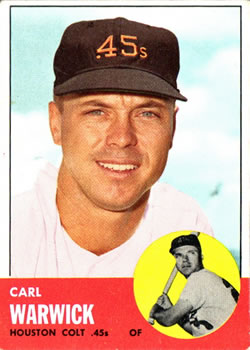

Carl Warwick

To many baseball fans, especially those in St. Louis, Carl Warwick will be best remembered for being a hero off the bench in the 1964 World Series. After spending the regular season as a reserve outfielder and bat off the bench, Warwick excelled in the postseason and whacked a record-tying three pinch hits that played key roles in two of the Cardinals’ victories as they vanquished the New York Yankees in seven games.

To many baseball fans, especially those in St. Louis, Carl Warwick will be best remembered for being a hero off the bench in the 1964 World Series. After spending the regular season as a reserve outfielder and bat off the bench, Warwick excelled in the postseason and whacked a record-tying three pinch hits that played key roles in two of the Cardinals’ victories as they vanquished the New York Yankees in seven games.

Carl Wayne Warwick was born on February 27, 1937, in Dallas, Texas. The son of an auto mechanic, he began playing organized baseball at the age of 9 and was always an outfielder, except for a short stint at first base in high school.1 After graduating from Sunset High School in 1955, Warwick attended Texas Christian University on an athletic scholarship.

More famous as TCU’s football coach, Dutch Meyer coached the baseball team for one season during Warwick’s freshman year and led the Horned Frogs to the Southwest Conference championship. That season, Warwick was named to the All-Conference team and the NCAA All-American third team. As a sophomore, Warwick led TCU with a .321 batting average and attracted the attention of Los Angeles Dodgers scout Hugh Alexander.

Warwick turned to Meyer for advice after the Dodgers promised him a $25,000 signing bonus before his senior year.2 Meyer advised Warwick to accept the money, as it was a significant amount at the time, and said Warwick need not feel any obligation towards the university. After spending two weeks struggling with the decision, Warwick decided to forgo his senior season and signed with the Dodgers.

Despite his 5-foot-10, 170-pound frame, Carl began to cultivate a reputation as a power hitter during his first minor league season. Playing for Macon of the South Atlantic League in 1958, Warwick hit .279 with 29 doubles and led the Sally League with 22 homers. The following year, starring for the Victoria Rosebuds, Warwick was named the Texas League’s Most Valuable Player. The Dallas native hit .331 and led the league in home runs (35), total bases (324) and runs scored (129), and was second in stolen bases (18). Warwick didn’t rest during the offseason, traveling to the Dominican Republic where he played in the winter league for Escogido.

Warwick earned a promotion to St. Paul of the American Association for the 1960 season. He hit .292 with 27 doubles, 11 triples, 19 home runs, 75 RBIs and 18 stolen bases. Warwick also had a fine year defensively and led the league’s outfielders in putouts and assists.

Warwick was invited to spring training with the Dodgers in 1961 and had an impressive camp, hitting over .400. There appeared little chance to break into the veteran Dodger outfield of Wally Moon, Willie Davis, and Frank Howard, and the Dodgers also had strong reserves in Tommy Davis, Ron Fairly, and Duke Snider. However, Warwick overcame these odds and was named to Los Angeles’ Opening Day roster. He made his major-league debut on April 11, 1961, against the Philadelphia Phillies at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. With the Dodgers leading 5-2, manager Walter Alston sent Warwick to pinch hit for Moon in the eighth inning. Facing Philadelphia reliever Ken Lehman, Warwick singled to left field, scoring Willie Davis. He would always remember this hit as his favorite major-league thrill, although later he would recall in an interview, “Funny thing, I can’t remember the pitcher’s name.”3

Playing time was in short supply with Los Angeles’ deep roster and Warwick was used primarily as a pinch runner or defensive replacement for Moon, appearing in 19 games, but only registering that first hit in 11 at-bats. On May 30, 1961, Los Angeles traded Warwick to the St. Louis Cardinals with shortstop Bob Lillis for shortstop Daryl Spencer. Warwick later reflected, “I was just there at the wrong time. The Dodgers started the year with three outfielders and all three did well, so naturally they were hesitant to make a change. I don’t have any complaints about the way I was treated by the Dodgers.”4

His debut for the Cardinals came the same day he was acquired, as Carl didn’t have to travel very far to reach his new teammates – only across the halls of Memorial Coliseum to the visitor’s clubhouse. Warwick came into the game in the bottom of the seventh inning as a defensive replacement for right-fielder Joe Cunningham. He came to bat in the ninth and drew a walk off former teammate Stan Williams.

