Newark Peppers team ownership history

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

On April 16, 1915, an overflow crowd jammed newly constructed Harrison Park to witness a historic event: the home opener of the Newark Peppers of the Federal League, the first major-league club based in New Jersey in more than 40 years. And, sadly to Garden Staters, the last. When the renegade circuit disbanded the following winter, the club was among those forsaken in the ensuing redistribution of major-league team ownership rights.

The history of baseball in New Jersey stretches back almost as far as the game itself.1 In June 1846, the first widely recognized (if mistakenly so) game of baseball was played by two New York City nines in Hoboken, New Jersey.2 Thereafter and through the 1860s, New Jersey developed its own ballclubs, with notable teams playing in Newark, Jersey City, Orange, Camden, New Brunswick, Irvington, and elsewhere. Two years after the professional National Association was founded in 1871, the Resolutes, a club from the New Jersey port city of Elizabeth, paid the $10 admission fee and entered NA ranks. Captained by catcher Doug Allison, previously a member of the celebrated unbeaten Cincinnati Reds of 1869, the ballclub had had some local success. But the Elizabeth Resolutes proved hopelessly overmatched by NA competition, and with its record standing at a woeful 2-21 (.087) in mid-July of 1873, the club abandoned play.

With most of its dense population situated somewhere along the 90-mile corridor between New York City and Philadelphia, then the nation’s two largest cities, New Jersey was not a viable site for a team of its own in the new National League of 1876. But its more relaxed blue laws held their attractions. Unlike neighboring New York and Pennsylvania, New Jersey did not prohibit the playing of professional baseball on Sunday, the only full day of leisure accorded the middle and working classes that the NL was trying to cultivate.3 As early as 1877, National League clubs from St. Louis and Hartford played lucrative Sunday exhibition games in New Jersey against local semipro teams. A decade later, the Philadelphia Athletics of the major-league American Association played random Sunday games in the New Jersey suburb of Gloucester City. Finally, on September 18, 1898, New Jersey provided the diamond for an official regular-season game between National League teams, the New York Giants defeating the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, 7-3, on the Weehawken Cricket Grounds. Thereafter, the Giants, Dodgers, and later the American League New York Highlanders played the odd Sunday game in the Garden State.4 But for the most part, New Jersey fans could only get their fill of pro baseball by following the top-tier minor-league clubs that called Newark, Jersey City, Trenton, and Paterson home.

In early 1913, the events that returned major-league baseball to New Jersey commenced, improbably, with the formation of a new, independent minor league of mostly Midwestern clubs: the Federal League.5 A year later, the fledgling circuit expanded eastward to place teams in Brooklyn and Baltimore, and audaciously declared itself a major league. Outside of Organized Baseball and not a signatory to the National Agreement, the FL disregarded the reserve clause in major-league player contracts and went about signing National and American League players. But with a few exceptions (most notably Joe Tinker, Hal Chase, and a fading Three Finger Brown), Federal League rosters consisted largely of untested youngsters, journeymen, and past-their-prime veterans. The outlaw circuit managed to complete the 1914 campaign intact, but just barely. None of the FL ballclubs turned much of a profit, and several, including the pennant-winning Indianapolis Hoosiers, were in serious financial difficulty by season’s end.

Enter 37-year-old Harry Sinclair. The ambitious Sinclair had been dabbling in minor league ballclub ownership for almost a decade as he amassed a fortune in the oil business.6 Now a multimillionaire, Sinclair deemed himself ready to upgrade his status in the game. But previous overtures about acquiring a major-league team, most notably the National League St. Louis Cardinals, had been fruitless. So in late 1914, Sinclair set his sights on the money-troubled Federal League. Quietly assisted by Federal League bigwigs in anxious need of the monetary transfusion that would attend the oil tycoon’s joining their ranks, Sinclair initially moved on the near-bankrupt Kansas City Packers. But his takeover of the KC club was stymied by a court injunction obtained by incumbent club investors. Sinclair had better luck with the Indianapolis Hoosiers, insolvent despite the club’s capture of the 1914 Federal League pennant. With behind-the-scenes assistance from FL President James A. Gilmore, Sinclair managed to acquire the Indianapolis franchise for about $81,000.7 Visions of relocating the club to New York City, however, were dashed when agents of New York Giants boss Harry N. Hempstead stealthily encumbered the Manhattan real estate needed for erection of a Federal League ballpark there.

