SABR Official Scoring Committee: October 2020 newsletter

“You Called That a What . . . ?”

The Newsletter of the Official Scoring Committee

Society for American Baseball Research (SABR)

October 2020, Volume 6, Number 1

Editor:

Stew Thornley

- From the Co-Chairs

- Conundrums of the Month (or Quarter or Whatever)

- Profile: Mel Franks

- It Finally Happened: A Four-Base Over-the-Fence Error

- Bloops and Bobbles

- Honchos

From the Co-Chairs

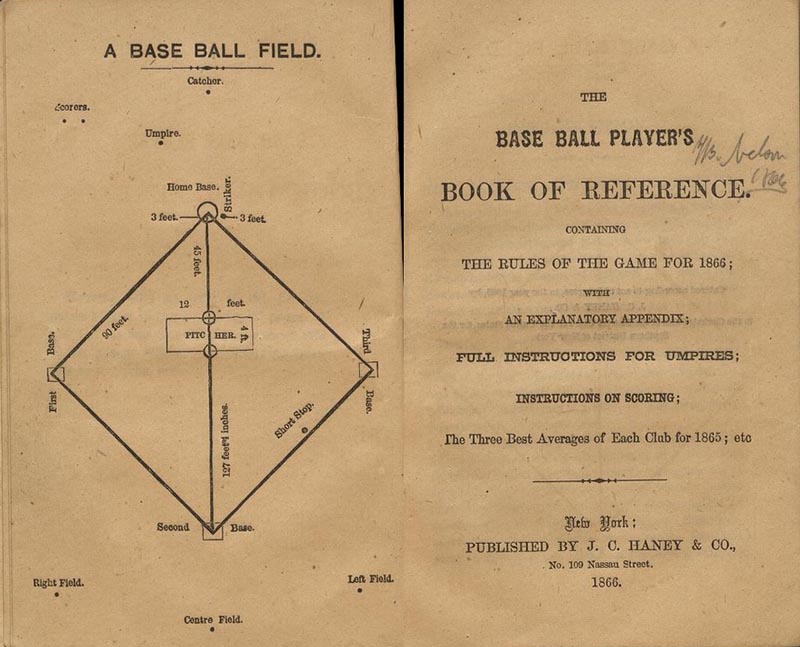

Among lots of strange goings-on this year, the 2020 season is perhaps the first time in professional baseball history that the official scorers had to do their job “from home,” just like many of us. This marked a historic departure, as the ability of scorers to see the game in person was once assumed to be critical to facilitating their judgment. The first scorers in baseball, in fact, were assigned to do their job from the field near the catcher and umpire, as the frontispiece to Henry Chadwick’s 1866 manual indicates.

Of course, as official scorers were informally and eventually formally drawn from the ranks of newspaper reporters, their typical location moved to the press box. It wasn’t a matter of requirement, just convenience. Only in 1957 were the rules changed such that it was clear that the correct position of the official scorer was the press box, facilitating the public announcement of each play’s scoring. Until 2020, even with the ability to use video replay after the fact, scorers were required to make their initial calls from the press box.

We might think of doing some interviews with current scorers after this season to see what, if any, difference scoring from “home” might have made, whether or not scorers return to the press box next year. Another potential historical record from our pandemic year.

—Chris Phillips

From the other co-chair:

As usual, keep an eye on our Committee Files page, as the information in there continues to grow.

The Links to Stories category has links to articles on Gary Mueller and Ben Trittipoe and how they are doing official scoring from home this season. There is also a link to The Sporting News of October 20, 1962 and a column by Dan Daniel in which he apparently endorses the idea that the first hit of a game must be a “genuine, authentic, 100 per cent specimen.” This column is also reprinted in the Articles file in the Committee Files page. Another article in this file (thanks to Sarah Johnson for sending it along) is by Shirley Povich on official scoring in 1978. Povich talks about the controversy of Bob Forsch’s 1978 no-hitter, the practice of newspapers to stop allowing their writers to be official scorers, and Paul Waner getting an official scorer to change a call from hit to error on what would have been Waner’s 3,000th hit in 1942.

A new SABR Century Research Committee is looking to other research committees to do research projects from 100 years before. Nothing comes to mind for 1921, but 2022 will be the 100th anniversary of a controversy that allowed Ty Cobb to have a batting average of over .400. John Kieran, the official scorer, called an error on New York shortstop Everett Scott; however, Fred Lieb, in filing the box score for Associated Press, had the play as a hit for Cobb, and the American League used Lieb unofficial judgment in awarding Cobb a hit. If anyone is interested in researching this for an article or game story, please let me (stew@stewthornley.net) know. One for 2023 could be Howard Ehmke’s no-hitter of September 7, 1923. Twice it looked like his no-hitter was gone — once when Slim Harriss apparently doubled in the sixth inning but was called out for missing first, and the other time when Frank Welch hit a low liner to center in the eighth that Mike Menosky could not catch. The official scorer called it a hit but later, after consultation with the players, changed the call to an error on Menosky.

