San Francisco Giants team ownership history

This article was written by Rob Garratt

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

Editor’s note: This article continues from Part 1, on the New York Giants team ownership from 1883 to 1957.

Stoneham the Younger

The narrative of Giants ownership had changed abruptly and dramatically on January 6, 1936, when Charles A. Stoneham died of symptoms associated with Bright’s disease. The franchise immediately passed into the hands of Stoneham’s son, Horace Charles Stoneham, who at the age of 32 became the youngest owner in National League history.1 The elder Stoneham had prepared his son well for the responsibility. Young Horace joined the Giants organization in 1924, serving for a number of years as the ticketing manager, facilities director, and travel coordinator. In 1932, with an eye to the future, his father promoted him to the front office to learn the operations of the club, working under John McGraw and Bill Terry. When the elder Stoneham passed, Horace not only inherited the ballclub, but was positioned to handle administrative duties. In his first two full years as owner, the Giants won the NL pennant, but lost to the crosstown Yankees in the World Series.

The narrative of Giants ownership had changed abruptly and dramatically on January 6, 1936, when Charles A. Stoneham died of symptoms associated with Bright’s disease. The franchise immediately passed into the hands of Stoneham’s son, Horace Charles Stoneham, who at the age of 32 became the youngest owner in National League history.1 The elder Stoneham had prepared his son well for the responsibility. Young Horace joined the Giants organization in 1924, serving for a number of years as the ticketing manager, facilities director, and travel coordinator. In 1932, with an eye to the future, his father promoted him to the front office to learn the operations of the club, working under John McGraw and Bill Terry. When the elder Stoneham passed, Horace not only inherited the ballclub, but was positioned to handle administrative duties. In his first two full years as owner, the Giants won the NL pennant, but lost to the crosstown Yankees in the World Series.

With this early success, Stoneham saw little reason to intervene in the day-to-day operations of the club, trusting in his manager, Terry, to make the personnel decisions. Terry did the evaluation, the trading and signing of players and the proof, as they say, was in the pudding. Stoneham’s main task during this period was adjusting to the culture of baseball as an owner and learning the intricacies of payroll and player development.

Horace was not completely inactive, however. In the first few months after his father’s death, he began a shakeup of the front office, replacing club secretary Jim Tierney, his father’s close associate but a man whom the younger Stoneham never trusted, with longtime Giant loyalist Eddie Brannick. Brannick had joined the Giants in 1906 as a clubhouse boy, served as traveling secretary for McGraw, and remained in that capacity under Charles Stoneham. His loyalty to the organization was not lost on the younger Stoneham. Indeed, loyalty would prove to be an essential quality for Horace Stoneham. Throughout his 40 years as owner of the Giants, he would reward and retain players, executives, and club officials because of their dedication and commitment to the organization.

As the new decade of the 1940s began, Stoneham grew more confident of his role as owner and more secure in his baseball judgment. He also began to plan for the future of his ballclub. Sensing the decline of the Giants performance when measured against the two other New York teams — the Yankees were enjoying a phenomenal run that would take them into the next decade as the most prominent team in the game, and the Dodgers were dramatically improving; after they won the 1941 NL pennant, the Giants would be in most fans’ minds the third team in the city.2

By the summer of 1955, Stoneham sensed something far more ominous in the Giants’ third-place finish and dwindling gate receipts. He began to realize that his ballpark, the aging Polo Grounds, was a great liability, dimming opportunities for his beloved club in New York City. Giants attendance for the 1955 season would total 824,000, down considerably from the 1,115,000 of the previous year’s championship season. Although Stoneham could seek some solace in baseball’s overall numbers — the mid-1950s attendance throughout baseball was down almost 40 percent from an all-time postwar high in 1948 — he could not deny the blunt fact that his New York Giants suffered the greatest slide among National League clubs despite playing in its largest market. In 1955 only the small-market teams of Pittsburgh and Cincinnati drew fewer fans.3

Moreover, Stoneham could no longer ignore the fact that his attendance problems went beyond his team’s wins and losses. He understood that where the Giants played had as much to do with the club’s present circumstances as how they played. Despite its tradition and history, the Polo Grounds, both as a facility and a location, was past its prime.4 A dilapidated stadium situated in what many considered a deteriorating neighborhood, the Polo Grounds would require major renovations to bring it up to the standards of the day. One of the oldest parks in baseball, it predated even Ebbets Field and was showing its age in seating, fan facilities, façade, and pedestrian traffic, especially the egress. After a game the crowd had to pour onto the playing field to exit through the center-field gates.5 Repairs and remodeling would be costly if Stoneham wanted to improve fan comfort, and these expenses would cut into his already dwindling bottom line.

Repairs and renovation of the ballpark, however necessary, were only part of Stoneham’s stadium woes. Even more troubling was the changing nature of the neighborhood surrounding the park. In the late 1940s, a number of housing projects were planned for Harlem, the first of which was Colonial Park, which opened in 1950 opposite the Polo Grounds. By the mid-1950s, middle-class white fans came to perceive that the area around the park was becoming dangerous and a trip to the ballpark seemed like a risky affair.6 Stoneham believed fans might feel safer if they could drive to the ballpark. Though he had spent the majority of his life in Manhattan with its extensive and reliable transportation system, Stoneham sensed that future American life would be shaped and determined by the automobile. He watched the boom in postwar automobile production and sales, due in large part to meet the needs of young families leaving the cities for the suburbs.

At the end of the 1955 season, with all of these concerns troubling his daily operation of the team, Stoneham began to weigh the future of Giants baseball in New York. He entertained a number of options. Recalling that the Giants were landlords to the Yankees in the early years of his father’s ownership, he pondered becoming a tenant of the Yankees.

Stoneham also had another card up his sleeve in the form of an idea for a new ballpark to be shared by both the Giants and the Yankees. The idea was more of a pipedream, doomed from the start since it required public financing that the city would not provide and cooperation from the Yankees, who were happy in their present location. During the late spring and summer of 1956, he also entertained what was surely the most far-fetched and elaborate scheme for a ballpark, even one intended for the Giants.7 The notion, put forth by Manhattan city politician Hulan Jack, was to build a 100,000-capacity stadium to rise above the New York Central Railroad’s West Side Yard that would also provide parking for about 20,000 cars. Jack argued that he had planners and investors to advance the project and thereby keep the Giants in Manhattan. Stoneham is on record as showing interest, meeting with Jack and his committee, but expressing his characteristic caution.8 As the cost estimates for the project continued to rise, the city’s enthusiasm fell and the railway company remained distant; plans for the so-called “stadium on stilts” faded away.9

These suggestions about Stoneham’s solutions to the Giants’ ballpark woes were always devoid of particulars and served as diversionary tactics, allowing him to play a waiting game and consider his alternatives. Stoneham gave no public indication of real concern, and certainly none of panic; it was business as usual for the New York Giants. He simply behaved publicly as he always had done, generous to a fault, providing hospitality for sportswriters, and standing rounds at Toots Shor’s famous Manhattan saloon that catered to New York sports celebrities, bantering hopefully about his ballclub. With rumors flying about the Giants moving out of the Polo Grounds, and even out of the city, Stoneham would calmly dismiss everything as speculation, saying he had a lease with the Coogan family and he planned to be in New York for “years to come.”10

At the same time Stoneham insisted that the Giants would stay put in New York, and were committed long-term to the Polo Grounds, he began entertaining a radical idea, something that just two years before would have been unthinkable. He gave serious consideration to the idea of moving the team out of New York. His first thoughts were to plan simply, minimize complications, keep costs manageable, and hold his cards close to his vest. By early 1956, he knew he could not remain much longer in his present location. Minneapolis, home to his Triple-A farm team, the Millers, and a major Midwest city, seemed a very attractive option.11 As a Giants franchise, the Minneapolis Millers gave Stoneham rights to the city’s territory.

But as he contemplated his move to the Midwest, Stoneham did so in his customary wary and discreet manner. Making up his mind to move and selecting a date to do so were two very different undertakings for Stoneham. With his lease with the Coogan family for the Polo Grounds securely in hand, he could afford to sit back and let the action come to him. Whenever he was asked about the Giants’ future, he responded as the loyal son he was, suggesting that things might work out somehow and the Giants could be in New York for a long time to come. Even with his awareness of the problems with the Polo Grounds, Stoneham was not quite ready to establish a deadline, or to go public with any decision. Admitting to Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley in a confidential, informal conversation in March 1957 that he had made up his mind to move to Minneapolis, he did not feel an overwhelming urge for any public pronouncement just yet.12 His waiting game would prove momentous. In the late spring of that year, he would be lobbied by three different parties, each of them urging him to expand his horizons westward another 2,000 miles to consider San Francisco and the lucrative California market.

