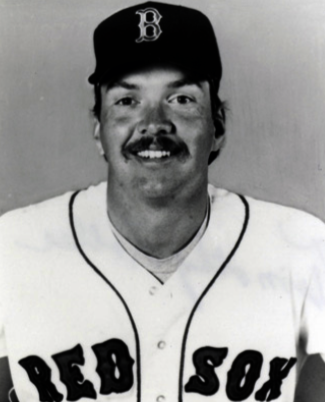

Tim Lollar

After an All-American career as a DH and pitcher at the University of Arkansas, Tim Lollar broke in to the big leagues as a reliever with the New York Yankees in 1980. Traded to the San Diego Padres the following season, Lollar emerged as one of the senior circuit’s most promising starters, winning 16 games in 1982. Battling injuries and struggling with control, Lollar did not achieve his success his breakout season portended, finishing with a 47-52 record in seven big-league seasons, including pennant-winning campaigns with the Padres (1984) and Boston Red Sox (1986).

After an All-American career as a DH and pitcher at the University of Arkansas, Tim Lollar broke in to the big leagues as a reliever with the New York Yankees in 1980. Traded to the San Diego Padres the following season, Lollar emerged as one of the senior circuit’s most promising starters, winning 16 games in 1982. Battling injuries and struggling with control, Lollar did not achieve his success his breakout season portended, finishing with a 47-52 record in seven big-league seasons, including pennant-winning campaigns with the Padres (1984) and Boston Red Sox (1986).

William Timothy Lollar was born on March 17, 1956, in Poplar Bluff, a town of about 15,000 inhabitants located in the southeast corner of Missouri. His parents were Homer Fredrick and Betty Jo (McHenry) Lollar, both native Missourians who married in 1948. Despite claims otherwise, Tim is not related to longtime Chicago White Sox catcher Sherm Lollar. When Tim completed second grade, his family relocated to Farmington, a mining town situated in the Ozarks, almost equidistant between Poplar Bluff and St. Louis. The elder Lollar owned a wholesale meat business. He was tragically killed in a hunting accident when Tim was about 13. His mother worked as a teacher’s aide to provide for him and his sister, Janis. An athletic youngster and unabashed St. Louis Cardinals fan, Tim started playing baseball on local sandlots and youth leagues, graduating to Babe Ruth and then American Legion by the time he was 16. He starred in baseball and football at Farmington High School, but his school did not field a baseball team. Upon graduation in 1974, Lollar accepted an athletic scholarship to attend nearby Mineral Area College.

Lollar’s baseball career seemed to reach its end when he completed his second and final year of junior college in 1976. But like so many players before and since, he had a stroke of luck. Longtime St. Louis Cardinals scout Fred Hawn, based in Fayetteville, Arkansas, had seen the youngster pitch and hit. Upon his recommendation, Norm DeBriyn, head baseball coach at the University of Arkansas, recruited Lollar. “Lollar has a lively arm, and his fastball has good velocity,” said DeBriyn. “He played very little baseball until he was a freshman but has developed rapidly.”1 Lollar majored in forestry, anticipating a career as a game warden, but those plans were put on hold. Over the course of the next two seasons with the Razorbacks, Lollar emerged as a formidable hitter and hurler. Additionally, he showcased his talent in two collegiate summer leagues – the Texas College League (1976) and with the (Fairbanks) Alaska Goldpanners (1977). The Cleveland Indians chose Lollar in the fifth round of the 1977 amateur draft, but the 21-year-old decided to return to Fayetteville for his final season. It was a wise move. He led the Razorbacks with a 7-1 record and sub-2.00 ERA; however, he was even better as a slugger. Serving primarily as designated hitter, but also playing first base, Lollar led the Southwest Conference with a .423 batting average.2 He was named SWC player of the year and a national All-American at DH, becoming the school’s first player to achieve All-American distinction. The New York Yankees chose him in the fourth round of the 1978 amateur draft. The University of Arkansas honored Lollar in 2005 by naming him to their Hall of Honor.

Lollar spent his first two years in the Yankees farm system with West Haven (Double-A Eastern League) not knowing if the club expected him to be a pitcher, first baseman, or designated hitter. At 6-feet-3 and about 195 pounds, Lollar cut an impressive figure on the mound and in the batter’s box. After logging 31 mostly ineffective innings (5.81 ERA), but batting .255 in 1978, Lollar posted a steady 3.18 ERA in 119 innings while hitting just .230 the following season, suggesting that his future was on the mound. “It was obvious to me that he was a pitcher even if he didn’t know it,” said West Haven and future Padre teammate Chris Welsh.3