With the 1915 season looming on the horizon and with his new ballclub without a home, Sinclair turned for counsel to baseball mentor Patrick T. Powers, already an investor in his venture.8 A veteran minor-league executive and a successful winter sports promoter, Powers proposed a solution that gratified both his home-state loyalties as a proud New Jerseyan9 and his desire to pay back fellow executives who had engineered his humiliating ouster as Eastern League president in December 1910: placement of the Sinclair club in Newark. Manhattan may not have been available, Powers reasoned, but the city’s horde of baseball fans was only a short train ride from Newark and likely to flock to the Sunday ballgames that New York City blue laws prohibited from being played in Gotham. Powers also savored the consequences that presence of a Federal League club would have on the Newark Indians, the local member of the International (formerly Eastern) League.10 There was one problem, however. With Wiedenmayer’s Park, the only ample-sized baseball venue in Newark, securely leased by the Indians, there was no ballpark for the Sinclair club to move into. Nor were ballpark-suitable property lots available for purchase in heavily built-up downtown Newark.

While not within the confines of Newark, a solution to the ballpark problem resided little more than a long fly ball away. Just across the Passaic River in adjoining Harrison lay West Hudson Field, a green expanse used by local semipro football and soccer clubs. The grounds were bounded on all sides by commercial and residential properties, but could be made large enough to accommodate construction of a major-league ballpark. With the 1915 season moving ever closer and with no other local options seemingly available, Sinclair moved quickly. With the assistance of Harrison city officials, the property, located directly across from the plant of the Otis Elevator Company and less than two blocks from the Passaic River,11 was acquired by Sinclair for a guesstimated $40,000.12 Obliging city officials then vacated two small streets that ran through the ballpark construction site.13 Yet obviously, other costs attended the start-up of a new club. Indeed, Sporting Life correspondent Edward B. Gearhart placed the Sinclair investment in the Newark franchise at about $300,000 total.14

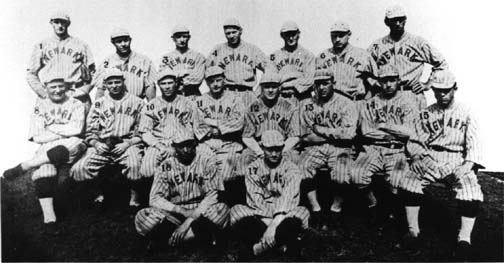

In early March, construction plans were filed with Harrison city officials, and work quickly commenced on a ballpark designed to hold over 20,000 spectators.15 Meanwhile, administrative oversight of club affairs was established. Owner Sinclair delegated day-to-day operation of the Newark franchise to club President Pat Powers, who also coined the nickname Peppers for the team.16 The other front-office positions were held by secretary Steve Harter, a holdover from the Indianapolis Hoosiers regime; business manager Billy Murray, an experienced major/minor-league operative; and treasurer O.M. Gertsung.17 The business model of the Newark Peppers has been lost to time.18 It seems reasonable to presume, however, that the franchise took the form of a closely-held corporation formed under the business-friendly laws of New Jersey, and that corporate officer positions would have been filled by club owner Sinclair, team President Powers, and other front-office executives.19 The Peppers’ field manager for the coming campaign would be Bill Phillips, the veteran skipper who had guided the Hoosiers to the FL pennant the previous season,20 while the core of the playing talent would be erstwhile Indianapolis Hoosiers, as well.

