Spring training pioneers: Flying the ‘Southern Clipper’ with the Cincinnati Reds

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in SABR’s “The National Pastime,” Vol. 6, No. 1, Winter 1987. To read more from the TNP archives, click here.

Cincinnati Reds GM Larry MacPhail and manager Chuck Dressen watch a spring training game in the mid-1930s. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Just over fifty years ago, on March 5, 1936, I watched the sun rise in San Pedro de Macoris in the Dominican Republic.

Today San Pedro de Macoris is famous as the birthplace of Pedro Guerrero, Joaquin Andujar, George Bell, Tony Fernandez, Pepe Frias, Rufino Linares, Julio Javier, Mariano Duncan, Julio Franco, and a host of other present and past major leaguers.

What was I doing there long before any of those players had been born? I was traveling secretary, shepherding a group of Cincinnati Reds on their way back home from an historic spring training trip to Puerto Rico.

Before 1936, no big league club had ever trained outside of the continental United States. True, the New York Giants had played a few spring exhibition games in Havana, but that was all.

Larry MacPhail, general manager of the Reds, had arranged the jaunt. We spent about a month working out in San Juan, then half the team had taken a ship to Ciudad Trujillo to play a couple of exhibition games in Dominican Republic. The rest of our trip back to the States would be by air — the first team flight in baseball history.

Few of us had ever set foot in a plane of any kind. So we were pretty nervous as we awaited the Catalina flying boat. A sereno, or hotel night watchman, had pounded on all our doors to wake us up at 4 AM. We piled into rickety taxis and were driven forty miles over winding, scary roads to our place of embarkation, a town destined to become an unbelievably fertile source of big leaguers.

Manager Charlie Dressen and many of the players had remained in San Juan and would join us later in Florida, where we would all finish our spring training in Tampa.

Charlie’s two husky coaches, George “High Pockets” Kelly and Tom Sheehan, were with us, as was veteran National League umpire Bill Klem. We also had with us the three Cincinnati baseball writers, Jack Ryder of the Enquirer, Frank Grayson of the Times-Star, and Tom Swope of the Post; the club trainer, Dr. Richard Rohde, and players Campbell, Raimondi, Scarsella, Kampouris, Riggs, Cuyler, Harvey Walker, Blakeley, Herrmann, Schott, Hollingsworth, Si Johnson, Freitas, Kahny, Brennan and Wistert. So our group totaled twenty-four men.

We tried to hide our jitters as we all stood around the dock in San Pedro de Macoris. Kelly produced a bottle of brandy to spike the black Pan American coffee. Finally we spied a silver speck on the horizon in the early morning sky. It grew larger and more brilliant. It was our big bird, called “The Southern Clipper.” It glided gracefully into the harbor without a bounce, hardly causing a ripple.

Pan American had started using these flying boats a few years earlier with commercial flights between Florida and Cuba. By now, they were flying to South America, as well as across the Atlantic and the Pacific.

MacPhail had agreed that nobody would be forced to fly against his will. He tried to reassure us that in a “flying boat” traveling over water, we would have our “landing field” beneath us at all times. Benny Frey, a right-handed pitcher, was dubious, but he didn’t raise a fuss. Gilly Campbell, our loquacious catcher, had been the last holdout. He reluctantly agreed to tag along when he saw the rest of us ready to take part in the historic event.

MacPhail had agreed that nobody would be forced to fly against his will. He tried to reassure us that in a “flying boat” traveling over water, we would have our “landing field” beneath us at all times. Benny Frey, a right-handed pitcher, was dubious, but he didn’t raise a fuss. Gilly Campbell, our loquacious catcher, had been the last holdout. He reluctantly agreed to tag along when he saw the rest of us ready to take part in the historic event.

As the clipper drew up to the dock, the skeptics among us seemed reassured by the perfect landing we had just witnessed. The baggage was loaded. We climbed on board, and soon we began cruising across the bay to takeoff position. The engines revved up, and we were off. Once in the air, it wasn’t long before we — at least outwardly — shrugged off our nervousness. Within a few minutes, Gilly Campbell was telling everybody on the plane, “This is the way to go!” Not only was he glad to be on the plane with us but he proclaimed again and again that in the future he was taking a plane wherever he went.

Somebody started a foursome of bridge and a couple of gin rummy games got under way. Others read magazines or got into bull sessions.

