New York Giants team ownership history

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

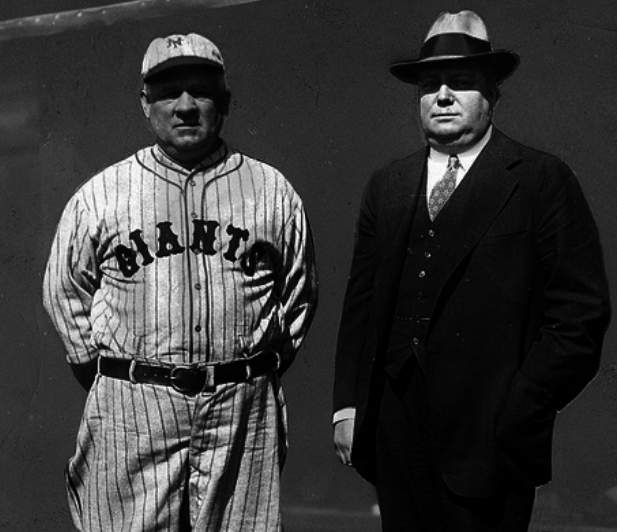

New York Giants manager John McGraw, left, and team owner Charles Stoneham in the early 1920s. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

INTRODUCTION

The New York-San Francisco Giants baseball club is among the most storied franchises in the annals of professional sport. To fans, mention of the club’s name promptly evokes images of Willie Mays, Christy Mathewson, Barry Bonds, John McGraw, Mel Ott, Juan Marichal, and other towering figures in the game. Over the decades, the talents of these and other headliners have propelled the Giants to 23 National League pennants, eight world championships, and more game victories than any other team in major league history.1 This essay focuses upon the endeavors of less-celebrated but no-less-vital contributors to franchise success: the club’s owners, presidents, and other front office executives. Largely by means of biographical portrait, we chronicle the founding of the club in Manhattan in early 1883 and recall its management history, financial ups-and-downs, and ballpark problems through the visionary, if locally traumatic, relocation of the franchise to the City by the Bay in 1958. Thereafter, the Giants’ more modern franchise story through its latest World Series title in 2014 is explored. We begin this saga, however, with a man who was neither New Yorker nor San Franciscan, club founder John B. Day.

John B. Day

The New York Giants were the offspring of an earlier baseball venture by John B. Day. Despite New York City’s status as the nation’s largest metropolis, its business and financial center, and a hotbed of 19th century baseball, the city did not host a team in the first professional baseball league, the National Association of 1871-1875. Nor did the city have an entry when the National League was formed in 1876, as the club commonly known as the New York Mutuals made its home in Brooklyn, America’s third-most populous urban center and then a municipality separate and distinct from New York City.2 The man who would bring major league baseball to New York City proper was a Connecticut cigar manufacturer and avid amateur ballplayer recently arrived in Manhattan for business purposes. His name was John Bailey Day.

The New York Giants were the offspring of an earlier baseball venture by John B. Day. Despite New York City’s status as the nation’s largest metropolis, its business and financial center, and a hotbed of 19th century baseball, the city did not host a team in the first professional baseball league, the National Association of 1871-1875. Nor did the city have an entry when the National League was formed in 1876, as the club commonly known as the New York Mutuals made its home in Brooklyn, America’s third-most populous urban center and then a municipality separate and distinct from New York City.2 The man who would bring major league baseball to New York City proper was a Connecticut cigar manufacturer and avid amateur ballplayer recently arrived in Manhattan for business purposes. His name was John Bailey Day.

From an early age, Day had been a baseball enthusiast, fancying himself a pitcher. Once in New York, the 33-year-old tobacco man organized and played on various amateur nines in and around the city. This led to a fateful encounter with Jim Mutrie, an unaccomplished player in assorted New England circuits then at loose ends in Manhattan. Mutrie had energy, a keen eye for baseball talent, and considerable organizational ability. Their partnership led to the first team that could legitimately call New York City home. The team was called the New York Metropolitans, established in early September 1880.

To effectuate his ambitions for the club, Day incorporated the Metropolitan Exhibition Company (MEC). After playing the 1881 and 1882 season as an independent nine and twice capturing the championship of the National League-affiliated Eastern Championship Association, the Metropolitans were more than ready for admission to the major leagues. Indeed, Day had previously turned down invitations to place the Mets in National League or its newly-arrived rival, the American Association. But over the 1882-1883 off-season, the club boss unveiled his expansive master plan.

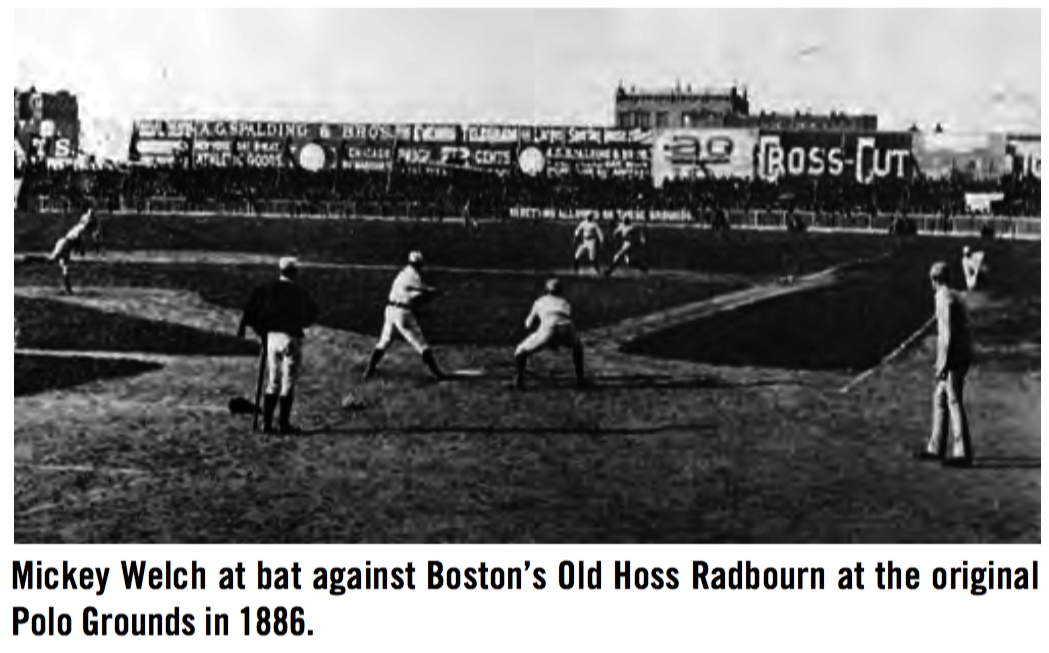

To some surprise, Day again declined an invitation to place the Metropolitans in the National League, the longer-established and more prestigious of the two major circuits. Rather, the Mets joined the American Association, with Mutrie continuing as field manager. Thereafter, Day boldly announced that an entirely new MEC-owned ball club would be placed in the National League. The nucleus of this team, at first sometimes called the Gothams or simply the New-Yorks, would consist of budding stars like catcher Buck Ewing, first baseman Roger Connor, and pitcher Mickey Welch, plucked from the roster of the recently liquidated NL Troy Trojans. Standout Providence Grays pitcher-infielder John Montgomery Ward would also be wearing a New York uniform. The remainder of the squad would be formed from free agents, cast-offs, and other nonentities. Veteran backstop-manager John Clapp would do the on-field direction, while Day himself would serve as club president.

To accommodate the two major league teams that would be using the Polo Grounds, a second diamond with separate grandstand was laid on the property. As accorded with its preferred status as Day’s team, the NL club – soon to be known as the New York Giants – were given the established field on the southeast corner of the Polo Grounds. The Mets were consigned to a new, landfill-based playing surface situated on the southwest quadrant of the grounds. When the Giants and Mets played home games simultaneously, the two diamonds were separated by only a temporary canvas fence, an awkward arrangement that occasionally required outfielders from one league to chase long hit balls onto the field of a rival circuit.3 Differences in standing between the two MEC teams were reflected in the gate, as well. The carriage trade sought by Day for the Giants was charged 50 cents general admission, while the working classes cultivated by the Mets got in for a quarter. Potent liquid refreshment, however, was available at each venue, Day defying the league-wide ban on alcohol sales at NL games.

The aspirations of the MEC brain trust were confounded in 1883. Behind the stellar pitching of 41-game winner Tim Keefe, a Troy acquisition whom management had deemed unworthy of a Giants roster spot, and the astute generalship of Mutrie, the Mets finished a respectable fourth (54-42-1, .563) in the AA pennant chase. The Giants, meanwhile, could do no better than a disappointing sixth (46-50-2, .479) in NL final standings. Club president Day took mild consolation in the fact that his club had drawn more patrons (75,000) to the Polo Grounds than had the Mets (50,000), but neither club was near the fan attraction of their respective league leaders (NL: Boston Beaneaters, 128,968; AA: Philadelphia Athletics, 305,000).4 Still, the combined attendance of the two New York clubs would have been good for fourth (out of 16 major league teams) in a fan patronage race, and with only one ballpark for the MEC to maintain, financial prospects looked promising.

