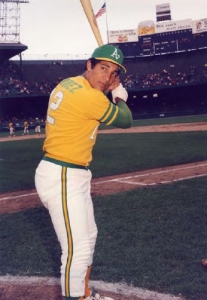

Gonzalo Márquez

Gonzalo Márquez, one of the earlier Venezuelans in the majors, never played a full year in “The Show.” From 1972 through 1974, he got into just 76 regular-season games with Oakland and the Chicago Cubs. Márquez’s primary position was first base, and he was a good fielder — but he lacked power. Across his entire pro career, including play in the postseason and Latin American leagues, he hit home runs once in every 132 at-bats.1

Gonzalo Márquez, one of the earlier Venezuelans in the majors, never played a full year in “The Show.” From 1972 through 1974, he got into just 76 regular-season games with Oakland and the Chicago Cubs. Márquez’s primary position was first base, and he was a good fielder — but he lacked power. Across his entire pro career, including play in the postseason and Latin American leagues, he hit home runs once in every 132 at-bats.1

Márquez was a contact hitter. He averaged exactly .300 in the minors and .288 during 20 seasons of winter ball in his homeland. Thus, he made his mark in postseason play as a pinch-hitter. During the 1972 AL Championship Series against Detroit, he was 2-for-3. He won Game One with a single in the 11th inning and scored a go-ahead run after singling in the tenth inning of Game Four. Márquez continued to deliver off the bench in the World Series, going 3-for-5. In Game Four, he ignited the game-winning rally in the bottom of the ninth.

Márquez played his last season in the US minors in 1974. He then spent two years in the Mexican League (1975 and 1978), followed by a stint in the short-lived Inter-American League of 1979. After that, he played on with the Caracas Leones of the Venezuelan League, his team for nearly all his career at home. He became a respected leader and was serving as a player-coach when his life was cut short in a postgame car accident in December 1984.

According to most baseball references, Gonzalo Enrique Márquez Moya was born on March 31, 1946. However, his birth certificate shows that the true date was March 31, 1940. He presented an ID that showed 1946 when he turned professional.

Márquez’s birthplace was Carúpano, a small city in the state of Sucre. Sucre is in the northeastern part of Venezuela, along the coast of the Caribbean Sea. It has much natural beauty, including beaches — Carúpano’s are lovely — and mountains. Carúpano is also famous for its annual carnival, the biggest of its kind in the nation. The Lonely Planet travel guide to Venezuela describes it as “quite possibly the most lively, boisterous, and crazy rave you’ll ever experience.”

Sucre is one of the poorer and less developed states in Venezuela. The local economy of Carúpano relies on trade and shipment of commodities, cocoa in particular. Gonzalo Márquez’s father, Jesús “Chuíto” Márquez, was a merchant (the family also owned some farmland).2 His mother, Edelmira Moya, was a dressmaker and housewife looking after six children (four brothers and two sisters), of whom Gonzalo was the second.

Márquez had happy memories of growing up in Carúpano. In 2012, Venezuelan baseball author Alfonso Tusa wrote, “I can’t remember exactly whether it was in Sport Gráfico magazine or in a radio interview that I heard Gonzalo Márquez say that what he missed most from home were the arepas [a South American corn cake] with fresh mussels that were sold in the municipal market.” Márquez also enjoyed playing the guitar and painting on canvas.3

Márquez developed his skills in amateur baseball with a club called Vigilantes. His professional baseball career began in the winter of 1965-66, when he joined the Caracas Leones after receiving an offer from club owners Pablo Morales and Óscar “El Negro” Prieto. The nation’s capital is about 250 miles west of Carúpano (as the crow flies). That team had a working agreement with the Athletics organization, then still based in Kansas City. As a result, Félix “Fellé” Delgado, the Latin American regional scout for the A’s. also signed him. He gave Márquez the nickname “Hurricane,” though Gonzalo never knew why.4

The Leones then featured two of the all-time Venezuelan baseball heroes, Vic Davalillo and César Tovar. The 1965-66 squad also included several young A’s. Pitchers Lew Krausse and Paul Lindblad led the staff, which also included 19-year-old Jim Hunter until he had to leave with a sore arm.5 The shortstop was Bert Campaneris. Márquez got into 19 games, getting more of an opportunity after Caracas fired Ken “Hawk” Harrelson for playing golf when he was supposedly ill.6

