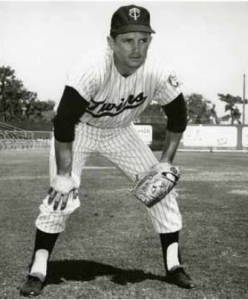

Bernie Allen

Although the Purdue University Boilermakers football team ended the 1960 season with a mediocre 4-4-1 record (despite which they still finished the season ranked 19th in the Associated Press poll), they nevertheless snared two signature victories. On October 15 Purdue hosted then-unbeaten and third-ranked Ohio State University and upset the Buckeyes, 24-21. The following month they scored an even bigger upset when they traveled to Minnesota and upended the number one-ranked Gophers, 23-14.

Although the Purdue University Boilermakers football team ended the 1960 season with a mediocre 4-4-1 record (despite which they still finished the season ranked 19th in the Associated Press poll), they nevertheless snared two signature victories. On October 15 Purdue hosted then-unbeaten and third-ranked Ohio State University and upset the Buckeyes, 24-21. The following month they scored an even bigger upset when they traveled to Minnesota and upended the number one-ranked Gophers, 23-14.

As Purdue’s starting quarterback, senior Bernie Allen played a prominent role in both wins. Many years later, long after his professional baseball career was ended, Allen recalled, “What I am most proud of in regards to my football career at Purdue was that I never lost to Notre Dame or Indiana. Those two in-state schools were, and still are, big rivals for Purdue.”1 In particular, one game he most enjoyed “was when I kicked a field goal to beat Ohio State, 24-21. Woody Hayes [the legendary Ohio State coach] had said I was too small to play football in the Big Ten, so I was happy to prove him wrong face to face.”2 In the end, whether or not Allen was too small to play football never really mattered, because all he ever wanted to be was a baseball player.

Born on April 16, 1939, in East Liverpool, Ohio, Bernard Keith Allen was one of the greatest all-around athletes in the history of East Liverpool High School. A star in baseball, football, and basketball (in which he was named a High School All-American), Allen was inducted into the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame as a member of the inaugural class of 1982. One of five children born to Thurman and Fern Allen, Bernie no doubt emulated the athletic prowess of his father, who played baseball and was an avid golfer. Thurm, as he was known, spent 47 years employed by the Smith and Phillips Furniture Company, from which he retired in 1981 as vice president and general manager.

When Bernie graduated from high school in 1957, his athletic skills were in high demand at the collegiate level, but he had also drawn notice in major-league baseball. Ultimately, Purdue proved largely an afterthought. “Previously,” Allen told Sports Collectors Digest, “I had visited Ohio State and met with coach Woody Hayes [following which he received Hayes’s rebuff that he was too small to play Big Ten football]. I was only 6-foot, 180 pounds. I was planning on going to Colgate, but the August after I graduated from high school, Billy Elias, who was a Purdue assistant football coach, came down and watched me play in a summer baseball tournament. He convinced me to [at] least visit the campus. My mom, dad, and I visited Purdue and we really liked the campus.

“I made it clear that baseball was my number-one sport. The scholarship was for football, as there weren’t many full baseball scholarships in those days. I was intent upon playing pro baseball, but I wanted to get an education first.” Additionally, “The Yankees were very interested in me at that time.” Nonetheless, Allen enrolled at Purdue University.

At the time, freshmen didn’t play varsity athletics, so Allen became the sixth of nine quarterbacks on the freshman team’s depth chart, a circumstance that worked in his favor. “The freshman team was actually cannon fodder for the varsity,” he recalled. “The quarterbacks above me … kept getting hurt as they went up against the varsity. … By the time I got to play against them late in the year, I was getting comfortable with the system. I completed some passes against the varsity and caught the attention of the coaching staff [which included future New York Yankees owner, and Allen’s future boss, George Steinbrenner, whom Allen recalled as ‘an excellent recruiter’]. At the end of the season, the freshman team had a big intrasquad game, and I was named MVP of the game.” The following season, Allen joined the varsity.

In that first varsity season, Allen was a starting defensive back on the best defensive team in the country; during the season’s last several games, he also saw action at quarterback. Yet Allen also was a standout on the varsity baseball team, for whom he was named the season’s MVP, and that drew the consternation of football coach Jack Mollenkopf, who, Allen said, “kept telling me I wouldn’t even make the baseball team. He wanted me to give up baseball and concentrate on football.” Thus began yearly battles with the pugnacious football coach.