Events continued to disconcert Day during 1884. The Giants rose no higher than tied-fourth place in NL standings, and the MEC was embarrassed by the late-season need to dismiss new club manager James Price, caught for a second time embezzling funds from Giants coffers.

Events during the off-season manifested John B. Day’s intention to make champions of the Giants. And to achieve that end, the Mets would be crippled. First, manager Mutrie was transferred to the National League team. Thereafter, he assisted Day in some rule-bending chicanery to bring Mets stars Keefe and Dude Esterbrook over to the Giants.5 A gutted and dispirited Mets team played out the season but plummeted to seventh place in AA standings. But that was of little concern to Day and his MEC associates. In December 1885, the Mets were sold for $25,000 to amusement impresario and local railroad magnate Erasmus Wiman who promptly relocated the club to Staten Island.6

Fortified by its new acquisitions (which also included future Hall of Fame outfielder Jim O’Rourke (late of Buffalo), the Gothams posted a dazzling 85-27 (.759) record in 1885. But same was only good for second place in the NL, as the Cap Anson-led Chicago White Stockings had been two games better. In addition to a change in fortunes, the New York team underwent a name change, as well. During the early part of the 1885 season, the New York Gothams acquired the handle Giants, the moniker by which the team would become famous.7 More important to the MEC bottom line, the club had become the league’s leading draw, with 185,000 fans paying their way into the Polo Grounds, and was well on its way to becoming the National League’s vanguard franchise.

As the standing of his team increased in the NL, the stature of club president Day among his fellow magnates rose with it. With dominant team owners A.G. Spalding (Chicago) and John I. Rogers (Philadelphia), Day was chosen to represent the league on the important Joint Rules Committee of Organized Baseball. He was also appointed to the NL Board of Arbitration and became a heeded voice in executive conclaves. Meanwhile, top salaries, first-rate road accommodations, and bonhomie – John B. was on familiar terms with many of his charges – garnered the New York club boss esteem and good will in player ranks.8

In 1888, the Giants players rewarded Day’s amity by bringing home the National League pennant. And a record-setting 305,455 paid admissions to the Polo Grounds swelled MEC coffers. New York then made its triumph complete by downing the AA St. Louis Browns in a post-season match of league champions. Unfortunately, the club did not fare as well against a different adversary: city planners determined to complete the local traffic grid by running a street through the Polo Grounds outfield. From the beginning, Central Park North residents had resented the intrusion of a baseball park into their upper crust neighborhood, and their political emissaries on the city council had finally pushed through a scheme for removing it – the opposition of Tammany Hall notwithstanding.9 Rearguard legal action had forestalled the street improvement project from commencing while the 1888 season was in progress, but by early the following year it had become evident that the Giants would have to find a new playing field.

Manhattan-born Joseph Gordon, a real estate-savvy Tammany politico who joined the MEC in May 1885, informed Day that grounds might be available in far north Manhattan. But Day was unable to reach agreement with James J. Coogan, the estate agent for the site’s owners, the vastly-propertied Gardiner-Lynch family.10 Frustrated, Day then placed an extraordinary advertisement in the New York Times which solicited an angel to come forth and purchase the property, and then lease it to Day for $6,000 per year.11 To no great surprise, the needed intermediary failed to materialize, leaving Day’s ball club without a home field as Opening Day 1889 loomed on the horizon.

In desperation, the Giants began the season in Oakland Park, an undersized facility in Jersey City. After two games there, the club switched to the St. George Grounds on Staten Island, erstwhile home to the now-defunct Mets. But poor weather and an inconvenient locale proved a serious drag on fan attendance. So the search for a suitable ballpark site continued. In time, Day reentered negotiation with Coogan12 regarding the Gardiner-Lynch property, a grassy tract located at 155th Street and 8th Avenue in upper north Manhattan, hard by the Harlem River. Although in sparsely populated territory far removed from mid-town and bordered to the north by a 175-feet high escarpment later dubbed Coogan’s Bluff, the intended playing grounds were flat, vacant, and most important, serviced by a station on the New York & Northern elevated railway. In early June, agreement was reached on a five-year leasehold. But in a decision that he would soon have occasion to regret, Day declined to rent the entire tract. Instead, he leased only as much property as was needed for the construction of a new ballpark. Within a remarkable three weeks thereafter, the small army of workman engaged by Day had erected a usable, if unfinished, ballpark on the property. When completed that winter, this handsome facility would seat more than 14,000 and be named the New Polo Grounds.13

On July 8, 1889, the Giants inaugurated their new home field with a 7-5 victory over Pittsburgh, a harbinger of the second-half surge that would see New York nip the Boston Beaneaters at the wire for the NL pennant. The Giants then successfully defended their world champions title, defeating the AA Brooklyn Bridegrooms behind the hurling of unlikely mound heroes Cannonball Crane and Hank O’Day.14 Ballpark problems had reduced the season’s home attendance to 201,989, but over a five-year span the club had drawn well over 1 million fans.15 EN Counting modest revenues contributed by the ownership and sale of the Mets franchise, the New York Times calculated that the operation of their ball clubs had netted Day and his junior MEC partners a profit of $750,000 in the less-than-ten years of the corporation’s existence. Although an exaggeration – no MEC club ever reported a single-season profit in excess of $50,000 – operation of its ball clubs had proven a reliable moneymaker for corporation principals. Doubtless, anticipation of continued profits from his now two-time defending world champion club prompted Day to turn down the $200,000 offer for the Giants tendered late in the 1889 season by Polo Grounds landlord Coogan.16 Within months, however, calamitous events would thrust the thriving franchise to the brink of bankruptcy.

The Talcott Group

John B. Day’s enjoyment of the Giants’ second championship campaign was tempered by a sense of foreboding. The 1889 season had been conducted amidst simmering player discontent, longstanding player resentment of the reserve clause having been exacerbated by the imposition of a tight-fisted salary classification scheme, adopted by the National League over Day’s objection. Even as the Giants rallied for the pennant, plans for a new major league, one controlled by the players themselves, were taking shape. Ominously, the chief promoters of this nascent rival, from visionary organizer John Montgomery Ward to lead player recruiters Tim Keefe and Jim O’Rourke, all wore a New York Giants uniform.

John B. Day’s enjoyment of the Giants’ second championship campaign was tempered by a sense of foreboding. The 1889 season had been conducted amidst simmering player discontent, longstanding player resentment of the reserve clause having been exacerbated by the imposition of a tight-fisted salary classification scheme, adopted by the National League over Day’s objection. Even as the Giants rallied for the pennant, plans for a new major league, one controlled by the players themselves, were taking shape. Ominously, the chief promoters of this nascent rival, from visionary organizer John Montgomery Ward to lead player recruiters Tim Keefe and Jim O’Rourke, all wore a New York Giants uniform.

On November 4, 1889, the players’ intention to form a new major league was publicly announced.17 As New York was the very font of rebellion, Day’s Giants would be particularly hard hit by player defection. The Giants quickly lost the team’s entire everyday lineup to the Players League, save for aging pitcher Mickey Welch and outfielder Mike Tiernan. To counteract the attrition, the National League formed a War Committee chaired by the hard-nosed Spalding, with Day and Rogers as the other members. The two leagues then began maneuvering. Ward and his comrades, genuinely fond of Day and eager for a defection in NL ownership ranks, attempted to entice Day to their side by offering him a lucrative position in PL executive offices. Ever the NL loyalist, Day refused and was soon busy trying to lure PL enlistees – notably Giants star Buck Ewing and second baseman Danny Richardson – back to the NL fold. But to no avail.18 Thereafter, Day adopted a litigation strategy, instituting reserve clause-based suits against Ward, Keefe, Ewing, and O’Rourke. The courts entertaining such actions, however, were uniformly unsympathetic, declining to grant Day relief in any form.

With his roster depleted and the start of the 1890 season on the horizon, Day took the first of the steps that would hasten his departure from the game: he tendered Indianapolis team owner John T. Brush a $25,000 note in exchange for Jack Glasscock, Jerry Denny, Amos Rusie, and other players under contract to the just-liquidated Hoosiers franchise.19 Long-term implications aside, the move yielded immediate benefits. Day would now be able to put a presentable nine on the field. And he would need to, for the inter-league competition in New York would be cutthroat. In a display of hubris and disdain, War Committee chairman Spalding arranged the National League schedule to place his league’s teams in direct head-to-head completion with the upstart PL whenever possible. This made the atmosphere in New York particularly fraught, as the circuits’ rival clubs would be doing battle in the closest of quarters.

