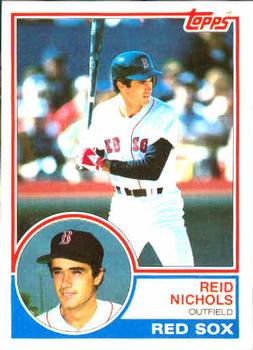

Reid Nichols

Thomas Reid Nichols was drafted in the 12th round of the 1976 draft by the Boston Red Sox. He didn’t know at the time that this was the beginning of a 40-year career in baseball that would take him from the outfield to the front office, and to several cities across North America.

Thomas Reid Nichols was drafted in the 12th round of the 1976 draft by the Boston Red Sox. He didn’t know at the time that this was the beginning of a 40-year career in baseball that would take him from the outfield to the front office, and to several cities across North America.

Nichols was born on August 5, 1958, in Ocala, Florida, to Leon and Judy (Cannon) Nichols. His father worked as an outboard motor mechanic. Reid began playing baseball at age 11 when he was invited to try out for the local Little League team. Despite never having played any organized sports before, he made the team and was named to the league’s all-star team during his first season. The league played games at Grant Field in Dunedin, which in 1976 became the spring-training home of the Toronto Blue Jays.1

Despite growing up around the spring-training homes of several major-league teams, Nichols wasn’t a big fan of the game when he was young. In a June 2020 interview, he said, “The first professional baseball game I attended I was playing in.”2

Nichols continued to excel at baseball at Forest High School in Ocala. Teammate Scott Brantley, who went on to be an NFL linebacker with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, was scouted by major-league baseball teams, who also noticed Nichols. The school’s baseball coach, Mike McGrath, set up a tryout for Nichols and Brantley in Vero Beach, Florida, with the Los Angeles Dodgers. He was also in touch with Red Sox scout George Digby, who later was instrumental in the Red Sox’ drafting Nichols.

Nichols was not paying attention to the draft when he received a phone call to tell him he had been selected by the Red Sox in the 12th round of the June 1976 amateur draft. He had signed a letter of intent to play for the Auburn University baseball team, but decided instead to go pro. He was 17, still a minor, so his contract with the Red Sox was signed by his father.3

His professional career began in the short-season New York-Penn League with the Elmira Pioneers. His teammates included future major leaguers Bruce Hurst, Wade Boggs, Chico Walker, and Glenn Hoffman. The team went 50-20 and finished first in the league. Playing in 23 games, Nichols batted .340.

A right-handed-throwing and -batting outfielder who stood 5-feet-11 and was listed at 165 pounds, Nichols spent the next two seasons with the Winter Haven Red Sox of the Class A Florida State League, batting .264 in 1977 and .247 in 1978. His time there was difficult. “I was 18 years old going up against college guys,” he said.4 In 1979 Nichols was moved up to the high-A Winston-Salem Red Sox of the Carolina League where he had a breakout year. He stole 66 bases in 78 attempts and led the league in runs with 107, hits with 156, total bases with 227, and outfield assists with 23. He hit for a .293 batting average. He had a 30-game hitting streak, which was one shy of the league record, set in 1948.5 He was the runner-up in the voting for the Carolina League MVP, finishing second to Bob Dernier of Peninsula.

Nichols’ performance in Winston-Salem earned him an invitation to the Red Sox’ 1980 spring-training at Winter Haven, Florida. He batted .400 in exhibition games. He spent the season playing for Triple-A Pawtucket (.276), with a call-up to the Red Sox in September. Nichols recalled hitting a slump in Pawtucket. “I was batting .188 and I wasn’t having any fun,” he said. “I went out and bought some cowboy boots and cowboy hat and I showed up to the stadium wearing it and decided it was time to have fun playing baseball again, and after that I improved.”6 He made his major-league on September 16 at Fenway Park, playing center field and batting leadoff. He collected his first major-league hit, a fourth-inning single off Cleveland’s Ross Grimsley. He appeared in 12 games, batting .222 with three RBIs.