After participating in his first spring training with the Yankees, as a nonroster invitee in 1980, Lollar was optioned to the Columbus (Ohio) Clippers in the Triple-A International League. With teammates and prospects Dave Righetti and Welsh projected as future starters, Lollar was moved to the bullpen and set the circuit on fire. He surrendered only 13 hits and posted a 1.09 ERA in his first 33 innings, earning a promotion to the Yankees’ 40-man roster and a call-up to New York on June 24. To make room, the club moved aging utilityman Paul Blair into the role of team scout and minor-league instructor. New York’s starting rotation was lefty-heavy (Tommy John, Ron Guidry, Tom Underwood, and swingman Rudy May), but lacked a portside relief specialist to complement hard-throwing Goose Gossage. In his debut, on June 28, Lollar gave up two hits and one run in two innings of relief at Yankee Stadium. Lollar pitched well (3.86 ERA in 25⅔ innings), but was sent back to Columbus in mid-August. He returned on September 13. With the Yankees’ AL East crown already clinched, Lollar was given his first start on the last day of the season. He tossed two-hit ball over six innings to pick up his maiden win in a game that saw New York establish a new home attendance record.

In the 1980-1981 offseason, Lollar played winter ball in Ponce, Puerto Rico, for manager Stan Williams. He reported to spring training in 1981 in strong form, yet did not pitch very much. “I didn’t know what was going on,” said Lollar. “I thought I’d get sent down to the minors.”4 On March 31 Lollar was shipped along with Welsh, center fielder Ruppert Jones, and utilityman Joe Lefebvre to the Padres in exchange for flychaser Jerry Mumphrey and right-hander John Pacella. Lollar struggled with his new team during the strike-shortened season, posting miserable numbers (2-8, 6.10 ERA, and 51walks in 76⅔ innings). The highlight of his season was probably connecting off Cincinnati’s Tom Seaver on April 28 for his first major-league hit, a solo blast in an otherwise forgettable performance yielding seven runs (five earned) in two innings of relief to pick up his first big-league loss.

Lollar went from being called a failure by San Diego beat writer Phil Collier after the 1981 season to being honored as the club’s most improved player during spring training in 1982, posting a 1.87 ERA and walking just five in 24 frames.5 Collier suggested that Lollar’s unexpected turnaround could be traced to a shouting match the southpaw had with manager Vern Benson while playing winter ball with the Barquisimento Cardinales in the Venezuelan winter league.6 No longer trying to shave the corners, Lollar reared back and let his natural stuff take over. “Tim has been one of our nicest surprises in spring training,” said first-year skipper Dick Williams, who had taken over for Frank Howard after the team’s last-place finish in the NL West. “Last year was frustrating,” said Lollar as the ’81 season commenced. “I was mentally prepared to pitch in the major leagues, but physically I wasn’t,” while acknowledging that he didn’t pitch regularly enough to establish consistency.7

Lollar began the 1982 season by reeling off five straight victories, earning praise from GM Jack McKeon as “the best deal I’ve made.”8 On April 29 he tossed a five-hitter to record his first of four career shutouts, and belted a home run to defeat the New York Mets at Jack Murphy Stadium. “He’s much more aggressive with his fastball and slider this year,” said catcher Terry Kennedy. “He’s challenging the hitters, not nibbling and missing. He’s giving them his best stuff.”9 Lollar, 10-2 with a 2.71 ERA at the All-Star break, was the topic of a mini-controversy when Tommy Lasorda, skipper of the NL squad, snubbed him. League President Chub Feeney subsequently issued a public apology. Lollar struggled after the midsummer classic, losing five of six decisions, suffering from both a “dead arm”10 and a circulation problem in his index finger, which physicians diagnosed as Reynaud’s Phenomenon.11 Returning to his first-half form, the 26-year-old Missourian finished with a bang, going 5-2 and posting a stellar 1.98 ERA over his last eight starts of the season to help the Padres jump to a fourth-place finish (81-81) and record just their second non-losing season in their 14-year history. Syndicated columnist Furman Bisher described Lollar as a “throwback to the age of baggy britches and sleeper jumpers” with his exuberant approach to all aspects of the game.12 Lollar finished with career bests in practically every category, including wins (16), starts (34), innings (232⅔), and ERA (3.13); he also batted .247 (21-for -85) , hit three homers and drove in 11 runs. He joined Clay Kirby, Randy Jones, and Gaylord Perry as the only hurlers in Padres history to win at least 15 games in a season.