The Cardinals demonstrated their faith in Warwick immediately, as they thrust him into the starting lineup for the team’s next 22 games, usually in center field, which included four doubleheaders. He hit his first major-league home run on June 3 to deep left against Bob Buhl of the Milwaukee Braves during a 9-3 loss. However, playing time dwindled as the season progressed. To keep him fresh, the Cardinals sent Warwick to San Juan/Charleston of the International League where he hit .289 in 204 at-bats. He returned to St. Louis in mid-September and went 8-for-18, finishing with a .239 batting average, .317 on-base percentage and four home runs.

Warwick began the 1962 season on a hot streak, going 8-for-23 (.348), but would not have another hit for the Cardinals for nearly two years. On May 7, he was dealt to Houston with relief pitcher John Anderson for pitcher Bobby Shantz. Warwick wasn’t displeased at the move, feeling he was in St. Louis “at the wrong time” given the presence of Curt Flood, Charlie James and Stan Musial in the outfield.5

With the expansion Colt .45s, Warwick became an everyday starter for the first time in his major league career. He finished the season batting .264 and totalled 17 doubles, 17 home runs, and 64 RBIs. Warwick’s 16 homers for the Colt .45s were second on the team and his season total of 17 was more than half his career total of 31. However, Carl believed he focused too much on hitting for power and admitted, “I wanted to hit 20 home runs and it probably cost me 20 or 30 points on my batting average.”6 He was popular with teammates and coaches in Houston and Colt .45s manager Harry Craft praised Warwick’s willingness to listen and learn, calling him “a darned good subject.”7

Warwick finished his career with 31 home runs, but in his mind it should have been 32 because of a missed call on May 3, 1963. In the top of the fifth inning, Warwick hit a double and went to third on the throw to the plate. According to an article that appeared in The Sporting News two weeks later, Harvey Pinsk, a Philadelphia high school student sitting in the front row at Connie Mack Stadium, admitted he tried to catch Warwick’s line drive and it deflected off his hand back onto the field. Pinsk stated, “Sure, it was a home run. I leaned over to try and catch the ball, but it hit my hands and then glanced off the stands before falling back on the field.”8 Warwick didn’t score and the Colts went on to lose the game 4-3.

On February 17, 1964, Warwick was traded back to the Cardinals in exchange for first baseman/outfielder Jim Beauchamp and pitcher Chuck Taylor. Warwick’s defensive reputation appeared to have decreased over the past few seasons, as Cardinals general manager Bing Devine only characterized it as “adequate,” but he was hopeful Warwick could contribute more offensively in St. Louis than he did in Houston, as Colt Stadium was a difficult park for hitters, due to long fences, imperfect lighting and the fatigue of playing in the Texas heat during the summer.9 Devine was optimistic about the way the Cards could utilize him, saying, “Warwick could play full time or part time, he could be platooned or he could be valuable as a pinch-hitter.”10 That latter comment would prove to be very prescient.

As in 1963, Warwick began 1964 on a tear at the plate. However, a tragedy struck the family, as his wife’s 17-year-old sister died of an unexpected heart attack in a Houston high school on May 20.11 Carl left the team to be with the family and didn’t play again for a week. As the season progressed, Warwick’s playing time dwindled as the starting outfield solidified with the arrival of Lou Brock in a trade and Mike Shannon’s emergence as the everyday right fielder. After playing six full games between June 2 and June 12, Warwick only played three complete games during the rest of the season, as he fell behind Charlie James on the depth chart and was confined to the corner outfield positions and pinch-hitting appearances. On September 27, he had his cheekbone fractured on a fungo hit by reliever Ron Taylor and had it promptly operated on in a St. Louis hospital.