Conspicuous by their absence from the roster inherited by Newark were the names of Indianapolis’s two best players: outfielder Benny Kauff, the reigning Federal League batting champ (.370), and pitcher Cy Falkenberg, a 25-game winner in 1914. Unbeknownst to Sinclair and Powers, insolvent Indianapolis club proprietors had transferred the pair to the Brooklyn Tip-Tops that winter to settle a $10,000 debt owed Brooklyn co-owner Robert B. Ward. Once he learned, Sinclair reacted to the news furiously, threatening to walk away from his purchase of the Indianapolis club unless Kauff and Falkenberg were returned.21 This put FL President Gilmore in a tight spot. The league was in dire need of Sinclair’s investment in their operation. Yet Gilmore could not risk offending Ward, an upright man highly respected by fellow club owners and a silent financial benefactor of other Federal League clubs during the previous season. Happily for all concerned, a compromise was soon brokered whereby Falkenberg reverted to his old club, while Kauff remained with the Tip-Tops.22

With work on Harrison (aka Peppers) Park still ongoing, the Newark club began the 1915 season on the road with a 7-5 victory over the Baltimore Terrapins. After splitting the next four away contests, the Peppers boarded the train for Newark and the making of some local baseball history: the first game on home soil played by a New Jersey major-league team in more than four decades. The city pulled out all the stops for its new heroes. Newark Mayor Thomas Lynch Raymond declared the April 16 date of the Peppers’ home opener an official half-holiday, freeing city employees to leave work at noon in order to attend the mid-afternoon ballgame. Festivities began downtown, where boy scouts, local amateur baseball teams in uniform, and scores of Newark residents dressed in their Sunday finest were assembled. Led by a Scottish bagpipe and drum corps, a thousand walkers followed by automobiles, jitneys, and other vehicles festooned in celebratory bunting, then paraded across the Jackson Avenue bridge over the Passaic River to not-quite-finished Harrison Park.23

An overflow crowd, estimated at as high as 32,000,24 consumed all available viewing space, even ringing the grounds’ generous (375-425-375) playing dimensions. The game, alas, proved a disappointment for home-team rooters, as the Peppers fell to Baltimore, 6-2. The following day, Newark returned the favor, posting a 5-1 victory over the Terrapins before a respectable crowd of 5,000. But from there, Harrison Park attendance went into steep decline. An obvious cause for the attendance drop-off was oversaturation of the New York metropolitan area baseball market, there being seven high-echelon professional clubs (AL NY Yankees; NL NY Giants and Brooklyn Robins; FL Brooklyn Tip-Tops and Newark Peppers; and International League Newark Indians and Jersey City Skeeters) all playing within 15 miles of one another. Another damper on fan enthusiasm was the Peppers’ sputtering start, the team playing barely .500 ball for the first two months of the season. And suspicions lingered that Newarkers resented the fact that the new ballclub bearing their city’s name was located in another municipality.

On July 2 the International League Newark Indians, the Peppers’ most immediate competitor for fan allegiance, vacated the city, transferring operations to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Yet the departure of a local rival did not cure the cause of poor attendance identified by Peppers brass: inconvenient access to Harrison Park. Shortly thereafter, Sinclair and Powers voiced their dissatisfaction with the situation, threatening to relocate the Newark Peppers to another city unless trolley service directly to Harrison Park was instituted by the Railway Public Service Corporation.25 This led Sporting News correspondent Joe Vila to issue the sneering prediction that “the Feds will be out of New Jersey within a month.”26

Public Service promised consideration of the Peppers’ request, even proposing to lay rail tracks across the Jackson Avenue bridge to the ballpark – but ultimately did nothing. But rather than forsake Newark, club management embarked upon a promotional campaign. The already-modest Harrison Park admission prices were slashed, with bleacher seats reduced to a mere 15 cents.27 Meanwhile, Peppers games were coupled with bicycle races, track meets, and other fan attractions.28 The strain, however, evidently took its toll on Peppers executives. During a road trip to Buffalo, heated words were exchanged between club President Powers and secretary Steve Harter, who promptly resigned his position. Thereafter, business manager Billy Murray took on the club secretary responsibilities.29

Despite the front-office turmoil, the Peppers began to move up in league standings under the direction of newly installed third baseman-manager Bill McKechnie. And by August, Newark was in the thick of the pennant chase. Improvement in the team’s fortunes crested on August 22, when a near-capacity 20,000 crowd saw the Peppers assume first place by sweeping a Harrison Park doubleheader against the Pittsburgh Stogies. The club’s reign at the top, however, lasted only two days. By season’s end, a faltering finish dropped the Peppers (82-70, .526) all the way to fifth place, but only six games behind the pennant-winning Chicago Whales in tightly bunched final FL standings.