As Stoneham considered his options, the City of San Francisco began its plans for major-league baseball. In 1954 its voters passed a bond measure to build a new stadium and in 1956 newly elected Mayor George Christopher formed an official city task force to attract a major league team. By mid-1957, in conjunction with the mayor’s office in Los Angeles, Christopher and his cohorts began a push to bring big-league baseball to California. Knowing that Los Angeles was courting the Brooklyn Dodgers and their owner Walter O’Malley, Christopher began to consider attracting the other New York National League team, the Giants. In mid-May of 1957, after some encouragement from LA Mayor Norris Poulson and O’Malley, Christopher approached Stoneham with an offer of a new stadium with ample parking and the promise of an enthusiastic fan base waiting for big-league baseball. Weighing his options over the summer, Stoneham decided to forsake Minneapolis in favor of what he thought was a better market with more economic advantages. In August, once he had received an official letter of invitation from the City of San Francisco, Stoneham agreed to move to California for the 1958 season.13

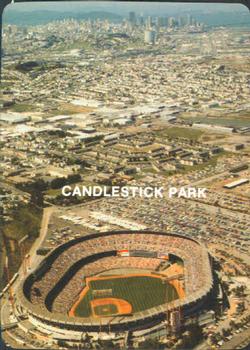

The Giants arrived in San Francisco to great fanfare in April 1958 and for the next 10 years14 played great baseball to enthusiastic crowds. Stoneham profited from the move and was happy in his new location, especially when he moved into his new facilities at Candlestick Park, which seated over 40,000 fans and had parking for over 10,000 vehicles. A unit of stock in the National Exhibition Company (the Giants’ holding company) sold for $125 in 1957, prior to the move out west; in 1964, that same unit sold for $725.

A foggy Candlestick Park, circa 1965. (Photo courtesy of Dave Glass via Flickr.com. Used under Creative Commons 2.0 license.)

Stoneham’s new home turned out to be a far cry from what Vice President Richard Nixon claimed was “the finest ballpark in America” when it opened in 1960.15 Indeed, the ballpark would become something of an albatross for the Giants organization for years to come, with its bad weather, its remote location, and its soulless character. It was trouble from the very beginning, even during its planning and construction, when the city rushed to complete the project. It made questionable land deals with the landowner, Charles Harney, who would also become the builder of the ballpark. Harney lost considerable enthusiasm for the project after the city decided to call the ballpark Candlestick Park, after its location on San Francisco Bay’s Candlestick Point, rather than the Harney Stadium he expected. The completion of the project, in time for the 1960 season, was fraught with rancor and disagreement between builder, architect, and the city, causing various amenities to be cut back or eliminated entirely. Nonetheless, the Giants open to good crowds and played competitive baseball for the first 10 years there, despite the adverse conditions.16

In 1968 things began to change, however, marking the beginning of the end for the Stoneham years in San Francisco. Ominous circumstances were converging, any one of which, taken on its own, might have been manageable; together they were overwhelming, especially for an old-fashioned owner like Stoneham, whose business proclivities and personal bearing were not best matched with crises. Pressure that began with one event in the winter of 1967 would continue to build with others over the next few years and lead to Stoneham’s undoing, forcing an unthinkable decision: to sever a lifelong connection with his beloved baseball club.

The most significant of these events, one that would have disastrous results for Stoneham’s Giants, came in the guise of baseball’s progress: the relocation of the Kansas City Athletics to Oakland for the 1968 season.17 Maverick owner Charles O. Finley had been itching to get out of the Midwest since he bought the team. He had mediocre attendance and a terrible television contract.18 He coveted Northern California and the Bay Area as a prime location after watching the Giants’ success there. The American League felt the same way, having been caught off-guard by the National League’s appropriation of the California market in 1958 when the Giants and the Dodgers moved west. The junior circuit moved into Southern California in 1961 with the expansion Los Angeles Angels and saw Northern California as a good location for another team. Finley was granted permission to move to Oakland at the American League fall owners’ meeting on October 18, 1967, when they also authorized expansion to Seattle and Kansas City no later than 1971. The latter approval by the owners was in part to mollify angry Kansas City folks who were threatening litigation in response to Finley’s exodus.19

The A’s arrived in California with great fanfare in the winter of 1967. Finley greeted a welcoming group of 400 reporters and dignitaries at the airport, promising a long and successful stay in the Bay Area. Sportswriters in San Francisco appeared impervious to any downside for their home team in Finley’s move and, adopting a “the more, the merrier” attitude, extended a warm welcome to the A’s.20 Not so Horace Stoneham, who felt immediately threatened. His remarks stood in sharp contrast to all those excited about a new baseball team in the Bay Area and would prove remarkably prescient for decades to come. “Certainly the move will hurt us. It is simply a question of how much and if both of us can survive. I don’t think the area at the present time will take care of us both as much as (the Athletics) think it will.”21 Taking a more politic and diplomatic stand, Chub Feeney, Giants’ vice president and Stoneham’s nephew, said he welcomed the A’s move and hoped it would work out for everyone, including the Giants.22 Like many in the city, Feeney thought it was too early to pass judgment.

It didn’t take long for the Giants to feel the pinch of the A’s presence across the bay. In 1968, the A’s first year in Oakland, the Giants drew 837,220, down over 405,000 from the previous year. This pattern would persist over the next seven years, Stoneham’s remaining time with the club. Only once after the A’s moved to Oakland — in the playoff year 1971, when the Giants won the National League West title — would Stoneham’s team draw over 1 million fans to Candlestick. In 1974, attendance fell to an abysmal 519,987.23 Only twice before — in 1932 and in the war year 1943 both at the Polo Grounds — did the Giants draw fewer home fans.24 Faced with this new reality, Stoneham was uncharacteristically blunt in his response. “Finley, the A’s and the whole American League are partners in villainy.”25 Sharing the Bay Area market with another major-league ballclub was proving disastrous to the Giants’ ability to maintain financial health.

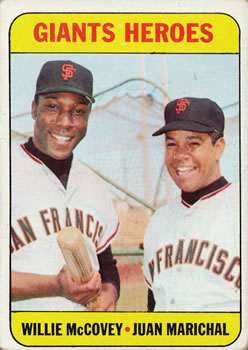

In addition to the A’s, Stoneham sensed yet another looming problem that would cause him further anxiety: His team was aging, especially his best players. Moreover, the Giants’ finances no longer resembled those of the profitable early years in San Francisco. Simply put, Stoneham was running out of money. The major leagues’ days of television contracts, merchandising, and playoff revenue-sharing lay in the future. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the gate was still the primary source of income for ballclubs, and since 1968 the Giants had been drawing poorly. As he looked to a new decade of shrinking revenue, Stoneham had to cut his costs, which made stripping the team of big-name and high-salaried players a practical, however painful, necessity. Orlando Cepeda left in 1966 before the club’s fiscal woes were apparent, easing payroll pressure. Cy Young Award winner Mike McCormick was traded in 1970.26 Gaylord Perry was dealt to Cleveland after the 1971 season (where he was a Cy Young Award winner the next year), and shortstop Hal Lanier was sold to the Yankees for cash.27 All-Star catcher Dick Dietz was traded to the Dodgers in 1971.28 Willie McCovey was sent to San Diego in the fall of 1973 and Juan Marichal was sold to the Boston Red Sox that December. Dave Kingman, who arrived in September of 1971 to be a new Giants power hitter, was sold to the Mets after the 1974 season.29

