Rhéal Cormier

Canadian Rhéal Cormier had two distinct major-league careers. Through most of the 1990s he was a middle-of-the-rotation starter for the St. Louis Cardinals and Montreal Expos. After Tommy John surgery, however, he reinvented himself as a successful late-inning, short stint, relief pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, Philadelphia Phillies, and Cincinnati Reds.

Canadian Rhéal Cormier had two distinct major-league careers. Through most of the 1990s he was a middle-of-the-rotation starter for the St. Louis Cardinals and Montreal Expos. After Tommy John surgery, however, he reinvented himself as a successful late-inning, short stint, relief pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, Philadelphia Phillies, and Cincinnati Reds.

Along the way he became universally recognized as a durable reliever, valued teammate, and all-around good guy. He ended his 16-year career with 683 appearances, second only to Paul Quantrill’s 841 among Canadians. When Cormier died of cancer on March 8, 2021, former teammate Dan Plesac tweeted, “One of my all-time favorite teammates. He made everyone he played with better.”1

Rhéal Paul Cormier was born on April 23, 1967, in Moncton, New Brunswick, one of five children of Ronald and Jeannette Cormier. Rhéal’s father was a truck driver, making his living hauling logs or lobsters or whatever else needed to be shipped to the larger cities in Canada or the United States. His mother worked bagging lobsters in the local Paturel Seafood plant, while also raising the children.2 There was little money to spare. Cormier once explained that he and his brother, Donnie, did not play hockey as kids, as one might expect of boys growing up in Canada, because the equipment was too costly.3 Instead, they both turned to baseball, honing their skills throwing rocks at mailboxes and playing catch in snowbanks. “Summer? I know it wasn’t long. Maybe the middle of June to the first two weeks of August,” Cormier said.4 Cormier saw his first major-league game when his father took him and Donnie along on a trucking run to Boston that included a side trip to Fenway Park to see the Red Sox play.5

Rhéal was discovered by Art Pontarelli, a major-league scout who at the time was the coach at the Community College of Rhode Island (CCRI). Pontarelli moonlighted by running a baseball clinic in Moncton, where he found Rhéal, a self-conscious little lefty (he threw and batted left-handed) who was one of the few French speakers on the Moncton squad. Jeannette Cormier regularly drove her boys the 30 miles from their home in Cap-Pele to Moncton, where they could find better baseball competition. Rhéal was never really comfortable on that Moncton team. “I didn’t think they wanted me there,” he later said.6 Pontarelli eventually coached the Moncton team to a championship in a national tournament for teenagers, with Cormier as the star pitcher. In 1987 he brought Rhéal and brother Ronald down to play at Rhode Island and attend school there. When Cormier could not afford to attend the next year, Pontarelli got him a scholarship at the University of New Haven, but Cormier did not like the New Haven coach’s approach. He returned home and chopped wood until he had saved up enough money to return to Rhode Island.7

With Rhéal back in the fold at CCRI in 1988, and with his brother Donnie playing second base, CCRI went to the Junior College World Series for the first time, finishing third. Also in 1988, Cormier was a member of the Canadian Olympic Baseball Team. Baseball was a demonstration sport in that year’s Games in South Korea. Canada went 1-2 in the tournament but did manage to defeat the United States team.

Coming off his collegiate performance in 1988, Cormier was named as a finalist for the Dick Howser Award, given to the outstanding collegiate player,8 and in June, he was drafted in the sixth round by the St. Louis Cardinals. Brother Donnie was not drafted, much to his disappointment. Rhéal described Donnie as the real baseball fanatic in the family. “Donnie loved the sport more than I did growing up,” he said. “When I was drafted and he wasn’t, it was tough for him to accept at first. I never really wanted to play a major sport. I played volleyball and soccer in high school. I thought coming from where I come from, I don’t really have a chance at anything else.”9 The Cardinals gave him a chance, however, and Cormier made the most of it.

