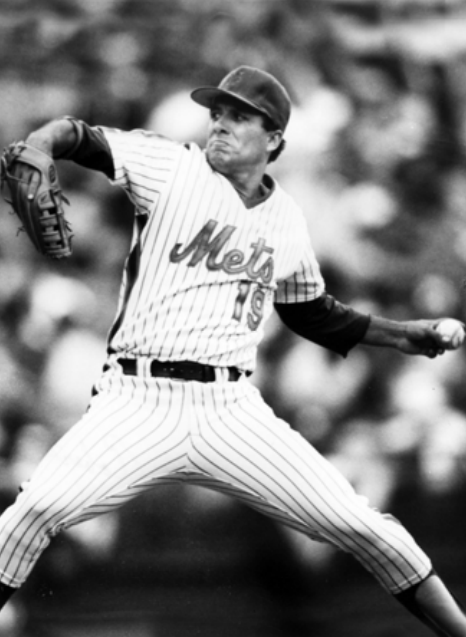

Bob Ojeda

“We didn’t just want to win. We wanted to step on the opponent’s neck,” Mookie Wilson said.1 “What you saw was what you got, like it or hate it,”2 said Bobby Ojeda of the cantankerous New York Mets of 1986. Any championship team is pieced together over time, although it can appear that the success took place overnight. One of the last pieces of the puzzle known as the 1986 Mets was Bobby Ojeda. When the 1985 Mets fell short of a division championship, general manager Frank Cashen went shopping for another left-handed pitcher. He obtained Ojeda and three minor leaguers from the Red Sox for Calvin Schiraldi, Wes Gardner, John Christensen, and La Schelle Tarver.

What did the Mets get out of the deal? The short end of the stick, or so it seemed; Schiraldi and Gardner were two of the brightest pitching prospects in the Mets organization. Ojeda had pitched to a 9-11 record for the Red Sox in 1985, and had done little to distinguish himself in six seasons with Boston. He was brash and opinionated and out of place in the Red Sox clubhouse. “Let’s just say I wasn’t their type,” he said years later. “I didn’t fit the mold.”3 The hope was that Ojeda would win 10 games for the Mets.

With the Mets, Ojeda was in his element and not to be absent from a good prank. Early in the 1986 season, he targeted Kevin Mitchell. After a game in San Diego, Mitchell returned to the clubhouse to find that Ojeda and Ron Darling had cut the sleeves and pants legs off his suit.4

But in the season of his life Ojeda injected a sense of calm around the Mets, going 18-5 with a career-best 2.57 ERA. His team-leading 18 wins were also a career high as were his 148 strikeouts. His .783 won-lost percentage topped the league’s hurlers and he finished fourth in the voting for the Cy Young Award.

At 24 Ojeda was optimistic for his baseball future. “When I’m 47 sitting in my rocking chair, I’ll look back and know I got the most I could have out of myself. I mean the most!” he said in 1981. “So many guys I know are saying now, ‘Man, I should have stayed home more. I should have done my running harder.’ They’re full of should haves and could haves, and now they’re digging ditches. I’ll tell you though, I’d be happy digging that ditch if I knew I had done the best I could.”5

For Bobby Ojeda, the story began in Los Angeles, where he was born on December 17, 1957. His father was a furniture upholsterer and his mother worked for the school system as an interpreter for Mexican migrants.

By 1972, he was 15 years old and pitching for his Babe Ruth League team in Visalia, California. Ojeda was blessed with a live arm and a good fastball but sometimes, like the time he hit five batters in a game, his control was suspect. The scouts did not take notice of him in his days in high school and at the College of the Sequoias in Visalia. He married Tamara Ann Gann in 1977 and became a father in 1978. They had two daughters and a son before the marriage ended in divorce in 1988. In early 1978 Ojeda was working as a landscaper for his brother-in-law, and it looked as though he would not be playing professional baseball. But Larry Flynn, a Red Sox scout who remembered Ojeda from his Babe Ruth days, advised the Red Sox to sign the lefty, who was an undrafted free agent. The Red Sox did so on May 20, 1978.

Ojeda’s first stop was Elmira in the short-season New York-Penn League, where his “blazing” speed took him to a 1-6 record and a 4.81 ERA. But during a postseason instructional league Red Sox pitching coach Johnny Podres taught him how to effectively throw a changeup, and Bobby was on his way.