Nichols spent all of 1981 with the Red Sox, the first of four-plus seasons with the team. He backed up outfielders Rick Miller, Jim Rice, and Dwight Evans. He played in 39 games, with 55 plate appearances, and batted .188. After his rookie season, there was a lot of anticipation in the local press about what 1982 had in store for Nichols. He told the Boston Herald during 1982 spring training, “The only goal I set is to be the best player I can be. … I want to play every day at 120 percent. I’d like to have some more playing time because experience is the best teacher. I can be a better player just by playing.”7

Nichols did get some more playing time in 1982 and won the praises of manager Ralph Houk, who told The Sporting News in July, “[E]very time he’s played, he’s done well. … And when he’s on the bench he’s an asset with his speed if I need a pinch runner.”8 He hit his first major-league home run in Seattle on May 28, a solo shot off Floyd Bannister in a 3-2 Red Sox victory. His success against Seattle continued in August. On the 23rd in Seattle, Nichols came to the plate against Mariners closer Bill Caudill with the Red Sox down 3-2 and Dave Stapleton on first base. Nichols hit a home run to deep left field and the Red Sox won, 4-3. The next night he homered twice, off Bob Stoddard with a man on in the fourth, and the game-winner off Caudill in the top of the 10th for a 5-4 Red Sox victory.9 For the season, Nichols batted .302 in 265 plate appearances.

It was expected that Nichols would make his way into the starting lineup in 1983, but the Red Sox acquired Tony Armas from the Oakland Athletics in the offseason and Armas became the starter. Nichols was playing in the Dominican Winter League when he learned about the trade. He told the Hartford Courant, “I was disappointed.”10 He told the Waterbury Republican, “I’m content with whatever I get to do. I’m going to do whatever I can to help this club, and I’m not going to complain about anything,” adding, “We’ve got a good outfield, but you never know what could happen, and I’ll be ready to go in there when I’m needed, just like last year.”11

Nichols remained positive and played consistently during the 1983 season, appearing in 100 games, hitting .285, and earning himself a five-year contract at the end of the year. Nichols remained in his reserve role for 1984, playing less frequently and less successfully (.226 in 141 plate appearances). In July 1985 he was traded to the Chicago White Sox for pitcher Tim Lollar. He hit a home run in his final at-bat as a member of the Red Sox on July 10, against the Oakland Athletics, joining Ted Williams among others who achieved this feat for the team.

After the trade, Nichols played more regularly with the White Sox, appearing in 51 games over the rest of the season, compared with just 21 during the first half with the Red Sox. On August 4 he caught the final out of Tom Seaver’s 300th win on a fly out to left field by Yankees pinch-hitter Don Baylor.12

Nichols came to a White Sox team that was in transition. Manager Tony La Russa was fired in June with the team at 26-38. Nichols batted .228 in 74 games. He was released by Chicago at the end of spring training in 1987. A few days later, he signed with the Montreal Expos.

The Expos’ star left fielder, Tim Raines, was a free agent, and Nichols was brought in to fill in until Raines’s contract was resolved. He had a good season, playing in 77 games and batting .265 while remaining a dependable defense presence in the outfield. Nichols enjoyed playing in Montreal, saying, “[T]here wasn’t as much pressure there. We had a good team that year and after the games, there would be 12 guys going out to dinner together.”13

Nichols was released after the season. He finished his eight-season major-league career with 540 games played and a .266 batting average with 63 doubles, 22 home runs, 131 RBIs, and a .716 OPS. In the outfield, he had a .990 fielding percentage and 28 assists.

Nichols spent his final season as a player in 1988 with the Triple-A Oklahoma City 89ers, an affiliate of the Texas Rangers. He retired after the season and got his license to become a fishing charter boat captain. After doing that for a while he realized that “when you own your own business, the customer is the boss and that is a lot of pressure.”14 He gave up his business and decided to go back to baseball, this time in the front office.