As his junior season got under way in 1959, Allen was slated to be the second-string quarterback behind Ross Fichtner, who went on to become a successful defensive back with the Cleveland Browns. While Allen continued to pursue his dream of playing major-league baseball, Coach Mollenkopf demanded his presence at football practice. “In the spring of my junior year,” Allen recalled, “I agreed to leave baseball practice early to go to football practice. Mollenkopf claimed we were supposedly putting in a new offense. After a couple of days,” however, “I realized that the offense wasn’t new, only the terminology.” Nevertheless, Mollenkopf’s needling paid dividends to the football program, for in the season’s second game Fichtner broke his collarbone, and Allen assumed the starting position. He remained the starter for the remainder of that season and all of the next.

By his senior season, Allen was firmly entrenched as Purdue’s starting quarterback. His availability for that role, however, wasn’t a certainty. “I almost packed it in after my junior year,” Allen reflected, “as I wanted to put my brother through college.” For the final time, Mollenkopf railed against Allen’s lack of commitment to football; but to pursue his passion, Allen again weathered Mollenkopf’s wrath, in exchange for a singular moment.

“I missed the first two days of football practice as I was playing [baseball] in the NABC tournament in Wichita.” There, “I got to face Satchel Paige. … Admittedly, he was at the end of the line, but still, it was Satchel Paige.”

Returning to Purdue, Allen faced his tormentor. “My punishment for missing two days of practice was that Mollenkopf was only going to let me play defense in our first game of the season, against UCLA. It was real hot, so I didn’t mind only getting to play defense. We were down eight points when we got the ball back for the final time, with about a minute to go in the game. As I came off the field with the defense, Mollenkopf told me to get back in there and throw the ball. … We ended up scoring a touchdown. We went for two and scored. It ended up 27-27. As I came off the field, Mollenkopf said, ‘You’ll start next week versus Notre Dame.’ I remarked, ‘Don’t do me any favors.’ The next week, we went out and beat Notre Dame 51-19.”

That season Allen was named the football team’s MVP. In an era of run-dominated football, he completed 59 percent of his passes, threw for 765 yards, and tossed five touchdowns. Allen’s 54 points led the team in scoring, as he rushed for four touchdowns and kicked 21 points after touchdown and three field goals. He also punted 38 times for a 34.9-yard average. In his three varsity football seasons, Allen completed 49 percent of his passes for 1,200 yards, threw for 10 touchdowns, and tossed 11 interceptions.

With his collegiate football career over, there was never a question of playing the sport professionally. “I never had any desire to play football after college,” Allen later recalled. “In fact, I played football only to get an education. I never really enjoyed it.” And of Allen’s availability for National Football League teams, he said, “There never was any doubt in my mind at that time. I received many phone calls from pro grid teams, but I told them not to waste a draft pick because I wanted to play baseball.”3

The turning point in Allen’s future professional baseball career came the afternoon of the football team’s upset victory over the Minnesota Gophers. “After the game at Minnesota, as we made our way out of the locker room and onto the bus, the Minnesota fans came up and congratulated us on how well we had played. I remembered those gracious fans a few months later when I was trying to decide whom to sign with. It came down to the Twins and the New York Mets. I took half as much money to sign with the Twins. … The Mets weren’t really even in existence at that point. They were just out signing players. The Tigers had wanted to sign me as a catcher, but I knew they had just signed Bill Freehan, whom I had played against in college [Freehan attended the University of Michigan]. I knew how good of a catcher he was.” So Allen signed with the Minnesota Twins, and began what became a 10-year career in the major leagues. (Allen, who batted .360 in three varsity seasons at Purdue, was signed by Twins scout Dick Wiencek.)

Allen played just 80 minor-league games before reaching the majors. After signing in 1961, he spent two weeks with the Twins before they sent him to the Charlotte (North Carolina) Hornets, in the Class A South Atlantic League, where he finished the season. Over that span, Allen was mediocre at the plate, .241/.324/.320, but proved a major-league-caliber fielder. The following spring, Allen made the Twins roster, spent the entire season with the team, and took over as the starting second baseman. With the exception of 41 Triple-A games four years later while he was recovering from an injury, Allen never again played in the minor leagues.

On Opening Day 1962, Allen took his place as the Twins’ starting second baseman. He replaced one of baseball’s most enigmatic personalities. The previous fall, Billy Martin, in his lone season as a player with the Twins, had ended his 11-year playing career. Outplayed by Allen during spring training of ’62, Martin was subsequently released by Minnesota. Allen always remained grateful to Martin for the veteran’s mentoring, in spite of their competition.

“Even though Billy knew that I was trying to replace him, he taught me to truly play second base,” Allen later explained. “Billy emphasized that it was important for the older players to help the younger players learn how to be major leaguers. … Billy also taught me to be serious on the field. It’s okay to have fun off the field, but you have to play like a pro on the field. It’s a business.”