In 1979 Ojeda went 15-7 with a 2.43 ERA for Class A Winter Haven of the Florida State League, earning a two-level promotion to the Triple-A Pawtucket Red Sox in the International League. He earned his first win at Pawtucket on May 2, 1980, 8-2 over Rochester.

Ojeda’s temper got the better of him in a game on June 27. The umpire banished the batboy for being a bit tardy in replacing his supply of baseballs. The enraged Ojeda, who was not pitching in the game, hurled four baseballs from the dugout in the general direction of the umpire and then dropkicked the ball bag halfway down the third-base line to earn the rest of the night off.6

Ojeda was 4-5 with a 3.39 ERA when, on July 11, he was called up to the Red Sox and put into the starting rotation. He saw his first action on July 13 against Detroit, pitching into the sixth inning. He was taken out in the sixth inning after surrendering a four-run lead. (Boston went on to win the game 8-4.) Manager Don Zimmer was impressed with what he saw. “Of all the guys we’ve brought up here in my seven years, he’s the coolest we’ve had, Zimmer said after the game. “You’d think he’s been here 10 years. He says it’s just a game and all you can do is your best — which is the truth.”7

Ojeda’s first win came against Texas on August 2. Through six innings he shut out the Rangers on five hits and Bob Stanley came on for the save as the Red Sox won 1-0. His record in seven games with the Red Sox in 1980 was 1-1 with an ERA of 6.92. In his last start, on August 11 in Detroit, he allowed a walk, a homer, and a single to the first three batters and Zimmer pulled him from the game, saying he “felt he would be maimed.”8 Ojeda was returned to Pawtucket for the balance of the 1980 season. He was 2-2 with a 2.70 ERA during his late-season stint at Pawtucket, bringing his International League record for 1980 to 6-7 with a 3.22 ERA.

Ojeda worked hard over the winter, using a Nautilus program, and began the 1981 season throwing flames for Pawtucket. “In the big leagues, you have to do the job right away,” he said early in the season. “That adjustment had to be speeded up (for me). Either you do it or you don’t. I didn’t.” He impressed Pawtucket manager Joe Morgan, who said, “When he was up there (in Boston), he found that he couldn’t be a one-pitch (in Ojeda’s case the changeup) pitcher. When some guys learn that, they’re finished. But he knew what he had to do and did it. He worked all winter and has improved. He’s faster than he was last year.”9

In that season, Ojeda was involved — in an unusual way — in one of baseball’s most historic games, the record 33-inning marathon between Pawtucket and Rochester that began on the evening of Saturday, April 18. Ojeda was scheduled to pitch the next game, and watched as night became late night, very late night, and early morning. As the clock passed midnight and the game entered its 20th inning, Ojeda went home and went to bed. Virtually everybody else (including seven Pawtucket pitchers) saw action as the teams played on and on, completing 32 innings before play was suspended on Sunday at 4:07 A.M. with the score 2-2. When the game resumed on June 23, Ojeda took to the mound for Pawtucket to pitch the 33rd inning. He retired Rochester without allowing a run. Pawtucket won the game in the bottom of the inning and Ojeda was the winning pitcher. Asked to sum up his feelings, he said, “I don’t know how to feel.” How does anybody feel who played in a 33-inning game? Nobody knows because it has never happened before. This is terrific. I feel like I am at the Mardi Gras. I was home sleeping by 3:30 A.M. the first time they played. I took a lot of heat from the other pitchers who worked their butts off in that game. I come in, pitch one inning, and get the win. I hope they can take a joke.”10

Ojeda was pitching well, but his stay in the International League was prolonged by the ongoing strike of the major-league players, which began on June 12. Ojeda was called up when play resumed on August 9, by which time his record was 12-9 with an ERA of 2.13. At season’s end he was named the International League’s Pitcher of the Year.

Rejoining the Red Sox, he said, “I’m mentally ready this time. After what happened last summer, you either get shell-shocked or you get tough. I got tough. I built up my upper body on a Nautilus machine and I’ve worked hard on my slider.”11 In his first start after his return, he pitched a complete game victory, downing the Chicago White Sox on seven hits. Former Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk, then with the White Sox, said, “He added at least five feet to his heater.”12 Ojeda was the best pitcher on the Red Sox staff after the strike, posting a 6-2 record with a 3.12 ERA.