In addition to the A’s, Stoneham sensed yet another looming problem that would cause him further anxiety: His team was aging, especially his best players. Moreover, the Giants’ finances no longer resembled those of the profitable early years in San Francisco. Simply put, Stoneham was running out of money. The major leagues’ days of television contracts, merchandising, and playoff revenue-sharing lay in the future. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the gate was still the primary source of income for ballclubs, and since 1968 the Giants had been drawing poorly. As he looked to a new decade of shrinking revenue, Stoneham had to cut his costs, which made stripping the team of big-name and high-salaried players a practical, however painful, necessity. Orlando Cepeda left in 1966 before the club’s fiscal woes were apparent, easing payroll pressure. Cy Young Award winner Mike McCormick was traded in 1970.26 Gaylord Perry was dealt to Cleveland after the 1971 season (where he was a Cy Young Award winner the next year), and shortstop Hal Lanier was sold to the Yankees for cash.27 All-Star catcher Dick Dietz was traded to the Dodgers in 1971.28 Willie McCovey was sent to San Diego in the fall of 1973 and Juan Marichal was sold to the Boston Red Sox that December. Dave Kingman, who arrived in September of 1971 to be a new Giants power hitter, was sold to the Mets after the 1974 season.29

Shedding the high-price players posed difficult decisions for Stoneham, but no one trade or player sale brought with it the agony Stoneham felt when he realized he would have to part with Willie Mays. The blunt reality came off the bottom line: The Giants could not afford to keep Mays, at least in the manner that Stoneham intended. Once the two-year salary for Mays was cobbled together — $165,000 for the 1972 and 1973 seasons — Stoneham knew he would have to find Willie a new home, a place where he would be happy, where he could be guaranteed this two-year salary obligation, and where his future would be secure. With the Giants revenue fading fast, Stoneham put all of his effort into getting Willie settled, and quickly.

During the spring of 1972, Stoneham entered into secret negotiations with Joan Whitney Payson, the New York Mets club owner, and M. Donald Grant, the club’s chairman, to trade Mays to the Mets. The Mets were the only club Stoneham contacted because he felt that Willie should be back in New York, where he began his great career, had so many wonderful years, and was a legend. A crucial part of the trade for Stoneham involved assurances from Payson and Grant that Willie would be given some kind of extended contract with the ballclub once his playing days were over. As befitting a sentimental and old-fashioned owner, Stoneham felt the need for secrecy in the event that the deal with the Mets might fail and Willie’s pride would be hurt, the result of feeling discarded by a cash-poor owner.30 The attempts at secrecy failed, however, and newspapers on both coasts caught wind of the story.31

On May 11, 1972, the finalized negotiations became official news. Mays was traded to the Mets for a minor-league pitcher named Charlie Williams; there was also mention of an additional unspecified amount of cash from the Mets, rumored to be between $50,000 and $200,000.32 In a gesture that conveyed the highest form of respect, Stoneham brought Mays in on the final hours of deliberation with Payson and Grant, and then ushered him to the press conference at the Mayfair House announcing the trade.33 In his remarks, the Giants owner tried to put on a brave face but could hardly hide his disappointment. “I never thought I would trade Willie, but with two teams in the Bay Area, our financial situation is such that we cannot afford to keep Willie and his big salary as well as the Mets can.”34 Grant followed by saying that the Mets planned to keep Mays around for a long time, securing his future in baseball. The player himself spoke briefly, that he was happy to be back in New York and looking forward to playing for the Mets, and that he was grateful to the Giants and to Stoneham for all they had given him.35 The press conference ended and with it one of the most fabled chapters in Giants history was over.

After the Mays trade, things hardly improved for Stoneham. In 1973 he spent most of his time denying rumors that the team was for sale.36 He was losing the public-relations battle with the A’s, who were enjoying unparalleled success — three straight World Series championships — while the Giants finished well off the pace in the National League West during the same years. He lost at the gate as well; in 1974 and 1975 the Giants’ home attendance was the lowest of any season since the team moved west, barely clearing the 500,000 mark each year. To add to all of the other distractions, his real-estate venture in Casa Grande, Arizona — a project he hoped to turn from a spring-training site into a golf resort with adjacent homes — was stalled, diverting precious capital from the running of the ballclub, “soaking up money as the quickly as the desert soaks up the rain,” as one Giants’ front office employee put it.38 After the 1974 season, Stoneham announced a $1.7 million loss to the stockholders of the National Exhibition Company.39

There was no longer any way to gloss over the obvious: The Giants were in trouble and Stoneham simply did not have the resources — nor perhaps the resolve — to solve the club’s problems. In the spring of 1975, he approached the other owners in the National League with grim news. He had enough money to meet only two months of payroll and needed a loan from the league to finish the season. At the same time, he announced his intention to sell the team, hoping to find a local buyer to keep the Giants in San Francisco.40 With this announcement, Stoneham gave notice that a 57-year family connection to Giants baseball had ended. A new era was about to begin, but the future looked anything but secure for the San Francisco Giants.

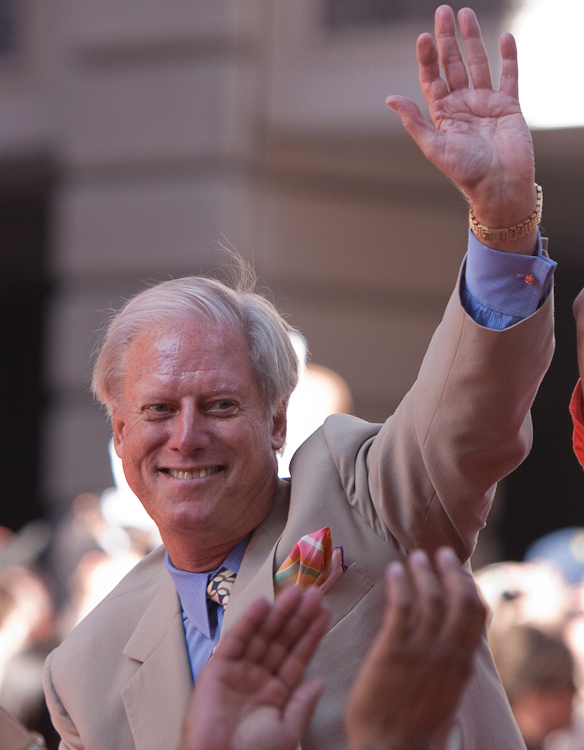

New San Francisco Giants owners Bob Lurie, left, and Bud Herseth model souvenir T-shirts after purchasing the team in 1976. (San Francisco Examiner/Newspapers.com)

Enter Bob Lurie

Throughout the summer and fall of 1975, Stoneham waited in vain for an offer to keep the team in San Francisco. Bob Lurie, a local businessman, was interested but needed a partner. Meanwhile, Stoneham grew anxious. Finally in the winter of 1975-76, a legitimate offer came from out of town, in fact from another country. A group of Canadian businessmen, some of whom were connected to Labatt Brewing Company, offered on January 9, 1976, to buy the Giants and move them to Toronto for the 1976 season. Newly elected Mayor George Moscone couldn’t imagine losing the team and put all his efforts into finding local ownership. He approached Lurie and contacted Bob Short, a Minneapolis businessman and former owner of the Texas Rangers, to help form a partnership. By late January they had agreed in principle to counter the Canadians’ offer in the hope that the major leagues would want to keep the team in San Francisco. All that remained was the approval of the NL owners who, under Los Angeles owner Walter O’Malley’s influence, were predisposed to keep the Giants in San Francisco. Everything appeared settled.

A special meeting of the NL convened on February 24, whose sole purpose was to approve the sale of the Giants. With Short in a Minneapolis hospital recovering from a bad fall, Lurie and Moscone attended the meeting and Moscone made a presentation before the owners. After the brief presentation, the mayor and Lurie waited outside the meeting room for what they assumed would be a pro-forma approval. It was with some surprise that the owners’ deliberations took longer than expected. When the owners finally came back to Moscone and Lurie, their approval had a big string attached. It was in fact a conditional approval of the sale, and the condition would prove unbearable for the partnership. The owners, troubled by Short’s history as an American League owner, preferred to deal only with Lurie as a fellow owner.41 Therefore, they demanded as a condition of the sale that Bob Lurie would act and function as the primary owner, the one who would vote at NL meetings, effectively putting Short in a secondary role in the partnership.42

It did not take Short long to respond. He immediately and emphatically rejected the league’s condition. Conversations over the next few days to reach some understanding and agreement between him and Lurie left both of them at an impasse.43 On March 2 Short sent a telegram to Lurie with a brief message dissolving the partnership. Short also sent telegrams to Moscone and Chub Feeney repeating his thinking that, given his long experience as a major-league executive and Lurie’s limited exposure to the business of baseball, he should be the primary owner. If he couldn’t, then he was out of the partnership.44