Márquez played in the US for the first time in 1966. The lefty swinger spent three seasons at Class A, hitting for a nice average (.297) but with little extra-base pop (slugging percentage of .352, and just one homer). He also showed some base-stealing ability, swiping nine in ten games after becoming a leadoff hitter during the 1968 season.7

According to Alfonso Tusa, Márquez had an excellent glove at first base. He wasn’t tall (5-feet-11), but he had quick reactions and was especially good at saving wild throws. Further support for Márquez’s skill in the field comes from Jesús “Chalao” Méndez, who played in the US minors, Mexico, and Venezuela in the 1980s and 1990s before becoming chief scout in Venezuela for the Philadelphia Phillies. Méndez never reached the majors; like Márquez, he was a flashy fielder with very little power — “a shortstop who played first.” In a 2010 interview, he called Márquez “my all-time idol” and “a guide for me to play first base.”8

Márquez also developed enough with the bat to become the regular first baseman for Caracas in his second winter with the team, 1966-67. The Leones won the league championship that year and again in 1967-68, when Márquez hit a career-high .354 and tied a league record with eight RBIs in a playoff game on February 4. He eventually became a member of eight title winners at home.

In 1969 Márquez moved up to Double-A Birmingham. He had another pretty fair year (.297-3-34, .372 slugging percentage) but received no particular attention in The Sporting News. That December, he married Hercilia Rísquez. He also drew plans for the Venezuelan national telephone company while playing winter ball.9

A special career highlight for Márquez came in February 1970. After playing for Caracas in the regular winter season, he joined Navegantes de Magallanes to reinforce their roster for the playoffs (a common winter-league practice). Magallanes won the championship and thus went on to represent Venezuela in the Caribbean Series, which had been revived after a hiatus of nine years. The tournament was held in Caracas, and Venezuela took seven of eight games in the round-robin against the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. It was the nation’s first Caribbean Series title. Márquez led all hitters with his .478 average (11-for-23) and was named series MVP.

Coming off this performance, Márquez earned another promotion in 1970. With Iowa of the Triple-A American Association, he had his best season as a pro (.341-6-60, .430 slugging). Márquez, who hit primarily to the opposite field or up the middle, benefited from manager Sherm Lollar’s advice. Lollar said, “The defenses were beginning to play him like a right-handed pull hitter. I suggested that he keep ’em honest by taking a shot to that open area in right.”10

During the summer of 1971, Márquez sat out the entire season. Reports varied as to why; one said he held out, another said he had a leg injury.11 In 1972, though, Márquez himself said that he was taking care of his mother, who was very sick with gangrene in one foot. He later said, “It was a long year.”12 He returned in 1972, however, and displayed his usual contact hitting at Iowa (.309-0-27). Márquez was not unusually hard to strike out, but he did not walk very much either.

In August 1972 Márquez — thought to be aged 26, but really 32 — got his first call to the majors. He made his debut on August 11 and struck out as a pinch-hitter against Cecilio “Cy” Acosta of the Chicago White Sox. He was just the 21st Venezuelan to appear in a big-league game.

Márquez did almost nothing but pinch-hit for the A’s in 1972. Out of his 23 appearances, one came as a pinch-runner, and he stayed in the game at first base. His only start came in the season’s last game. Overall, he was 8-for-21 (.381) with four RBIs.

Oakland put Márquez on the postseason roster — but he wasn’t on the original list of 25 players that the team submitted. He had a plane ticket for Venezuela at the end of the regular season.13 However, when reliever Darold Knowles broke his left thumb, manager Dick Williams chose Márquez to replace Knowles instead of lefty pitcher Don Shaw.14 The skipper’s thinking was something that would be unheard of today. “I added [Márquez] then,” said Williams, “because I was quite content using eight pitchers in the playoffs and I wanted another bat to use with our second base situation.”15 The skipper was referring to the strategy of pinch-hitting for the club’s light-hitting second basemen whenever they came up.

The decision to bring Márquez paid immediate dividends in the ALCS. In Game One, veteran Tigers star Al Kaline had given Detroit a 2-1 lead with a home run in the top of the 11th. In the bottom of the inning, Márquez came up with runners on first and second. He ripped a single to right off Chuck Seelbach, past a diving Norm Cash. The tying run scored and the winning run followed when Kaline made a throwing error. “It was the biggest hit of my life,” said Márquez, through translator Bert Campaneris.16 Previously he had told Campy, “If I get a chance to hit, I win the game.”17

Márquez also started what could have been a game-winning rally in the tenth inning of Game Four. He scored with a diving slide that knocked the ball loose from Tigers catcher Bill Freehan, but had the wind knocked out of him. As a result, he did not remember rolling over to touch the plate. In the bottom of the tenth, though, three Oakland pitchers combined to give up a two-run lead. Márquez rubbed his aching chest as he was interviewed but said, “I can play if it’s only as a pinch-hitter. Anyway, I want to [play].”18 However, Williams did not call on his rookie as Oakland won Game Five and advanced to the World Series.

