September 30, 1880: Amateur Charlie Guth wins in only professional appearance for White Stockings

When Charlie Guth took the mound on September 30, 1880, as a surprise starter for the Chicago White Stockings, the game was of little consequence. With the possibility of an uneven number of games being completed by National League members, league standings were determined by the winner of the most contests (this was true prior to 1883), and the White Stockings had already amassed 66 wins to easily outdistance second-place Providence, which would claim 52 victories by season’s end.

When Charlie Guth took the mound on September 30, 1880, as a surprise starter for the Chicago White Stockings, the game was of little consequence. With the possibility of an uneven number of games being completed by National League members, league standings were determined by the winner of the most contests (this was true prior to 1883), and the White Stockings had already amassed 66 wins to easily outdistance second-place Providence, which would claim 52 victories by season’s end.

During its dominant season, Chicago had relied on the arms of Larry Corcoran and Fred Goldsmith, with the duo combining for 84 of the team’s 86 starts and 64 of its 67 wins. At this juncture, Corcoran had started the prior three games, with the September 29 outing using both pitchers and a catcher to complete an embarrassing 19-10 shellacking at the hands of the Buffalo Bisons. The Chicago Tribune account of the game was pointed and unforgiving:

“They (Buffalo) struck the Chicagos in a particularly crippled condition, with both pitchers suffering from lame arms, and two possible catchers occupying seats in the grand stand. Moreover, (Chicago catcher King) Kelly’s hands were very sore, and neither Corcoran nor Goldsmith dared to put on a curve or speed. The result was that their pitching was the softest kind of ‘pie’: there are a hundred amateurs in Chicago who could have pitched a better game.”1

Apparently, the White Stockings’ management was listening.

By 1880, future Hall of Famer Albert Spalding had left his playing days behind. After retiring, Spalding had become secretary of the White Stockings while also leading a sporting-goods business founded with his brother Walter in 1876. His position as secretary afforded him some influence with Chicago manager Adrian Constantine “Cap” Anson, and among Spalding’s employees was the 24-year-old Guth, a noted amateur baseball player, at that point toiling for the Chicago Lake Views.2

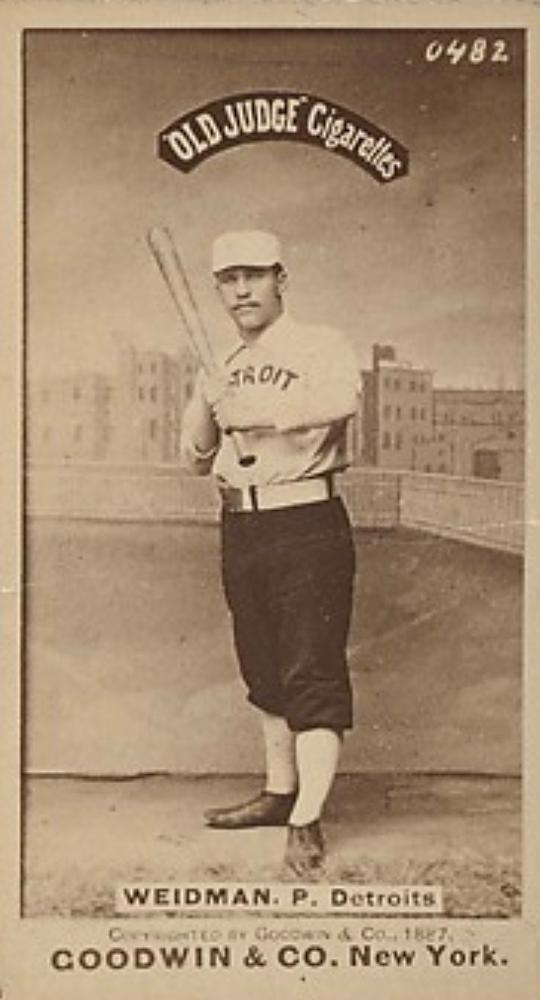

Buffalo, in seventh place entering the day, had little to gain with either a win or loss, so it started George Edward “Stump” Weidman, who was saddled with a 0-8 record while toiling in his first season in the National League. Stump was the backup pitcher to future Hall of Famer James Francis “Pud” Galvin, who had posted 20 victories among his 54 starts for the season. With a season total 24 wins, the Bisons were mired in seventh place, and the outcome would have no bearing on their finish.

The game was hosted at White Stocking Park, otherwise known as Lake Front Park. Located near the corner of Michigan Avenue and Randolph Street by the tracks of the Illinois Central Railroad, it was the second iteration of Lake Front Park. The original opened in 1871 but perished in the Great Chicago Fire on October 8 of that year.

After completing the season at the Union Grounds and subsequently using the 23rd Street Park from 1872 to 1879, the White Stockings returned to the new Lake Front Park in 1878 and occupied the space until 1884, when it was determined that the land was actually owned by the federal government and the City of Chicago had no authority to lease the property, “it being the intention to dedicate the said public grounds irrevocably to the use of the public,” as it was “public grounds forever to remain vacant of buildings.”3

Spalding, by this point president of the club, was later forced to vacate the park in 1885, a space that became part of Chicago’s Grant Park (renamed in 1901) which hosted a significant amount of the estimated five million people who attended the Chicago Cubs’ 2016 World Series celebration.

Before that happened, Charlie Guth seized his own moment in history.

It is unknown whether Guth was right-handed or left-handed, as a play-by-play account of the game does not exist, and limited press coverage outlined events of the day.