Warwick finished the season with a .259 batting average in 158 at-bats, going 11-for-41 as a pinch-hitter with a pair of walks and pair of sacrifices. He credited his success in those situations to a new aggressive approach, developed with the help of two of his teammates. “I seem to carry a different attitude up there coming off the bench. I wouldn’t call it confidence. I come up there swinging. You’ve only got three swings. I don’t want to pass up an opportunity.” He continued, “Early in the year I was nervous pinch hitting. Then I got talking with Red Schoendienst and Jerry Lynch…Both of them agreed you’ve got to be ready to attack the ball. Now I enjoy it. I begin to sense on the bench when my time is coming and I get anxious. When the time comes, I’m swinging.”12 Pinch-hitting success had eluded the Cardinals during their previous nine World Series appearances, however, as Cardinals batters were 8-for-42 in pinch-hit at-bats during that time.

Warwick was on the bench for Game One of the World Series as Ray Sadecki faced Whitey Ford of the New York Yankees. With the score tied 4-4 in the bottom of the sixth inning, Warwick was summoned to hit for Sadecki with the go-ahead run on second base and two down. Warwick drove a single to left off Al Downing that scored Tim McCarver and gave St. Louis a lead it would not relinquish, as Barney Schultz picked up a three-inning save in a 9-5 victory.

Bob Gibson faced Mel Stottlemyre in Game Two at Busch Stadium I. With the Yankees leading 4-1 in the bottom of the eighth, Warwick led off the frame by batting for Dal Maxvill and singled off Stottlemyre. Warwick eventually scored on a grounder by Brock. However, New York won the game, 8-3.

The series shifted to New York for Game Three and St. Louis’ Curt Simmons faced Jim Bouton. The pitchers’ duel was tied 1-1 when Warwick was again called on to hit for Maxvill in the ninth, with McCarver standing on second and one out. Warwick coaxed a walk off Bouton, but St. Louis didn’t score in the inning and New York won the game in the bottom of the frame with a walk-off home run by Mickey Mantle.

Warwick’s contribution in Game Four didn’t change the game as obviously as his hit in Game One, but it was an important at-bat in the most crucial inning of the game. The Cardinals fell behind 3-0 early, but reliever Roger Craig pitched four and two-thirds innings of scoreless relief. In the sixth inning, manager Johnny Keane chose to pull Craig and summoned Warwick to pinch-hit. Warwick singled off Downing, who had only allowed one bloop single in the game until that point. Curt Flood singled, Dick Groat reached on an error, and Ken Boyer unloaded a grand slam that gave the Cardinals a 4-3 lead. Ron Taylor combined with Craig to hold the Yankees to one single over the last eight innings and the Cardinals won 4-3, While Boyer had won the game with a grand slam, Bob Skinner said, “[Warwick’s single] began to turn the game around.”13

Warwick’s third pinch hit tied the record for pinch hits in a World Series, held by Bobby Brown and Dusty Rhodes. (Since then the record has also been tied by Gonzalo Marquez and Ken Boswell.) However, even his feat didn’t eclipse the memory of his first big-league hit, as Warwick still harkened back to “Opening Day, 1961, before 60,000 in the Coliseum” as his favorite memory.14

For the first time all series, Warwick didn’t make it off the bench in Game Five, as Gibson threw 10 strong innings in an extra-inning 5-2 victory. The Yankees forced a seventh game with an 8-3 victory in Game Six and in that game they were finally able to keep Warwick off the bases in his fifth plate appearance of the Series. Warwick hit for Maxvill in the seventh inning, but fouled out to third base off Bouton. Gibson was brought back on two days rest to start Game Seven, and he pitched another complete game. The Cardinals scored three runs in the bottom of both the fourth and fifth innings on their way to a 7-5 victory and a World Series championship. Afterwards, Keane praised Warwick’s pinch-hitting ability and said he was better suited to coming off the bench, because he was more aggressive as a pinch-hitter but took too many pitches as a starter.