On the afternoon of March 2, Chub Feeney placed a call to a Lurie, asking for an update on the progress of the sale. A stunned Lurie explained the difficulty and asked for a 48-hour extension to find a new partner among the city’s business community. After contacting the owners, Feeney told Lurie that the league would grant him five hours. Feeney explained that the owners were too anxious about the proximity of spring training and league play to wait any longer for ownership issues. As Lurie was scrambling to find another local partner, Corey Busch, the mayor’s secretary, received a phone call from Phoenix. Someone named Bud Herseth, a cattle dealer unknown to anyone in the mayor’s office, or to baseball for that matter, was on the line asking about the sale of the Giants and if he might get involved as a partner. He had read about Bob Lurie, the difficulties of the sale, and would be interested in becoming an owner. Busch was astounded, put Herseth on hold and broke in on the mayor’s meeting. The mayor got on the line and after a few minutes decided that Herseth was serious and worthy of a follow-up. He told Herseth that someone would contact him within the hour.45

Immediately Moscone called Lurie, who then placed a call to Herseth. After a 45- minute conversation, they agreed in principle to form a partnership with Herseth providing half of the $8 million selling price. There would be no disagreement about who would be voting at the NL meetings; Herseth was fine with Lurie as the chief owner who would represent the business side of ownership. All that remained was for Herseth’s finances to be vetted. When the NL owners were satisfied with Herseth’s reliability and financial legitimacy, they approved the new partnership. The headlines the next day in the Chronicle’s sports section proclaimed the news: “Beef King Saves Lurie, Giants.”46 One writer called it “the greatest save in Giants’ history.”47 A breathless Lurie gave his account to the newspaper:

“Yesterday I was $4 million shy of the agreed sale price. Then I heard about Bud . … I called him and he said he had $4 million. I informed Feeney of this beautiful development. Chub called the owners and we got unanimous approval. … It’s all set, we own the Giants.”48

Lurie’s head was swimming, but he prevailed. He was a new owner of the Giants and the team would remain in the city.

Bob Lurie was a good fit for the Giants and San Francisco. A native son, a successful businessman who knew the social scene, an avid golfer, and a former member of Stoneham’s board of directors who knew the Giants culture reasonably well, he seemed poised to have a good run with the team. But the Lurie years would turn out to be quite uneven. After struggling his first two years with organizational issues, he eventually parted ways with Bud Herseth, buying him out in early spring of 1979. His next few years dealt primarily with managerial changes and finding the right mix in the clubhouse. The Lurie teams were occasionally good and surprising — 1978, 1981, and 1982 were good years with favorable won-lost records and first-division finishes for the ballclub. Attendance in those years was reasonable, although the Giants still hovered near the bottom of the league. After 1985, the worst season in Giants history, either in New York or San Francisco — when the club lost 100 games — Lurie made a change in management that would define his remaining years with Giants as successful and competitive, on and off the field. In September 1985 Lurie hired Al Rosen as the new GM/president, and the pair hired Roger Craig to become the team manager. With those moves, Lurie ushered in the Humm Baby era, when winning baseball came back to the city and the Giants would go to the postseason twice and eventually to the World Series.49

But even with this success, Lurie could not shake his biggest problem as owner, Candlestick Park, with its cold and windy weather, its remote location 10 miles from the city center, and its spartan and bleak appearance and atmosphere. Throughout his first 10 years of ownership, he tried everything to improve the place, only to finally realize the Giants would have to have a new ballpark at a different location. Starting in the fall of 1987, Lurie would go before the voters of San Francisco twice (1987 and 1989), Santa Clara County once (1990), and San Jose once (1992), to seek public funding to build a new ballpark. In every case the Giants lost at the polls. Knowing he couldn’t continue to run a successful franchise while playing at Candlestick and seeing no real possibilities for a new facility in the Bay Area, Lurie decided it was time for him to get out of baseball. Discouraged, he announced in early June 1992, that the team was up for sale. He arranged to take members of his front office to New York to meet with Commissioner Fay Vincent to find some remedy for his predicament. Back in San Francisco in mid-June of 1992, Lurie felt as if he had a clear direction.

But even with this success, Lurie could not shake his biggest problem as owner, Candlestick Park, with its cold and windy weather, its remote location 10 miles from the city center, and its spartan and bleak appearance and atmosphere. Throughout his first 10 years of ownership, he tried everything to improve the place, only to finally realize the Giants would have to have a new ballpark at a different location. Starting in the fall of 1987, Lurie would go before the voters of San Francisco twice (1987 and 1989), Santa Clara County once (1990), and San Jose once (1992), to seek public funding to build a new ballpark. In every case the Giants lost at the polls. Knowing he couldn’t continue to run a successful franchise while playing at Candlestick and seeing no real possibilities for a new facility in the Bay Area, Lurie decided it was time for him to get out of baseball. Discouraged, he announced in early June 1992, that the team was up for sale. He arranged to take members of his front office to New York to meet with Commissioner Fay Vincent to find some remedy for his predicament. Back in San Francisco in mid-June of 1992, Lurie felt as if he had a clear direction.

In dealing with the Giants’ dilemma, Commissioner Vincent applied the four-point standard developed by baseball in 1990 to govern franchise movement: The organization has been losing money over a substantial period; there has been declining attendance over a period of three years; the stadium is inadequate or unsuitable for baseball; and the team resides in a community that has demonstrated a lack of interest in baseball by vote or otherwise.50 Vincent reiterated these criteria to the press and added that the Giants met all of them “squarely.”51 He said: “I think the history of transfers leads one to the conclusion that baseball ought to be careful, but I think there are circumstances under which I am prepared to acknowledge that a transfer should be looked at. … San Francisco has my permission to look at these options.52

While he would subsequently refashion his meaning of “options,” Vincent initially gave all indications to Lurie that the Giants could pursue moving out of Candlestick to remedy their present situation. At the press conference after his meeting with Lurie, the commissioner confounded the issue somewhat when he added that this permission did not mean that the Giants had “automatic approval to move.”53 In stressing this last point, Vincent undoubtedly had baseball protocol in mind; all franchise sales and transfers are subject to approval by owners in both leagues. The ambiguity of Vincent’s position would, however, be a bone of contention later in the year when offers came in to buy the Giants. Nonetheless, Lurie, Rosen, and Corey Busch left the June meeting with Vincent feeling they had been given a clear go-ahead to shop the team and consider relocation. As Busch explained it, the commissioner had, in effect, granted them “a hunting license.”54

Lurie waited in vain for someone from the local community to come forward with an offer to buy the Giants and keep them in the Bay Area. But by late July, hearing nothing from locals, he began negotiating with a group from the Tampa/St. Petersburg area who wished to buy the team and move the Giants to Florida. Plans developed quickly. On August 6 a group from St. Petersburg flew to San Francisco to meet with Lurie and Rosen. By evening the parties had reached agreement: The Giants would be sold to the Florida group and begin the 1993 season in the Tampa/St. Petersburg area.

While the Florida newspapers and business community exploded with delight, the San Francisco Bay Area reacted with shock, disappointment and bitterness. Mayor Frank Jordan, claiming that the deal was far from settled, began mobilizing support for a counteroffer from the San Francisco business community. Back in New York, National League President Bill White, acting on behalf of baseball in the wake of Commissioner Vincent’s resignation, told Mayor Jordan that the National League was prepared to receive a counteroffer from a San Francisco group, but in a timely fashion. White told the mayor he had three weeks, which meant somewhere around the second week of October 1992.