Looking to capitalize on his success, Lollar refused the Padres’ 1983 salary offer of $200,000 and became the first player in team history to file for arbitration. He was awarded a dramatic increase to $300,000, six times his ’82 salary. Notwithstanding his new financial status, Lollar struggled in spring training after having pitched in excess of 350 innings the previous year in winter ball and the regular season. “My arm was so tired I felt like I was floating the ball to the plate. … Baseball is a series of adjustment,” Lollar said. “You have to make adjustments with your teammates, with the hitters, the umpires, with yourself. I learned a lot about the hitters last year. I learned a lot about myself. A pitching arm has only a certain amount of elasticity and I pitched some games where I didn’t have anything except good location”13 After just three ineffective starts, Lollar was sidelined for three weeks with elbow pain and inflammation in his ulnar nerve. He returned in early May, but failed to find the groove that made him one of the most promising young hurlers in the NL the previous year. He dropped to 7-12 and completed only one of 30 starts, while struggling with his control (85 walks in 175⅔ innings). His ERA (4.61) was the NL’s third worst among qualifiers. When he did pitch well, he seemed to be beset by bad luck and poor run support (the Padres scored two runs or fewer in nine of his losses). Twice he carried no-hitters into the seventh inning, only to lose each game.

If anything, Lollar was confident as the Padres broke camp in 1984 as a dark-horse selection to capture the NL West crown after two consecutive .500 finishes. “I would be really disappointed if we didn’t win the division,” said the lefty.14 The pitching rotation was led by a core of five under-30 hurlers – Lollar, Eric Show, Ed Whitson, Mark Thurmond, and Andy Hawkins, with swingman Dave Dravecky and offseason acquisition Goose Gossage in the bullpen. The Padres got off to a hot start (14-5) and were in sole possession of first place from June 9 to the end of the season. Lollar praised Williams’s tough, no-nonsense approach en route to the skipper’s first postseason berth since he guided the Oakland A’s to their second consecutive World Series title in 1973. “Sometimes a little chewing out doesn’t hurt a player,” said Lollar. “I don’t think I could ask for a better manager.”15 Although Lollar struggled with his control all season, finishing with the second most walks in the NL (105 free passes and 10 wild pitches in 195⅔ innings), he limited the opposition to just 7.7 hits per nine innings. On June 8 he blanked the Cincinnati Reds on four hits, tied his career high with 12 punchouts (the fifth and final time he recorded at least 10 strikeouts in a game), and knocked in two runs. Though not at his best, Lollar recorded the hitherto biggest victory in franchise history when he tossed eight-hit ball over 5⅓ innings, yielding three runs, in the division-clinching 5-3 victory over the San Francisco Giants in San Diego on September 20. Lollar supplied offensive fireworks, too, belting a three-run homer off Mike Krukow.

The Padres lost the first two games to the Chicago Cubs in the NLCS before waging one of the most storied comebacks in championship history by taking the next three games, and stabbing a dagger in the hearts of Cubs fans who had hoped that their team’s first postseason appearance since 1945 might end a World Series championship drought that extended back to 1908. In Game Four, Lollar lasted just 4⅓ innings, and was charged with three runs and four walks. San Diego’s luck and timely hitting did not continue against the Detroit Tigers, overwhelming favorites in the World Series. Crushed in five games, the Padres’ starting pitchers lasted only a combined 10⅓ innings, yielding 25 hits and 17 runs (16 earned) for a 13.94 ERA. Lollar recorded only five outs in Game Three, victimized for four runs on four hits and four walks.

During the 1984 baseball winter meetings, Lollar was involved in a blockbuster trade when the Padres sent him, highly touted shortstop prospect Ozzie Guillen, third baseman Luis Salazar, and minor-league pitcher Bill Long to the Chicago White Sox in exchange for right-hander LaMarr Hoyt and two minor-league throw-ins (Kevin Kristan and Todd Simmons) who never made it to the majors. The trade was widely panned by the Chicago press and fans. A South Side favorite, Hoyt had led the AL in victories in 1982 and 1983, capturing the Cy Young Award in the latter year on the basis of a 24-10 record for the AL West champs; weight problems limited him to 13 wins and an AL-high 18 losses in ’84. Lollar had a good spring for the White Sox (2.10 ERA in 26 innings), drawing praise from skipper Tony La Russa: “He has a real idea how to pitch.”16 However, Lollar’s success did not translate into the regular season. After making it through seven innings just once in 13 starts, Lollar was traded to the Boston Red Sox for reserve outfielder Reid Nichols, who was batting a paltry .188 at the time. “Lollar will add depth to our pitching staff and that is something we badly need,” said GM Lou Gorman optimistically.17 Slotted as the fifth starter, Lollar went 4-5 in his first 10 starts for the Red Sox, but the final one, on September 13, was disastrous (five runs in 1⅔ innings). He was shunted to the bullpen for the rest of the season and finished with a combined 8-10 record and 4.62 ERA in 150 innings, while the Red Sox finished with a disappointing 81-81 record, good for only fifth place in the tough AL East.