His best effort of 1981 came against the Yankees in New York on September 12. After a first-inning walk to Lou Piniella, Ojeda retired the next 22 batters and took a no-hitter into the bottom of the ninth inning, when Rick Cerone of the Yankees doubled and scored on a double by Dave Winfield that cut the Red Sox lead to 2-1. Leaving the game to a standing ovation, Ojeda was relieved by Mark Clear, who saved the win for him.

As the season neared a close, Ojeda was having headaches and feeling tired. He was found to have a blood ailment similar to mononucleosis. He did not pitch after September 27, although the Red Sox were still in contention for the second-half championship. They wound up finishing 1½ games behind the Milwaukee Brewers. Ojeda finished with a 6-2 record for the Red Sox and finished third in the balloting for Rookie of the Year.

Ojeda started 1982 with the Red Sox and, in an injury-plagued season, went 4-6 with an ERA of 5.63. In three of his starts he was unable to get past the first inning. His first win of the season came on April 20 after two losses. He was knocked out, literally, in the first inning of a game against Kansas City on May 16 when he was hit on the shin by a line drive off the bat of John Wathan. His woes were compounded when he pulled his left hamstring muscle on June 11, and after returning to action two weeks later he was sent to the bullpen. His work out of the pen earned praise from manager Ralph Houk, and he was returned to the rotation. But on August 18 he took a fall in the bathtub in his hotel room in Anaheim and injured his shoulder. He did not pitch again in 1982.

Throughout the season Ojeda maintained his confidence and sense of humor. In late June, he said, “There have been moments I have been real, real down. But they don’t last for more than four or five weeks. No, just a few minutes. But twice, it probably just hit me. I mean, everything’s hurting me. But that goes away pretty quick. I mean, I don’t like it. I’m not happy with it. But I’m not a me-guy. As long as the team is winning, it’s not tough.” 13

After the season Ojeda pitched in Puerto Rico and came to spring training in 1983 poised to win back his job in the rotation. He was the team’s fifth starter, which meant that he would not see much action early on. He didn’t get his first win until May 15, defeating Milwaukee 6-1. In his next start, on May 21, he got his first complete-game win in a long time when the Red Sox defeated Minnesota 11-4.

But Ojeda was erratic in his performances, and on one occasion manager Houk paid an unexpected visit to the mound and urged him, not so subtly, to throw strikes. As August came to a close, Ojeda’s record was a disappointing 6-7. But Ojeda had become a different pitcher, showing the aggressiveness he had late in the 1981 season. He won seven of his last eight starts and never allowed more than two runs in a game. He brought his final record to 12-7. His 1.83 ERA in his last eight starts fell from 5.18 on August 17 to 4.04 at the end of the season.

In 1984 Ojeda pitched 216⅔ innings and went 12-12 with a 3.99 ERA. The Red Sox finished fourth in the AL East. His first win of the season, on April 23 in a rain-shortened 2-0 shutout of the California Angels, was his first major-league shutout. He pitched four more shutouts in 1984, and his five blankings were the most by an American League pitcher that season.

But inconsistency, inaccuracy, and injuries stood in the way of Ojeda emerging as a top-flight pitcher in 1984. He had five shutouts and a 9-7 record through July 27. Soreness in his left elbow put him on the disabled list in mid-August and he went 3-5 with a 4.34 ERA over the last two months of the season. In that stretch he walked 27 batters in 66⅓ innings, bringing his walks per nine innings to 3.99, his worst in four years.

In 1985 new manager John McNamara moved Ojeda to the bullpen, not as a punishment, but to groom him as a closer. The experiment was short-lived as the starting pitchers were failing and Ojeda was returned to the rotation. For the season, he went 9-11 with an ERA of 4.00.

Toward the end of his time in Boston, player militancy was brewing again. During a players-only team meeting, the Red Sox discussed the merits of a potential strike. Ojeda dispelled any notions that he went along with the prevailing pro-ownership mood when he said, “I don’t care what you say. They (the owners) are going to try and pay us as little as they can. Yes, if you are older, you don’t want to miss a paycheck being out on strike. But I’m young!” Three months later, he was gone, traded to the Mets.14

Ojeda joined a staff headed by Dwight Gooden, Ron Darling, and Sid Fernandez and to the surprise of some, became the pitching staff’s stopper. By early July he had the 10 wins that were expected of him for the entire season. Win number 10 was especially important. The Mets had lost three games in a row, and although their division lead was at 10½ games, a win was needed. Ojeda held the Atlanta Braves in check, scattering seven hits as the Mets won 5-1. He was 10-2 at that point. His record included two shutouts and five complete games. His ERA stood at 2.24.