Against Cincinnati, Márquez was 1-for-2 in his first two appearances off the bench. Neither of those influenced the game’s outcome — but the finest moment of his big-league career came in Game Four. Oakland trailed 2-1 going into the ninth inning. Williams sent Márquez up to pinch-hit for George Hendrick with one out and the bases empty. Reds manager Sparky Anderson later recalled, “The information which Ray Shore had provided on Márquez in his scouting report was right on the money. If we had followed it, we would have won that game — and the Series.

“The report said to bunch Márquez down the middle. That was where he hit the ball in any games that Shore saw him play. It just happened, though, that [Dave] Concepción, our shortstop, had played against Márquez in Venezuela.

“Dave told us, ‘Skip, this guy hits everything to left.’ As Alex Grammas, my infield coach, pointed out, Concepción had more opportunity to see Márquez than Shore had.”

The account by Toronto Star columnist Milt Dunnell continued, “Márquez hit a high hopper over the hill. If Concepcion had been playing where the scouting report recommended, he would have taken the ball in his hip pocket. He almost made the out anyway.”19 The game-winning rally then unfolded. After spending the winter second-guessing himself, Anderson was still blaming himself for the decision in 1975.20

Márquez appeared twice more during the rest of the World Series. In Game Six, he got his third pinch hit, tying the World Series record then held by three men: Bobby Brown (1947), Dusty Rhodes (1954), and Carl Warwick (1964). Ken Boswell became the fifth (and as of 2013, the last to date) in 1973.

In the winter of 1972-73, Márquez won another championship with Caracas. He then made the Opening Day roster for the A’s in 1973. Again he served almost exclusively as a pinch-hitter. The American League adopted the designated-hitter rule that year, but Márquez got just one start there — owner Charlie Finley thought the singles hitter didn’t fit the bill.21 He also was listed as the starting second baseman in back-to-back games on May 4 and 5. The first time, Márquez thought it was a joke.22 On both occasions, though, Dick Green — a true second baseman — replaced him in the field in the bottom of the first inning. The A’s used this strategy on various other occasions.

Márquez played only one inning at his true position for Oakland in 1973. He entered the game on May 18 after Bill North had been ejected for throwing his bat at Kansas City pitcher Doug Bird and charging the mound. Two days later, Márquez also played one inning in right field.

Despite his sporadic duty, Márquez did a fairly good job, going 6-for-23 (.261). The A’s sent him down to Triple-A Tucson in early June, though, recalling pinch-runner Allan Lewis. “We don’t have any use for Márquez as a pinch-hitter with the designated hitter rule,” said Dick Williams.23 Márquez was recalled in August and made two more pinch-hitting appearances. On August 29 Oakland traded him to the Chicago Cubs, even-up for another first baseman, Pat Bourque. A’s beat writer Ron Bergman commented, “Márquez lost his batting stroke through disuse. The A’s then opted for someone with more power, and Bourque was available.”24

In Chicago, Márquez finally got a chance for some regular action, at least against righties. He started 17 games that September, hitting .224. On September 21 at Wrigley Field, he hit his only homer in the majors. It was an opposite-field shot into the basket atop Wrigley’s outfield wall, off Steve Rogers, then a rookie with the Montreal Expos.25

Before Márquez came to the Cubs, the team had given rookie André Thornton and veteran star Billy Williams looks at first base. Thornton played that position most frequently for Chicago in 1974, and Márquez (one of the last cuts after holding out) opened the season at Triple-A Wichita. He got back to the big club in early May, though, when little-used utilityman Adrian Garrett was sent down. Márquez remained with the Cubs through early June. During that month, he got into 11 games in the majors, all as a pinch-hitter. He went hitless in 11 at-bats and played one inning in the field at first. Chicago sent Márquez back to Wichita; he never made it back to the majors. All told, he hit .235-1-10 in 128 plate appearances.