Cormier advanced rapidly through the Cardinals farm system. In 1989 he went 12-7 with a 2.23 ERA with the St. Petersburg Cardinals. With Double-A Arkansas in 1990 his record on a poor team was an equally poor 5-12, 5.04, but he impressed the Cardinal management with his control and strikeout/walk ratio. At the end of the 1990 season he was promoted to the Triple-A Louisville Cardinals, going 1-1, 2.25 in four starts. The performance was good enough to earn him a prospect label and an invitation to spring training.

Cormier pitched well for the Cardinals in spring training, but manager Joe Torre was reluctant to bring him along too quickly, “He’s close,” Torre said of Cormier. “Ideally, you’d like to see [him] get a full year in Triple A.”10 Musing about reaching the majors, Cormier said, “It would be good for French-speaking people. I know when I get to Montreal Stadium,11 people will say, ‘Wow, how come Montreal doesn’t have him?’”12 Cormier did not make the team out of spring training, starting the season back at Louisville, but when starting pitcher Ken Hill went on the disabled list in August, Cormier was recalled.

Besides experience, one thing Cormier picked up in the minor leagues was the nickname Frenchy. He explained to the Boston Globe’s Gordon Edes that his nickname at home was “Chuck, because I was always ‘chucking’ a baseball when I was growing up.”13 The “Frenchy’ moniker was perhaps a natural for the French-speaking Cormier, but in reality his ancestry is Acadian, a small group of French-speaking people who live mostly in the Province of New Brunswick (as well as in the bayou country of Louisiana, where they have become known as Cajuns) and whose culture is different than that of the French Canadians of Quebec.

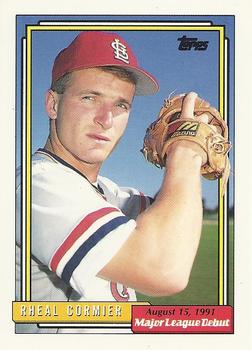

Frenchy made his major-league debut on April 15, 1991, in a start against the New York Mets. He went six innings and picked up the victory in a 4-1 Cardinals win. In so doing, he became the first Cardinals left-handed starter to win a game at Busch Stadium in nearly a year. “It’s a great feeling,” Cormier said after the game. “After I got through the first inning, I told myself, I can pitch here.”14 Manager Torre said, “It was like he’s done this before. I really like his poise.”15 One month later, on September 15, Cormier pitched his first complete game, scattering nine hits and beating the Mets again, 7-2. On September 20 Cormier pitched perhaps his best game of the season, again against the Mets, but lost, 1-0, when the Mets scored an unearned run on an error by, of all people, the great Ozzie Smith. Cormier made 10 starts to finish out the season and went an unspectacular 4-5 with a 4.12 ERA, but the Cardinals felt he had pitched better than the statistics showed.16

Over the winter, rumors flew that Cormier would be traded to Montreal for Andres Galarraga. The deal made sense. The Cardinals wanted Galarraga and Montreal wanted the publicity boost that would come with having a French-speaking Canadian on the roster. Cormier, however, did not want to leave St. Louis or pitch with the pressure of being the “hometown boy.” He was relieved when the Cardinals refused to deal him and sent pitcher Ken Hill to Montreal instead.17 Cardinals general manager Dal Maxvill said, “He pitched well for us and we do like him. We like his make-up. We have since we signed him.”18 The winter was notable for another reason. In January, Cormier married his high-school sweetheart, Lucienne LeBlanc.19

Manager Joe Torre was counting on the 5-foot-10, 185-pound Cormier to be a regular part of the rotation in 1992, but plans were derailed when Cormier came down with the flu and missed the last two weeks of spring training. He began the season in Louisville to build up his pitching strength, but was recalled after just one start when pitcher Bryn Smith went on the Cardinals’ disabled list. His first starting assignment was on April 13, Opening Day in Montreal, in front of dozens of friends and family and an appreciative Montreal crowd who cheered him upon his introduction. Cormier lasted five innings, giving up three runs (one earned) and was the losing pitcher, 3-2. Cormier began the year with five straight losses and did not win his first game until June 14. His second win did not come until July 10, by which time he was 2-7. He finished strong, however, winning seven in a row to end the season with a respectable 10-10 record and a 3.68 ERA.