With White’s deadline fast approaching, the investment partners, led by real-estate magnate Walter Shorenstein, which included the likes of Charles Schwab, Don and John Fisher, the owners of Gap clothing stores, and Peter Magowan, the CEO of Safeway, met in Shorenstein’s office on Saturday, October 10, to confront two major crises. One had to do with the calendar. White’s deadline for a competing offer was October 12. That gave the San Franciscans two days to meet the deadline. Shorenstein made one or two calls and raised a bit more capital. Larry Baer, a CBS official and a friend of Magowan’s who was working behind the scenes to help the partners, called Kevin O’Brien of KTVU, the longtime broadcaster of the Giants, and got another contribution. Shorenstein also urged the general partners to up their individual antes. In a matter of hours, the group had a substantial base of capital to go forward.55

The other crisis came in the form of a difficulty that tugged at the very identity of the group, leading to an overwhelming question: Who among the city’s movers and shakers assembled that day in Shorenstein’s office would take on the role of chief managing partner and run the franchise? There are many accounts of how this question was answered. Most describe the practicalities, that most of the partners — Shorenstein, Schwab, Don and John Fisher, for example — did not have the time or the inclination to run a baseball club, and asked Magowan if he would do it.56 Another account has it a bit more dramatically. “All at once, as if by divine providence, the heads of everyone at the meeting turned in the direction of Peter Magowan, the 51-year-old chairman of Safeway, Inc.”57 Magowan’s own, more secular version suggests that he was drafted, chiefly by Shorenstein and Baer, to secure the progress that had been made, and that if he did not accept the position, all of the group’s effort would be wasted.58 By any account, however, the move turned out to be a momentous one, solidifying the group and providing strength in leadership. Magowan was an experienced executive, but he also brought to the group a deep love and understanding of baseball, and a lifelong connection to the Giants. This affection for both the Giants and the game of baseball would energize him in the short term for the negotiations ahead, and it would prove in the long run to be a powerful guide in his role as head of the Giants’ franchise for years to come.

Armed with an agreement cobbled together over the weekend, Magowan, as newly designated chief managing partner, flew to New York on Sunday night, October 11, accompanied by Larry Baer. The offer that landed on President White’s desk the next day totaled $95 million and represented San Francisco’s official counter to the St. Petersburg bid. Magowan explained to the press after he met with White. “It is a strong, credible offer from a strong group of investors, made up almost entirely of local people.”59 In an ironic twist, one of the locals was none other than Bob Lurie himself, whose $10 million short-term loan to the partnership, the same provision he had extended to the Florida group, made him in effect the largest single contributor.60 Magowan added that he expected a decision from the baseball owners within a month.

The delivery of the competing bid did little to quiet the drama connected with the Giants sale. First there were cries of foul play coming from the Floridians, saying that White, an ex-Giant after all, was hardly a disinterested party. Next came waves of lawsuits, beginning with one from the City of San Francisco against Bob Lurie for breaking the lease on Candlestick; this was followed by one from St. Petersburg investors against San Francisco, claiming that theirs was the only legitimate bid, since Bob Lurie, the Giants owner, agreed in writing to deal only with them. Not to be outdone, the City and County of San Francisco sued St. Petersburg for interference with the contract Bob Lurie held with Candlestick Park. Tampa Bay responded, this time by naming Mayor Jordan. San Francisco then filed a counterclaim, seeking legal fees from the Tampa Bay investors and the City of St. Petersburg because they both had signed indemnification agreements with the major leagues against any damages or claims that might occur in the process of buying or selling a franchise. Law Professor Jeffrey Brand explained that the indemnification agreements would stop all the litigation in its tracks, since all of the parties, the Floridians, Bob Lurie, and the San Franciscans, had signed agreements.61 Moreover, any future development of franchise location in either city would effectively end the legal wrangling.62

Nor was Bob Lurie quiet in the days approaching the owners’ vote. He and Corey Busch began a marathon schedule in an attempt to meet with each of the owners to explain the details and benefits of the Florida offer. Much has been made about Lurie’s professional commitment to his St. Petersburg buyers, that he had given his word not to consider another offer until theirs had been given its full development. Undoubtedly, this eleventh-hour visit around the league testified to that promise. But there was also the matter of business. The Floridian offer was considerably higher than the Magowan/Shorenstein offer and owners would appreciate that. Moreover, Lurie pointed out, the San Francisco offer contained some contingencies, such as getting a loan at a financial interest rate acceptable to the buyers, that would put him further at risk.

Two days before the meeting, the San Franciscans strengthened their hand by dropping the three most restricting contingencies, one of them being the condition of a favorable interest rate, and raising their total offer to $100 million. They also received substantial help from the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. In a letter to Bill White in late October, Mayor Jordan outlined certain concessions the city would give to the Giants regarding Candlestick, including a waiver on stadium rent and the payment by the city of all utility and field-management costs.63 These would considerably ease the costs of playing games at Candlestick and help the Giants’ overall bottom line, something that would lessen the concerns of other owners.

At the November 10 meeting of the National League, the owners rejected the St. Petersburg/Tampa bid by a decisive 9-4 vote. The leading voice in opposition to the sale was Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley who, like his father in 1976 when Toronto interests sought the team, did not want to lose the Dodgers/Giants California rivalry.64 The owners’ decision freed Bob Lurie from his obligation with the St. Petersburg groups; he was now able to consider other offers for his club. A joint statement issued by Magowan and Shorenstein hinted of optimistic relief. “If Bob Lurie should decide to sell the Giants today, our group is ready to acquire the franchise.”65 Lurie, for his part, was quick to respond, indicating that he would review the $100 million offer made by the San Franciscans. For someone who had been through an emotional wringer over the past two months, Lurie sounded remarkably composed:

“I congratulate Peter Magowan, the entire San Francisco group and everyone in the Bay Area who worked so hard to keep the Giants in San Francisco. I know the feeling you have today. I had the same wonderful feeling in 1976.

… I will not be restrained from expressing my happiness that the anxiety created by the events of the past several months is finally over for Giants fans, whom I have always considered to be the greatest fans in baseball.”66

Lurie remarked that while he did not expect his review of the Magowan offer to take more than a few days, he wanted to give it his due diligence since he was its largest single investor. Bud Selig, acting on behalf of the owners, said that as soon as Lurie accepted the offer, baseball would vote on the sale, probably at the December meeting.

Reactions around San Francisco ranged from ecstatic to guarded euphoria, in keeping with a city that loves a party but cultivates a sense of cool. At Pat O’Shea’s Mad Hatter, the crowd was giddy, with an enthusiastic Mayor Jordan working the crowd and leading the “Let’s Go Giants” cheers, hoping to cash in politically on the recent turn in the team’s fortunes. In fact, unlike some of his mayoral predecessors, including Christopher and Moscone, Jordan played a minor role in the latest chapter of Giants history in San Francisco, leaving the heavy lifting to the men of finance and commerce like Magowan, Shorenstein, and the Fisher brothers. In the “Save Our Giants” movement, Jordan was more facilitator than innovator. At Perry’s on Union Street, the champagne was on the house, and orange and black balloons floated along the top of the ceiling; the mood was one of civilized revelry. At a corner of the bar sat Chub Feeney, Horace Stoneham’s nephew, former Giants vice president and former NL president, a prime witness if there ever was one to the bumpy, twisty path of Giants history, going back even to its New York days. A beaming Feeney raised his champagne glass and announced to those around him, “I am delighted.” The celebration spread throughout the city. Bars around the downtown center were jammed. Sports radio talk shows were overwhelmed with happy and relieved fans.67

Feelings were reversed in St. Petersburg and Tampa. The frustration of coming so close and then being jilted again grated on fans, bringing back the sour taste of losing the White Sox in 1988. Some said it was more of the same, a lack of respect for central Florida as a big-league venue. Others complained that the rejection was a slight on American values, that Bob Lurie should have been able to sell to the buyer of his choice; they chided Florida Senators Connie Mack III and Bob Graham for not responding sooner in a challenge of baseball’s antitrust exemption.68

Mack and Graham were instrumental in scheduling a Senate hearing in early December in Washington, but little came of it. Bud Selig, chairman of the owners’ Executive Committee — in effect the acting baseball commissioner — testified in front of the subcommittee on antitrust, monopolies and business rights, chaired by Ohio Senator Howard Metzenbaum. Selig defended baseball’s decision to keep the Giants in San Francisco, pointing out that in matters of franchise transfers Major League Baseball prefers to ban relocation except in dire circumstances. Selig also suggested that baseball’s unique antitrust exemption creates great stability in the sport:

“I am very proud of baseball’s record on franchise stability. Because of baseball’s exemption, it has by far the best record of professional sports in this area. No baseball club has been permitted to relocate since the Washington Senators moved to Texas in 1972.

… [B]aseball has not abused its antitrust exemption. … We do not allow a club to relocate simply so that the owner can earn greater profits. Indeed, the National League rejected the move to Tampa-St. Pete despite the fact that it would have netted Bob Lurie an additional $15 million.”69

California Senators Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer expressed the relief and happiness of San Franciscans and Bay Area residents that the Giants would not be moving. The two Florida senators went on record to register their disappointment about St. Petersburg’s loss, but little headway was gained by the hearings. The subcommittee had no intention of challenging baseball’s long-standing exemption to antitrust laws, nor to reversing any action by baseball regarding franchise relocation.

