April 19, 1894: Dan Brouthers and upstart Orioles stun heavily favored Giants on Opening Day

When Ned Hanlon became manager of the Baltimore Orioles in May of 1892, the team was a dysfunctional group largely composed of insubordinate and unmotivated players. They finished in last place in the 12-team National League, losing 101 games, and that was an intolerable situation for Hanlon, a man who hated to lose.

When Ned Hanlon became manager of the Baltimore Orioles in May of 1892, the team was a dysfunctional group largely composed of insubordinate and unmotivated players. They finished in last place in the 12-team National League, losing 101 games, and that was an intolerable situation for Hanlon, a man who hated to lose.

He immediately began making changes to his roster and orchestrated a series of shrewd moves that made him a feared trader and earned him the sobriquet Foxy Ned. He obtained unheralded players such as Joe Kelley, Hughie Jennings, Steve Brodie, and others who became stars under his tutelage.1 By the end of his first full season in 1893, he had retained only three players who were on the team he inherited: Wilbert Robinson, Sadie McMahon, and John McGraw. The Orioles came in eighth and improved their winning percentage by nearly 150 points over 1892.

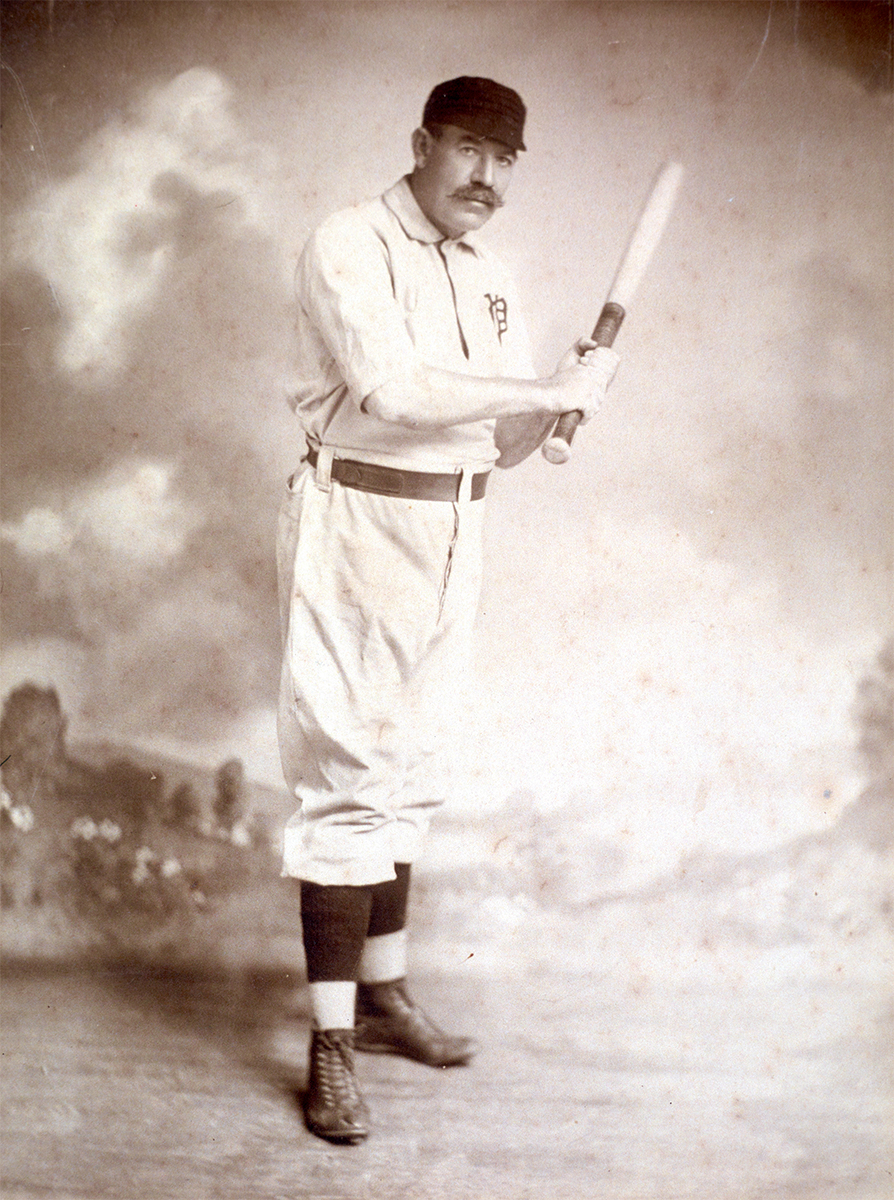

Hanlon further enhanced his reputation as a judge of talent when he obtained Willie Keeler and Dan Brouthers in a trade with Brooklyn in the 1893-94 offseason. McGraw called it “the greatest trade ever made by Hanlon, and he made many.”2 Hanlon now had a team of young players3 who had a burning desire to win and were dedicated to playing the game the way he envisioned: “Baseball as she is played,” he called it.4

In the spring of 1894, Hanlon ran one of the most innovative training camps in baseball history. During the day he worked his players hard, instructing them in the tactics and strategies of what was known as “Inside,” or “Scientific” baseball. He drilled them repeatedly on the hit-and-run play, baserunning, precision bunting, reading outfielders’ body positions in order to take an extra base on hits, and much more.5 In the evenings, the players met in his room where he distributed copies of the rules and they discussed the tactics of the game.6 He emphasized the importance of teamwork, and encouraged them to think and “always keep the other fellows guessing and work in the unexpected at the most critical time.”7