After winning his first start in 1993, Cormier went winless in his next seven starts and was relegated to the bullpen. This pattern would repeat throughout the season as Cormier mixed in three stints as a starter with two stretches in the bullpen. While he wanted to be a starter, he felt that the time in the bullpen helped him. “I probably am more aggressive than I was before. Coming out of the bullpen … you basically use your fastball and forkball and go right at them.”20 The 1994 season was full of frustration. He started in the rotation but went on the disabled list with shoulder stiffness at the end of April. Cormier returned in May only to go back on the disabled list with a back injury. When he was finally healthy, he made two starts in August and then the season was shut down by the players’ strike.

During spring training of 1995, manager Torre announced he planned to use Cormier out of the bullpen. Cormier still pictured himself as a starter and so he was a little surprised, but pleased, when he learned he was traded (along with outfielder Mark Whiten) to the Boston Red Sox for third baseman Scott Cooper and pitcher Cory Bailey. “I talked to [Boston general manager Dan] Duquette and he told me he tried to get me when he was in Montreal, but couldn’t. … Here [with Boston] I know I have a job in the starting rotation.”21 As it turned out, after three starts for the Bosox, Cormier found himself relegated to the bullpen when Roger Clemens returned from the disabled list. He pitched very well for Boston out of the pen. When pressed back into a starting role in August, Cormier responded with three victories in four starts as Boston went on a 20-2 run that propelled the Red Sox to the American League East Division championship. Cormier was the winning pitcher when the Red Sox clinched the championship on September 20. He made two relief appearances in the Division Series as Boston fell to the Cleveland Indians in three straight games.

On January 10, 1996, Cormier was finally acquired by the Montreal Expos in a deal that sent shortstop Wil Cordero to the Red Sox. Montreal got its wish to reap the publicity bonanza that came with having a Canadian on the roster, and Cormier got his wish to be a starting pitcher. On April 22 he pitched the first and only shutout of his career, a three-hit, 8-0 gem over his old team, the Cardinals. On July 2 he outdueled Atlanta’s Greg Maddux, going 7⅔ innings in a 5-1 victory. Cormier made 27 starts for the Expos until he went on the disabled list in late August. When he returned in September he worked exclusively out of the bullpen. The August injury may have been a harbinger of what was to come. In 1997 Cormier made one start and again went on the disabled list. This time he required Tommy John reconstructive elbow surgery. He would pitch no more that year.

Released by the Expos in the fall of 1997, Cormier was signed by the Cleveland Indians and reported to them for spring training in 1998, but his recovery was slowed by continued arm problems. He eventually made three starts for the Double-A Akron Aeros in May and June, but the arm issues persisted, and he was shut down again. The Indians released Cormier in the fall of 1998, He then signed to return to the Red Sox in January 1999. In spring training, he proved that he was once again healthy and made the team as a relief pitcher..

On April 11, 1999, Cormier celebrated his return to the majors after two injury-filled years by striking out the Tampa Bay Devil Rays’ Dave Martinez, Jose Canseco, and Fred McGriff in order. On April 23 he was ejected from a game for the only time in his career when he plunked Cleveland Indians star Jim Thome with a pitch in retaliation for an Indians pitcher having buzzed a fastball close to Boston right fielder Darren Lewis’s head. The pitch to Lewis had emptied the benches, and Cormier hitting Thome resulted in the second bench-clearing incident of the game. Thome was also tossed for fighting. It seemed an angry exchange, but what the fans did not know was that Cormier and Thome had become hunting buddies during the one spring training Cormier had spent with the Indians. After the game and the on-field confrontation Cormier said, “I was walking out to my car and [Thome] was waiting for a cab. He came over to me and said, ‘No hard feelings, it’s part of the game.’ So, yeah, I gave him a ride to his hotel.”22 The next night Thome and Cormier faced off again. Thome lined out and there were no more fireworks. Thome and Cormier would become teammates in Philadelphia a few years later.