Tony Freitas, our left-handed pitcher who had once been with the Philadelphia Athletics, wasn’t as quickly sold on flying as Campbell was. Tony kept his face glued to the window, looking for sharks and watching the flying fish skim along the surface of the ocean. We flew low enough that we could easily see the waves and an occasional ship or small boat. Our cruising speed was 110 miles an hour, as I recall. I don’t think we ever rose higher than 1,500 feet above the water.

Normally a clipper would have accommodated perhaps a dozen passengers more than the two dozen in our group. But allowance had to be calculated for our heavy load of baseball bats, uniforms, and other athletic paraphernalia.

It took two hours to reach Port-Au-Prince, the capital of Haiti. A brief stop there enabled us to mail a few souvenir postcards. There we heard a French patois instead of the Spanish we had become accustomed to in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

We found that the flight was bumpy when we had to travel over land for short distances. But over the Caribbean and the Atlantic you could have juggled a cup brim-full of coffee without spilling a drop.

Two hours out of Port-Au-Prince we came down in Nuevitas, Cuba for our second stop. During the first two legs of the journey there had been several magazines on board. After we left Nuevitas, I asked the steward to let me see a copy of Newsweek or Time.

“We took off all the magazines before we left Cuba,” he told me. “We need to figure weight allowance very carefully so we can carry the maximum amount of fuel for the long hop to Miami.”

If they were calculating the weight of four or five magazines for a hop that couldn’t have been more than 500 miles — well, that began to shake my confidence. I wondered what it would be like if we had to ditch the clipper ship on those Atlantic waves, possibly many miles from our destination. I began to think of Tony Freitas and those sharks.

We flew on, however, without incident the rest of the afternoon, finally landing a short distance from Miami’s waterfront about 5 PM. It had been a long, arduous day. Despite our bravado, all of us were glad to plant our feet on terra firma.

We were disappointed that no newsreel cameramen were on hand to greet us. After all, they had been notified about our ETA. As an old newspaper man, I thought the trip certainly was newsworthy. Here we were, pioneers in baseball at least — and no cameras!

Next morning the newsreel people phoned me at our hotel. They apologized having missed filming our arrival by clipper ship but something or other had happened to prevent their covering the occasion. But they still wanted it for their newsreels. Would we cooperate?

Part of my job was to get publicity for the Cincinnati Reds, so I agreed to go along with their wishes. The club was due to play an exhibition game against the Philadelphia Athletics that Friday afternoon, and we were scheduled to leave the hotel at 12:30 PM. The players had to dress in the hotel because there were no accommodations for visiting players at the Miami ballpark. I agreed to have the players get ready early and to have the bus stop off at the Pan American dock on the way.

This delighted the newsreel people. When we got there, the cameramen requested that all of us get on the clipper ship. At a given signal the door opened and the fully uniformed players descended the gangplank, some with balls and gloves in their hands, others with bats, while the newsreel cameras rolled. On instructions from the newsreel people some of the players began playing catch, with the clipper ship in the background. Others started pepper games, bunting and fielding the ball in midseason form.

It was strictly ridiculous. First of all, on Thursday we had been awakened at 4 AM, Dominican time, had driven 40 miles to the place where we boarded the plane, and had flown all day, on the road or in the air probably 14 or 15 hours. That schedule had left us pretty weary by the time we reached Miami, certainly in no mood for frisking about with bats and baseballs as soon as we touched ground!

Yet the newsreels showed us emerging from the clipper ship, everyone in uniform and spiked shoes, full of energy, warming up the minute we finished that long, wearing flight. I wonder how many people who saw those newsreels detected the irony of the situation, or realized it was all simulated. But no harm was done and both Pan American and the Reds got some nationwide free publicity.

Publicity, of course, had a lot to do with the whole Puerto Rico expedition. During the winter when the plans were announced it was my job as publicity man for the team to stimulate fan interest for the 1936 season. The newspapers and radio stations were friendly and cooperative with us, but they didn’t have much manpower to dig up feature material. Cincinnatians didn’t know much about Puerto Rico except that it was an island somewhere down there southeast of Florida.

In order to keep the material flowing to the newspapers I did some research about Puerto Rico. In one of my releases to the press I revealed that there were 49,545 horses and 8,041 mules on the island, as well as 24,446 bee colonies. Cincinnatians began to wonder where in the world there would be room for baseball players with all those horses, mules, and bees crowding the place.

I also found out that there was a relatively high incidence of venereal disease among Puerto Ricans, but I shared this information only with MacPhail.