Despite the improvement shown by the Orioles in 1893, Chicago Colts player-manager Cap Anson expressed what most baseball people thought about Baltimore: “The team will probably play good, lively ball, but will hardly be in the struggle for the pennant.”8 But the baseball world would be stunned, for Hanlon had convinced his players that they were a tactically superior team to any in the League and that they could beat anyone.

Star player-manager John Montgomery Ward and his New York Giants arrived the evening before Opening Day at the Eutaw House in Baltimore, and Ward was asked by reporters what he thought of his team’s chances against the Orioles. He told them he would be satisfied with winning two, but privately said he expected to gain a sweep.9 Later, Ward visited his old friend Hanlon at the Orioles’ headquarters, where they complimented each other’s teams and then amiably “wished each other mutual misfortune.”10 The Giants had finished fifth in the NL in 1893, seven games ahead of the Orioles.

The next day three special train cars carrying Giants fans, many toting foghorns, arrived. They were in a “jolly humor” and expected to see their team easily sweep the “poor little Orioles.”11 They were shuttled to the Eutaw House, which was filled with people “gazing at the New York players with awe and reverence.”12

When the Orioles arrived after their morning practice, where Hanlon had given them “some final words of counsel,”13 the press, players, and guests assumed their places in a parade that meandered through the city on its way to Union Park. Great throngs of people gathered all along the route, wildly cheering their heroes.

At the ballpark “the wildest confusion reigned,” and when all the seats had been sold, fans seeking general admission overwhelmed the ticket sellers. The overflow crowd poured into the outfield, where policemen spread them out behind ropes. In the grandstand the raucous crowd made the stands tremble, much to the consternation of those in the upper levels.14 Hundreds of people without tickets climbed telegraph poles and trees and onto rooftops to watch the game.15

As game time approached, Ward won the coin toss and he chose to have the Giants bat in the bottom of the first.16 The largest crowd ever gathered to watch a baseball game in Baltimore, more than 15,000 fans,17 rippled with excitement as umpire Tom Lynch called “Play Ball!” and John McGraw stepped to the plate to face Giants fireballer Amos Rusie. He hit a sharp liner that left fielder Eddie Burke made a great effort to catch, but dropped,18 and Keeler hit a groundball that shortstop Yale Murphy could not handle.19 Rusie, however, retired the next three batters.