During the 1999 season Cormier appeared in 60 games and worked 63⅓ innings. He was generally used in key situations late in games, often for one inning or less, but he was not strictly a left-handed specialist. Cormier’s forkball made him capable of getting right-handed hitters out as well. Cormier took very well to his new role as a late-inning reliever. Manager Jimy Williams praised his performance, saying, “He has been tremendous. He really has.”23 For the season, left-handers hit just .198 against him and right-handers hit .276. He was also effective in the postseason, making six appearances in the ALDS and ALCS with eight strikeouts and no earned runs.

In 2000 Cormier filled the same short relief role, appearing in 64 games and 68⅓ innings, but his ERA rose to 4.61 as Boston, after leading the AL East as late as June 22, fell to second place with an 85-77 record and failed to qualify for a spot in the postseason playoffs. With his effectiveness falling off, he was not tendered a new contract at the end of the season and elected free agency. The 33-year-old Cormier was quickly signed to an $8.5 million, three-year contract by a Philadelphia Phillies team desperate for bullpen help.

Many baseball officials were critical of the big contract given to Cormier. Teams like the Mets were irritated that the Phillies’ offer forced them to up the ante for pitchers they were trying to sign like John Franco. Phillies general manager Ed Wade said that faced with the poor quality of their bullpen, we “couldn’t afford to just be one of the clubs in the bidding [for quality relievers].”24 The Phillies thought they needed to overpay to get what they needed. It didn’t help that Cormier showed up to spring training unable to pitch because of back spasms. Philadelphia Daily News sportswriter Bill Conlin took to calling Cormier, Rhéal (Deal) Cormier, to voice his displeasure over the apparently outsized contract.25 Cormier’s performance did little to assuage the critics. After a decent first half of the season in 2001, he had a rocky second half ending with a 4.21 ERA in 60 appearances and just 51⅓ innings as the Phillies finished second, two games behind the Atlanta Braves in the National League East Division. The 2002 season was worse. The Phillies fell to third place. Cormier was largely ineffective, getting off to a poor start and, never really recovering, being relegated to a mop-up role in the bullpen. For the season he recorded a 5.25 ERA in 54 games, with a low 74 ERA+.

Going into the last year of his contract in 2003, Cormier was reunited with new Phillies pitching coach Joe Kerrigan, with whom he had enjoyed working in Montreal and Boston. After poor seasons in 2001 and 2002, he said he wouldn’t have been surprised if he had been released during spring training.26 After a poor performance on Opening Day that saw him give up five runs to the Florida Marlins, including a Mike Lowell three-run home run, Cormier became what Kerrigan called “one of the best relievers in baseball.”27 From that Opening Day disaster through mid-May, he was almost unhittable, reeling off 19⅓ scoreless innings on only eight hits. The strong performances continued, and manager Larry Bowa began to rely on him more and more in high-leverage situations. In September, as the Phillies battled for a playoff spot, Kerrigan called Cormier “the secret MVP of our pitching staff.”28 The Phillies fell short of the playoffs, but Cormier had his finest season in the major leagues. He pitched in 65 games with an 8-0 record, a 1.70 ERA and a 235 ERA+.29 Left-handers hit just .119 against him and right-handers only .207. Cormier attributed the reversal of fortune to confidence; the feeling that his coaches once again believed in him.30

In 2004 Cormier appeared in 84 games, second to only Kent Tekulve’s 1987 record of 90 for the most appearances by a Phillies pitcher in one season. While he was unable to repeat his 2003 success, he turned in another good season as a late-inning specialist. Off the field, 2004 was a banner year for the Cormier family as Rhéal and his wife, Lucienne, both became United States citizens. The Cormiers, born in Canada, had lived in the United States for more than a decade and both of their children, Justin and Morgan, were US citizens by birth. Cormier told the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Jim Salisbury, “Everything I have comes from this country. I’m proud of America.”31 The couple learned that they had passed their citizenship test in September and were looking forward to voting in the November 2004 election.32

Cormier also emerged as a leader in the clubhouse. As the team struggled to make progress in the standings, the atmosphere around the team deteriorated. Cormier, while not specifically laying the blame at manager Larry Bowa’s feet, spoke of a “brutal pins and needles” atmosphere in the locker room.33 After the season, Cormier contemplated retirement, but when management cleaned house, firing Bowa with two games left in the season34 and releasing pitching coach Kerrigan and third-base coach John Vukovich once the season ended,35 Cormier decided to return. Battling nagging injuries, however, he had a poor season in 2005 as his ERA ballooned to 5.89 and his ERA+ plunged to a dismal 75. Beset by both injuries and ineffectiveness, he appeared in only 14 games in the last two months of the season.