While it played the 1915 season, the Federal League was also pursuing a federal antitrust-type lawsuit against Organized Baseball. That August, however, discreet settlement negotiations were opened, with Newark owner Sinclair assuming a major role on the FL side. Eventually an agreement was struck under which two Federal League club owners (Charles Weeghman of Chicago and Phil Ball of St. Louis) were permitted to purchase controlling interests in the NL Chicago Cubs and AL St. Louis Browns, respectively. Other FL club owners (including Harry Sinclair) received generous buyout payments in the form of compensation for expenses incurred from erection/maintenance of FL ballparks and future rental thereof by Organized Baseball. And FL club owners’ rights over players still under contract were recognized.30 With the exception of the Baltimore franchise (which pursued the case unsuccessfully up to the United States Supreme Court),31 the settlement was subsequently ratified by FL club owners, and the Federal League went out of existence in December 1915.

Although Sinclair was not one of the FL club owners authorized to purchase an available American or National League franchise, he made out quite well in the settlement.32 To compensate him for the cost of building Harrison Park, the National Commission, Organized Baseball’s governing body, approved payment of an annual $10,000 stipend to Sinclair for use of the grounds by teams in Organized Baseball for the ensuing 20 years.33 He also made money selling the contract rights to players like Edd Roush (to the Giants for $7,500) and Earl Mosley (to the Cincinnati Reds for $5,000). Those Peppers players who did not attract major-league interest were sold to minor-league clubs, or released outright.

Except for first baseman Rupert Mills, the one-man Federal League of 1916. A four-sport letterman and a recent graduate of the University of Notre Dame, Mills had been a schoolboy star at Newark’s Barringer High School and was thought to be just the kind of hometown celebrity needed to bolster flagging attendance at Harrison Park. Days after Mills received his pre-law bachelor’s degree, the Peppers signed him to an ironclad two-year, $3,000-per-season contract. Regrettably, Mills proved a bust, batting a meager .201 in a 41-game FL audition with shaky infield defense. When neither major- nor minor-league clubs expressed interest in Mills over the winter, club President Powers attempted to release him with a $500 severance payout. But Mills was having none of it. He had a guaranteed $3,000 contract for the 1916 season and he expected to get paid by the Peppers, whether the Federal League existed or not.

Wary of locking horns in court with the legally trained ballplayer – Mills would go on to a career of political prominence in New Jersey before dying in a 1929 boating accident34 — Powers settled upon an alternate course. He would demand specific performance of contract terms by Mills. But to Powers’ astonishment, and then chagrin, Mills was perfectly agreeable, showing up five mornings a week to play eight hours of solitaire baseball in otherwise deserted Harrison Park. When word of Mills’ antics spread, reporters flocked to the grounds to see the show, and then hear its featured (and sole) actor regale them with tales of how he pitched to himself (mostly curveballs); beat out grounders hit to himself at shortstop, and hustled over to umpire close plays at first base. (He was always safe.) Soon, the Harrison Park comedy was receiving newspaper ink from coast to coast. Embarrassed, Powers threw in the towel and paid off the wily Mills in mid-June.35

The shuttering of the Rupert Mills show rang down the curtain on the Newark Peppers. And on New Jersey as home to a big-league baseball club.36 Now more than a century has passed, and the ballclub is beyond living memory. Rarely considered more than a footnote in the twentieth-century history of the game, the Newark Peppers retain at least one distinction – the placing, albeit briefly, of the Garden State on the major-league landscape.