The prime architect of the Players League franchise in New York was Wall Street financier Edward Baker Talcott. Of privileged birth – his lineage descended from 17th century English settler gentry and his father was a wealthy banker and commodities broker – Eddie Talcott (as the sporting press referred to him) was an avid baseball fan and one-time amateur club pitcher.20 By 1883, the former “boy broker of Wall Street” had become a wealthy 35-year-old and a Polo Grounds regular. When Giants slugger Roger Connor hit a tape-measure home run during the 1889 season, “Eddie Talcott, broker and baseball fan, jumped up and started a collection. … [Spectators who] chipped in [included] Col. [Edwin] McAlpin and [Albert] Johnson. They gave Roger a big gold watch.”21 But Talcott, tobacco company tycoon McAlpin, and street car magnate Johnson were up to more than just taking in ball games together. Each was preparing to assume a pivotal role in the oncoming Players League. Johnson would provide crucial seed money for the new circuit. McAlpin would become league president, and Talcott would chart the course of the PL’s cornerstone franchise, the PL New York Giants.

Incorporated in Albany as the New York Base Ball Club Limited, the franchise’s chief financial backers were Talcott, McAlpin, Pittsburgh stockbroker (and reputed McAlpin brother-in-law) Frank B. Robinson, and New York City Postmaster Cornelius C. Van Cott. Executive positions were doled out, with Van Cott assuming the post of club president. But Talcott did most of the lifting, including the securing of playing grounds for the PL operation. Despite his pre-existing relationship with John B. Day, New Polo Grounds landlord Coogan had no compunction about leasing the adjoining property to Talcott. And soon, a brand new 16,000 seat edifice (Brotherhood Park) sat directly alongside the New Polo Grounds, the two ballparks separated by no more than their stadium walls and a ten-foot-wide alley.22

The fan allegiance question was settled on Opening Day when 12,013 attended the debut of the star-laden Ewing Players League Giants, while only 4,644 chose to watch Day’s National League Giants play next door. As the season progressed, both teams drew poorly, but the NL club suffered more, attracting little more than one-third the fans of the PL Giants. With five major league clubs (NL New York Giants, PL New York Giants, NL Brooklyn Bridegrooms, PL Brooklyn Ward Wonders, and AA Brooklyn Gladiators) playing in greater-Gotham, there simply were not enough fans to keep New York professional baseball viable. Awash in cash only a season earlier, the cost of new stadium construction and expensive litigation had taken a significant toll on MEC finances. And when dwindling gate receipts failed to cover operating expenses, the NL Giants quickly sank into the red.23 Summoned to a private meeting convened in Brooklyn in mid-July 1890, NL magnates were stunned by the degree of their New York club’s fiscal distress. Only infusion of $80,000 would avert franchise bankruptcy. To avoid the collapse of the league’s flagship franchise, A.G. Spalding orchestrated a financial bailout on the spot, pledging $25,000 to Day in return for stock in the Giants. Boston boss Arthur H. Soden did the same, while Brooklyn owner Ferdinand Abell and Philadelphia co-owner Al Reach made smaller investments in Giants shares. John T. Brush, meanwhile, agreed to convert Day’s outstanding $25,000 player payment note into a Spalding/Soden-sized stake in the Giants operation.24 When word of the arrangement leaked, the press took to referring to the strapped team owner as John Busted Day. And the process through which Day would lose control of the New York franchise had been set in motion. But in the short term, the financial aid had the desired effect, and the NL Giants managed to stagger to the 1890 season finish line, its 63-68-4 (.481) record good for sixth place.

While the PL Giants had achieved a more competitive third-place (74-57-1, .565) finish and far outdrawn their NL counterparts at the gate (148,876 to 60,667), the Talcott group had also lost buckets of money. And unlike Day (and silent Giants minority shareholders like Spalding and Brush), the PL club backers were not die-hard lovers of the game, in for the long haul. To the contrary, the Talcott group viewed Players League baseball mainly as a business venture, and expected a prompt and reliable return on their investment. This made them receptive to settlement overtures from their next-door rivals. Preempting larger National League-Players League consolidation talks, Day and Talcott swiftly reached an agreement to merge the two New York teams, cutting out John Montgomery Ward and his Players League directory in the process. Day, a one-time friend of the renegade players, had been adamant that player representatives be excluded from NL-PL merger discussions. Said Day, “The players have nothing to say at all. The capitalists on both sides will do the negotiating. The players will have to do what they are told to do.”25 Talcott concurred, brushing off objections by Ward. “I don’t propose to have Mr. Ward or anybody else criticize my business methods,” declared Talcott, testily. “Nor shall I allow Mr. Ward to tell me how my financial interests must be arranged. The fight cannot go on another year, for baseball will become a dead sport. Ward can say what he likes but it cannot alter matters with us a particle.”26 With its New York operation co-opted, the Players League soon passed from the baseball scene, its remaining backers scrambling to reach consolidation or buyout agreements with National League counterparts. By late-November 1890, a triumphant A.G. Spalding could accurately proclaim, “The Players League is as dead as the proverbial doornail.”27

While it may have been dead, the brief existence of the Players League had exacted a fearsome toll on the fortunes of John B. Day. Competitive pressures had drained MEC coffers and prompted Day to tap his personal funds to keep the Giants afloat. And when this proved inadequate to the task, Day had been forced to seek monetary aid from fellow NL club owners, whose combined investment in the New York franchise now exceeded Day’s own. The subsequent issuance of bonds to cover franchise indebtedness reduced Day’s ownership share even further.

On January 24, 1891, the concerned parties met to reorganize the franchise under the laws of New Jersey. The proceedings were dominated by the Talcott group, which now held almost half of the Giants stock. Other NL owners (Spalding, Soden, Brush, et al.) controlled just over one-quarter combined, while the stake of John B. Day and his MEC associates had been reduced to about 15 percent. Former PL organizers Ward, Keefe, O’Rourke, plus a few others held the remaining odd stock lots.28 The new organization was christened the National Exhibition Company (NEC), the corporate handle used for all the ensuing years that the New York Giants would be in existence. The respected Day was bestowed the title of club president, but executive power would be wielded by Vice-President Talcott and his allies.

An early sign of Talcott ascendency was embodied by the selection of the team’s playing site for the 1891 season. Day had built and paid for the New Polo Grounds less than two years earlier and the stadium was a fine baseball venue. But Brotherhood Park was the home base of the Talcott forces, and Talcott himself was responsible for the ten-year lease that the PL Giants had signed with landlord Coogan. With no intention of having an idle ballpark on his books, Talcott had Brotherhood Park renamed the Polo Grounds and designated as the permanent playing field for the New York Giants. Day’s adjoining stadium was re-titled Manhattan Field and relegated to hosting college football, track meets, horseracing, and other secondary sports. Day’s diminished stature in the new Giants operation was also reflected in the treatment of his old friend and collaborator Jim Mutrie. Although continued as Giants manager at Day’s insistence, Mutrie was shorn of effective command, supplanted in authority by Buck Ewing, the former PL Giants field leader. At the conclusion of the 1891 season, Mutrie was unceremoniously severed from franchise employ, with Day powerless to prevent it. John B. continued to hold the title of club president for another season but was now little more than a figurehead.

The next season was a trying one for New York, both on the field and at the gate. The 71-80-2 (.470) Giants of 1892 were mediocre non-contenders, and Polo Grounds attendance (130,566) remained only a fraction of the crowds attracted only four years earlier. Meanwhile, the Talcott group increased its grip on franchise operations by purchasing the bonds that had to be issued to cover club indebtedness.

In February 1893, Day resigned. He was a good man and a lifelong lover of baseball, but deeply-ingrained traits of personal rectitude and institutional loyalty left Day ill-equipped to deal with the fast-changing baseball scene of the early 1890s and the cold-blooded entrepreneurs who had entered the game with it. At a farewell meeting of franchise stockholders, John Montgomery Ward, a small-stake Giants shareholder, offered a motion of thanks to the departing club chief. Although he and Day had had their differences, Ward pronounced himself “deeply aggrieved to see Mr. Day retire from the presidency.” The motion was thereupon seconded by John T. Brush who added “a glowing tribute to Mr. Day as a baseball president, a companion and a gentleman.” Upon unanimous adoption of the testimonial, Day, “overcome with emotion,” could do no more than reply, “I thank you, gentleman.”29 And with that, the founding era of the New York Giants passed into history.30

Andrew Freedman

Following Day’s departure, Cornelius Van Cott assumed the post of club president. But as before, the franchise course would be steered by Edward B. Talcott, the New York Herald reporting that it was “an open secret that [Van Cott] has but little knowledge of the national game and that Mr. Talcott will be ‘the power behind the throne.’”31 Having reconciled with John Montgomery Ward, now manager of the NL Brooklyn Dodgers, Talcott decided to improve club prospects through securing the accomplished Ward for the Giants. For $10,000 or a share in Giants gate receipts – accounts differ – Ward was acquired as player-manager for the 1893 season.32 Shortly after his installation at the helm, Ward dispatched aging Giants icon Buck Ewing to Cleveland for young infielder George Davis, whose Hall of Fame career blossomed once in a Giants uniform. With fireballer Amos Rusie performing yeoman work on the mound and Ward and Davis anchoring the infield, the Giants began to climb in NL standings. Attendance surged as well, with the 387,000 patrons drawn to the Polo Grounds during the 1894 season setting a major league attendance record. Capping the Giants campaign was a four-game sweep of the NL pennant-winning Baltimore Orioles in the 1894 Temple Cup match.