Nichols knew Roland Hemond from his time in Chicago, and he had made a good impression on Hemond after returning some extra money that was accidentally reimbursed to him by the team. Hemond was by now general manager of the Baltimore Orioles and hired Reid to work with Doug Melvin, the team’s player personnel director, as a coach and field coordinator.15

When Melvin left Baltimore in 1994 to go the Texas Rangers, he made Nichols the club’s farm director. While with the Rangers, Nichols implemented a career development program for young players to teach them financial literacy and planning, and etiquette. This included hiring actors and going through 18 vignettes with players to see how they would react in different situations. “If a player walks into a bar on a road trip, everyone knows who they are,” said Nichols. “It’s important they know how to handle themselves in that situation.”16 The Wall Street Journal visited the program and did a front-page article about it on March 2, 1998, headlined “Pro Team Covers All It [sic] Bases With Rookie Education Course.”17 In 2001 Nichols was the first-base and outfield coach for the Rangers before leaving at the end of the season to become the director of player development for the Milwaukee Brewers in 2002.

His tenure with Milwaukee included the developing of future stars Ryan Braun, Khris Davis, Scooter Gennett, and Prince Fielder. In a 2014 interview with FanGraphs, Nichols said, “Our basic philosophy is to help make that bridge from the minor leagues to the major leagues as smooth as possible,” adding, “We try to let the players — in their first year — go as far as they can go, doing what they’ve been doing. They’ve obviously done something to get drafted and we don’t want to interfere with that unless we need to. When they get to instructional league — or if they’re struggling during the season and come to us asking for help — we’ll try to make a change. We work more on the mental side when we first get them.”18 Nichols stayed with the Brewers for 13 years and retired in 2015. In addition to moving players up through the different levels of the minor leagues, he was also in charge of letting players know when they were cut. He said, “I like to have a good impact on a young person’s life. If someone wasn’t going to make it in the big leagues, I felt like we were doing them a favor to help them get their life going outside of baseball. I would sit with them all and talk to them about it.”19

After retiring, Nichols worked with USA Baseball and Major League Baseball to help run camps for minority youths during the spring and summer. The camps were held in Vero Beach, Florida, and featured players ages 13-15 in the first week, and players 16-18 in the second week. He started as a coach and then began running the entire operation, overseeing the logistics and managing the staff. “I really enjoyed coaching,” he said. “It’s the same successful feeling as playing when you see someone get what you’re teaching them.”20 He spent three years working for the camp, then officially retired in 2018.

As of 2020 Nichols lived with his wife, Elaine, in Goodyear, Arizona, and spent his spare time hunting, golfing, and fishing. Nichols has three daughters, Amanda, Erin, and Kendall, from a previous marriage.

Last revised: January 7, 2021

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Bouton.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Reid Nichols, telephone interview, June 26, 2020.

2 Nichols interview.

3 Nichols interview.

4 Nichols interview.

5 John Montague, “Nichols Falls One Shy of Carolina Hit Mark,” September 15, 1979. Unidentified newspaper article in Nichols’ player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6 Nichols interview.

7 Steve Harris, “Nichols Just Wants to Play,” Boston Herald, March 11, 1982, from player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

8 “Nichols Is Getting Houk’s Attention,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1982: 22.

9 Dick Trust, “Reid Nichols: A Gold-Plated Fill-In for the Sox,” Quincy (Massachusetts) Patriot Ledger, August 26, 1982, from player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

10 Tom Yantz, “Red Sox’ Plans for Nichols Change,” Hartford Courant, March 29, 1983: C1.

11 P.J. Conway, “Boston’s Nichols Ready to Help in Reserve Role,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Republican, March 22, 1983: C1.

12 “CWS@NYY: Seaver Gets His 300th Career Win,” MLB YouTube Page, https://youtube.com/watch?v=5XW3YNn9-jQ

13 Nichols interview.

14 Nichols interview.

15 Nichols interview.

16 Nichols interview.

17 Scott Mccartney, “Pro Team Covers All It [sic] Bases With Rookie Education Course,” Wall Street Journal, March 2, 1998. https://wsj.com/articles/SB888847813594614500.

18 David Laurila, “Q&A: Reid Nichols, Milwaukee Brewers Director of Player Development,” FanGraphs, November 25, 2014. https://blogs.fangraphs.com/qa-reid-nichols-milwaukee-brewers-director-of-player-development/.

19 Nichols interview.

20 Nichols interview.

Full Name

Thomas Reid Nichols

Born

August 5, 1958 at Ocala, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.