In New York, the redhead gathered a group of us in his hotel suite and lectured the players on the dangers of VD in Puerto Rico. “I will follow the practice of the army in case any of you get infected. You’ll be suspended immediately without pay, and you won’t get back on the payroll until you’re completely cured and in condition to play.”

Since the Cincinnati players lived in various parts of the United States, there were only some of the pitchers and catchers in our group, as well as manager Charlie Dressen, coaches Kelly and Sheehan, the three baseball writers, and Sue Ryder, wife of sportswriter Jack Ryder.

On the afternoon of February 6 our little party boarded the SS Borinquen in New York Harbor along with a few hundred passengers headed for San Juan. Gaity prevailed. Toasts were drunk. Envious landlubbers came down to say goodbye to their more fortunate friends heading for the tropics. When we sailed about 3 or 4 o’clock everybody seemed happy, carefree. And so it went through the dinner hour and afterward until everyone had bedded down. Sometime after midnight we reached the open Atlantic and the early smooth sailing became a thing of the past. That ocean can be rough and dangerously rugged in the winter.

Charlie Dressen was my cabin mate. During the night his steamer trunk banged from one side of the cabin to the other, narrowly missing Charlie’s head one time as he tried to sleep in his bunk. Shortly after dawn we decided to dress since we couldn’t sleep any longer with the ship pitching, tossing and rolling. We headed on deck and for the dining room and the sitting rooms. Except for the stewards and crew, the whole ship seemed deserted.

Almost everyone was seasick. I was one of the fortunate ones. Lanky George Kelly reportedly got as far as the dining room, smelled bacon and eggs at the door, made a beeline back to his cabin and wasn’t seen again for days.

And the rough weather knocked out Whitey Wistert, a former All-American football player who was trying to make the grade as a right-handed pitcher, as well as most of the other players and the other passengers.

At one point during the day I returned to our cabin and found Dressen in his bunk, fully dressed.

“What’s the matter, Charlie, are you seasick?”

“No, no, Gene, I’m just resting,” he replied. He knew that I knew he was lying.

Jack Ryder doubted the ship captain’s assertion that the storm was due to rough weather around Cape Hatteras, long known as the graveyard of ships.

“We’ve been passing Cape Hatteras for three days,” said Jack later. “And at the point of the cape it’s just six inches wide. Time for another scotch and soda.”

The Atlantic calmed down gradually as we neared Puerto Rico. On the fourth or fifth day Kelly, Sheehan, Wistert and other players and passengers we hadn’t laid eyes on since the day we sailed from New York put in their appearances on the deck.

I’ll never forget Kelly on that last day just before we docked, pale and wan, sitting in a deck chair all bundled up in a blanket up to his chin, evidently ready to swear off ship travel forever.

By this time it was warm, with tropical sunshine, blue seas and palm trees coming into view as we neared the old Morro Castle and our dock in San Juan. Numerous Puerto Rican officials and baseball fans greeted us. By noon we had checked into the old Condado Hotel and soon were taking refreshments in the colorful Garden-By-The-Sea, with salt air on our lips. I knew this was going to be a most enjoyable spring training for me.

My duties were light. All I had to do was to make a note of when players checked into the hotel to see that the bills were straight. During workouts I took pictures to send back to the Cincinnati papers. And I wrote feature articles. Cabled stories were out of the question because of the heavy expense, so I air-mailed my pieces to papers in Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia and southwest Indiana. Pan American had flights out of San Juan only two or three times a week, so I didn’t have to hurry to write my stories.

The rest of the players dribbled in from all over until we had about 35 veterans and rookies on hand. Charlie ordered calesthenics to start workouts, followed by batting and infield practice, fielding bunts, pitchers covering first base, wind sprints and all the rest. Starting by 9:30 or 10 AM, we were finished by 1 o’clock. A light lunch, a siesta and then many of us were swimming in the hotel salt water pool. We were told not to use the beach because the Atlantic was full of barracudas, which could slash even a wader to ribbons.

That Garden-By-The-Sea was most attractive. We ate there, and many of us danced there under the stars night after night. Tvvo orchestras took turns, providing a blend of American and Latin music. The intoxicating setting could hardly have been more romantic. In my job I felt it my duty to provide the newspaper men with drinks and put it all on the expense account. And there were other attractions, including alluring Puerto Ricans and vacationing girls from the mainland.