Cormier bounced back in a big way in 2006, regaining his 2003 form. With the shoulder and hip injuries that plagued him in 2005 behind him, he was once again one of the Phillies’ most reliable relievers, working in 43 games and compiling a 1.59 ERA. But with the Phillies out of the playoff picture in July, he was dealt to the Cincinnati Reds in a trade-deadline deal for pitcher Justin Germano. The Reds hoped Cormier would help them make a playoff run. Both he and the Reds fell short of expectations, however. The Reds finished third, out of the playoffs, and Cormier was not able to replicate his successful work with the Phillies.

Returning to the Reds in 2007, Cormier worked in six games. In the first five, he was credited with three holds, but a poor outing on April 18, when he allowed three runs in 1⅓ innings, proved to be his last big-league appearance. He was released on May 7. He signed a minor-league contract with the Atlanta Braves on May 14 and pitched well for the Braves Triple-A team in Richmond, but when he was not promoted to the big-league club, he decided to retire.

Cormier’s 16-year major-league dossier was complete, showing a won-lost record of 71-64 with two saves and an ERA of 4.03 in 683 games.

But Cormier was not finished with baseball just yet. In 2008, at the age of 41, he joined the 2008 Canadian Olympic Baseball Team, 20 years after he had first pitched for the Olympic team. He was the oldest baseball player at the Olympics. He hoped a strong performance might attract major-league interest again. He said, “I am going to try and play as long as I can.”36 The Canadians finished 2-5 in the tournament and Cormier received no calls from major-league teams. His baseball career was over.

In retirement Cormier settled into a mountain home he had purchased in Park City, Utah. His family reportedly enjoyed the snow and the skiing.37 In 2012 he was named to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. He said, “This is an unbelievable honor to have been chosen and mentioned in the same breath as the great Canadians who have been inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame before me.”38 He was inducted in the same class as former Montreal Expo great Rusty Staub. In 2014 he threw out the first pitch at a game in Philadelphia’s Citizens Bank Park to recognize the 10th anniversary of the opening of the ballpark. Cormier was a part of that history. He was the winning pitcher in both the last Phillies win at old Veterans Stadium in September 2003 and the first Phillies win in the new ballpark in April 2004.

Rhéal Cormier died in his native Cap-Pele, New Brunswick, on March 8, 2021, at age 53. In typical Cormier fashion, he had kept his pancreatic cancer diagnosis quiet, and the announcement of his death came as a shock. The Phillies released a statement by his friend, former teammate, and one-time rival, Jim Thome: “Rhéal was one of the most vibrant people I’ve had the pleasure of knowing. He loved baseball, but he always put his family first. Frenchy was the kind of guy who would do anything for you, and I am lucky to have called him my friend for many years.”39

Philadelphia sportswriter Jim Salisbury wrote that while Cormier might have had his ups and downs as a relief pitcher, “[t]here was one area where Cormier was always consistent. He was good people. Always there when the Phillies needed him for a hospital visit or to do something in the community and with a generous end-of-season check made out to Phillies Charities, Inc.”40

Scott Crawford, the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame’s director of operations said, “Not only was he one of the greatest major-league baseball relief pitchers to come out of Canada, but he was a wonderful and charismatic guy who was proud of his Canadian roots and loved his family deeply.”41

Cormier was survived by his wife, Lucienne; his son, Justin; and his daughter, Morgan, as well as a sister, Linda, and three brothers, Reginald, Donald, and Ola.

Last revised: July 4, 2021 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Donna Halper and Len Levin and was fact-checked by Mark Sternman.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author referenced www.retrosheet.com and www.baseballreference.com.