By July 18 the Mets were well in command of the NL East and had a 12-game lead. After a loss at Houston that night, Ojeda and teammates Ron Darling, Tim Teufel, and Rick Aguilera went to a place called Cooters Executive Games and Burgers to celebrate Teufel’s becoming a father for the first time.15 As they left Cooters, there was a scuffle between the players and local policemen who were providing security for Cooters. The four players were arrested. As Mets coach Bud Harrelson summed things up, “Things got a little rambunctious and four of our upstanding examples of athletic prowess ended up spending the night in one of that fair city’s finest holding establishments.”16 In January 1987, misdemeanor charges against Ojeda were dismissed.17

Toward the end of the 1986 season, Ojeda began to experience stiffness in his left shoulder. But on September 23 he pitched six innings against the Cardinals and got his 17th win. “It felt good and it took a load off my mind,” said Ojeda after the 9-1 win in which he allowed only three hits. He added, however, that “until you do it again, there’s always a worry.”18

In the playoffs Ojeda cemented his role as stopper. In Game One against Houston, the Astros’ Mike Scott had been dominant, defeating Dwight Gooden 1-0. Ojeda pitched the second game, against 39-year-old fireballer Nolan Ryan. The Mets were not intimidated by Ryan and staked Ojeda to a 5-0 lead. The lefty went the distance, scattering 10 hits as the Mets won 5-1 to even the NLCS at a game apiece. The game was the essential Ojeda.

The Mets advanced to the World Series, only to lose the first two games at Shea Stadium to Ojeda’s former team, the Red Sox. Game Three was at Fenway Park and Ojeda was handed the ball. He went up against another outspoken player, Boston’s Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd. Did the game have any extra meaning to Ojeda? Of course it did, although he said it was “just another game. That’s how I’m approaching it. Nothing personal.”19 Ojeda rose to the occasion, allowing only five hits in seven innings as the Mets won 7-1. As Roger Angell noted, Ojeda “nibbled the corners authoritatively.”20 “That game was the most proud I’d ever been on a baseball field,” Ojeda said later. “Because I didn’t like the Red Sox. I had new friends, real friends. I had teammates who would fight and bleed for me. To do something important for my guys was awesome.”21 He would, in subsequent years, state that it was his greatest triumph on the baseball diamond.22 Ojeda’s win was the first by a left-handed pitcher in a postseason game at Fenway Park since 1918.23

After Ojeda’s win, the teams split the next two games, and the Red Sox were on the verge of winning the World Series. Nevertheless, at least one observer felt that the Series was lacking something in the way of excitement.

Indeed, a San Francisco Chronicle reporter, Bruce Jenkins, was suffering from an extreme case of boredom after the first five games.

“In terms of aesthetics, the World Series has been a stimulating experience this year,” Jenkins wrote “The Eastern fall weather has been magnificent, the cities are first-rate, and there’s the usual charge one gets from walking into Fenway Park or Shea Stadium on a high-stakes evening.

“There’s been only one problem: the games. This is shaping up as the most lifeless, uneventful World Series in 81 years.

“Where’s the drama? Where are the comebacks? Where are the clutch hits in the late innings? Until further notice, the Series’ official theme song is ‘Everything’s Coming Up Teufel.’

“Maybe things will change tonight, when Roger Clemens faces Bob Ojeda in Game 6 at Shea Stadium … with the proud and arrogant Mets one game from elimination.”24

Well?!

It was a must-win for the Mets. Ojeda gave up two runs and five hits in the first two innings. By the time he left the game after six innings, the Mets had tied the score, 2-2. Ojeda’s work was done and it would be up to his teammates to keep the dream alive — they did. Two days later, the Mets had their second World Series championship.