BILL LAMB spent more than 30 years as a state/county prosecutor in New Jersey. He is the editor of “The Inside Game,” the newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee and the author of “Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation” (McFarland, 2013). He is also the 2019 recipient of the Bob Davids Award, SABR’s highest honor.

Sources

Much of the text above has been drawn from the author’s previous writings on the Newark Peppers, mostly published in The Inside Game, the newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee. The underlying sources of specific passages in this piece are provided in the endnotes. Sources on the Federal League include Daniel R. Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Lanham, Maryland: Ivan R. Dee, 2012); Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs: The History of an Outlaw Major League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010), and Marc Okkonen, The Federal League of 1914-1915: Baseball’s Third Major League (Garrett Park, Maryland: SABR, 1989).

Notes

1For a complete general history, see James M. DiClerico and Barry J. Pavelec, The Jersey Game: The History of Modern Baseball from Its Birth to the Big Leagues in the Garden State (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1991). For meticulously researched detail on specific New Jersey ballclubs and events, consult A Manly Pastime, the blog of John G. Zinn, the preeminent authority on early baseball in the Garden State.

2 The four-inning contest saw a hastily assembled team styled the New York Base Ball Club trounce the venerated Knickerbockers, 23-1. The venue was Elysian Fields, a popular Hudson County resort located a short ferry ride across the Hudson River from lower Manhattan.

3 During the late nineteenth century, the only National League locations that permitted Sunday baseball were Chicago, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, heavily German immigrant cities without the Puritan lineage and traditions of the East Coast.

4 As per DiClerico and Pavelec, 49-53.

5 For complete histories of the Federal League, see Daniel R. Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Lanham, Maryland: Ivan R. Dee, 2012), and Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs: The History of an Outlaw Major League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010). Tables of FL club organization, ballpark schematics, and other particularized data are provided by Marc Okkonen in The Federal League of 1914-1915: Baseball’s Third Major League (Garrett Park, Maryland: SABR, 1989).

6 Sinclair’s initial foray into baseball club ownership occurred in 1906 when he and co-owner M.L. Truby acquired the Independence franchise of the Class D Kansas State League. For a contemporary portrait of Sinclair, see F.C. Lane, “Famous Magnates of the Federal League,” Baseball Magazine, Vol. 15, No. 4, August 1915.

7 Per Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball, 201-202.

8 The amount of Powers’ contribution is unknown, but according to his birthplace newspaper, Powers “had invested more money in the Federals than any other resident of New Jersey ever had in a similar enterprise,” per “Sees Fine Future Ahead for Feds,” Trenton Evening Times, February 15, 1915. As Sinclair was easily the wealthiest investor in the Federal League, he hardly needed Powers’ money. But Sinclair esteemed his baseball expertise.

9 The 54-year-old Powers was born in Trenton and got his feet wet as a baseball executive by managing minor-league clubs in Trenton and Jersey City. For more on Powers, see his informative BioProject profile by Charlie Bevis (BioProject node 3922). For most of his adult life, Powers was a Jersey City resident.

10 The year after Powers was removed as Eastern League president, the circuit changed its name to the International League.

11 A Harrison street grid showing the location of the new ballpark is provided in Okkonen, The Federal League of 1914-1915, 59.

12 Joe Vila, “Vila Draws Dark Picture for Feds,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1915.

13 Per “Official Announcement of Newark Federal Club,” Trenton Evening Times, February 25, 1915.

14 See Edward B. Gearhart, “Newark Nuggets,” Sporting Life, June 15, 1915. New York sportswriter Joe Vila’s estimate was $231,000. See again, The Sporting News, April 1, 1915.

15 For more detail on the life and death of the Newark Peppers’ ballpark, see Bill Lamb, “Harrison Park,” The Palaces of the Fans (the newsletter of SABR’s Ballparks Committee), Summer 2019: 16-22.

16 Per Frank G. Menke, “Hot Liners,” Stamford (Connecticut) Advocate, and “Newark Feds Called Peppers,” Watertown (New York) Times, March 15, 1915. Supposedly, Powers thought that the Newark players displayed a lot of “pep” in early preseason workouts.