Notes

1 Dan Plesac, Twitter @Plesac19.

2 Gordon Edes, “The Rhéal Deal,” Boston Globe, April 2, 2000: F4

3 “The Rhéal Deal.”

4 “The Rhéal Deal.”

5 “The Rhéal Deal.”

6 “The Rhéal Deal.”

7 “The Rhéal Deal.”

8 Stan Isle, “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, February 29, 1989: 35.

9 Mike Eisenbath, “Rhéal Prospect: Canadian Puts Accent on Pitching,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 27, 1991: 6.

10 Rick Hummel, “Cormier’s Debut a Pitch for His Native Canada,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch,” March 16, 1991: 5C.

11 Cormier was referring to Olympic Stadium in Montreal.

12 “Cormier’s Debut a Pitch for His Native Canada.”

13 “The Rhéal Deal.”

14 Dan O’Neill, “Cards Use a Left to KO Mets,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 15, 1991: 1D.

15 “Cards Use a Left to KO Mets.”

16 Dan O’Neill, “No Home Boy,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 1, 1992: 24.

17 “No Home Boy.”

18 “No Home Boy.”

19 “No Home Boy.”

20 Dan O’Neill, “Aggressive Attitude Helps Cormier Earn Start,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 12, 1993: 30.

21 Nick Cafardo, “Sox Deal Themselves In,” Boston Globe, April 9, 1995: 61.

22 Gordon Edes, “This Time, Sox Bats Have Enough Punch,” Boston Globe, April 25, 1999: D9.

23 Gordon Edes, “This Lefty Has Done All Right,” Boston Globe, August 10, 1999: 77.

24 Bob Bookover, “Phillies Take Limited Hopes to Camp,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 4, 2001: D1.

25 Bill Conlin, “Upon Further Review, It’s Not So Hopeful,” Philadelphia Daily News, March 22, 2001: 107.

26 Jim Salisbury, “Confidence Keys Cormier’s Reversal,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 19, 2003: D1.

27 “Cardinals’ Pujols Sidelined by Flu,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 19, 2003: D5.

28 “Confidence Keys Cormier’s Reversal.”

29 ERA+ takes a player’s ERA and normalizes it across the entire league. It accounts for external factors like ballparks and opponents. It then adjusts, so a score of 100 is league average, and 150 is 50 percent better than the league average. Cormier’s performance in this season was 135 percent above average.

30 “Confidence Keys Cormier’s Reversal.”

31 Jim Salisbury, “Cormier Waits for Call to Citizenship,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 24, 2004: E5.

32 “Cormier Waits for Call to Citizenship.”

33 Jim Salisbury, “Bowa Says He’s Not Worried, but Time Is Running Out,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 29, 2004: E7.

34 Todd Zolecki, “Phillies Manager Ends 4-Year Run,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 3, 2004: D1.

35 Jum Salisbury and Todd Zolecki, “Vukovich Is Offered Front Office Position,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 6, 2004: D4.

36 Bob Duff, “Donning Maple Leaf makes Cormier Feel Like a Kid Again,” Edmonton Journal, August 12, 2008: 29.

37 Jim Salisbury, “Remembering Rhéal Cormier, a Phillie Who Was, Quite Simply, Good People,” Yahoo! Sports March 8, 2021. Remembering Rhéal Cormier, a Phillie who was, quite simply, good people (yahoo.com). Accessed May 7, 2021.

38 “Cormier Honored,” Philadelphia Daily News, February 8, 2012: 58.

39 “Longtime MLB Lefty Cormier Dies from Cancer,” New York Daily News, March 9, 2021: 42.

40 Jim Salisbury, “Remembering Rhéal Cormier, a Phillie Who Was, Quite Simply, Good People.”

41 “Former Canadian Major-Leaguer Rhéal Cormier Dies after Battle with Cancer,” Beyond the Dash, Rhéal Cormier | Obituary | Beyond the Dash. Accessed May 8, 2021.

Full Name

Rheal Paul Cormier

Born

April 23, 1967 at Moncton, NB (CAN)

Died

March 8, 2021 at Cap-Pele, NB (CAN)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.