Following Day’s departure, Cornelius Van Cott assumed the post of club president. But as before, the franchise course would be steered by Edward B. Talcott, the New York Herald reporting that it was “an open secret that [Van Cott] has but little knowledge of the national game and that Mr. Talcott will be ‘the power behind the throne.’”31 Having reconciled with John Montgomery Ward, now manager of the NL Brooklyn Dodgers, Talcott decided to improve club prospects through securing the accomplished Ward for the Giants. For $10,000 or a share in Giants gate receipts – accounts differ – Ward was acquired as player-manager for the 1893 season.32 Shortly after his installation at the helm, Ward dispatched aging Giants icon Buck Ewing to Cleveland for young infielder George Davis, whose Hall of Fame career blossomed once in a Giants uniform. With fireballer Amos Rusie performing yeoman work on the mound and Ward and Davis anchoring the infield, the Giants began to climb in NL standings. Attendance surged as well, with the 387,000 patrons drawn to the Polo Grounds during the 1894 season setting a major league attendance record. Capping the Giants campaign was a four-game sweep of the NL pennant-winning Baltimore Orioles in the 1894 Temple Cup match.

Notwithstanding the improvement in Giants fortunes, it appears that baseball club ownership had not produced the financial return anticipated by its commerce-minded ownership group, and by late-1894 Talcott in particular wanted out. The timing of events could not have been better for Andrew Freedman, a young Manhattan real estate millionaire who had already begun quietly acquiring shares in the New York club.33 Apart from personality differences – Talcott was polished and personable, Freedman volatile and prickly – the two men had much in common. Both were intelligent and handsome, astute in financial matters, and influential Tammany Hall insiders. In January 1895, Talcott delivered a slim but working majority of New York Giants stock into Freedman’s hands. And at a bargain price, too, variously estimated between $48,000 and $54,000.34 For the next eight seasons, the New York Giants would be controlled by a club boss soon deemed the most-hated man in turn-of-the-century baseball.

Andrew Freedman was born in midtown Manhattan on September 1, 1860, the second of four children born to well-to-do German-Jewish immigrants. His father Joseph was a prosperous businessman, variously described in census reports as a silk importer, dry goods merchant, and realtor.35 By the time that Andrew was born, there were already servants in the Freedman home and he was raised in comfortable circumstances. A precocious but indifferent scholar, young Andrew (he hated the nickname Andy which everyone used, but not to his face) dropped out of City College of New York after his freshman year and began his working life at age 16 as a clerk in a wholesale dry goods house. But he soon gravitated to real estate, the field where he would make his first fortune.36

In 1881, 21-year-old Andrew Freedman made the move that would dictate the course of his adult life: he joined Tammany Hall, the corrupt political machine that controlled the Democratic Party in New York City. There, Freedman became a protégé of Richard Croker, the shrewd, ruthless, and unapologetically avaricious politico who assumed control of Tammany in late 1885. While he may not have invented it, Croker perfected “honest graft,” the protection money that a Tammany-controlled NYPD collected from every saloon, brothel, betting parlor, dance hall, drug den, and other outpost of the Manhattan demimonde. During the Croker reign, Tammany coffers filled to overflowing, with Boss Croker and those close to him becoming very wealthy in the process. This included Andrew Freedman. What first drew the two men together is uncertain, but in time Croker and Freedman became both business associates and close, lifelong friends.37

Frank Graham, Noel Hynd, and other New York Giants historians have portrayed Freedman as an uncouth lout, and his failings – arrogance, a ferocious temper, and mean-spiritedness – are undeniable. But Freedman was also a man of formidable abilities. He was smart, possessed of fierce energy, and had extraordinary business acumen. Indeed, Freedman had an absolute genius for making money. During his lifetime, he would amass fortunes in three separate fields: (1) real estate, (2) municipal bonding, insurance, and finance, and (3) subway construction. In addition, Freedman was a savvy investor in the corporate endeavors of other entrepreneurs (including the Wright brothers).

The first of these fortunes was made in real estate where Freedman’s high-priced services were regularly retained by property owners, construction firms, city contractors, and others requiring the favor of Boss Croker. The Freedman real estate business flourished and by the early 1890s, he had become very wealthy. But Freedman’s revenue sources were not confined to real estate. Tammany-friendly judges often appointed him to lucrative fiduciary positions such as business conservator, bankruptcy trustee, or estate guardian. And in early 1893, Freedman’s appointment as trustee of the financially-failing Manhattan Athletic Club (MAC) led to his introduction to major league baseball.

Freedman was not an athlete himself and never played any sports, as far as is known. But his stewardship of the MAC included oversight of operations at Manhattan Field (nee New Polo Grounds), only recently the home field of the New York Giants, now playing next-door at Polo Grounds III (originally Brotherhood Park). With the premises no longer needed by the Giants, the lease to Manhattan Field had been acquired by the MAC for use by its baseball, football, and track teams, and for rental for other activities. As the lease was a prime asset of the MAC, the operation of Manhattan Field required the attention of trustee Freedman, who frequently visited the stadium to ensure proper administration of the revenue-generating events (harness racing, track meets, college football) conducted there. Freedman would later maintain that his interest in baseball stemmed from dropping in on Giants games played at Polo Grounds III while on his rounds at Manhattan Field.38

Freedman took a quick liking to the game and quietly began gathering stock in the Giants in 1894, often using proxies to disguise his interest in the franchise. Freedman accelerated his stock acquisition after Tammany lost the New York City municipal elections in November and Boss Croker temporarily withdrew to his estates in the British Isles. In January 1895, Freedman publicly acknowledged his intention to assume control of the Giants.39 By month’s end and with Talcott facilitating matters, he had captured working command, acquiring the additional shares needed to take the club over. According to sportswriter O.P. Caylor, the shares previously acquired by Freedman and those obtained from Talcott, E.A. McAlpin, J. Walter Spalding, Frank Robinson, C.C. Van Cott, and John Montgomery Ward combined to give Freedman 1,191 shares of Giants stock, or eight more than needed for an absolute majority.40 At a board of directors meeting conducted days thereafter, Freedman assumed the mantle of club president. The new club commander wanted Talcott to remain on the Giants board, but Talcott declined “for personal reasons.”41 Still, Talcott got his successor off on the right foot, arranging a meeting between Freedman and Polo Grounds landlord Coogan where the two political adversaries “buried the hatchet.”42 Talcott also furnished the incoming regime with a ringing endorsement. “I have no hesitation in saying that the incoming [Giants] Board will be the finest body of men which ever represented a baseball club,” he said. “They are all men whose standing in the commercial world is the very best.”43

Talcott was not the only one singing the praises of the new club boss. Wealthy, politically connected, and a native son, Freedman’s acquisition of the club was generally well-received. The New York Herald predicted that the new owner “will wear well … He is young, with excellent business ideas, liberal in his dealings, pronounced in his ideas of right and wrong, and quick to recognize an advantage.”44 Even future adversaries applauded. A.G Spalding stated that while he did not know Freedman personally, “judging from what he had heard … metropolitan patrons of the game need not worry about the future of the sport in this city,”45 while John Montgomery Ward – whose 30 shares transfer had been crucial to Freedman attaining majority control of Giants stock – approved the new magnate, particularly after Freedman ratified Talcott’s appointment of Ward favorite George Davis as Giants playing manager for the upcoming season.46 Overlooked in the glow of the good feeling was a dubious opening move by Freedman. Despite being a novice owner with limited prior contact and understanding of the game, he eliminated the post of managing director of the club. As club president, Freedman would oversee Giants operations personally.

With the nucleus of the 1894 Temple Cup champions returning (sans the retired John Montgomery Ward), great things were expected from the Giants.47 But the team started the new season sluggishly. Impatient New York scribes were quick to assign blame as did Giants fans, and the new team president was not exempted from their censure. Combative and surprisingly thin-skinned, Freedman reacted badly. He began by firing his managers. Davis, Jack Doyle, and Harvey Watkins would all be relieved of duty by season’s end. Freedman also had troubles with his players, particularly star hurler Amos Rusie who chafed under the owner’s disciplinary measures.48 Nor did Freedman enjoy cordial relations with his fellow magnates, most of whom found Freedman abrasive and impossible to get along with.49 Worse still, Freedman got into fights – at times literally, for he was ill-tempered and quick with his fists – with writers on the Giants beat, at times denying them admittance to the Polo Grounds or refusing to communicate about club matters.50 Led by New York American sportswriter Charles Dryden, the baseball press retaliated by publishing imaginary interviews with Freedman, complete with maladroit quotes designed to make the cosmopolitan Giants owner appear an ignoramus.51 A public relations nightmare, Freedman quickly managed to alienate most of the baseball world. In the meantime, his Giants team staggered home a disappointing ninth-place finisher (out of the 12-team National League).