Following that spectacular end to the season, Warwick returned to Houston, where he and his family lived in the offseason. During the winter, Warwick had a career as a manufacturer’s representative for a paint company, but he was grateful he was able to spend more time with his wife, the former Nancy Hemsler, and daughters Karla and Julie.15 Nancy was active in several charity ventures, such as when she teamed up with other baseball wives to produce the 1966 Houston Pinch-Hitters charity dinner, dance, style show and revue benefit for the Council for Minimally Brain Injured Children. The charity venture was held at the Houston Club, with Nancy heading the models’ committee and Carl participating in a skit.16

As the 1965 season began, Warwick appeared ready to serve as the primary outfield reserve with the ability to start in right field should Mike Shannon falter. His strong World Series performance was fresh in everyone’s mind and Warwick also offered defensive versatility and a positive attitude, as he did not complain over a lack of regular playing time.

However, as well as the 1964 season finished, 1965 began that poorly. Warwick struggled from the beginning and Tito Francona, an offseason acquisition from the Cleveland Indians, and Bob Skinner jumped ahead of him on the depth chart. Warwick found consistent playing time was difficult to come by. After playing the entire game at first base on May 7, Carl played in only seven full games over the next 2½ months, and six of those came between June 9 and 14.

On July 24, hitting only .156, Warwick was sold to the Baltimore Orioles for cash considerations. Manager Hank Bauer tabbed Warwick to be one of Baltimore’s primary pinch-hitters and said that he might get some starts against left-handed pitching. Although the Cardinals were in Los Angeles at the time of the trade, Warwick made it to Baltimore for that evening’s game against Minnesota, where he made a pinch-hitting appearance.

However, Warwick’s only stint in the American League was perhaps the least enjoyable of his big-league career. He was hitless in 14 at-bats, although he drew three walks and scored three runs. Carl made only three starts and went 0-for-6 as a pinch-hitter. Warwick spent the last month and a half of the season on the end of the Orioles bench; his only playing time after August 13 was one pinch-hit appearance.

Warwick thought Baltimore would move him after the 1965 season. In an October interview he said, “I guess [Baltimore] will get rid of me.” He recounted a conversation with his manager: “I asked Bauer what his plans were for me and he said I’d be the fifth or sixth outfielder. I asked him if I’d get a chance to play in spring training and he said, ‘No.’” Warwick was upset, remarking at the time, “This is the first club I’ve ever been on where I won’t even get a chance to try and win a job in spring training. I don’t know why they bought me if they didn’t intend to use me.”17

The trade Warwick was waiting for eventually arrived, as Leo Durocher acquired him for the Cubs on March 31 for catcher Vic Roznovsky. Warwick was acquired to provide competition for George Altman in left field and solidify Chicago’s bench. Durocher spoke glowingly about Warwick’s defensive versatility, stating, “He gives us insurance at both [center and left]” and also praised his speed and throwing accuracy.18 At this point, Warwick was the only major leaguer listed to bat exclusively right-handed and throw left-handed.19

Despite Durocher’s comments, it soon became evident that Warwick would be utilized solely as an outfield reserve and a pinch-hitter. He started four games in April, all in center field, and finished the month with two singles in 13 at-bats. He appeared in three games in May and struck out in both of his at-bats. After going 2-for-7 in early June, Warwick entered his final big-league game on June 12, as the Cubs visited the Astrodome. He replaced Adolfo Phillips in center field with one out in the bottom of the sixth, immediately after Rusty Staub had hit an inside-the-park homer to center. His final big-league at-bat came in the eighth against Dave Giusti, and Warwick singled and later scored. On June 15, 1966, three days after his final hit, he was optioned to Dallas-Forth Worth and never played in the majors again. He hit just .140 as a pinch hitter during 1965 and 1966 after his three hits in the 1964 World Series.