Indeed, Allen never forgot Martin’s advice. Years later, after he’d been traded to the Washington Senators, Allen developed “my own little entourage – Toby Harrah, Jeff Burroughs, Tom Grieve, and Jim Mason. They followed me around all season. I was glad to help them.”

(After he retired, Allen often accepted invitations to play in Martin’s golf tournament. “[Martin] would take me around the room, telling people that I was the player who forced him to retire as a player. That made me feel great, but actually it was Father Time who made Billy retire.”)

On the field Allen never enjoyed a finer season than his rookie year of 1962. In fact, he rarely again even approached the offensive numbers he posted that season. With a slash line of .269/.338/.403, Allen, who typically batted seventh, ahead of shortstop Zoilo Versalles, set career highs in almost every offensive category, including impressive power totals of 27 doubles, 7 triples, 12 home runs, and 64 RBIs. Defensively, too, Allen was stellar. Only once after that season did he produce a better fielding percentage over a full season than that year’s .983, the fifth best average in the league among second basemen; and in 158 games he turned the league’s third highest number of double plays. Allen received one first-place vote in the Rookie of the Year balloting (the Yankees’ Tom Tresh won the award), and was named to the Topps All-Rookie team. It was a heady season; yet it marked the pinnacle of Allen’s career.

If Allen’s rookie season announced him as one of baseball’s rising stars, the next two years frustratingly quieted any acclaim. In 1963, as the Twins, under manager Sam Mele, looked to improve on 91 wins and a second-place finish, Allen inexplicably got off to a dreadful start. After an 0-for-4 performance on June 21 that left his batting average at just .197, Allen was temporarily benched in favor of Johnny Goryl, before recovering his stroke to finish the season with a .240 average. Years later, Allen blamed his poor performance that season on a change in stances, explaining, “I was a spray hitter that first season. The following spring they told me I couldn’t hit with my stance, so they changed me to become a pull hitter. I figured they knew more than I did, but maybe they didn’t.”4 Allen’s defense suffered too, as his fielding percentage dropped to .976. That year, he started only 110 games. (Ironically, in April 1964, Mele stated, “I want [Allen] to learn to become more of a punch hitter, something like Nellie Fox. He [Allen] hit well to left field two years ago. When Bernie tries to pull the ball, he has trouble.”5)

Things got even worse in 1964, although for a moment Allen seemed to regain his footing. For all intents and purposes, that season effectively marked the end of his tenure as a full-time player. It began in the spring, as Allen engaged with Goryl in a hard-fought battle to retain the second-base job. After working extremely hard at all facets of his game, Allen won the Opening Day start, yet began the season with just one hit in his first nine at-bats, before he exploded with four hits in his next seven, including a two-homer game on April 18 at Washington. By the next afternoon his average stood at .313, and it appeared that his 1963 season had been an aberration.

“We moved Bernie up closer to the plate so he would be more aggressive with the bat,” Mele remarked about coaching the left-handed hitter. “He had to swing hard or get jammed. It worked. He’s been swinging well ever since.”6

Likewise, Allen’s defense returned to his rookie-year heights, as Twins owner Calvin Griffith attested. “Bernie’s looking sharp in the field,” Griffith said, “much like he did two years ago. He has made several good plays going far to his left. I think he’s improving his range.”7

As with his hitting, coaches offered Allen much advice on ways to improve his defense. “One coach,” he said, “had me standing on my toes with my arms hanging down low. I almost fall on my face when I try that. When I was a quarterback, I used to get a good start moving laterally. But I was bent over just enough to get my hands under center.

“That’s the way I like it in baseball – bend over just enough to put my hands on my knees. Then I get lower as I move left or right. When I start too low, I usually stand up and then move, which slows me down.”8

After his impressive start, Allen tailed off significantly; his batting average bottomed out at .149 on May 13. By June 13, however, Allen had raised it to .220, and his fielding had regained its efficiency. Then it all fell apart on the infield dirt in Washington. On the 13th the Twins led, 2-1, in the bottom of the fifth. Leading off for the Senators, Don Zimmer drew a walk, and left fielder Chuck Hinton came to the plate. As Allen recalled, “It was a hit-and-run play. Chuck Hinton hit the ball to Zoilo Versalles at short. The grass was tall, so the ball was slow in getting to him. Zoilo made a soft toss which I had to wait on. …9 The runner and ball got to me at the same time, Don Zimmer giving me a cross body check that tore up the ligaments in my left knee.”10

It was a devastating injury, the kind that in those days typically ended careers. After missing almost two months, Allen returned on August 4, played 10 games, then missed a week before returning on August 21. With a batting average of just .214, he saw his season end prematurely on September 1. Allen wasn’t operated on until October, and then only because he sought medical advice on his own from the Minnesota Vikings’ orthopedic surgeon, who diagnosed tears in both medial collateral and anterior cruciate ligaments.