The Giants were held scoreless in their half of the inning. Neither team scored in the second, and in the bottom of that inning, Keeler made a spectacular catch in right, nimbly jumping over the rope holding back the crowd, which scrambled to get out of his way.

In the third McGraw walked and stole second, and when catcher Duke Farrell’s throw sailed into center field, Ward blocked McGraw from advancing. An angry McGraw threw a punch at Ward, who responded with “something very choice to the fresh young pug, as the glaring looks on both sides showed.”20

A reporter for Sporting Life was outraged by McGraw’s behavior in this incident, and others in the season-opening series, and wrote that “he is too hot tempered to be allowed around without a guardian.” He wrote that McGraw’s actions toward Ward were “uncalled for and a disgrace to the great crowd that saw the game.” He added, “These tough mugs who want to fight on all occasions, and who use foul language at the slightest provocation, should be chased out of the business.”21

After the McGraw-Ward flareup subsided, Keeler struck out but reached safely when Farrell dropped the third strike and threw wide to first. McGraw advanced to third. Brodie’s grounder forced out Keeler, but McGraw scored the game’s first run. Brodie stole second22 and moved to third on a groundout by Brouthers. With two out, Kelley grounded to third baseman George Davis, whose throw was dropped by Roger Connor at first, and Brodie scored for a 2-0 lead.

In the fifth, Keeler walked and took second on Brodie’s single. Brouthers’ ground-rule double over the heads of the crowd in center field scored Keeler and placed Brodie on third. Brodie scored on a fly ball and second baseman Heinie Reitz singled to score Brouthers. In the Giants’ turn, they scratched out a run when right fielder Mike Tiernan singled, stole second, and scored on two successive sacrifices. But the one run did not satisfy Giants fans, and they became noticeably subdued.23 The sound of their tin horns had abated and Baltimore fans began to taunt them by asking, “What’s the matter with the horns?”24

The Orioles escaped a bases-loaded threat in the sixth, and the score remained 5-1 until the eighth, when Robinson singled and advanced to third on McGraw’s single. Keeler doubled home Robinson and McGraw went to third. Brouthers then delivered the most impressive hit of the game. His drive over the heads of the crowd in center hit the 16-foot-high wall three feet from the top. McGraw and Keeler scored to give the Orioles an 8-1 lead.

In the bottom of the inning, Ward reached on a force and George Van Haltren walked. Ward stole third and scored on Tiernan’s sacrifice, and Van Haltren scored on Davis’s single. No further runs were scored, and when the final out was recorded in the ninth, “one grand sigh of relief burst forth” from the Baltimore fans, and a horde of people scrambled onto the field to congratulate the Orioles, who had to fight their way to the clubhouse.25

The Orioles had executed some of the tactics and strategies that they had worked on in spring training. Hanlon’s team had five sacrifice hits and four stolen bases, and played excellent defense. While Hanlon complimented his players “as a whole and individually,” for “their steady work,”26 Ward complained that the tactics used by the Orioles was “trick stuff by a lot of kids.” He added, “I’m not sure what they are doing is legal. As soon as we get to Washington, I’ll ask Nick Young, the League president, about it.”27

It is unclear what Ward considered to be trick stuff, but McGraw recalled nearly 30 years later that Ward “acknowledged that we had really pulled something new in baseball.”28 McGraw added, “That one series made the Orioles. Seeing that our stuff had worked, we were full of confidence and cockiness.”29

The Orioles swept the three-game series and put the League on notice that they were a team to be reckoned with in 1894. Throughout the season, they continued to refine and develop their teamwork-centered tactics and strategies. Moreover, with the actions of McGraw in particular, the team’s infamous reputation as one of the more rough and rowdy teams in the National League continued to grow.

The Orioles went on to win three straight pennants and become one of the most influential and colorful teams in baseball history, and it all began on Opening Day in 1894.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Gary Belleville and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Tom Delise and Jay Seaborg, Foxy Ned Hanlon: The Baseball Life of a Hall of Fame Manager (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2024). Specific game details are from the Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1894; the New York Sun, April 20, 1894; the New York Times, April 20, 1894; and the New-York Tribune, April 20, 1894.