Whatever his troubles elsewhere, Freedman encountered little opposition at Giants headquarters. Apart from a fractious relationship with board member J. Walter Spalding (A.G. Spalding’s younger brother and business partner), NEC directors supported Freedman policies and practices almost reflexively. Nor did minority Giants shareholders like John T. Brush and Arthur Soden challenge Freedman’s running of the club, notwithstanding their frequent opposition to him in National League executive council meetings. Freedman, for all practical purposes, personified the New York Giants franchise. That franchise, however, was headed for another rocky season in 1896. Crippled by the absence of Rusie, who sat out the entire season rather than capitulate to tight-fisted salary terms, the Giants finished a distant seventh in NL standings, 27 games behind pennant-winning Baltimore. In the off-season, the Freedman/Rusie impasse was finally resolved via the unofficial intervention of fellow NL team owners. Alarmed by the threat posed to the reserve clause system emanating from a federal lawsuit filed on Rusie’s behalf by newly-minted attorney John Montgomery Ward, these owners endorsed a Brush proposal to settle the lawsuit out-of-court for $5,000 – all without Freedman’s knowledge or consent. Indignant when he found out, Freedman refused to contribute to the settlement and fumed at the magnates’ intrusion into his operation of the Giants.

Despite all the headaches he caused, Andrew Freedman was pretty much a dilettante when it came to owning the Giants. Like the collection of French landscape paintings, opera patronage, and yacht racing, guiding a baseball club was essentially a pastime for Freedman, a diversion from the weighty political and business affairs that consumed his life. As a consequence, his stewardship of the franchise was mercurial, with highly publicized battles with his players, fellow club owners, and the baseball press alternating with extended periods of Freedman indifference to Giants’ fortunes. Nowhere is this best exemplified than in 1897. With Rusie back in uniform and George Davis (.355, 10 home runs, a NL-leading 136 RBIs, and 65 stolen bases) playing a superb shortstop, the Giants surged in league standings. But in the midst of an exciting pennant chase, Freedman did what many wealthy New Yorkers did to escape the August heat: he sailed for Europe. Oblivious to baseball, he spent the next six weeks taking the waters and plotting a Tammany comeback in the November elections with Boss Croker. The (83-48-7, .634) third-place finish was easily the Giants’ best during the Freedman years, but paled in significance for the club owner compared to Tammany’s smashing victory at the polls on Election Day. Ever the backstairs operative, Freedman declined office in the administration of in-coming Mayor Van Wyck, but, at Croker’s insistence, he assumed the post of treasurer of the National Democratic Party.

When not attending to political concerns, Freedman busied himself with the formation of the Maryland Fidelity and Guarantee Company, a municipal bonding, insurance, and finance venture that would yield him a second fortune. But a now-rare visit to the Polo Grounds in July 1898 for a game against the Baltimore Orioles precipitated the incident that would cast a pall upon Freedman’s legacy as Giants owner. Full accounts of the Ducky Holmes affair can be found elsewhere.52 For here, suffice it to say that Freedman, enraged by the umpire’s refusal to take action following an anti-Semitic slur loudly uttered by ex-Giant Holmes, ordered his club off the field, triggering a forfeit. The $1,000 game forfeiture fine subsequently imposed on the Giants aggravated Freedman further, while the season-long suspension imposed on Holmes infuriated Baltimore, as well as players throughout the league. The truly pivotal event, however, was the stance publicly adopted by other National League team owners. Deeming Holmes’ suspension illegal (because it had been imposed without first affording Holmes a hearing), the magnates sided with Holmes and urged the lifting of the sanction on him. This development stunned Freedman, who viewed the controversy as a matter of honor and respect. In Freedman’s mind, the magnates’ position and the ensuing official reinstatement of Holmes represented nothing less than league countenance of a gross personal insult. And Freedman would not abide it.

Freedman’s revenge took the form of a punishing financial lesson for NL club owners. Although Freedman adversaries like Cincinnati’s John T. Brush and Baltimore’s Harry Vonderhorst were prosperous businessmen, they lacked the wherewithal to conduct their baseball operations at a loss indefinitely. Andrew Freedman was different. While not in the plutocrat class of a Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, or Carnegie, Freedman was truly wealthy, with a personal fortune that was likely the equal of his fellow magnates put together.53 As Freedman did not need income from the Giants – he drew a $100,000 annual salary from Maryland Fidelity alone – he would suffer no great injury if Giants performance nosedived and the club lost its appeal at the gate.54 But real pain would be felt by other club owners, particularly those in smaller markets (like Cincinnati and Baltimore) who relied greatly upon games against New York to bolster revenues. Immediately after the Holmes imbroglio, Giants fortunes plummeted, with the 1899 squad posting a non-competitive 60-90-3 (.400) record, finishing a full 42 games behind pennant-winning Brooklyn. Repelled by the situation and with no end in sight, fans avoided Giants games in droves. Attendance at the Polo Grounds shrunk from a league-leading 390,340 in 1897 to 121,384 in 1899, and Giants drew only small crowds on the road.

The league’s distress gave Freedman no end of satisfaction. As the Giants’ dismal 1899 season drew to a close, Freedman declared, “Base ball affairs in New York have been going just as I wished and expected them to go. I have given the club little attention and I would not give five cents for the best base ball player in the world to strengthen it.”55 And as even his detractors knew, Freedman meant it.

With their horizons bleak and certain of Freedman’s ruthlessness, NL owners soon entreated for peace. But reconciliation with Freedman would come at a high price. First and foremost was submission to Freedman’s demand for reduction of the NL to an eight-club circuit and the elimination of syndicate team ownership – the twin policy prescriptions that fig-leafed the deeply personal nature of Freedman’s bitterness toward the league. The owners also acceded to his demand that the Giants receive the pick of the players available from the liquidated teams. In addition, the league agreed to reimburse Freedman the $15,000 that the yearly rent of Manhattan Field cost him, lest the grounds become available for some future competitor. Last but an important matter of principle to Freedman, the NL refunded the $1,000 fine imposed upon the Giants for forfeiting the Ducky Holmes game – with six percent interest.56

Another ramification of the mollification process was the emergence of a wholly unexpected alliance between Freedman and longtime nemesis John T. Brush, the league’s most influential magnate and heretofore leader of the Freedman opposition in NL owners ranks. Following a meeting with Brush arranged by Boston owner (and minority Giants shareholder) Arthur Soden, Freedman informed the baseball press: “I have patched up the differences I had with John T. Brush and acknowledge it with pleasure. We will now work on the most friendly terms and will work in harmony for the best interests of the sport.”57

The baseball press and most fellow club owners were mortified by the prospect of Freedman and Brush working in concert, and with good reason. But little immediate benefit from the Freedman/Brush collaboration accrued to their respective franchises, as the Giants and Reds alternated as the league’s cellar dwellers for the 1900 and 1901 seasons. This may have been because both men had larger endeavors on their mind than the immediate pennant races. Freedman, in fact, had taken to almost entirely ignoring the Giants, his energies devoted to the task that would yield his most enduring memorial: construction of the Interborough Rapid Transit line, New York City’s first underground railway system.58 Brush, meanwhile, was busy at work on a longtime pet project, a scheme to convert the independent franchises of the National League into a jointly-held trust.59 As Brush envisioned it, NL assets would be pooled into a holding company managed by a board of regents. Players and managers would be licensed by the board and assigned to various teams consistent with establishing competitive parity. Costs would be controlled by means of stringent salary caps and by the manufacture of baseball equipment by a Trust subsidiary. Apportioned profits to trust shareholders would be meted out at season’s end.60 The trust scheme was scuttled at contentious NL winter meetings held in early 1901, spawning a court battle that trust opponent A.G. Spalding won on the public relations front, but lost in court to the Freedman legal corps.

By now, baseball club ownership had lost its charm for Andrew Freedman, and the trust debacle may have finalized his intention to depart the game.61 But before he took his leave, Freedman assumed a supporting role in a 1902 Brush plot to disassemble the Baltimore franchise in the upstart American League, and thus preclude its imminent relocation to New York. Although this scheme eventually failed, as well, it did yield an incidental but long-lasting benefit: the engagement of disgruntled Orioles manager John McGraw as new field leader of the New York Giants.