See Bloops and Bobbles below for more ideas on possible research projects.

Finally, Caleb Thielbar may never be charged with a loss like he got on September 27, 2020. Pitching for the Twins against Cincinnati, Thielbar faced four batters and retired all of them: Mike Moustakas on a ground ball to Miguel Sano, Shogo Akiyama on a strike out, Jesse Winker on a fly out to Eddie Rosario, and Freddy Galvis on a pop up to Jorge Polanco. However, he faced Galvis to start the 10th inning, and Michael Lorenzen (running for Winker) was on second. Lorenzen and others scored when Sergio Romo relieved Thielbar and gave up two hits and two walks. Lorenzen’s run was charged to Thielbar, making him the losing pitcher. Unless baseball retains its extra-innings rule, no losing pitcher will end up with a line like this again.

Conundrum of the Month (or Quarter or Whatever)

How Can a Pitcher Get a Shutout but Not a Complete Game?

Rule 9.18: A shutout is a statistic credited to a pitcher who allows no runs in a game. No pitcher shall be credited with pitching a shutout unless he pitches the complete game, or unless he enters the game with none out before the opposing team has scored in the first inning, puts out the side without a run scoring and pitches the rest of the game without allowing a run. When two or more pitchers combine to pitch a shutout, the league statistician shall make a notation to that effect in the league’s official pitching records.

No such exception (entering the game with no out in the first inning) exists for a complete game. SABR member Ian Orr pointed out that Neil Allen was credited with a shutout but not a complete game for the Yankees on May 31, 1988:

New York Yankees 5, Oakland Athletics 0

Carney Lansford led off the last of the first for a line drive that hit Al Leiter’s left arm and caromed into his thigh. Leiter corralled the ball and threw wide of first, allowing Lansford to get to second on a hit and an error. Allen relieved, got out of the inning, and pitched eight scoreless more.

Could a Team Lose a Perfect Game?

It didn’t but it could have happened in the major leagues this year. If a team’s pitchers retire all 27 batters through nine innings but their hitters haven’t scored, the game goes into the 10th inning with the opposing team having a runner on second base. If that runner comes around to score, without anyone else reaching base, is it considered a perfect game?

Traditionally, a perfect game as been considered to be one in which no one reaches base. A special records committee in 1991 developed a definition for no-hitters/perfect games, although that dealt with such games that were fewer than nine innings and with no-hitters through nine innings that were broken up in extra innings. Because of this, Harvey Haddix’s perfect game was removed from the rolls of “official” no-hitters/perfect games.

But the committee’s definition did not address the issue of a runner being automatically placed on second. This question came up in the minor leagues in 2018, Tampa Tarpons Lose Perfect Game to Extra-Inning Rule.

Cory Schwartz of MLB.com issued this directive: “Auto-runners don’t count against a perfect game or no-hitter. ”

So it could have happened.

Another question that often comes up is can a team be charged with an error in a perfect game? For example, if a batter hits a foul fly or pop up that is dropped for an error and that batter is then put out, would that affect the status of a perfect game? The answer is no. A perfect game is defined as no runner reaching base. Such an error would not affect it.

Profile: Mel Franks

On Friday, July 13, 1979, a national audience watched as Nolan Ryan went for what would have then been his fifth no-hitter. In the eighth inning came a play that official scorer’s hope to avoid (see On the Hot Seat: No-Hitters and Official Scorers). The result was a change in who did the official scoring in Los Angeles. Mel Franks, a current official scorer for Angels and Dodgers games, got his start because of this.

In Mel’s words:

I was recruited by the then California Angels to score their home games in 1980 after a controversial call the previous season signaled the beginning of the end of the tradition of members of the Baseball Writers Association of America performing the task.

It was a Friday the 13th evening in July 1979, with the New York Yankees visiting a nearly sold-out Anaheim Stadium for a special edition of Monday Night Baseball broadcast nationally on ABC. Nolan Ryan was bearing down on a historic fifth no-hitter in the eighth inning when Jim Spencer, a former Angel, hit a sinking line drive to center field. Rick Miller made a lunging attempt at a shoestring catch but the ball bounced off the heel of his glove and Spencer reached second base. Dick Miller, no relation, of the Herald-Examiner, promptly ruled the play an error. Equally quickly, protestations arose from the Yankees’ dugout, Angels GM Buzzie Bavasi and, most vociferously, Howard Cosell, who pontificated about the provincialism of the call. The discussion of the dual role of the writers continued even after Reggie Jackson, a future Angel, singled up the middle with one out in the ninth.

Editors of the metropolitan Los Angeles newspapers wanted their reporters covering the news, not making it, so they put a stop to the practice, leaving the teams to find replacement scorers. I had worked in the Angels’ public relations department from 1973 through 1978 so I was a known quantity, had seen at least 100 games in person each year (which was an unwritten standard for the writers), and was available.