While the Red Sox captured the pennant in 1986, their first in 11 years, the season was a long and agonizingly frustrating one for Lollar. He logged only 43 innings over 32 appearances (one start) and posted a team-worst 6.91 ERA. “They didn’t know what my number was toward the end of last year,” said Lollar who pitched only six times after July 30. “It wasn’t fun for me – even winning.”18 Boston sportswriter Larry Whiteside reported that Boston had tried to trade Lollar after the ’85 season, but his high salary (reported at $625,000) drew no takers, while skipper John McNamara had lost confidence in the hurler because of his wildness (34 walks).19 “I am a better starting pitcher than I am a reliever,” said Lollar. “I’m at the point in my career where I need to pitch. It doesn’t do me any good to sit around.”20

After the Red Sox’ unsuccessful attempts at unloading Lollar yet again in the offseason, the club released him during spring training in 1987. He caught on with the Detroit Tigers, and split the season with the Triple-A Toledo Mudhens of the International League and subsequently with the Louisville Redbirds, the St. Louis Cardinals’ affiliate in the American Association. “The game was no longer fun,” said Lollar, who posted a 3-4 record and 5.87 ERA in 76⅔ innings. “It came off to me as more business than game, and as such I just felt like it wasn’t worth it.”21 Just 31 years old, Lollar retired. In parts of seven big-league season he posted a 47-52 record, carved out a 4.27 ERA in 908 innings, and made 131 starts among his 199 appearances. Always a threat with the bat, Lollar also collected 54 hits, good for a .234 average, clouted 8 home runs, and drove in 38 runs.

After his playing days, Lollar and his wife, Robyn (Schaub) Lollar, a former San Diego sportscaster intern whom he married in 1983, moved to Breckenridge, Colorado, on the recommendation of good friend Goose Gossage. He was involved in homebuilding industry, but was unsatisfied. During his active playing days, Lollar had started golfing and began to take the sport more seriously as a member of the local country club. Eventually he attended the San Diego Golf Academy and was hired by Breckenridge Golf Club in 1992. “He’s one of the best athletes that I’ve ever met,” said Gossage. “Nothing Tim does would shock me.”22 In 1996 Lollar was named the head golf professional at the Lakewood (Colorado) Country Club, and held the position as of 2015. In 2010 he was named the Colorado PGA golf professional of the year. “I feel like I had a great career in baseball,” said Lollar in 2009, “But the things I have done after baseball, getting in the golf business, are more rewarding. This was more brain power and effort and attitude, along with personality and sacrifice. Baseball was all of that too. But throwing a baseball was also God-given talent.”23 As of 2015, Lollar resided in Colorado.

Last revised: December 1, 2016

This article originally appeared in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Sources

Tim Lollar player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Ancestry.com.

BaseballLibrary.com.

Baseball-Reference.com.

Retrosheet.com.

SABR.org.

Notes

1 “Porkers Sign Lefty Hurler, Tim Lollar,” Northwest Arkansas Times (Fayetteville, Arkansas), May 23, 1976: 20.

2 Lollar’s college statistics are from UPI: “Razorbacks, Bears Pace All-SWC BB,” Galveston (Texas) Daily News, June 30, 1978: 2-B.

3 Alexander Wolff, “They were playing his song,” Sports Illustrated, May 31, 1982. si.com/vault/1982/05/31/627601/nfl.

4 Suzanne Seixas, “When a Young Pitcher Strikes It Rich,” Money, June 1983: 110.

5 The Sporting News, November 14, 1981: 53; April 17, 1982: 29.

6 The Sporting News, April 17, 1982, 29.

7 Ibid.

8 The Sporting News, June 7, 1982: 7.

9 Wolff.

10 The Sporting News, August 9, 1982: 17.

11 The Sporting News, July 12, 1982: 29.

12 The Sporting News, August 9, 1982: 9.

13 The Sporting News, March 21, 1983: 34.

14 The Sporting News, January 23, 1984: 35.

15 The Sporting News, January 2, 1984: 40.

16 The Sporting News, April 15, 1985: 24.

17 “Red Sox acquire Lollar,” New York Post, July 12, 1986: 95.

18 Larry Whiteside, “For Lollar, It’s Life in Limbo,” Boston Globe, February 25, 1987: 25.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Robert Moreno, “Where are they now? – Tim Lollar,” Friars On Base. friarsonbase.com/2013/02/05/where-are-they-now-tim-lollar/.

22 Tom Kensler, “Lollar Went From Diamonds to Clubs,” Denver Post, June 9, 2009. denverpost.com/headlines/ci_12789838

23 Ibid.

Full Name

William Timothy Lollar

Born

March 17, 1956 at Poplar Bluff, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.