August 10, 1939: Exhibition against minor-league namesake turns into rout for St. Louis Browns

Dating to the nineteenth century, the city of Youngstown, Ohio, had always been a stop for semipro or minor-league baseball teams.

Dating to the nineteenth century, the city of Youngstown, Ohio, had always been a stop for semipro or minor-league baseball teams.

In 1885 it was part of the short-lived Iron & Oil League. In the early 1900s, the Ohio Works—named for the U.S. Steel mill in the city—played in the Ohio-Pennsylvania League. Central League entrants included the Tubers (named for another steel company, Youngstown Sheet & Tube) and the Buckeyes.1

In 1939 Youngstown got a new minor-league franchise, a Middle Atlantic League affiliate of the St. Louis Browns. The Class C team, managed by Billy Urbanski in what turned out to be his final year in pro baseball,2 was forced to relocate from Johnstown, Pennsylvania, because of poor attendance, and its arrival in the Mahoning Valley, Youngstown’s home area, was not greeted with unbridled enthusiasm. “The club coming here now was tossed our way because the St. Louis Browns need a farm [team], and there doesn’t seem to be any better place to put this particular item of it,” the Youngstown Vindicator commented.3

But fans warmed quickly to the new team, which played its home games at Idora Park, an amusement park built at the end of a trolley line on the city’s south side. The team drew well, and as a gesture of goodwill, the parent Browns scheduled an exhibition on August 10, an open date between a two-game series in Cleveland4—both Indians wins—and a weekend three-game set in Detroit. The Browns had won only 29 of 100 games, giving them the worst record in the American League.

The Youngstown Browns were also on a two-game skid, having lost their previous games to Charleston. The Vindicator noted that although many other major-league teams and players had played at the field in the shadow of the Jack Rabbit, one of Idora Park’s two roller coasters, it was the first time the Browns had come to Youngstown.5

Prices for tickets were reasonable—higher than a standard Mid-Atlantic game, but lower than other exhibitions played at Idora Park—and the Vindicator noted that a large crowd was expected, with all the box seats sold out a week before the game, and many reserved seats gone as well. The crowd was estimated at around 4,200.6 Prior to the game, first-year St. Louis manager Fred Haney had said there would be no letting up. And indeed, no quarter was given.

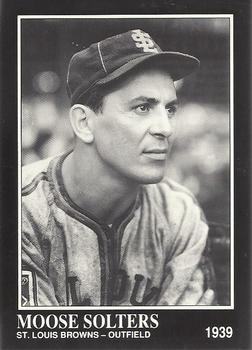

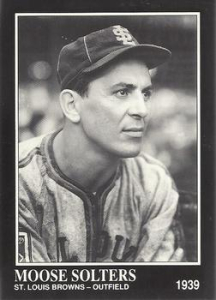

Moose Solters, in the second stint of his career with St. Louis after being claimed off waivers from the Indians the week before, opened the game’s scoring, doubling to left-center field in the top of the second, then taking third on a wild pitch before scoring on a sacrifice fly by Harlond Clift.

St. Louis’s lead was short-lived. In the bottom of the second, center fielder Pete Kraus walked and right fielder Freddie Reinhart hit a home run off St. Louis starter John Whitehead to give Youngstown a 2-1 lead.

In the fourth, Youngstown pitcher Fred Sanford got into a jam after Solters singled and Clift walked. But Billy Sullivan Jr. and Hal Spindel were retired, thanks to fancy defense by shortstop Floyd Baker and first baseman Paul Amen.7

In the top of the fifth, St. Louis rookie Johnny Berardino—who would become better known as an actor than as a baseball player—led off the inning with a home run over the left-field fence, knotting the score at 2-2.

Berardino hit another pitch in the sixth inning for what the Vindicator described as a sure Texas League single, but Baker made a running catch, and then doubled Sullivan off second base to end the St. Louis threat.

But Sanford’s luck could only hold up for so long, and St. Louis took the lead for good in the top of the seventh. Mark Christman singled, then came home on a double by Joe Grace.

The floodgates opened in the top of the eighth. Clift singled to lead off the inning, and Chet Laabs—who’d replaced Sullivan after he twisted his ankle trying to get back to second on Baker’s double-play grounder in the sixth—struck out swinging. Spindel and Berardino walked to load the bases. Myril Hoag, batting for Whitehead, hit a bases-clearing double to center field, giving St. Louis a 6-2 lead.

Christman walked and then was put out at second base as Hoag advanced. George McQuinn doubled to right, scoring Hoag, and that was the end of the night for Sanford. Youngstown brought in Tony Klisan, who walked Solters but got Clift to fly out to left to end the four-run inning.

In the bottom of the eighth, Hoag came on to pitch in relief. The Vindicator noted that he aspired to a regular pitching job, and “had plenty of stuff on the ball, but wasn’t overburdened with control.”8 He walked Klisan and gave up back-to-back singles to Amen and Krause, scoring Klisan, who came out again in the ninth to pitch for Youngstown.

Klisan fared little better than Sanford the previous inning, walking Sullivan and Spindel on eight pitches. Berardino cracked his second home run of the night. Hoag flied out, and Christman walked. Grace struck out for the second out of the inning, but McQuinn got a hit and Solters walked to load the bases. Klisan was then lifted in favor of Ralph Sams, who gave up a two-run double to Clift and a two-run single to Laabs. Spindel walked, and Berardino flied out to end the inning with St. Louis holding a 14-3 lead.

Youngstown went down without a fight in the home half of the ninth, and the Browns were on the move. They were headed downtown to the Erie Railroad Station, with two special charter sleeping cars for an overnight trip to Detroit.

St. Louis finished 1939 with a 43-111-2 record, the worst in the majors. The Youngstown affiliate fared a little better, finishing in seventh place with a 60-70 record. The Youngstown Browns continued for two more seasons, but did not field a team in 1942, the last year before the league was suspended during World War II. After the war, Youngstown held a spot in the Mid-Atlantic League—although it was no longer a Browns affiliate—until shortly before the league folded in 1951.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for pertinent information, including the box score and play-by-play.

Notes

1 Charles A. Landolf, “Youngstown Once Main Link in Minor Loop Baseball Chain,” Youngstown Vindicator, April 1, 1977: 26, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=pqgf-8x9CmQC&dat=19770401&printsec=frontpage&hl=en.

2 Urbanski also played in 55 games, 51 as shortstop. He inserted himself late in the exhibition against St. Louis, going hitless.

3 Sean T. Posey, Hidden History of Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley (Charleston, South Carolina: History Press, 2022), 26.

4 The series comprised one game at Cleveland Stadium, and one at League Park.

5 Frank B. Ward, “St. Louis Browns Oppose Youngstown Browns in Exhibition Tilt Here Tonight,” Youngstown Vindicator, August 10, 1939: 15. The story noted the connection between the Browns and Youngstown through former manager Jimmy McAleer, a native of the city.

6 George M. Vincent, “St. Louis Browns Trample Youngstown 14-3 as Pitching Falters Late in Game,” Youngstown Vindicator, August 11, 1939: 14.

7 Baker ended up marrying a Youngstown woman and lived near Idora Park until his death in 2004. From 1943 to 1955, he played for the Browns and four other major-league teams. Amen never made the majors, but spent a decade as the baseball coach at the US Military Academy and later coached football at Wake Forest.

8 “St. Louis Browns Trample Youngstown 14-3 as Pitching Falters Late in Game.” Hoag made one pitching appearance for the Browns that season and two for the Indians in 1945—the extent of his major-league pitching career.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Browns 14

Youngstown Browns 3

Idora Park

Youngstown, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.