But in August of 1980 I took a job as the sports information director at Cal State Fullerton. I finished the Angels’ season but it was obvious the overlapping schedules weren’t compatible for full-time duty, so for 1981 the Angels turned to Ed Munson, another former PR guy. He went on a Cal Ripken Jr. streak, working 2,000 consecutive games before MLB sought to create a pool of scorers beginning in 2006. Angels VP Tim Mead, now director of the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, called. I had remained active in baseball thanks to Fullerton’s nationally prominent program, which would eventually take me to 28 NCAA Tournaments, including 14 College World Series. And I was available again since the university had dropped football. I have averaged about 15 games per year plus did about a dozen Dodgers games in 2018.

Interesting situations:

In 1980, Angels manager Jim Fregosi would often call the press box during the game to offer “insight” into a situation or, more likely, “critique” a call. Now there is no direct contact allowed and an appeal process is in place based on video highlights.

Also in 1980, I often was a “stringer” for AP and/or UPI and would have to go to the clubhouse for post-game quotes—with a target on my back for disgruntled players. Nothing serious ever developed and the most memorable exchange was with second baseman Bobby Grich, who actually asked that an opponent’s hit be changed to an error on him. That seldom happened.

Since 2006, I’ve had to focus on objectivity when some of my former Fullerton players have played at the Big A. I also had to ward off devious thoughts, such as when the Angels’ Jered Weaver took a no-hitter into the ninth inning. I had seen him pitch several times for Fullerton’s archrival Long Beach State so he was a “bad guy.” Happily for everyone, he got the no-hitter when Torii Hunter went to the warning track to log the 27th out. That“s the only time I’ve had a no-hit situation reach the ninth in at least 300 games.

I still get calls from collegiate SIDs for an interpretation of a play or situation. Scoring is hard enough when you see the play, much less have to visualize it.

Advice

You better love baseball because you need to focus on every pitch, no matter the score or situation. Given the length of games nowadays, a large bladder is an asset.

Experience. Any time you watch a game pretend you are scoring to anticipate things such as runners taking extra bases, who made the relay throw, and whether a play has more than one error.

Read and re-read to rule book. As Don Drysdale use to say, “Every game you see something new. ” The recent proliferation of an “opening” pitcher has complicated determining the winning pitcher. And you might need to know the specifics of a bases-loaded catcher’s interference.

It Finally Happened: A Four-Base Over-the-Fence Error

As defined in Rule 5.05(a)(9), a batter is entitled to a home run if a fielder deflects a fair fly ball into the stands or over the fence in fair territory. But does an official scorer have the option to call a four-base error if the judgment is that the fly ball is one that could have been caught with ordinary effort? The interpretation from Elias Sports Bureau at the first-ever meeting of official scorers in 2012 was that such a judgment can be made. It took more than eight years for this to happen.

On August 9, 2020 Nick Solak of Texas hit a fly ball to right that was deflected over the fence by Angels outfielder Jo Adell. Lary Bump, the official scorer, charged Adell with an error rather than crediting Solak with a home run.

Angels Right Fielder’s Embarrassing Blunder Turned a Routine Fly Ball into a Rangers ‘Home Run’

Ever Seen a 4-base Error? Now You Have

Four-base errors have been called before on balls that have stayed in the playing field, but this is believed to be the first time such a call was made on a ball that left the playing area in the major leagues.

Such a play has happened at other levels, including in a 2017 college game between Air Force and New Mexico, as chronicled in the June 2019 newsletter of the SABR Official Scoring Committee newsletter.

Bloops and Bobbles

SABR’s 50 at 50 book has an interesting article by Keith Olbermann, Why Is the Shortstop “6”? In addition to examining this question, the article provides a good history of varying methods of scoring along with an illuminating 1950s conversation between Bill Shannon, who became a stalwart official scorer, and Hugh Bradley of the New-York American-Journal. Not only that, you’ll learn about Frink’s Eczema Ointment.

You can read the article, along with 49 others, by buying the book or going to the Baseball Research Journal archives and finding it on page 16 of Volume 34 (2005), where it originally appeared.

Bill Shannon would be a fascinating project for someone interested in writing about him for the SABR BioProject. The BioProject now has three entries for official scorers: Susan Fornoff, Gregg Wong, and Kyle Traynor. More are sought. The BioProject is determining the worthiness of official scorers to be included on a case-by-case basis. Before proceeding, check with Lyle Spatz of the BioProject. If you want to learn more about potentially interesting subjects, let me ( stew@stewthornley.net) know.

Honchos

Chris Phillips—(Co-Chair)

Stew Thornley—(Co-Chair and Newsletter Editor)

Marlene Vogelsang—(Vice Chair)

Gabriel Schechter—(Vice Chair)

Bill Nowlin—(Vice Chair)

Sarah Johnson—(Vice Chair)

John McMurray—(Vice Chair and Liaison to the Oral History Research Committee)

Art Mugalian—(Assistant to the Traveling Secretary)