The host White Stockings chose to bat first. Chicago’s top three in the batting order – Abner Dalrymple, George Gore, and Kelly – were 9-for-15 in the game, and they were credited with igniting a three-run first that staked Guth to an early lead.

As noted in the Chicago Tribune’s account of the game: “Chicago’s runs were the product of magnificent batting by Dalrymple, Gore, and Kelly, aided by hits at the right time by Anson, (Tom) Burns and (Larry) Corcoran.”4

Buffalo tallied a run in the bottom of the inning. With two outs, left fielder Jack Rowe registered his only hit of the game, and came around to score an unearned run on successive errors by Burns, Gore, and Kelly. The run was Guth’s only blemish for most of the game.

The Chicago Tribune: “(Guth) provided to be an entire success for seven innings, during which time the Buffalos earned first base but once. He has all the elements of a first-class pitcher, unless it be experience, coolness, and nerve, which only come with time. His variations of curve and speed are extremely puzzling.”5

Chicago added seven more runs through the middle innings to take a 10-1 lead. The Chicago Daily Telegraph noted that “the Chicagos piled up nine runs off Weidman, seven of them earned. They added another to the score in the eighth when Galvin was pitching.”6

It was the bottom of the eighth before Guth showed any vulnerability.

“If he had maintained his pace throughout the game, he would have proved a phenomenal success, but he weakened visibly in the eighth inning, and then became wild and unsteady,” the Tribune reported.7

Bill Crowley led off the bottom of the eighth inning for Buffalo with a double and advanced to third on a wild pitch. A single by Hardy Richardson scored Crowley, and Richardson took third when Dalrymple let the ball get by him. Rowe hit a hard smash to second baseman Joe Quest, and Richardson was called out on Quest’s throw to the plate. Standing at first base, Rowe scored on three successive wild pitches by Guth. A final run in the inning came on Galvin’s single after hits by Joe Hornung and Mike Moynahan. The score was 10-4 entering the final inning.

Chicago went scoreless in the ninth, leaving an obviously fatigued Guth to close out the victory.

He struggled, as the Chicago Tribune noted: “In the ninth a double by Stearns, a three-baser by Richardson, and singles by Crowley, Hornung and Moynahan, together with a fumble by Quest, gave four runs, one being earned, and it looked for a time as though the game was going to be won before the side could be got out, but Corcoran made a high jump on Force’s bounder, and threw him out at first.”8

Likewise, the Chicago Daily Telegraph noted, “The Buffalo made seven of their runs in the last two innings, when they batted Guth’s weakened delivery all over the field.”9

Despite faltering late, the 24-year-old Guth earned the win in his only professional baseball appearance. His employment with Spalding qualified him to take a similar position with Wright & Ditson in Boston, and he relocated in late 1882 or early 1883, but died shortly thereafter at age 27 from asthenia, described as a general weakness or loss of strength.

The 10-8 victory was number 67 for Chicago, as they captured the first of three consecutive National League titles, this one by a margin of 15 games.

Chicago and Buffalo played two exhibition games in the following days, testing a new square bat, as well as a new baseball design. But with no World Series until 1903, those games had no bearing on the White Stockings’ championship.

Some additional noteworthy facts about the contest:

- Lake Front Park (sometimes referred to as Lakefront Park) had the shortest outfield fences in the majors, ever.10 Left field stood 186 feet from home plate and right field was a mere 196 feet. Despite the short distances and the pitching of the amateur Guth for Chicago and inept starter Weidman for the Bisons, there were no home runs recorded in the contest.

- In addition to Spalding, the game featured three additional future Hall of Famers in Cap Anson (1939) and King Kelly (1945) for Chicago and Pud Galvin (1965) for Buffalo. Charles Gardner “Old Hoss” Radbourn, listed as an outfielder and second baseman on the Buffalo roster, played in six games for Buffalo early in the season, but the Bisons released him in May. He became a pitcher in 1881, winning 59 or 60 games in 1884 (accounts differ) and was ultimately part of the 1939 Hall of Fame class with Anson.

- George H. “Foghorn” Bradley was the umpire of record. He previously pitched for Boston for a portion of the inaugural National League season in 1876 but his playing career was of limited duration, much like Guth’s. Despite winning nine games in 21 starts, he was deemed expendable by the Red Stockings and never returned to the major leagues as a pitcher. He did enjoy a solid career as an umpire, later referred to as “one of the best umpires in the country” and noted for his “powerful and penetrating voice.”11

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Bruce Slutsky and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org for pertinent information.

Notes

1 “Tremendous Batting Performance of the Buffalo Team Yesterday,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1880: 8.

2 “The Game Is Up,” Chicago Daily Telegraph, October 1, 1880: 1.

3 “The Lake Front,” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1884: 8.

4 “The Chicagos Finish the League Season with a Victory Over Buffalo,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1880: 8.

5 “The Chicagos Finish the League Season with a Victory Over Buffalo.”

6 “The Game Is Up.”

7 “The Chicagos Finish the League Season with a Victory Over Buffalo.”

8 “The Chicagos Finish the League Season with a Victory Over Buffalo.”

9 “The Game Is Up.”

10 “White Stocking Park,”, https://www.seamheads.com/ballparks/ballpark.php?parkID=CHI03, accessed October 11, 2022.

11 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, May 23, 1886: 11.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Stockings 10

Buffalo Bisons 8

White Stocking Park

Chicago, IL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.