harris Prager, “Was the ’51 Giants Comeback a Miracle, or Did They Simply Steal the Pennant,” Wall Street Journal, January 31, 2001, https://www.wsj.com/ articles/sb98089644829227925

13 Roger Kahn, The Era 1947–1957 When the Yankees, Giants and Dodgers Ruled the World (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 314.

14 Judith Testa, Sal Maglie (DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007), 245–46.

15 Judith Testa, Sal Maglie (DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007), 246–247.

16 Joseph M. Sheehan, “Dodgers Defeat Giants, 3–1,” The New York Times, April 24, 1955, S1.

17 Judith Testa, Sal Maglie (DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007), 248.

18 Alvin Dark & John Underwood, When in Doubt, Fire the Manager (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1980), 49.

19 Joseph M. Sheehan, “Dodgers Defeat Giants, 3-1,” The New York Times, April 24, 1955, S1.

20 Alvin Dark & John Underwood, When in Doubt, Fire the Manager (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1980), 50.

21 Judith Testa, Sal Maglie (DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007), 247.

22 John P. Rossi, A Whole New Game: Off the Field Changes in Baseball 1946–1960 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1999), 152.

23 Steve Travers, A Tale of Three Cities: The 1962 Baseball Season in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2009), 213.

24 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays The Life, The Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010), 420.