Despite the jubilation in San Francisco, official business lay ahead. “It is still Bob Lurie’s franchise,” Larry Baer said.70 But things were indeed falling into place. After a period of review and consideration, Lurie accepted the San Francisco offer. Then it was a simple matter of bringing the agreement to the owners for their approval. Having given so much time and consideration to the Giants’ case, the owners found little to trouble them. The discussion at baseball’s winter meeting was largely pro forma. The combined NL-AL assembly voted 27 to 0 to approve the sale and the transfer of the Giants from Bob Lurie to the Magowan partnership. Once again, at the eleventh hour with a local purchase, the Giants would remain in San Francisco. And once again, under yet another ownership, the franchise faced an uncertain future in the same ballpark that had troubled them for over 30 years.

The Magowan Years

With Magowan as chief managing partner, Giants ownership entered a new phase of organizational structure, away from the single-owner model to an administration that is more corporate, with a board of directors and the head officer of the franchise emerging from the board and reporting back to them. For the next 15 years, from 1992 through 2007, Peter Magowan would head and run the organization, with Larry Baer as his chief assistant. The new ownership hit the ground running. They hired Dusty Baker to manage the club and signed Barry Bonds to what was then (in the winter of 1992) baseball’s most lucrative contract, six years at $43.75 million; they refurbished Candlestick as best they could with new paint, improved concessions stands with an upgraded menu, a new grass playing field, padded fences to replace the chain-link, and 2,500 new seats in left field so fans could catch home-run balls; they made the place more fan-friendly by hiring more ushers and conducting periodic sweeps throughout the games to clean up wind-blown litter. More important, perhaps, they embarked on a bold new plan to find a new ballpark downtown.

With Magowan as chief managing partner, Giants ownership entered a new phase of organizational structure, away from the single-owner model to an administration that is more corporate, with a board of directors and the head officer of the franchise emerging from the board and reporting back to them. For the next 15 years, from 1992 through 2007, Peter Magowan would head and run the organization, with Larry Baer as his chief assistant. The new ownership hit the ground running. They hired Dusty Baker to manage the club and signed Barry Bonds to what was then (in the winter of 1992) baseball’s most lucrative contract, six years at $43.75 million; they refurbished Candlestick as best they could with new paint, improved concessions stands with an upgraded menu, a new grass playing field, padded fences to replace the chain-link, and 2,500 new seats in left field so fans could catch home-run balls; they made the place more fan-friendly by hiring more ushers and conducting periodic sweeps throughout the games to clean up wind-blown litter. More important, perhaps, they embarked on a bold new plan to find a new ballpark downtown.

Magowan and Baer began their planning slowly at first, in conversations in the fall of 1995, musing about their favorite baseball venues and sharing impressions of the parks they had visited. They then moved to more practical considerations to develop a strategy to go forward. Given the recent history of the Giants’ failed ballots on public financing, Magowan understood that a new stadium could not be built with public money. As both he and Baer explained the problem, “[W]e needed a new approach; we had to get the community to see the ballpark in a new light. And that meant one thing: private financing.”71 But the new approach would require more than creative thinking; it would require the hard work of diplomacy, working the corridors of City Hall and downtown businesses, and diligence in winning over the skeptics in the community. Privately constructed ballparks were a rarity in recent baseball history. The last one to be built was Dodger Stadium, finished in 1962.

The daunting practical side of campaigning for the ballpark was eased somewhat by an accompanying exercise of conjuring up the perfect stadium and of dreaming about what it would look like. Both Magowan and Baer had a penchant for the old, traditional locales like Fenway Park in Boston or Wrigley Field in Chicago. Combining an aesthetic sense with an historical one, they conceived of the ballpark as a special place, reflecting both the uniqueness of the sport itself and the environs where it would be built. Their planning grew out of the traditional side of baseball. “We wanted our park to evoke the feeling of the best of the old parks, with Wrigley and Fenway as our models. … Both were intimate, grass-field parks. Both had distinct features that let you know where you were.”72

The Giants had their location; the Port of San Francisco had agreed to lease them a 12.7-acre bayfront parcel in China Basin, south of Market Street but close to the Embarcadero. A sense of this location became a powerful concept for both Magowan and Baer as seen in their instruction to the stadium’s architectural team, Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum, Sport, Venue and Event (HOK-SVE). The firm had built Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore, Jacobs Field in Cleveland, and the new Busch Stadium in St. Louis.73 “We contacted the only architect we wanted to work with: Joe Spear of HOK Sport. …We urged him to dream and to draw, to create something fitting for the site. What we envisioned was a ballpark more compelling, more distinctive than any other of recent memory.”74

Magowan and Baer wanted that location to permeate the design not only of the ballpark’s façade, but also the playing field. China Basin is tied to San Francisco’s maritime history as a place where nineteenth-century clipper ships sailed to and from China, giving the location its name. By the late twentieth century, the area had evolved from an industrial waterfront to warehouses and offices. The 12.7-acre parcel set aside for the ballpark was bordered on one side by King Street, a major traffic artery, and on the other by the edge of the bay, in the proximity of warehouses and some offices. It was seen by many in the city as an area primed for development. As Magowan and Baer explained, “The best ballparks … are created not by an architect; they’re created by a site imposing itself on the architect.”75

With his deep interest in Giants’ history, Magowan also wanted the design of the park to honor the team’s heritage, from its days in New York as well as its time in San Francisco. Spear obliged that interest with countless examples of the ballclub’s rich and storied past. The recent past is represented in various locations outside the park by a number of nine-foot bronze statues of former San Francisco Giants, all of them Hall of Famers: Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal, and Orlando Cepeda. On the exterior wall of the right-field façade, world championship titles from New York and San Francisco are painted, along with NL pennant years, and plaques of various players. The waterway edge of San Francisco Bay behind the right-field wall, named McCovey Cove in honor of the Giants’ left-handed home-run slugger, would prove to be a unique and popular feature of the ballpark, where kayakers and boaters would gather to wait for “splash hits,” home-run balls that land in the water.76 In a large stone adjacent to McCovey Cove, plaques commemorate highlight moments in each of the seasons the Giants played in San Francisco. The pictorial exhibit on Giants’ history on the club level runs chronologically from right field, featuring the early days in New York with John McGraw and Christy Mathewson, running clockwise throughout the years and ending in left field with AT&T Park. The sense of baseball history extends even to the San Francisco Seals, the old Pacific Coast League team; their beloved manager, Lefty O’Doul, has a plaza named for him outside the right-field entrance to the ballpark.

Magowan also worked with Spear on the interior playing field, especially on how it would be influenced by its location and the dimensions of the site. Features of the playing field would evolve from its own small dimensions and the proximity of the water. Magowan thought that the restriction of space could dictate an interesting irregular outfield that would have an impact on how the game would be played. Unlike football or basketball, where the playing dimensions are fixed, baseball, aside from the infield measurements, always had irregularities in the old parks like Fenway, the Polo Grounds, Ebbets Field, and Shibe Park in Philadelphia. At the China Basin site, the right-field dimensions would be restricted by the close proximity of the water, only 309 feet from home plate in the corner, but would quickly run away from the plate toward right-center, which would be 421 feet at its deepest. The left-field foul line would be 339 feet and 399 in straightaway center field. There would be sharp angles in both right-center and left-center. The right-field wall would be 24 feet high (another historical gesture — an homage to Willie Mays, who wore number 24) to prevent easy home runs down the line, and also add to the dramatics of “splash hits” that land in McCovey Cove. Magowan’s interest in the fans’ perspective would limit the dimensions of foul territory as well, since the seating is designed to get the fans as close to the action, especially behind home plate and near the infield.

The dreaming came easily to both Magowan and Baer, as did their collaboration with Spear. They now faced the difficult parts: how to get public support for their planning, and then find a way to pay for it. The first step was to put a ballot measure before the San Francisco voters to gain approval for the construction of the ballpark. While it would be built with private funding, the Giants still needed public approval to remove certain restrictions that applied to the Port’s China Basin site and to change some of the infrastructure before they could begin construction. The Board of Supervisors authorized a special March 1996 election in which Proposition B would come before the voters of the City and County of San Francisco. Prop B, as it came to be known, involved land-use restrictions, the most important of which were to increase the limitations on building height from 40 to 150 feet and to waive parking requirements near the ballpark.