“By the time they operated,” Allen recalled, “the ligaments had shriveled up.”

Surgeons took part of the hamstring from Allen’s left leg and used it on his knee. “The doctor said I had a 50-50 chance of ever being able to play any type of sport again, and zero percent chance of ever playing baseball. … The average career at that time was four years. You had to play five years back then to get a pension. The rehab was very painful. I had to wear an iron boot everywhere I went, to build up the strength in my leg.”

Allen was disappointed in the team’s reaction to his injury. “What really upset me was that I didn’t receive a card or a call from anyone in the Twins front office. Then, to top it off, they wanted to cut my salary from $12,000 to $10,000 in 1965.”

Allen would never again be the same player he was as a rookie.

As luck would have it, the Twins went to the World Series in 1965. In the aftermath of his injury, Allen missed the chance to participate. Still rehabbing his knee, he was on the disabled list from the beginning of the season until June 4. He returned on June 22 and played 19 games, but was eventually sent to Denver in the Pacific Coast League.

“They had told me I would be called up before the rosters were expanded in September,” Allen said. “That way I would be eligible for the World Series. Right before I was to go back up,” though, “I dove for a ball and broke my thumb. That ended my year right then.”

Much to Allen’s disappointment, he failed to receive a World Series ring. “I got seven-eighths of a share [of the Series winnings], but I didn’t get a ring. That’s what I really wanted. Mudcat Grant, Jim Kaat, and others went to the front office on my behalf. I’ve never forgotten that slight. A few years later, Johnny Klippstein dropped his ring and the diamond broke. That must have been some fine diamond,” he said with sarcasm. As things turned out, Allen’s time in Minnesota was almost through.

Throughout Allen’s time with the Twins, likely motivated by his injury and undoubtedly with a thought to his post-playing career, he displayed an interest in business matters both in and outside the sport. In 1962 infielder Rich Rollins had joined the Twins, and Allen and Rollins forged a friendship; both were from Ohio, shared the same birthday (although born a year apart), were roommates on the road, and had adjoining lockers during home games. Following Allen’s injury, pitching coach Johnny Sain gave him a book called Think and Grow Rich, a treatise on positive thinking written by 83-year-old Dr. Napoleon Hill, who had been teaching his principles since 1908. Allen read the book during a two-week stint in the Army Reserve and asked Rollins to read the book. The two took Dr. Hill’s course and together opened a Napoleon Hill Academy franchise in Minneapolis. A year later, after Allen was traded, they sold the franchise, and then opened an agency in St. Paul, Minnesota, for the Wayne National Life Insurance Company (partly owned by Al Kaline). Although they were then playing for different teams, Rollins handled PR for the firm, while Allen did some selling.11 Theirs was a friendship that lasted beyond their playing days.

The year 1966 was Allen’s final season with the Twins. On December 3, after a season in which he split time at second base with César Tovar, Allen and pitcher Camilo Pascual were traded to the Washington Senators in exchange for reliever Ron Kline. Announcing the trade in its December 17, 1966, edition, The Sporting News reported that “Allen was a play-me-or-trade me malcontent” who had batted just .238, but was playing well until June, when he reinjured his knee. In contrast, Allen later contended, “I got traded for a very simple reason. I was the players’ rep on the Twins. Being a players’ rep in those days was a surefire way of getting yourself traded.”

Having endured a pay cut with Minnesota, to $10,500, Allen was anxious for a pay raise with his new team. “George Selkirk, who was a former Yankee player, was the Washington GM,” Allen remembered. “He and I had a tough time negotiating. We negotiated through the mail.” In the end, Selkirk increased Allen’s salary to $15,000. His teammates quickly voted in Allen as the Senators’ player rep.