That combination of salt air, moonlight in the tropics and Latin music often kept me busy till 2 or 3 AM. Next morning by dawn I was wide awake, refreshed, not wanting to miss anything. The players, however, usually had been tired enough to disappear into their rooms by 10 o’clock or so.

While MacPhail was still back in Cincinnati I had occasion to cable the home office, despite the stiff rates. One of our players came up with what might be called a “social disease.” Dressen came to me with the news.

“You know what MacPhail told us in New York,” I said. “We have to let him know immediately.”

So I got out my cable code book, which was designed to let me say a lot injust a few words. The cable to MacPhail read something like this: ALAMY ANFIB ANHOC DEZIT QUANVI LARRUSCU. Translated, it told the story about the rookie player “Larruscu” and what ailed him. (I have purposely substituted the name “Larruscu” for the player’s real name.)

When the coded cable reached MacPhail’s office, Larry was too impatient to get out his own code book. Instead, he yelled at Frances Levy, his secretary and a proper middle-aged spinster, to decipher it. “What in hell is Karst trying to tell me?”

Miss Levy got out the code book and, blushing, read him the translation into plain English. MacPhail exploded, then dictated his reply in clear, uncoded English:

“PUT LARRUSCU ON THE SLOWEST AND WORST CARGO SHIP YOU CAN FIND AND SEND HIM HOME SUSPENDED WITHOUT PAY. MacPhail.”

I got busy on the project and lined up the player’s passage home on a slow freighter. I fear the accommodations were not nearly as bad as MacPhail wanted for the sinner. He did recover to play in the Cincinnati minor league organization, but he never reached the majors.

Our pleasant routine continued into early March. MacPhail had come to San Juan not too long after Larruscu left. He rounded up Dressen and me and said we were going downtown to the office of the telephone company. There we found the Governor of Puerto Rico, phone company officials and other guests. The occasion was the initiation of the first telephone service between San Juan and the mainland.

Champagne was served while we waited for the official first conversation. We sat around tables with earphones on so we could listen in. It was the voice of Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes coming from Washington with the Governor in San Juan. When their greetings were ended, we were told that a commercial call was scheduled with Powel Crosley Jr., owner of the Reds, in Cincinnati. Crosley and MacPhail discussed the weather in Cincinnati contrasted with the warm sunshine of San Juan, how the spring training was progressing, and what the prospects were for a good baseball season in 1936. When MacPhail ran out of things to talk about he said to Crosley, “Here’s Charlie Dressen.” Dressen talked to Crosley a minute or two and then he ran out of things to talk about.

I happened to be sitting next to Dressen, and without any warning Charlie thrust the phone into my hands, saying, “Mr. Crosley, here’s Gene Karst.” This caught me completely by surprise and soon I, too, was tongue-tied and the conversation ended with our goodbyes. I confess that the celebratory champagne may have slurred my enunciation. I was embarrassed when I later learned that our stilted conversations with Crosley had been broadcast simultaneously over his Cincinnati radio station, WSAI.

The Reds played several exhibition games against Puerto Rican all-stars. Then McPhail dispatched me by ship to Ciudad Trujillo to line up games for the half of the team that wouldn’t be remaining in San Juan.

Those of us tapped for the trip left San Juan reluctantly. A large group of local fans and friends came down to the SS Coamo to see us off. As the sun set we sailed into the Atlantic, past that landmark the Morro Castle and eventually through Mona Pass, southward and westward into the Caribbean. When dawn came we saw the mountains of the Dominican Republic on our right. When the Coamo docked at 10 AM, we were welcomed by a large crowd of Dominican baseball fans, as well as officials of the Trujillo government and William Ellis Pulliam, who was in charge of the Customs Service of the country. Pulliam was an official of the United States Government, sent there to collect export and import duties the U.S. thought the Dominicans owed us. Pulliam was the brother of the late Harry Pulliam, who had been president of the National League some years previously.

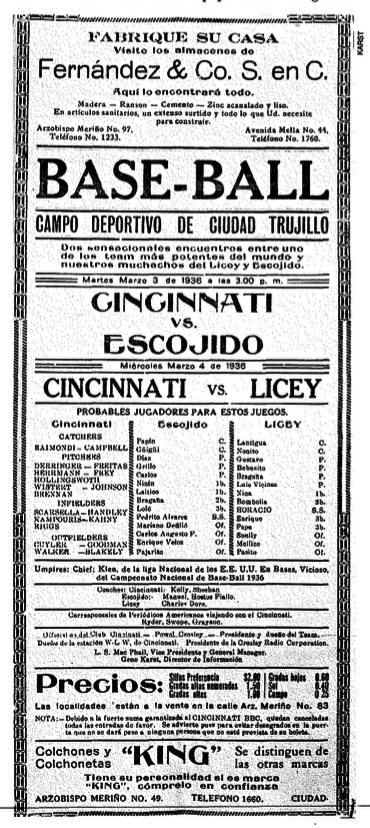

During my first trip to the Dominican Republic, I had seen Hector Trujillo, brother of the dictator, about arrangements for the two exhibition games. With his brother’s approval, half-holidays were decreed for both of the days the Reds were in town.