In the buildup to the vote, Magowan and Baer wasted no effort in cultivating strong citywide support for the measure. While the terms of Prop B differed from previous referenda in making no demands for public money to build the park, Magowan and Baer were wary about possible negative residue carrying over from the 1987 or 1989 ballpark ballot defeats. They hired a professional political consultant, Peter Hart, who recommended polling in those neighborhoods that voted “no” in the 1987 and 1989 ballpark referenda. As part of the campaign, they approached three important community leaders in the city to head a “San Franciscans For a Downtown Ballpark” committee, State Senator Quentin L. Kopp, Roberta Achtenberg, and Rev. Cecil Williams, each of whom represented a different constituency in the city’s social and political fabric.77 The campaign then began to solicit support from a number of individuals who could coalesce into strategic groups and be listed in the official San Francisco Voters Pamphlet. Leaving no stone unturned, Magowan and Baer managed to convince nine people who voted no on the two previous city ballpark measures to stand as another group in the Voters Pamphlet entitled “Old Foes, New Supporters of a Downtown Ballpark.”78 Weeks prior to the vote, Magowan and Baer made their way around town with a scale model of the new ballpark, displaying it at prominent venues for voters to see.

All the planning, organizing, polling, and campaigning paid off for the Giants in a stunning victory at the polls. Proposition B was approved by San Francisco voters by a substantial majority of 66 percent. The local papers celebrated the news. “Giants Ballpark: Home Run” ran the headlines in the San Francisco Examiner; “S.F. Voters Say Play Ball” was the headline in the Chronicle.79 Politicians, campaign workers, Giants officials, and average baseball fans celebrated all over town, including at the Double Play, a bar where supporters of Proposition B toasted the home team.

Once the vote was approved, Magowan and Baer could get to work on the financing. The projected cost of building the ballpark was $357 million. Magowan explained that from the outset the plan to raise capital was multifaceted. The first stage was a brilliant marketing ploy aimed at 1996 season-ticket holders. Over the following winter they received a promotional package in a cardboard box shaped like home plate. Inside was a pop-up view of the new ballpark, a film showing an architect’s rendering, with information about the design and construction, and a brochure on the charter seat program. The mailing campaign proved quite successful. The sale of charter seats coupled with an advertising campaign provided much-needed capital. Magowan and Baer were pleased with the results: “We raised $75 million by selling licensing fees at $5,000 for the best seats.”80

They then moved to get corporate sponsorship for ads within the ballpark. Naming rights were $50 million; other advertising brought in $50 million. With this amount of capital commitment, they looked to borrow the rest. Their first choice was Bank of America, an old San Francisco bank with ties to the Giants. Walter Shorenstein owned the Bank of America building and Bob Lurie was one of the tenants. But Bank of America said no. They then pursued another bank with a local history, Wells Fargo, but they also said no.81 Finally, Magowan and Baer traveled to New York City and presented their plan to Chase, which approved the loan. The City of San Francisco also provided some help. Using a tax-increment financing plan, the city provided $12 million in infrastructure (amenities outside the ballpark including closing streets, street lighting, a transit stop, and utilities connections).82

AT&T Park in San Francisco, circa 2009. (Photo courtesy of Eric Molina via Flickr.com. Used under Creative Commons 2.0 license.)

************

Magowan and Baer had accomplished what had been previously thought improbable. They had overcome all the disappointments, false starts, and near misses of recent Giants attempts at trying to build a new ballpark. They had managed to get City Hall, the community, local businesses, and neighborhood groups to support the idea of a downtown baseball venue at a location agreeable to all. With public approval and the crucial financing in hand, they now had a “shovel ready” project. On December 11, 1997, they broke ground at China Basin and the building of the new ballpark was on its way. Pacific Telephone and Telegraph of California had paid $50 million for the naming rights; the new stadium would be called Pac Bell Park. Magowan and Baer hired Kajima, a Japanese construction management firm, to coordinate the building of Pac Bell. Kajima in a sense “rode herd” on the structural engineers and the construction company, Haber, Hunt & Nichols.83 The two Giants executives visited the construction site almost on a daily basis to keep up with the progress, a far cry from Horace Stoneham’s passive connection to the building of Candlestick.84 The attention to detail and the superb management of the project produced spectacular results. Pac Bell Park opened on April 11, 2000, 27 months after the groundbreaking ceremonies. The Giants finally had their downtown home. Coming full circle from Opening Day on the West Coast 42 years before in Seals Stadium, the Giants’ opponent in the first game at Pac Bell Park was the Los Angeles Dodgers, a fitting historical echo at the dawning of a new century of baseball in San Francisco.

Once Pac Bell Park opened in 2000, there was a dramatic shift in attitude, perception and the team’s fortunes. To many in San Francisco it was love at first sight. Players marveled at the playing field and locker-room facilities. Taken by the ambience and location, fans flocked to the park, establishing sellouts for every home game. The longtime voice of the Giants, Lon Simmons, suffered through many cold nights at Candlestick; when he first saw Pac Bell Park, he remarked, “Finally the Giants have a ballpark that looks like San Francisco.”85 The neighborhood around the park throbbed with life and activity. Mike Krukow, one of the Giants’ broadcasters, noticed the way the ballpark immediately connected with the city’s character. “It was an old soul the day it opened. You had the feeling it was in San Francisco even before the bridges.”86

The coherence and sheer beauty of the new ballpark brought the deficiencies of Candlestick into sharper focus. Everything about Pac Bell accentuated the gap between the new and the old: the location of the ballpark amid a thriving neighborhood; the attractive combination of brick and steel in the façade; the proximity of downtown; the views of the Oakland hills from the upper decks; the sight of the Bay Bridge from the right-field seats; even the weather was better, due to adjustments to the ballpark’s configuration after some wind studies. There was nothing like any of this at the remote location of Candlestick, 10 miles from downtown. After only one month in the new ballpark, players, fans, broadcasters, and sportswriters alike shuddered to think of Giants baseball at Candlestick.

The dramatic comparison of appearance and the location between Pac Bell and Candlestick extended also to the fortunes of the home team. For the 40 years the Giants played at Candlestick, they went to the postseason five times; they won division titles three times and the NL pennant twice. They won no World Series. Once they moved into Pac Bell Park in 2000, things changed quickly. In their first four years there, the Giants went to the postseason three times and won a NL pennant. Overall, in the 16 years (as of 2015) that they have played at AT&T Park (the ballpark changed its name in 2004 to SBC Pac Bell, and then in 2006 to AT&T Park), the Giants have been to the postseason seven times, have won four pennants and three World Series.

The dramatic comparison of appearance and the location between Pac Bell and Candlestick extended also to the fortunes of the home team. For the 40 years the Giants played at Candlestick, they went to the postseason five times; they won division titles three times and the NL pennant twice. They won no World Series. Once they moved into Pac Bell Park in 2000, things changed quickly. In their first four years there, the Giants went to the postseason three times and won a NL pennant. Overall, in the 16 years (as of 2015) that they have played at AT&T Park (the ballpark changed its name in 2004 to SBC Pac Bell, and then in 2006 to AT&T Park), the Giants have been to the postseason seven times, have won four pennants and three World Series.

The move to the new ballpark has strengthened and cemented the Giants connection to the city of San Francisco, as well as enhanced its status as one of the great franchises in baseball. According to national journals like Forbes or business internet sites like bizjournals.com, the Giants rank in the top five major-league baseball franchises for profitability, team worth, success on the field, and overall stability. A good example of that stability can be seen in the smooth succession of recent corporate management. When Peter Magowan retired in 2008, Bill Neukom became chief managing partner; and then in 2012, when Neukom left, Larry Baer became the chief executive of the franchise, an organization that no longer is run by a single owner like Stoneham or Lurie, but has a board of directors to whom the chief managing partner reports.87 During this period of change, the ball club has remained not just efficient and secure, but phenomenally successful.

Last revised: September 5, 2018

ROB GARRATT is an emeritus professor of English and American Literature. A lifelong Giants fan, he is the author of “Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants.”

Notes

1 Stoneham was born in April 1903.

2 Robert E. Murphy, After Many a Summer (New York: Union Square Press, 2009), 38-42; Frank Graham, The New York Giants: An Informal History (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952), 248; Andrew Goldblatt, The Giants and the Dodgers: Four Cities, Two Teams, One Rivalry (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2003), 82-84.