Over the next five full seasons with mediocre to poor Senators teams, Allen evolved into the role of a part-time second baseman, splitting time with such players as Bob Saverine, Frank Coggins, and Tim Cullen; he also saw some action at third base. Still able to generate some occasional pop in his bat (in 1969 he produced the second highest home run and RBI totals of his career 9 and 45), Allen’s batting average with the Senators was .237. During his first year with the team, in which he batted a dismal .193, Allen was diagnosed with astigmatism in his right eye, particularly hampering to a left-handed hitter. As a result, Allen tried wearing glasses at the plate, but later remembered, “I could never adjust to wearing glasses, but I found it possible to wear a contact lens in my right eye. My left eye was fine, so I decided to wear only the necessary lens.”12 Ultimately, he added, “the eye didn’t hamper me as much as the knee injury, which still bothers me in cold weather.”13

By his final season in Washington, Allen was being used only sparingly by manager Ted Williams. Although the team had finished 10 games over .500 and in fourth place in the American League East during Williams’s first season, 1969, two years later they had fallen to 63-96 and fifth place. That year Allen started just 24 games at second base, and he later recalled Williams as “the most egotistical man I’ve ever met in my life.”14

“The first year he managed he wasn’t bad at all, but he lost communication with the players last season [in 1971].”15

One day in late July 1971, Williams asked Allen, “How are you?” and Allen responded, “I’d be better if I were playing more;” after that “he never said hello to me the rest of the year. I don’t know what I did to him, but he just refused to play me.”16

“When you have six hits in your last seven times at bat and can’t start against a right-handed pitcher the next day, I don’t know what I’m supposed to think of him.”17

By then Allen knew he was no longer in the Senators’ plans. After the 1971 season the team moved to Texas and became the Rangers, and on December 2, 1971, the Rangers traded Allen to the New York Yankees for two left-handed relievers, Gary Jones and Terry Ley.

Allen was cheered by the move, “chiefly because I had always admired Ralph Houk.”18 Acquired as a backup to second baseman Horace Clarke, Allen initially thought he might be a candidate to play third base, but when the Yankees acquired Rich McKinney, Allen understood what his role would be.

“I never got a chance to talk to Ralph until spring training,” Allen said. “He told me exactly what job he had planned for me, then didn’t deviate. The whole Yankee organization has treated me better than any I’ve ever been with.”19

In all, Allen played 84 games for the Yankees in 1972, splitting time equally between second and third base. In May the Yankees traded their player rep, Jack Aker, to the Cubs, and as with his two previous teams, Allen was elected to replace him.

The next season was Allen’s last. In August the Yankees sold his contract to the Montreal Expos, for whom he played his final 16 games. In November the Expos asked waivers on Allen and gave him his unconditional release, at which point he chose to retire.

“I knew I was going to hang it up at the end of that year,” Allen recalled 25 years later, “even before I was traded. The Expos wanted me to come back, but I knew it was time to call it quits.”

In retirement, Allen became a successful businessman, yet also took an opportunity to keep his ties with the game. An old college classmate owned a sporting-goods store in West Palm Beach, Florida, so Allen relocated with his first wife, Sharon, and four children to become the store manager. Coincidentally, at the same time the Expos had a Class A team in town, the West Palm Beach Expos of the Florida State League. The owner of the store purchased the team when it came up for sale. Jim Fanning, the Expos’ GM, approached Allen and asked his opinion regarding a manager, and after assessing the candidates, Allen suggested Felipe Alou. During the team’s homestands, Allen coached first base and instructed the infielders.

Allen also kept tabs on old friends from his playing days, such as Roy Sievers, with whom Allen often played in golf tournaments, and who stood in as best man at Allen’s wedding to his second wife, also named Sharon.

In 1982 Allen became Midwest representative for the Ferro Corporation, a performance materials company based in the Cleveland suburbs. His territory covered western Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Allen and his second wife (his first marriage ended in 1987) had two sons, four daughters, and seven grandchildren, and lived in Carmel, Indiana.

As of 2015, Allen still resided in Carmel.

Sources

The author attempted to interview Bernie Allen for this biography, but was unsuccessful.

Sincerest appreciation to SABR member Bill Mortell for his research contribution.

Bernie Allen player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame,Cooperstown, New York

NewspaperArchive.com

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Sports Collectors Digest, November 20, 1998. Unless otherwise noted, all of the Allen quotes in this biography are taken from this article.

2 The Sporting News, July 15, 1972. Note: Allen’s field goal came in the third quarter, and put Purdue ahead 17-14. After a subsequent touchdown that put Ohio State ahead, 21-17, Allen led Purdue on a drive that culminated in the game-winning touchdown, after which he kicked the extra point.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 The Sporting News, April 18, 1964.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Sports Collectors Digest, November 20, 1998.

10 The Sporting News, July 15, 1972.

11 The Sporting News, February 4, 1967.

12 The Sporting News, July 15, 1972.

13 Ibid.

14 Unidentified clipping dated March 9, 1972, in Allen’s Hall of Fame file.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 The Sporting News, July 15, 1972.

19 Ibid.

Full Name

Bernard Keith Allen

Born

April 16, 1939 at East Liverpool, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.