H.F. Arthur Schoenfeld, American Minister to the country, threw out the first ball for the first game. The Reds won both games, though the second one wasn’t decided until the ninth inning, when Kiki Cuyler doubled with two men on base, giving us a 4-2 victory.

It seemed fitting that the oldest professional team in baseball, the Cincinnati Reds, should carry the banner of major league baseball into the oldest city in the New World.

The oldest city, however, carried the newest name anywhere. A short time previously the brutal dictator had changed the ancient name of Santo Domingo to Ciudad Trujillo in honor of himself!

At our hotel I got into conversation with a chambermaid. She told me about herself and her family, saying she had a 6-year-old son. I asked what grade the boy was in.

“He doesn’t go to school,” she said.

I asked why not.

“He doesn’t have any shoes. And it’s forbidden to go to school without shoes.”

Visiting American tourists generally had remarked about how clean the city was, how well everybody was dressed. But it was just part of the dictator’s plan to make a fine impression on visiting foreigners. Behind this facade of a happy, prosperous, well-run country, the Trujillo dictatorship was one of the most brutal regimes any country ever saw. The real poverty of the people was carefully hidden.

We did not realize this at the time. Instead, we visited the tomb of Christopher Columbus at the old cathedral and did other sightseeing. The country was noted for its mahogany, so many of the players picked up small wooden souvenirs such as canes, cigarettes, and jewel boxes, book ends, and ashtrays. However, they had to keep in mind the need to limit their luggage to 44 pounds for the upcoming flight on the clipper ship.

In retrospect, I now realize that I was in distinguished company that whole spring training trip in 1936. Dressen, our manager, was destined to lead the Brooklyn Dodgers to pennants in 1952 and 1953, and he later managed the Milwaukee Braves, the Washington Senators, and the Detroit Tigers.

Kelly, one of our coaches, had been a great first baseman for John McGraw‘s New York Giant pennant winners in the early 1920s and was eventually elected to the Hall of Fame. Sheehan, the other coach, had pitched for various clubs and later managed the San Francisco Giants. Hazen “Kiki” Cuyler had been a stellar outfielder with the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Chicago Cubs before joining the Reds. He, too, was elected to the Hall of Fame. So was one of baseball’s most colorful personalities and most competent umpires ever, Bill Klem.

Nor should we forget the guy who dreamed up the whole, history-making training jaunt: Larry MacPhail. Think of any adjective, complimentary or derogatory, and you could apply it to him. He had pioneered night baseball in the major leagues the year before. An avid devotee of plane travel, he flew the Reds from the West Indies to the United States long before any other team took to the air. (He claimed to have been a passenger on the second commercial plane trip in history, back in 1915 or 1916, between Tampa and St. Petersburg.) In the future he was to gain fame as boss of the Brooklyn Dodgers and later head man of the New York Yankees. He, too, finally was elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame, taking his place in Cooperstown in 1978.

MacPhail’s tour of duty in Cincinnati was brief. But he took a tail-end ball club and set it on its way to success. When he left the Reds at the end of 1936, Warren Giles, his successor, inherited such stalwarts as Paul Derringer, Ernie Lombardi, Billy Myers, and IvaI Goodman. Others still in the minor league organization included Johnny Vander Meer, Frank McCormick, and Harry Craft. These were the men who brought Cincinnati National League pennants in 1939 and 1940.

I always loved getting away from midwinter snow and ice to go south to spring training with various baseball clubs, but that 1936 expedition with the Cincinnati Reds was the best ever.

GENE KARST (1906-2004) was the first full-time publicity man for any major league club (the 1931-1934 St. Louis Cardinals). He was later with the Cincinnati Reds, Montreal of the International League, and Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League, then spent 27 years with the State Department, the Voice of America and the United States Information Agency. He is the principal author of “Who’s Who in Professional Baseball.”