In August 1902, Freedman announced that he had appointed John T. Brush managing director of the Giants, and transferred day-to-day control of club operations to him.62 Freedman retained the title of club president, but not for long. Six weeks later, he severed most connection with the club, selling all but a few shares of his majority interest in club stock to Brush for a reported $200,000.63 Still, Freedman remained an actor to be dealt with by major league baseball. Although the fall of Boss Croker following Tammany’s crushing defeat in the 1901 New York City municipal elections had stripped Freedman of much of his political influence, his superintendence of the massive subway project still gave him considerable sway over New York City real estate – a power that he would now exercise. Whether prompted by a sense of obligation to Brush, disdain of American League president Ban Johnson, or sheer malice, Freedman stymied AL entrance into Manhattan for months, condemning for putative subway purposes any possible ballpark site that Johnson had shown interest in. With the start of the 1903 season looming, only the acquisition of a desolate north Manhattan mesa overlooked by Freedman afforded the AL a foothold in New York.64 After that, Freedman withdrew from the New York baseball scene.

In retrospect, the eight years of the Freedman regime can fairly be judged the darkest in New York Giants history. The team had been a contender only once during that span (1897) and had reached bottom (a 44-88-5 last-place finish) by the time Freedman abandoned the game. Chronically impatient with his club’s standings, he inflicted 13 managerial changes on the Giants during his tenure as majority club owner. Worst yet, Freedman’s peevish battles – with his players, NL umpires, fellow owners, league officials, the sporting press – and his ferocious vindictive streak drained vitality from baseball’s flagship enterprise and hurt the game itself in the process.

In the ensuing decade, Freedman continued to prosper, adding to his fortune via various business endeavors. At the time of his death from a stroke in December 1915, he had accumulated an estate estimated at $7 million, almost all of which the life-long bachelor left to charity. By that time, the fortunes of the New York Giants had also rebounded – the legacy of an exceptionally congenial pairing of an astute club owner with a baseball-savant manager.

The Brush-McGraw Years

On the surface, John T. Brush and John McGraw seemed an oddly-matched pair. A generation older than his manager, the new club boss was dour, often inscrutable, and physically frail, his body long-ravaged by the effects of locomotor ataxia, a painful wasting disease. The Giants field leader was the opposite: feisty, often voluble, and near bursting with energy and good health, the very antithesis of John T. Brush. Their differences notwithstanding, the two men, both spawn of a grim, impoverished childhood in upstate New York, had immense regard for one another. And they worked almost perfectly together. The decade of the Brush-McGraw collaboration would see the New York Giants attain the club’s first period of sustained success.

Reams have been written about John McGraw, one of early-20th century baseball’s most celebrated figures. The following will focus on his now nearly-forgotten senior partner. John Tomlinson Brush was born on June 15, 1845 in Clintonville, New York, a remote hamlet situated near the Canadian border. The beginnings of his life were the stuff of Dickensian melodrama. His father, the first John Tomlinson Brush, died a month before his namesake’s birth. Mother Sarah Farrar Brush succumbed in 1850, orphaning five-year-old John and his three older siblings. Taken in by a severe paternal grandfather, young John spent most days tending to the exhausting drudgery of farm work and nights sleeping in an unheated barn.

Brush set off on his own at age 17, taking a brief course of study at Eastman’s Business College in Poughkeepsie before enlisting in the First New York Artillery Regiment in September 1864. By the time he reached 20, he was a battle-tested Civil War veteran. Mustered out unscathed in June 1865, Brush proceeded to Troy where, in time, he was befriended by George Pixley, a principal in a newly-formed retail clothing business. Within ten years, Brush advanced from clothing salesman to store manager to partner in Owen, Pixley & Company. Along the way, he married Margaret Agnes Ayres, a woman about whom little is known except that her marriage to John T. appears to have been a troubled one. Daughter Eleanor Gordon Brush, destined herself to be a somewhat significant figure in New York Giants history, was born in March 1871.65

In 1874, Brush was dispatched to Indianapolis as Owen, Pixley expanded operations westward. After frustrating delays, a company outpost whimsically named the When (as in When will it finally open?) Store opened its doors in March 1875. With consumer interest whetted by Brush’s unlikely flair for advertisement and promotion, the operation was a resounding success, eventually becoming the largest department store between New York and Chicago.66 The store’s boss, meanwhile, immersed himself in the civic affairs of his new hometown, and soon became a leading figure in assorted community and fraternal organizations.

Not an athlete himself (although he once claimed, implausibly, to have been a catcher in his youth), John T. first seized upon baseball as a vehicle for promoting his business. But he quickly became infatuated with the game. In 1882, Brush organized a municipal baseball league, constructing a diamond with grandstand in northwest Indianapolis and hiring future major leaguer John Kerins as player-manager for the When Store team. When the professional game mushroomed to three major leagues in 1884, Indianapolis was granted an American Association franchise. Historical accounts differ on whether or not Brush owned the one-year AA Indianapolis Hoosiers, but it seems more likely that Joseph Schwabacher, “a local liquor dealer beat Brush to the franchise.”67

In the years that followed, Brush’s interest in baseball only intensified. First, he placed an Indianapolis nine in the newly-formed Western League, only to see the circuit collapse around his league-leading Hoosiers. Brush then became the driving force behind local acquisition of the National League St. Louis Maroons and the relocation of that club to Indianapolis. In time, he acquired a controlling interest in the new Indianapolis franchise and assumed the post of club president. In addition to running his own club, Brush promptly threw himself into the administration of NL affairs, sitting on various of the league’s policy-making boards.

The adoption of one Brush initiative, a tight-fisted salary classification plan, was a major cause of the player revolt that led to the debilitating Players League War of 1890. Ironically, Brush himself was one of the conflict’s first casualties, the National League liquidating his non-competitive Indianapolis club (and weakling Washington, as well) as a preemptive wartime measure. Brush, however, had no intention of being forced to the sidelines. He exacted stiff reparations from the league, remained a member of the NL owners council, and obtained the promise of the next available franchise from his fellow magnates. Thereafter, at the clandestine meeting of NL club owners organized by A.G. Spalding to bail out the financially-failing New York Giants, Brush agreed to the conversion of the $25,000 note for Indianapolis players earlier given him by Giants boss John B. Day into stock in the New York franchise. Like Spalding, Boston’s Arthur H. Soden, and other new Giants stakeholders, Brush made no attempt to intrude on Day’s operation of the New York club. But acquisition of the stock fired a new Brush ambition: gaining control of the New York Giants for himself.

Fulfillment of that ambition would be deferred for more than a decade. For the short term, Brush turned his attention to Cincinnati, outmuscling one-time Players League angel Al Johnson for the new National League franchise allotted to the Queen City. Brush was delighted to once again have control of a major league baseball club, but his experience in Cincinnati would prove an unsatisfying one. Brush declined to relocate, maintaining his residence in Indianapolis. Thereafter, when the Reds were generally a non-contender in NL pennant races, the absentee club owner became a favorite target of local press critics, particularly sportswriter-editor Ban Johnson of the Cincinnati Commercial-Gazette.

Brush’s disappointment with the Reds was counterbalanced by new-found joy in his personal life. In 1894, Brush – his long-estranged first wife having died six years previously – married Elsie Boyd Lombard, a stage actress little older than his daughter Eleanor. A year later, the birth of baby Natalie increased the Brush household.68 The vivacious Elsie was a natural hostess, and soon the Brush estate, named Lombardy in her honor, became a regular stopping place for theater stars, literary lions, and other celebrities sojourning in Indianapolis. Meanwhile, Eleanor Brush married an earnest Philadelphian named Harry Hempstead, a union that would soon provide John T. with a trusted business subordinate and two grandchildren. Aside from his underperforming ball club, Brush had only the onset of health problems to contend with.69

When the expiration of the Players League and American Association yielded the bloated 12-team National League of 1892, Brush became the leader of the “Little Seven” (Baltimore, Brooklyn, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Louisville, St. Louis, and Washington) faction of club owners. While he quietly worked at achieving their ends, the public image of John T. Brush took frequent hits. A master of backroom intrigue with fellow owners but guarded and often uncommunicative with the Fourth Estate, Brush was neither loved by players nor admired by sportswriters. “Chicanery is the ozone which keeps his old frame from snapping, and dark-lantern methods the food that vitalizes his bodily issues,” intoned one critic.70 Impervious, Brush did not much care about bad press.

After outsider Andrew Freedman gained control of the New York Giants in early 1895, Brush made heavy-handed overtures toward buying Freedman out. The easily-offended Freedman, whose personal wealth vastly exceeded that of Brush, resented Brush’s presumption, and the two men quickly became antagonists in NL owners ranks. They even reportedly came to blows in the tap room of the hotel where NL winter meetings were held one year.71

While never becoming pals, Brush and Freedman developed a harmonious working relationship and collaborated on various fronts: elimination of syndicate club ownership; reduction of the National League to an eight-club circuit; the gutting of the American League Baltimore Orioles; the National Base Ball Trust scheme; the obstruction of AL efforts to place a team in New York, and lesser ventures.72 Thus, when Freedman’s interest in being a baseball club owner waned and he was ready to get out, Brush was his logical successor as boss of the New York Giants.73

On August 12, 1902, Brush assumed effective command of the New York Giants, appointed managing director of the club by president Freedman. Six weeks later, he was Giants boss in toto, having purchased Freedman’s majority interest in New York Giants stock for $200,000, a sum that Brush raised through sale of his Cincinnati Reds holdings to a consortium of local politicos.74 Shortly thereafter, Brush entrusted operation of his commercial interests in Indianapolis to son-in-law Harry Hempstead, and relocated to New Rochelle in suburban Westchester (New York) County, a short train ride away from the Polo Grounds. He also took up rooms at the Lambs Club, a show business social club situated on Broadway.