Photo Credit

Dan Brouthers, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Notes

1 Hanlon also has an impressive coaching tree. Of his players who later became major-league managers, seven of them won a total of 32 pennants and 12 World Series championships. These seven are John McGraw, Hughie Jennings, Wilbert Robinson, Connie Mack, Fielder Jones, Miller Huggins, and Kid Gleason.

2 John McGraw, My Thirty Years in Baseball (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1923), 67.

3 According to baseball-reference.com, the Orioles position-player group in 1894 was the youngest in the league at 25.8 years old. They had the second oldest pitching staff at 26.5.

4 Lyle Spatz, Willie Keeler: From the Playgrounds of Brooklyn to the Hall of Fame (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015), 36.

5 Bill Felber, A Game of Brawl: The Orioles, the Beaneaters & the Battle for the 1897 Pennant (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 11-12.

6 Burt Solomon, Where They Ain’t: The Fabled Life and Untimely Death of the Original Baltimore Orioles, The Team That Gave Birth to Modern Baseball (New York: The Free Press, 1999), 60.

7 Spatz, 35.

8 “Anson’s Estimate of Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1894: 6.

9 Solomon, 64.

10 “Captain Ward Arrives,” Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1894: 6.

11 “New York Enthusiasts,” Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1894: 6.

12 “Baseball Gossip,” Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1894: 6.

13 “Play Ball!” Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1894: 6.

14 “Giants Begin Badly,” New-York Tribune, April 20, 1894: 5.

15 “Off for the Pennant,” Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1894: 6.

16 “The Big Battle is On,” New York Sun, April 20, 1894: 4. For an informative description of the history of teams choosing to bat in the top or bottom half of the first inning, see Gary Belleville, “The Death and Rebirth of the Home Team Batting First,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2023. https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-death-and-rebirth-of-the-home-team-batting-first/.

17 “Beaten in the First Game,” New York Times, April 20, 1894: 3. Slightly different attendance totals were reported: The Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1894, reported 15,235, the New York Sun and both the April 20 editions of the New York Sun and the New-York Tribune reported it at 15,106. Retrosheet.org sets it at 15,300.

18 The Baltimore Sun, New York Sun, and New York Times assess Burke with an error on this play; however, the New-York Tribune credits McGraw with a hit and does not assign an error to Burke.

19 The New York Sun and New-York Tribune gives Murphy an error on this play, but the Baltimore Sun and New York Times credit Keeler with a hit.

20 “The Big Battle is On.”

21 “New York News: Reasons for the Bad Beginning in Baltimore,” Sporting Life, April 28, 1894: 3.

22 The Baltimore Sun and New York Sun credit Brodie with a stolen base, but the New York Times and the New-York Tribune assign a passed ball to Farrell on the play.

23 “Giants Begin Badly.”

24 “Beaten in the First Game.”

25 “Off for the Pennant.”

26 “Baseball Gossip.”

27 Frederick Lieb, The Baltimore Orioles: The History of a Colorful Team in Baltimore and St. Louis (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1955), 48-49. Ward may have had other reasons for his bitterness because it was reported that he “almost had to go heavily into business to pay his bets.” In all, Ward was said to have lost nine hats on the series and a suit of clothes to heavyweight boxer and Baltimore saloon owner Jake Kilrain. (Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1894: 7.

28 McGraw, My Thirty Years in Baseball, 70.

29 McGraw, My Thirty Years in Baseball, 70-71. McGraw wrote these comments in his autobiography over 30 years later, so there might be a bit of romanticizing in hindsight. In that first series, the Orioles did not seem to employ tactics that were demonstratively more innovative than those used by the Giants; however, as the season progressed, comments in the press indicate that the Orioles increasingly perfected the tactics of scientific baseball and that it was a key factor in their success.

Additional Stats

Baltimore Orioles 8

New York Giants 3

Union Park

Baltimore, MD

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.