What was the essence of Ojeda’s success in 1986? He told Roger Angell: “A run is a run and you try to prevent those. There’s so much strategy that goes into that. Each day is different. Each day you’re a different pitcher. Consistency is the thing, even if it’s one of those scuffle days. When I’ve started, I’ve been very consistent, and that’s something I’m proud of. I led the league in quality starts last year — you know, pitching into the seventh inning while giving up three runs or less. That means something to me.”25

Coming off his 18-5 performance in 1986, great things were expected of Ojeda in 1987 but it became a season of frustration. Ojeda’s first start was on Opening Day, when he took on the assignment after Dwight Gooden was placed on the disabled list after testing positive for cocaine. Ojeda was up to the task, allowing one run in his seven innings of work as the Mets defeated the Pirates 3-2. Not only was it his first win of the season, it was also to be his best outing of the season — by far.

On April 21 Ojeda began to experience pain in his left elbow. He missed 10 days, and upon returning lost two games. In a game against Atlanta on May 9, he left after one inning, was charged with the loss, and his record stood at 2-4. Surgery to reposition the ulnar nerve in Ojeda’s elbow was performed on May 23, and it was expected that he would miss the balance of the season. But he was able to return to action earlier than expected. As August turned into September and the Mets were still in the chase, Ojeda returned. On September 8 he pitched two scoreless innings in relief as the Mets defeated the Phillies to remain within 2½ games of the division lead.

Time was running out on the Mets when on September 20, in a slugfest with the Pirates, Ojeda entered the game in the 10th inning with the score 7-7. His first two innings were virtually flawless — no runs, no hits, one walk. The Mets scored a run in the top of the 12th, but the Pirates got one in their half of the inning. In the bottom of the 14th inning, Barry Bonds tripled and scored on a sacrifice fly to end the 4:59 marathon. Ojeda was tagged with the loss, but deserved a better fate — and the Mets were still 2½ games behind. They finished three games behind the Cardinals.

In 1988, after elbow surgery, Ojeda went 10-13, but was more effective than the record would indicate. His ERA was 2.88, he equaled his career high in shutouts, and his strikeout-to-walk ratio was a league-leading 4.03. In 10 of his losses, the Mets scored two runs or less. But the most telling blow of all came when Ojeda was not pitching. On September 21, as the Mets were poised to win their second division championship in three years, he partially severed part of his left middle finger while using clippers to do some hedge trimming. Surgery by Dr. Richard Eaton to repair the finger was successful and Ojeda was able to look forward to 1989.

While recuperating from the surgery, Ojeda became involved with the Tole Indian reservation near his hometown of Visalia, California. He sought to raise funds to build a home for displaced children on the reservation. He also married for the second time in 1988. He and his wife, Ellen, have two children.

Not only did Ojeda return in 1989, but he had one of his better seasons, finishing with a 13-11 record and a 3.47 ERA. He lost his first start of the season to the Cardinals, 3-1, but pitched into the seventh inning, scattering six hits and allowing only two earned runs. He received a standing ovation when he left the game. After the game, Ojeda said, “In my dreams, I pitched to a different scenario. I wish we had won, but I’m very grateful to be here. Spring training is great, but this is the real McCoy.”26 Although feeling no pain, Ojeda was unsuccessful in his first four starts. On May 2 he unleashed his fastball to complement his ever-present “dead fish” changeup and defeated the Braves 7-1. He spun a three-hit 1-0 shutout against the Phillies on June 17 for the Mets’ first complete-game shutout of the season, but his record stood at a disappointing 5-9 on July 16. His ERA had ballooned to 4.19. And then Ojeda turned his season around, going 8-2 in his last 13 starts with an ERA of 2.60. But in his final appearance of the season, he lost 2-1 to the Phillies in a game that eliminated the Mets from the race for the division championship. The Mets finished in second place, six games behind the Chicago Cubs.

In 1990, after acquiring Frank Viola, the Mets had an abundance of starting pitchers and Ojeda did not have a regular turn in the rotation. Before May 22 he had started only one game and was 0-2. He was inserted into the rotation on that day and responded with his first win of the season, 8-3 over the Los Angeles Dodgers. But the team, despite the wealth of pitching, got off to a poor start, and on May 27 were 20-22 and in fourth place. Manager Davey Johnson was replaced by Bud Harrelson and Ojeda remained in the starting rotation. In June he went 3-0 in five starts and the Mets moved into a one-day tie for first place. However, inconsistency set in during July, and Ojeda spent most of the balance of the season back in the bullpen. For the season, he appeared in 38 games, starting 12. His record was 7-6 with an ERA of 3.66 as the Mets finished second to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

At the end of the season, Ojeda was traded to the Dodgers along with pitcher Greg Hansell for infielder Hubie Brooks, a one-time Met. In his two years with the Dodgers he was used exclusively as a starter. In 1991 he went 12-9 with a 3.18 ERA. In 1991 he was reunited with two teammates from the 1986 Mets, Darryl Strawberry and Gary Carter. On May 31, it was just like the good old days as the Dodgers defeated Cincinnati 7-4. Strawberry doubled and homered, Carter doubled and threw out two baserunners, and Ojeda pitched the first six innings to get his fourth win of the season — and the Dodgers were in first place! The Dodgers were in the race the entire season, finishing second to the Braves by one game.