In December 1974 Chicago sold Márquez’s contract to Puebla of the Mexican League. He played in just 24 games for the Pericos in 1975 (.314-1-14); his family remembered that he didn’t want to be separated from them. Márquez did not play during the summers in Mexico (or anywhere else) in 1976 and 1977, though he remained active at home in the winters. Márquez loved to play baseball — it bored him to watch on television. He returned to Mexico in 1978 and had a good year with Tampico. He set a personal high with 12 home runs, while driving in 61 runs and hitting .288 in 135 games.

In 1979 the Inter-American League started up. The IAL had two of its six franchises in Venezuela, which gave Márquez an opportunity to play at home in the summer too. He played 24 games for the Caracas Metropolitanos and two for the Maracaibo Petroleros. However, the ill-starred league folded in June before its first season was complete.

Márquez played with Caracas for another six winter seasons. He had rejoined the Leones in the winter of 1976-77 after one season with Magallanes — the only other time he did not wear a Caracas uniform during the winter. During the regular season in Venezuela, he hit just 16 homers in 833 games and 2,932 at-bats.

Márquez appeared in the playoffs in 14 of his 20 years, though, and as he did in the US, he took his play up a notch in the Venezuelan postseason. He hit .300 with six homers in 96 games and 310 at-bats. He was part of four more league champions: 1977-78, and the “three-peat” teams of 1979-80, 1980-81, and 1981-82.

As a consequence of being on all those teams, Márquez was on hand for five Caribbean Series (the 1981 edition was not held because of a Venezuelan players’ strike). He got to play in three, hitting .387 (24-for-62) overall and making the 1973 tournament all-star team. Winning the Caribbean Series is a matter of national pride, though — even highly regarded native players remain on the bench sometimes. In 1980 the primary first baseman for the Leones was Ken Phelps. In 1982 the great Venezuelan first baseman Andrés Galarraga had played a lot during the regular season. But he was still just 20 and inexperienced, as he graciously admitted.26

So manager Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel used American Danny García in the 1982 postseason, and did so again in Hermosillo, Mexico. The Leones won five of six games there and brought the Caribbean title to Venezuela. García remembered, “I had led the team in hitting. I batted third in the lineup behind Eddie Milner and Steve Sax, followed by Venezuelan greats Tony Armas and Baudilio [Bo] Díaz batting fourth and fifth, with Dave Henderson batting sixth.” He added, “I remember ‘Gonzo’ as a quiet, very smart teammate.”27

Márquez was a mentor to Galarraga. “The Big Cat” played with the Leones for the first time in the 1978-79 season at the age of 17. In 1978 Márquez also helped mold another future Venezuelan star, Ozzie Guillén, then a skinny little 14-year-old. That came as Márquez and his former Caracas teammate Dámaso Blanco managed the national team.28

According to the Associated Press, Márquez also became a scout for the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1983.29 He may have been affiliated with the club years before, though — the book Los Leones del Caracas states that Márquez discovered Leonardo “Leo” Hernández and brought him to Caracas for the 1978-79 season.30 Hernandez, who played in the majors for parts of four seasons in the ’80s, started his US pro career in the Dodgers chain in 1978. In October 1984 Márquez signed another of his countrymen for the Dodgers, Carlos Alberto Hernández. The catcher eventually played in the majors from 1990 through 2000.

Márquez’s family said he had a hand in the signing of Óscar Azócar, another Sucre native. Azócar’s first pro action came with the Leones in the winter of 1983-84; he signed with the New York Yankees in November 1983, originally as a pitcher.31 After converting to the outfield, Azócar made it to the majors from 1990-92.

In the 1984-85 winter season, another of Venezuela’s all-time greats joined the Leones as a youth of 17. That was shortstop Omar Vizquel, coming off his first year as a Seattle Mariners farmhand. Vizquel was another of the young ballplayers who affectionately called Márquez Abuelo, or Grandfather. In 2010, after Óscar Azócar died suddenly, Vizquel said, “His personality reminded me lot of Gonzalo Márquez. He was a very happy person.”32

On December 19, 1984, Caracas played Navegantes de Magallanes in Valencia. Márquez did not have to play because he had some broken toes, but he stayed in the lineup — he was not one to complain. After the game, Márquez got in his car with Julio César, his 16-year-old son from a relationship before his marriage to Hercilia, and 12-year-old Gonzalo Jr., to drive back to the capital city. It was about halfway through the trip, in the city of La Victoria, when tragedy struck. In 1986 Andrés Galarraga told the sad story of what happened. “Some young people in a car were drunk and they came across the road and hit his car. We were right behind him in the team bus. We saw it happen and we had to pull his body out.”33