17 Per Okkonen, The Federal League of 1914-1915, 42.

18 Incorporation and related documents would have been filed with the office of the New Jersey secretary of state, but a check of state archives failed to uncover such documents. Many thanks to John Zinn and state archivist Donald F. Cornelius for undertaking the document search for the writer.

19 Instructive here is the example of the New York Giants, a closely held New Jersey corporation officially known as the National Exhibition Company and holding its corporate meetings in Jersey City.

20 Prior to the 1915 season, Giants manager John McGraw allegedly turned down a $100,000 offer from Harry Sinclair to take over the Peppers. See Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (New York: Viking Penguin, 1988), 182. Thus, Phillips, who had guided Indianapolis to pennants in both 1913 and 1914, remained in command in the dugout.

21 As reported in “Feds in Tangle,” Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette; “Feds Fuss Over Two Players,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and elsewhere, March 25, 1915.

22 As reported in “Kauff to Join Tip Tops,” Baltimore Sun, March 27, 1915; “Kick by Sinclair Gets Falkenberg for Him,” New York Sun, March 27, 1915, and elsewhere.

23 Per Bill Lamb, “April 1915: The Newark Peppers Return Major League Baseball to the Garden State,” The Inside Game, Vol. XVIII, No. 4, September 2018, 25. Sections of the roof over grandstand seating remained incomplete.

24 When completed, Harrison Park would seat about 21,000 spectators. For the Peppers’ home opener, a crowd of 32,000 was estimated in a headline published in the Newark Evening News, April 17, 1915. The New York Times, meanwhile, guesstimated the game’s attendance as 25,000. Modern authorities such as Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet provide a specific attendance figure of unknown origin: 26,032.

25 See “Feds Blame Trolleys,” New York Times, July 9, 1915, and “Federal League Affairs and Matters,” Sporting Life, July 17, 1915.

26 Joe Vila, “Newark a White Elephant for Feds,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1915.

27 See “15 Cent Ball at Newark,” New York Times, August 3, 1915, and Joe Vila, “Gilmore Adds to Broadway Gaiety,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1915.

28 Peppers President Pat Powers had introduced the six-day bicycle race to Madison Square Garden some 20 years earlier and had long experience in athletic promotions.

29 As reported in “A Business Manager [sic] Resigns,” Kansas City Star, July 15, 1915.

30 For a comprehensive exposition of the negotiations and settlement, see Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball, 223-233.

31 Baltimore’s pursuit of the litigation ultimately resulted in the exemption from federal antitrust statutes granted to Major League Baseball by the United States Supreme Court in Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League, 259 U.S. 200 (1922).

32 Thereafter, Sinclair would spend the better part of 1916 in fruitless negotiation with club boss Harry N. Hempstead regarding purchase of the New York Giants.

33 See James F. Greavey, “Knockers Do Not Die with Outlaws,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1916. See also, Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball, 228-229. A similar arrangement was reached with the Ward brothers granting them an annual $20,000 “rental” payment for the Brooklyn Tip-Tops’ former ballpark. Regarding Harrison Park at least, MLB hoped to offset part of the Sinclair stipend through sublease of the grounds to a Newark-area minor-league club.

34 Then undersheriff of populous Essex County and prepping for a run for New Jersey governor, Mills suffered an apparent heart attack and drowned in a summer resort lake while attempting to rescue a nonswimming occupant of a capsized canoe.

35 For a biographical profile of Mills complete with more detail on his solo performances at Harrison Park, see Bill Lamb, “Rupert Mills: The One-Man Federal League of 1916 – And a Great Deal More Than Just Another Obscure Deadball Era Ballplayer,” The Inside Game, Vol. XVIII, No. 3, June 2018, 28-36. The Mills show ran for 65 performances before closing, per Al Kermisch, “Researcher’s Notebook Unravels Mysteries: Mills Kept Federal Loop Alive in ’16,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 15 (1986): 3-4.

36 During the 1956 and 1957 seasons, the Brooklyn Dodgers played a handful of “home” games at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City. But the Dodgers have never been considered a New Jersey team.