At the annual off-season meeting of the National Exhibition Company, Brush was formally installed as New York Giants president. Simultaneously, son-in-law Hempstead and Ashley Lloyd, Brush’s junior partner in the Cincinnati franchise and now a minority Giants shareholder, were elected to the club’s board of directors. With fiery manager John McGraw already in the dugout, a compliant corporate board in place, and an able, experienced chief executive at the helm, the fortunes of the last-place (44-88-5, .333) Giants were ready to skyrocket.

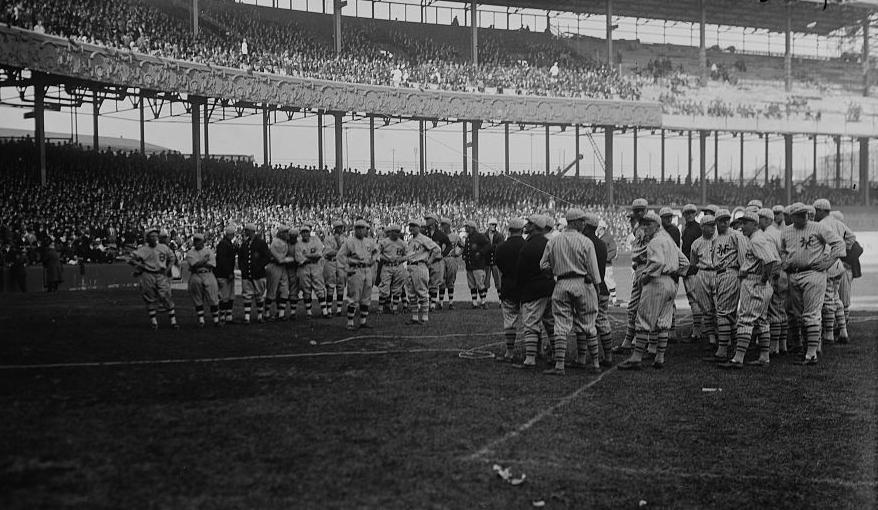

From 1903 through 1912, the New York Giants enjoyed great success: four National League pennants (plus a famous final game loss to the Chicago Cubs in 1908) and a 1905 World Series title amid a decade of first division finishes.75 All the while, John T. Brush, a noted stickler for decorous diamond behavior and previously the author of lampooned and unenforceable player conduct standards, privately reveled in the raucous on-field behavior of manager McGraw and his charges.76 Wisely, he gave McGraw a free hand regarding diamond strategy, player acquisition and salary, and involved him in other operational aspects of club-running. McGraw was also consulted on policy and business-related issues. Not only did the formula produce winning baseball on the field, attendance at the Polo Grounds soared. In 1908, the Polo Grounds gate of 910,000 represented triple the figure of the 1902 season, and set a new National League attendance record that would stand until 1920.

Manager John McGraw leads the New York Giants onto the field at the Polo Grounds in New York, circa 1911. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, BAIN NEWS SERVICE)

During the decade of Brush-McGraw collaboration, the only real concern was the club boss’s frailty. Starting in the early 1890s, Brush encountered increasingly serious health problems. More than once during his tenure as Cincinnati Reds president, he was not expected to survive. But John T. always managed to pull through. By the time he assumed command of the Giants, Brush, gaunt and usually grim-faced, looked well past his 57 years of age, and his use of his limbs had become limited. In time, he took to watching home games from the front seat of a chauffer-driven limousine parked deep along the right field foul line. Throughout these years, treatment of Brush’s condition was complicated by his refusal to take palliative but potentially-addictive medications. Often his pain was constant, and when accompanying the Giants on road trips, the intensely-disciplined club boss was given to playing solitaire through sleepless nights.77

As he came to grips with his approaching mortality, Brush had to deal with an unexpected crisis. On April 14, 1911, an early morning fire destroyed large portions of the 20-year-old Polo Grounds (nee Brotherhood Park). Brush wanted to rebuild the ballpark, replacing its charred wooden superstructure with modern construction materials, but had to weigh the costs (likely in excess of $100,000) against the future financial needs of his family. Surging Giants’ revenues made the money available, but Brush would not go forward with rebuilding plans unless wife Elsie approved. Happily for New York baseball, she did. And with New York Highlanders boss Frank Farrell magnanimously offering temporary use of Hilltop Park to the Giants, the 1911 season got off without a hitch. Two months thereafter, the Giants were back home, playing in a new iron-and-steel ballpark, the iconic bathtub-shaped Polo Grounds IV, and heading toward the 1911 National League pennant.

A National League flag in 1912 was John T. Brush’s last hurrah. As an accommodation to the visibly-failing Giants boss, the customary pre-World Series meeting of club representatives, officials, and league dignitaries was held at the Brush residence in New Rochelle where, among other things, Brush reconciled with American League president and longtime adversary Ban Johnson.78 Following a heart-breaking Giants loss to the AL champion Boston Red Sox, Brush presided over a hastily-convened meeting of the NEC board wherein Harry Hempstead was designated board chairman and club president-in-waiting. John T. then embarked upon a health-restorative railway trip to the West Coast. He never made it, dying outside Seeburger, Missouri on November 25, 1912. John T. Brush was 67. Baseball notables flocked to the Brush funeral in Indianapolis, none more grief-stricken than pallbearer John McGraw. “A gamer, braver man never lived,” said McGraw.79

The Hempstead Regency

The beneficiaries of the Brush will were his widow Elsie and daughters Eleanor and Natalie, each of whom was bequeathed a one-third share of the Brush estate. The estate holdings included the clothing business in Indianapolis and real property, but its principal asset was majority ownership of the New York Giants. The year before Brush’s death, Helene Britton had blazed the trail of female stewardship of a major league ball club, inheriting control of the National League St. Louis Cardinals upon the death of her bachelor uncle, Stanley Robison. Thereafter, Mrs. Britton took an active role in the management of Cardinals’ affairs. But the Brush family women had no interest in running the Giants. Nor would a man as tradition-minded as John T. Brush have wanted them to.

The beneficiaries of the Brush will were his widow Elsie and daughters Eleanor and Natalie, each of whom was bequeathed a one-third share of the Brush estate. The estate holdings included the clothing business in Indianapolis and real property, but its principal asset was majority ownership of the New York Giants. The year before Brush’s death, Helene Britton had blazed the trail of female stewardship of a major league ball club, inheriting control of the National League St. Louis Cardinals upon the death of her bachelor uncle, Stanley Robison. Thereafter, Mrs. Britton took an active role in the management of Cardinals’ affairs. But the Brush family women had no interest in running the Giants. Nor would a man as tradition-minded as John T. Brush have wanted them to.

The terms of the Brush will entrusted disposition of estate assets, including the Giants, to co-executors Harry Hempstead and Ashley Lloyd. Immediately after the Brush funeral, Hempstead quelled rampant speculation about an imminent sale of the ball club. The New York Giants would remain in the possession of the Brush family, he informed the press.80 Then, as foreordained by his late father-in-law, Hempstead took over superintendence of the Giants, installed as corporation chairman and club president at the January 1913 NEC board meeting. A quiet, honorable man of sound but cautious judgment, Hempstead would administer the franchise capably, but with a constant eye upon what was in the best interest of the Brush heirs. Regrettably, his risk-averse temperament and lack of vision proved costly. In January 1919 and over the dissent of his wife Eleanor, Hempstead relinquished a controlling interest in the New York Giants franchise to a syndicate headed by Manhattan stock trader Charles A. Stoneham. In so doing, Hempstead deprived the family of the financial windfall that attended baseball club ownership during the Roaring Twenties.

Franchise regent Harry Newton Hempstead was born in Philadelphia on June 25, 1868. He was the youngest of six children born to the head of a customs brokerage firm, and grew up in comfortable circumstance. Although Lafayette College-educated to be a chemist, Harry began his working life as an executive in a New York City freight hauling company. Thereafter, he met and began courting Eleanor Gordon Brush, the daughter of [then] Cincinnati Reds owner John T. Brush. The couple married in October 1894, some four months after John T. had taken 24-year-old stage actress Elsie Lombard as his second wife.81 In 1898, the Hempsteads relocated to Meadville, Pennsylvania, where Harry assumed the presidency of the Garfield Chewing Gum Company. Four years later, Hempstead’s acceptance of day-to-day oversight of the When Store operation in Indianapolis freed his father-in-law to remove himself to New York and focus his attentions on the fortunes of the Giants.