Julio escaped the accident nearly unscathed, except for a nine-stitch cut in his arm, received as he got out of the car. Gonzalo Jr. was severely injured in the accident but pulled through.34 In 2013 he related another sad twist of fate about the accident. “After the game, we always stopped to eat a pernil [roast pork shoulder] sandwich at a place called La Encrucijada [The Crossroads, a roadside eatery famous throughout Venezuela]. I remember as if it were yesterday that we were blocked by a car parked behind us and my father tried to get out for more than 10 minutes. This happened five minutes before the accident. If that car hadn’t been there, the story would have a happy ending.”

Márquez’s death certificate put the time of death at around 1:00 on the morning of December 20. Several days after the accident, however, his wife, Hercilia, gained access to personal effects and noticed that the crash had caused his watch to stop at 11:45 P.M. on the 19th.

The loss of Márquez — who had helped young players with their skills and kept the team united — affected all the Leones deeply, but Galarraga in particular.35 “He was my best friend,” said El Gato in 1988. “He helped me more than anyone, and when he died I was left alone.”36 Galarraga remained a good friend to the Márquez family.

In addition to Hercilia, Márquez was survived by their four children, as well as Julio. Before Gonzalo Jr. came a daughter named Edjuly and after him was María Alexandra; they were then aged 13 and 7. There was also a baby of seven months named Jesús Enrique. “When Gonzalo died,” said Hercilia in the late 1980s, “there were many problems because we had no insurance.” As a result, the Gonzalo Márquez Foundation was established with the goal of helping Venezuela’s professional ballplayers, retirees to begin with. Hercilia dedicated much time to this venture at first, but she lived 25 miles from Caracas and could not continue. After the foundation’s president, Gustavo “Gus” Gil, moved to the US, the need arose for someone to take charge.37 Unfortunately, that did not happen, and the foundation ceased to operate.

In January 1985, shortly after Márquez’s death, the Caracas Leones retired his uniform number 6 in tribute. The pregame ceremony was solemn and moving; in the ensuing game, Andrés Galarraga marked the occasion by hitting a home run.38

Estadio Gonzalo Márquez in Carúpano is named for the local hero, who entered the Hall of Fame of Venezuelan Sports on May 29, 2002.39 He also became a member of the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame on November 17, 2008. His widow accepted the honor.40 Yet another fitting way to remember Gonzalo Márquez is by the title of respect that he earned in Venezuela. El Caballero del Béisbol — The Gentleman of Baseball — was known for his fine character on and off the field.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to the family of Gonzalo Márquez for their support. Continued thanks to Marcos Grunfeld in Venezuela for his help with Caribbean Series statistics. Thanks also to Danny García.

This biography was originally published in October 2013. It was most recently updated on March 1, 2021.

Sources

Books

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City:

Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V.: 11th edition, 2011).

Internet resources

baseball-reference.com

retrosheet.org

purapelota.com (Venezuelan statistics)

comc.com (online sports card market with repository of images)

Notes

1 Major leagues (regular season and postseason), Venezuelan winter league (regular season and postseason), Mexican summer league, Inter-American League, and Caribbean Series.

2 Gonzalo Márquez birth certificate, courtesy of the Márquez family; Ron Bergman, “What Will A’s Do With Pinch-Hitting Hero?,” The Sporting News, November 18, 1972, 41.

3 Alfonso L. Tusa C., “Un gran momento de Gonzalo Márquez,” Magallaneando blog, October 9, 2012 (magallanenando.blogspot.com/2012/10/un-gran-momento-de-gonzalo-marquez.html).

4 Carlos Figueroa, “80 años del natalicio de Gonzalo Márquez,” Últimas Noticias (Caracas, Venezuela), March 31, 2020. Bill Bryson, “Oaks Unleash Hurricane in Batter’s Box: Márquez,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1970, 27.

5 Eduardo Moncada, “Big Hassle Erupts as Sharks Demand a Ban on Cardenal,” The Sporting News, December 11, 1965, 27.

6 Eduardo Moncada, “Caracas Fires Harrelson, Played Golf as Rest Cure,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1966, 27.

7 The Sporting News, June 15, 1968, 39.

8 2010 interview with Jesús Méndez on the now-defunct Venezuelan website Batazos.com; glimpses of the story are still visible through Google search results.