Warwick played 43 games with Dallas-Fort Worth and hit .248 with six home runs and 26 RBIs. On August 1 he was assigned to the Tacoma Cubs of the Pacific Coast League, where he struggled, hitting .212 in 113 plate appearances with a pair of homers. At the end of September, the Cubs assigned Warwick outright to the Jacksonville Suns. Warwick signed a minor-league contract with the Mets in the offseason and was invited to spring training. However, he chose to retire on March 1, 1967, just a few days before he was to report to Florida.

After his career ended, Warwick returned to Houston and started a real estate company named Carl Warwick & Associates. Later, he started a travel company called Questar Travel, dealing mostly with corporate travel, which he continues to own and operate. Warwick also served as Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Major League Baseball Alumni Association, which raises funds for charity.

Warwick’s retirement has been busy, as he is also active in the baseball community at the local and state level. He is involved with the Karl Young Baseball League, an MLB-sanctioned summer baseball league for college-age baseball players and is involved with college baseball in Houston, such as when he arranged a meeting between former Astro Terry Puhl and the vice president of the University of Houston-Victoria which led to Puhl being hired as the university’s head baseball coach.20 Warwick also serves as a board member for the Harris County-Houston Sports Authority and as an advisory board member for the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame. He founded and chairs the Milo Hamilton Golf Classic, honoring the Astros broadcaster. Warwick was elected to the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame in 1990 and the Texas Christian University Letterman’s Association Hall of Fame in 1959.

In one survey of major league players, Carl listed his favorite hobbies as golfing and fishing, although he also mentioned he enjoyed playing the piano and trumpet, and also noted that he did all of these activities right-handed.21 His hobbies continued into retirement, and he also find pleasure working with Little League baseball players. However, his favorite activity is spending time with his wife, Nancy, his two children and four grandsons.

This biography is included in the book “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1Wizig, Jerry. “It’s Warwick Wielding That Hot Bat.” Houston Chronicle. May 21, 1963.

2 Broeg, Bob. “Warwick Was Ready for War on Yanks When Keane Said ‘Scramble.’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 12, 1964.

3 Ibid.

4 Wizig, Jerry. “It’s Warwick Wielding That Hot Bat.” Houston Chronicle. May 21, 1963.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Lewis, Allen. “Warwick Claims HR Despite Veto by Ump.” The Sporting News. May 18, 1963.

9 Ibid.

10 Russo, Neal. “Warwick’s Return Bolsters Cardinals’ Outfield Corps.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 29, 1964.

11 Broeg, Bob. “Warwick Was Ready for War on Yanks When Keane Said ‘Scramble.’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 12, 1964.

It is listed as “Hemsler” in the newspaper article, but an online link at the Harris-County Sports Authority lists the wife’s name as “Hensler.”

12 Donnelly, Joe. “Alas, Warwick, the Yanks Know Him.” October 12, 1964. Red Schoendiest set the NL record for pinch-hits in a season with 22 in 1962 – and he could have had 23 except for a base-running mistake

13 Ibid.

14 Broeg, Bob. “Warwick Was Ready for War on Yanks When Keane Said ‘Scramble.’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 12, 1964. The actual attendance has been reported as 50,927.

15 Gallagher, Jack. “Big Timers Pick Hearths in Houston.” The Sporting News. December 5, 1964.

16 Ibid.

17 Associated Press. “ ‘No Chance to Try,’ Says Warwick.” October 16, 1965.

18 Dozer, Richard. “Cubs Trade Roznovsky for Warwick.” Chicago Tribune. April 1, 1966.

19 Ibid.

20 Boughton, Bob. “Interview with Team Canada/Houston-Victoria Head Coach Terry Puhl.” The College Baseball Blog. August 25, 2008. (http://thecollegebaseballblog.com/2008/08/25/interview-with-team-canadahouston-victoria-coach-terry-puhl/) Accessed: August, 2009.

21 Broeg, Bob. “Warwick Was Ready for War on Yanks When Keane Said ‘Scramble.’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 12, 1964.

Full Name

Carl Wayne Warwick

Born

February 27, 1937 at Dallas, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.