Although no stranger to the game – Harry Hempstead had played outfield for prep school and college nines in his younger days82 and was a ten-year member of the New York Giants’ corporate board – the successor of the renowned John T. Brush was a blank to most baseball fans. The Cincinnati Enquirer informed readers that the new Giants boss was “a young man of engaging personality and quiet business temperament … [who had been] a careful and quiet student of the game for many years.”83 The New York faithful were reassured by news that John McGraw would continue as Giants manager, signed to a new $30,000 per year contract.84 And Hempstead would continue the Brush policy of giving McGraw free reign over game strategy and personnel moves. But unlike his predecessor, Hempstead did not seek McGraw’s advice on larger matters, like franchise direction and business outlook. Here, Hempstead relied on the counsel of minority owner/treasurer Ashley Lloyd and club secretary John B. Foster.85

An early order of business for the fledgling administration was reciprocating a kindness extended two seasons before by the American League New York Highlanders. When the junior circuit rival lost their leasehold on Hilltop Park at the close of the 1912 season, Hempstead promptly made the Polo Grounds available. For the next decade, the renamed New York Yankees would call the Polo Grounds home – while depositing $50,000 per annum rent into Brush family coffers. The accommodation also ushered in an era of cordial relations between the two New York clubs that would last the duration of the Hempstead regime.

The new club order began successfully, with the Giants winning a third-consecutive National League pennant in 1913, only to lose a third-consecutive World Series to an American League foe, in this instance, the Philadelphia Athletics. But trouble in the form of the upstart Federal League soon emerged. Although Hempstead would usually be a listener rather than a talker at NL owners’ conclaves, he was prompt to sound the alarm about the outlaw league, the peril posed by the Federals driven home to Hempstead when its backers inadvertently solicited him to invest in their Indianapolis franchise.86 To reduce player receptivity to Federal League inducements, Hempstead persuaded fellow NL magnates to concede certain contract-related demands recently made by the players, a strategy subsequently rewarded by the loyalty of Christy Mathewson and other Giants stalwarts when the FL came calling.

While generally perceived as a genial, mild-mannered man, Hempstead had a cold, clear eye when it came to business – as his fellow club owners and league officials would discover in early 1915. With the financially strapped International League franchise in Jersey City likely to be bankrupted by competition from the FL champion Indianapolis club just relocated to Newark, the leaders of Organized Baseball proposed to save the Jersey City club by moving it to the Bronx for the 1915 season. Such a placement, however, required the permission of the New York Giants, which held territorial rights over the borough. But Harry Hempstead would not grant it. In his view, another professional baseball club playing in New York City was not in the best interests of the Brush family. Notwithstanding pointed criticism by American League president Ban Johnson, International League boss Ed Barrow, and The Sporting News, Hempstead would not yield. The Jersey City club stayed put.87 Months later, the Federal League got a similar dose of Harry Hempstead, the steely businessman. The Federals’ plan to place a team in Manhattan was quietly but neatly thwarted by the Giants boss. In a move reminiscent of Andrew Freedman in his heyday, Hempstead dispatched agents to scoop up the East Side Manhattan building lots that had been designated as the site of the FL club’s ballpark, thereby depriving the would-be interlopers a place to play.88

The rational, business-first side of Hempstead was next put on display after the Federal League expired after the 1915 season. Although Organized Baseball had emerged triumphant in the battle with the Federals, a fearful toll on the game’s wellbeing had been extracted, in Hempstead’s opinion. Citing calculations made by NL officials, Hempstead observed that the minors had contracted from 49 leagues in 1913 to 26 presently, while more than 5,000 former players had lost their place in professional ranks, all of which Hempstead attributed to the havoc caused by the conflict with the outlaw circuit. “The man who thinks wars are good for baseball has never had anything to do with a club in a time of war,” he declared.89 That outlook propelled the “affable and likeable” Giants president to “the center of one group of good souls” who urged reconciliation with Federal League backers during a post-war parley of NL/AL/FL principals.90

One such backer was Harry F. Sinclair, the swashbuckling oil tycoon who had owned the FL Newark Peppers. In the winter of 1915-1916, Sinclair set his sights on acquisition of the New York Giants. Soon, rumors abounded. When queried on the subject, Hempstead – ever the businessman – revealed that “while he had received no definite offer for the club, he would sell [the Giants] if the offer was alluring.” Moreover, “he was open to proposals.”91 But a prospective sale foundered when Sinclair declined to meet the reported Hempstead asking price of $2 million for the New York club, an amount that Sinclair deemed “beyond all reason.”92 For the time being, therefore, the franchise would remain in the hands of the Brush family.

Unlike his predecessor, Hempstead was not fixated on baseball. During his tenure as Giants president, he continued oversight of Brush family business operations in Indianapolis, served as a trustee of his alma mater, Lafayette College, and enjoyed winter sporting activities in Lake Placid.93 But tending to the Giants was never too far from his mind. The 1917 season brought a second National League pennant to the Hempstead administration, but things had not gone agreeably. Manager McGraw had become resentful of his diminished role in franchise operations, and relations between him and Hempstead grew more distant. The Giants roster also contained personality types, particularly contrary second baseman Buck Herzog, not to the club president’s liking. When Herzog refused to accompany the club on a late-season trip to Boston, Hempstead suspended him. Buck was reinstated in time to play in the World Series, but the results were another Giants disappointment: a loss to the Chicago White Sox in six games.

A more long-term concern of Hempstead was the effect that American entry into World War I was having on baseball. Although the 1917 season had not been seriously affected by the war effort, 1918 would prove a different matter. Player ranks were thinned by the call to military service or to work in defense industries, the regular season abbreviated, and the Fall Classic hurriedly completed by September 11. All the while, attendance at Giants games plummeted. The gate for 1918 home games was only 256,618, barely half that of the previous season and more than 400,000 below the inaugural 1913 campaign of the Hempstead administration. The major leagues as a whole had fared no better in 1918, each circuit losing more than one million patrons from the previous year. Drastic measures were needed to restore the game to good health. To that end, Hempstead and new Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee proposed the installation of former US President William Howard Taft as an all-powerful one-man executive-in-charge of the major leagues.94 While respectfully received, the Hempstead-Frazee proposal went nowhere.

Professional baseball was on the verge of a golden era. The game would enjoy immense popularity in the 1920s, with ballpark attendance skyrocketing and club investors reaping the rewards. But Harry Hempstead did not see this. In January 1919, Hempstead saw only hard times ahead, with baseball being no place for the Brush family women and their money. His determination to sell the ball club, however, created a split in family ranks. Elsie Brush trusted Hempstead’s judgment and would do as he advised, while daughter Natalie, although now a young adult, would do what her mother told her. Eleanor Hempstead was another matter. A private woman who shunned the limelight, she had inherited her father’s business acumen and was fiercely protective of his legacy.95 To Harry’s chagrin, Eleanor would not sell her interest in the club. Nor would minority club owner Ashley Lloyd part with his Giants holdings. Still, Hempstead managed to cobble together a block of club stock sufficient to constitute a majority interest in the New York Giants franchise.

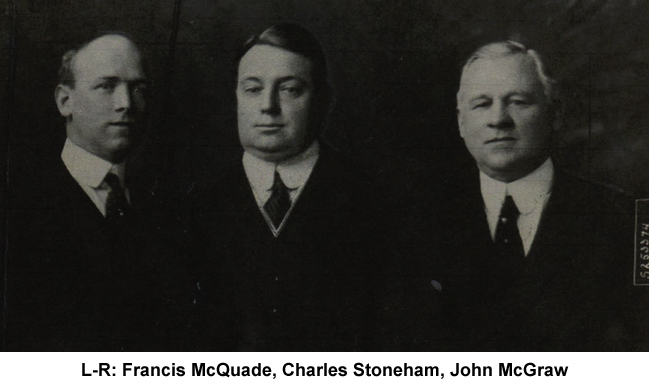

On January 14, 1919, Hempstead released a public statement announcing that “with many regrets,” the Brush family had sold the New York Giants. The new club owners were a syndicate headed by Manhattan stock trader Charles A. Stoneham. Giants manager John McGraw and New York City magistrate Francis X. McQuade were small-stake syndicate members and would become club officers, as well. The sale price was generally reported as $1 million.96 Although Eleanor Hempstead and Ashley Lloyd would retain their stakes in the club into the mid-1920s, the guard at the Polo Grounds had changed.97

The Stoneham Syndicate

In the early 1920s, the New York Yankees began the assembly of a professional sports dynasty, with many pundits rating the 1927 Yanks the best ballclub in major leagues history. Yet during the first half of the decade, the New York Giants outdid their local rival. Piloted by John McGraw and with a lineup featuring future Hall of Famers Frankie Frisch, George “High Pockets” Kelly, Dave Bancroft, and Ross Youngs, the Giants captured four consecutive National League pennants (1921-1924) and two World Series crowns, both taken at the expense of the Yankees. Remarkably, these feats were accomplished despite a fractious and oftentimes dysfunctional front office. At the center of the turmoil was one of baseball’s more improbable figures: club president Charles A. Stoneham.