In his second year with the Dodgers, Ojeda was less successful. He went 6-9 with a 3.63 ERA. There were flashes of brilliance like his 6-0 shutout of Cincinnati on April 20, but for the season he had only two complete games. The Dodgers went 63-99 and finished in last place in their division. After the season, Ojeda became a free agent and signed with the Cleveland Indians.

Ojeda was in spring training with the Cleveland Indians when tragedy struck on March 22, 1993. A fishing and boating enthusiast, he went fishing on a scheduled day off from practice with teammates Tim Crews and Steve Olin. As they returned in the early evening darkness, their boat crashed into the dock. Crews and Olin were killed and Ojeda was badly injured. He suffered severe head lacerations and lost nearly four pints of blood. He went away for a bit after getting out of the hospital to grieve and decide what he wanted to do. He did return to the playing field, first with Cleveland at the end of the 1993 season and then as a free-agent pickup with the Yankees, who released him early in the 1994 season. In his 15-year career, Ojeda had a 115-98 record with an ERA of 3.65.

After the Yankees, Ojeda’s life took a different path. He stayed away from baseball until 2001, when he became the pitching coach for the Mets’ Brooklyn affiliate in the Class-A New York-Penn League. In 2003 he moved to Double-A Binghamton in 2003 but was unhappy and went back home to New Jersey at the end of the season. In 2009 Ojeda was lured back to baseball, this time as a postgame commentator on the Mets’ Network SNY, a position he held through the 2014 season.

Last revised: October 9, 2022 (zp)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the endnotes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, the Bob Ojeda file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Mookie Wilson with Erik Sherman, Mookie: Life, Baseball, and the ’86 Mets (New York: Berkley Books, 2014), 134.

2 Jeff Pearlman, The Bad Guys Won! (New York: Harper Collins, 2004), 5.

3 Pearlman, 44.

4 Pearlman, 156.

5 Steve Harris, “Ojeda Proves the Scouts Wrong on Potential,” Boston Herald-American, October 6, 1981: 55.

6 The Sporting News, July 19, 1980: 53.

7 Mike Scandura, “Inches as Good as a Mile for Ojeda in Boston Debut,” Pawtucket Evening Times, July 14, 1980.

8 Joe Giuliotti, “Red Sox: Ojeda Arrives,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1981: 55.

9 Steven Krasner, “Stock Rises for Beefier Ojeda,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1981: 46.

10 Steven Krasner, “Curtain Falls on 33 Inning Drama,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1981: 45.

11 Tim Horgan, Boston Herald-American, August 10, 1981: B-1.

12 Joe Giuliotti, “Red Sox: Ojeda Arrives,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1981: 55.

13 Steve Harris, “Frustrated Ojeda Maintains a Positive Pitching Attitude,” Boston Herald-American, June 29, 1982: 42.

14 Pearlman, 223.

15 Wilson, 137.

16 Bud Harrelson, Turning Two: My Journey to the Top of the World and Back With the New York Mets (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin’s Press, 2012), 194.

17 Joseph Durso, “Darling, Teufel Get Probation; Charges Dismissed for Two Others, New York Times, January 27, 1987: A-19.

18 The Sporting News, October 6, 1986: 13.

19 Pearlman, 225.

20 Roger Angell, Once More Around the Park: A Baseball Reader (New York: Ballantine Books, 1991), 254.

21 Pearlman, 227.

22 Wilson, 189.

23 Angell, 254.

24 Bruce Jenkins, “The Most Boring Series Ever? — Boston Can End it Tonight,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 25, 1986.

25 Angell, 303.

26 Joseph Durso, “Ojeda’s Comeback Provides Met With a Gain in Defeat,” New York Times, April 6, 1989: D27.

Full Name

Robert Michael Ojeda

Born

December 17, 1957 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.