9 Bryson, “Oaks Unleash Hurricane in Batter’s Box: Márquez.”

10 Bryson, “Oaks Unleash Hurricane in Batter’s Box: Márquez.”

11 Ron Bergman, “Blue Pitch for Long Green Leaves Finley Seeing Red,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1972, 32. Pete Swanson, “Big Sticks Could Give Added Boost to A.A. Gate,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1972.

12 “Williams wants pinch hitters,” United Press International, October 8, 1972.

13 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Late 3M Rally Boosts Athletics’ Series Stock,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1972, 7.

14 Clif Keane, “A’s sting Tigers, 3-2,” Boston Globe, October 8, 1972.

15 “Williams wants pinch hitters.”

16 “Williams wants pinch hitters.”

17 Hal Bock, “A’s nip Tigers in 11th; rookie settles it,” Associated Press, October 8, 1972.

18 Pete Bennett, “Relievers Didn’t Do Job, says Disappointed Dick,” Associated Press, October 12, 1972.

19 Milt Dunnell, “One Big Regret,” Toronto Star, February 16, 1973, 15.

20 “No geniuses among managers —Sparky,” Associated Press, October 12, 1975.

21 Ron Bergman, “Will DH Slash Hill Staffs? Not Finley’s 10-Man Corps,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1973, 37.

22 Ron Bergman, “New Rule, New Role: Johnson Enjoying Both,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1973, 3.

23 “People in Sports,” New York Times, DATE, 1973.

24 Ron Bergman, “Series Still the Big Thing to 20-Win Holtzman,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1973, 8.

25 “Richard Dozer, “Cubs win,” Chicago Tribune, September 22, 1973, A1.

26 Andrés Galarraga with Humberto Acosta, Andrés Galarraga: Una Historia que Contar (Caracas, Venezuela: Los Libros de El Nacional, 2009). Galarraga said he enjoyed the Caribbean Series experience even though he didn’t get a single turn at bat.

27 E-mail from Danny García to Rory Costello, September 14, 2013.

28 Billy Russo, “Siempre tuve el sueño de ser pelotero,” MLB.com, February 2, 2010 (mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20100201&content_id=8007352&vkey=ozzie_guillen&c_id=mia).

29 “Gonzalo Marquez, scout for Los Angeles Dodgers,” Associated Press, December 22, 1984.

30 Rosa Alma John, Los Leones del Caracas (Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Cejota, 1982), 205.

31 Other sources show that Fred Ferreira signed Azócar for the Yankees. See “Profiles of Coaches, Players on A-C Yanks 1988 Roster,” Schenectady Gazette, April 6, 1988, 34.

32 “Falleció el ex-pelotero Oscar Azócar,” Meridiano.com.ve, June 17, 2010.

33 Peter Hadekel, “The Big Cat,” Montreal Gazette, May 31, 1986, G-4.

34 Bruce Markusen, “Remembering Gonzalo Márquez,” Oaklandfans.com, May 6, 2004 (oaklandfans.com/columns/markusen/markusen174.html).

35 Hadekel, “The Big Cat.”

36 Richard Justice, “Andres Galarraga Called Best in National League,” Washington Post, July 3, 1988.

37 Carlos Lares Cárdenas, Venezolanos en las Grandes Ligas. Sus Vidas y Hazañas 1939-1989 (Caracas, Venezuela: Nacho, 1990).

38 Alexis Salas H., Los Eternos Rivales (Caracas, Venezuela: Seguros Caracas, 1988), 301. Galarraga, Andrés Galarraga: Una Historia que Contar. The other ten numbers retired by the Leones belonged to Pompeyo Davalillo, Víc Davalillo, César Tovar, Tony Armas, Baudilio Díaz, Urbano Lugo, Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel, Omar Vizquel, and Andrés Galarraga.

39 “Siete figuras del deporte nacional ingresarán al Salón de la Fama,” Notitarde (Valencia, Venezuela), May 28, 2002.

40 “Exaltados nuevos miembros al Salón de la Fama del Béisbol Venezolano,” Solodeportes.com, November 18, 2008 (solodeportes.com.ve/2008/11/1238/exaltados-nuevos-miembros-al-salon-de-la-fama-del-beisbol-venezolano/).

Full Name

Gonzalo Enrique Márquez Moya

Born

March 31, 1940 at Carupano, Sucre (Venezuela)

Died

December 20, 1984 at Cagua, Aragua (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.