3 The Giants drew 824,112 in 1955. Cincinnati drew 693,662 and Pittsburgh 469,397. By contrast, Brooklyn drew 1,033,589 and the New York Yankees 1,490,138..

4 Stew Thornley, Land of the Giants (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), 102, 112; Goldblatt, The Giants and the Dodgers, 138.

5 Up until the late 1940s, fans could walk along with the players and umpires, who were heading toward the clubhouses in center field, to reach the gates in left-center and right-center. After an altercation between Leo Durocher and a Brooklyn fan, Commissioner Happy Chandler ruled that fans would have to wait until the players and umpires cleared the field before they would be allowed to use the center-field exits. Thornley, Land of the Giants, 102.

6 Goldblatt, The Giants and the Dodgers, 138-139.

7 Arthur Daley, reflecting on the project, which would be huge, remarked that there was a limit to “giantism,” even for the Giants. New York Times, May 15, 1956.

8 New York Herald Tribune, April 12, 1956.

9 For a good summary of Jack’s idea see Murphy, After Many a Summer, 178-181.

10 The Sporting News, May 15, 1956. See also The Sporting News, February 8, 1956.

11 The Sporting News, May 30, 1956.

12 walteromalley.com, “Historical Documents,” March 23, 1957.

13 The full details of the move have been treated in a number of studies. Stoneham was also in conversations with Walter O’Malley at the time and the encouragement by the Dodger boss had some effect on Stoneham’s decision. See Andy McCue, Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers and Baseball’s Westward Expansion (Lincoln, Ne: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 357; Robert F. Garratt, Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 16-28.

14 Duns Review, May 1964: 44.

15 San Francisco Chronicle, April 12, 1960. (Hereafter SFC).

16 For a more complete discussion of the travails of Candlestick’s origins see Garratt, Home Team, 43-59.

17 The Sporting News, November 4, 1967.

18 Art Rosenbaum, SFC, October 12, 1967.

19 SFC, October 19, 1967.

20 San Francisco Examiner, October 12, 1967; October 14, 1967; October 19, 1967 (hereafter SFE); SFC, October 12, 1967; October 15, 1967; October 20, 1967.

21 SFC, October 19, 1967.

22 SFC, October 12, 1967.

23 The overall total attendance for Giants and A’s baseball in the Bay Area between 1969 and 1975 remained about what the Giants were drawing from 1960 to 1968, the year Oakland arrived. This is surprising, especially when one considers the great baseball Oakland was playing in the early 1970s when they won three consecutive World Series.

24 John Thorn et. al., eds, Total Baseball, Sixth Edition, 107.

25 Shirley Povich, Washington Post, February 20, 1973.

26 baseball-reference.com/players/m/mccormi03.shtml.

27 baseball-reference.com/players/p/perryga01.shtml; baseball-reference.com/players/l/lanieha01.shtml.

28 baseball-reference.com/players/d/dietzdi01.shtml.

29 davekingmanfan.com/.

30 Charles Einstein, Willie’s Time: Baseball’s Golden Age (Carbondale, Il: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), 329.

31 New York Herald Tribune, May 6, 1972; SFE, May 6, 1972, New York Times, May 10, 1972.

32 SFC, May 12, 1972; SFE, May 12, 1972.

33 Los Angeles Times, May 11, 1972; Boston Globe, May 11, 1972.

34 The Sporting News, May 20, 1972.

35 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend (New York: Scribner’s, 2010), 508.

36 Los Angeles Times, July 4, 1972.

37 1976 San Francisco Giants Media Guide, 495.

38 John Taddeucci, interview with the author, June 12, 2014.

39 Los Angeles Times, April 30, 1975; SFE, April 29, 1975.

40 The Sporting News, May 24, 1975.

41 For a truncated, albeit opinionated view of Short’s ownership activities. see Glenn Dickey, “Don’t Prolong the Agony,” SFC, January 26, 1976

42 SFC, February 26, 1976.

43 SFC, March 2, 1976; SFE, March 3, 1976.

44 SFC, March 3, 1976; Los Angeles Times, March 3, 1976.

45 Corey Busch, interview with the author, June 17, 2014.

46 SFC, March 3, 1976.

47 San Francisco Giants Magazine, 1978.

48 San Francisco Giants Magazine, 1978.

49 “Humm Baby” was a phrase manager Roger Craig used throughout 1986 spring training whenever he saw a great play, a good at-bat, or good hustle from his team. The phrase stuck as a description of the Rosen/Craig era in Giants baseball history.

50 New York Times, June 12, 1992; The Sporting News, June 22, 1992.

51 New York Times, June 12, 1992.

52 SFC, June 11, 1992; St. Petersburg (Florida) Times, June 19, 1992.

53 Los Angeles Times, June 12, 1992.

54 Michael Tuckman, “Sliding Home,” California Lawyer, April 1993; Corey Busch, interview with the author, June 17, 2014.

55 Richard Rapaport, “Fast Balls and High Finance”: California Business, September 1993, 55.

56 SFE, October 13, 1992.

57 Tuckman, “Sliding Home”: 66.

58 Peter Magowan, interview with the author, June 25, 2013.

59 SFC, October 13, 1992.

60 Bob Lurie’s contribution was in the form of a four-year loan. SFE, October 16, 1992.

61 Jeffrey Brand, “Off the Field: A Legal Donnybrook”, California Lawyer, April 1993.

62 St. Petersburg/Tampa was awarded an expansion franchise in 1995.

63 Mayor Frank Jordan to President William White, National League, October 20, 1992. Frank Jordan Papers. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

64 Los Angeles Times, November 9, 1992; Peter O’Malley, interview with the author, September 22, 2011.

65 SFC, November 11, 1992.

66 Ibid.

67 Ibid.

68 SFE, November 11, 1992.

69 U.S. Senate. Hearings before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Monopolies and Business Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary. One Hundred Second Congress, second session, on the Validity of Major League Baseball’s Exemption from the Antitrust Laws, December 10, 1992.

70 SFE, November 16, 1992.

71 Peter Magowan and Larry Baer, “The Miracle at China Basin,” in Joan Walsh and C.W. Nevius. Splash Hit!: Pacific Bell Ballpark and the San Francisco Giants, (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001), 19.

72 Ibid.

73 Maureen Smith, “From ‘The Finest Ballpark in America’ to ‘The Jewel of the Waterfront:’ The Construction of San Francisco’s Major League Stadiums,” The International Journal of the History of Sport, Vol. 25, No. 11, 118.

74 Magowan and Baer, Miracle at China Basin, 19.

75 Ibid.

76 McCovey Cove was particularly crowded during the period when Bonds was chasing the home-run record.

77 Quentin Kopp, a conservative politician, was wary of using public funds for private projects and did not support the other two ballpark initiatives in San Francisco. Roberta Achtenberg, a former Board of Supervisors member, was a prominent attorney and Democratic politician, and the first openly lesbian government official approved for a government position by the United States Senate. Rev. Cecil Williams was pastor of Glide Memorial Church and a leading advocate for African-Americans, gays, and lesbians. Williams’s church grew to a congregation of 10,000 and provided many social services in the city.

78 Germaine Wong, San Francisco Voter Information Pamphlet and Sample Ballot. (San Francisco: Office of the Registrar, the City and County of San Francisco, 1966), 63-65.

79 SFC and SFE, March 27, 1996.

80 Peter Magowan, interview with the author, June 25, 2013.

81 Peter Magowan, interview with the author, June 3, 2015.

82 Kevin Delany and Rick Eckstein, Public Dollars, Private Stadiums: The Battle over Building Sports Stadiums, (Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003), 195. Tax-increment financing (TIFs), used throughout the country by local municipalities to promote development, diverts property taxes on the land into the construction costs. See Joanna Cagan and Neil deMause. Field of Schemes: How the Great Stadium Swindle Turns Public Money into Private Profit. (Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, 1998), 175.

83 Kajima News and Notes, Summer 2000, Vol. 13: 3. Newsletter of the Kajima Corp.

84 Peter Magowan, interview with the author, March 29, 2016.

85 Quoted in Brian Murphy, San Francisco Giants: Fifty Years, (San Raphael, Ca: Insight Editions, 2008), 179.

86 Ibid.

87 For a more complete discussion of recent Giants ownership and corporate structure see Mark L. Armour and Daniel R. Levitt, In Pursuit of Pennants (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 368-384.