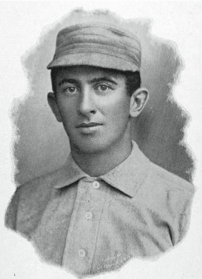

Willie Keeler

A diminutive lefty who was one of baseball’s biggest stars of the rollicking 1890s, Wee Willie Keeler continued to “hit ’em where they ain’t” through the first decade of the Deadball Era. The tiny (5-feet-4½-inches, 140 pounds) right fielder’s career covered 19 big-league campaigns, and in 13 of them – every year from 1894 to 1906 – he hit over .300 and ranked in his league’s top ten in hits. Eight straight times he collected more than 200 hits, and his .424 average in 1897 is the highest single-season mark by a left-handed hitter in baseball history. Keeler compiled a .341 career batting average and racked up 2,932 hits – 85 percent of them singles – in 2,123 games. An amiable Brooklyn native who was the son of Irish immigrants, Wee Willie played for all three New York teams (the Brooklyn Superbas, the Highlanders, and the Giants), and was a key member of the raucous Baltimore Orioles dynasty of the 1890s.

A diminutive lefty who was one of baseball’s biggest stars of the rollicking 1890s, Wee Willie Keeler continued to “hit ’em where they ain’t” through the first decade of the Deadball Era. The tiny (5-feet-4½-inches, 140 pounds) right fielder’s career covered 19 big-league campaigns, and in 13 of them – every year from 1894 to 1906 – he hit over .300 and ranked in his league’s top ten in hits. Eight straight times he collected more than 200 hits, and his .424 average in 1897 is the highest single-season mark by a left-handed hitter in baseball history. Keeler compiled a .341 career batting average and racked up 2,932 hits – 85 percent of them singles – in 2,123 games. An amiable Brooklyn native who was the son of Irish immigrants, Wee Willie played for all three New York teams (the Brooklyn Superbas, the Highlanders, and the Giants), and was a key member of the raucous Baltimore Orioles dynasty of the 1890s.

A two-time batting champion and a three-time league leader in hits, he had the speed to leg out infield singles, the bat control to drop down bunts, chops and rollers in front of infielders, and when they moved in, the ability to loft a base hit over their heads. He finished his career with 366 sacrifice hits, the fourth highest total in major-league history. “Keeler could bunt any time he chose,” Honus Wagner remembered. “If the third baseman came in for a tap, he invariably pushed the ball past the fielder. If he stayed back, he bunted. Also, he had a trick of hitting a high hopper to an infielder. The ball would bound so high that he was across the bag before he could be stopped.” Wee Willie wielded a bat that was just 30 inches long, the shortest ever used in the majors, and he choked up so far that Sam Crawford said, “He only used half his bat.” Keeler himself suggested, “Learn what pitch you can hit good, then wait for that pitch,” but he is best remembered for his description of his hitting style to Brooklyn Eagle writer Abe Yager. “I have already written a treatise and it reads like this: ‘Keep your eye clear and hit ‘em where they ain’t; that’s all.’ ”

William Henry O’Kelleher was born on March 3, 1872, in Brooklyn. His father, also christened William O’Kelleher, 12 years earlier had left the farm in County Cork, Ireland, where he had been born, and at the age of 26 settled in Brooklyn and married another recent Irish immigrant, Mary Kiley. He came to be known as Pat Keleher (or Pat Kalaher) and toiled as a trolley switchman on the DeKalb Avenue Line. The couple purchased a home in Brooklyn’s Bedford neighborhood and Mary gave birth to two sons, Tom and Joe, prior to the arrival of William, sometimes known as “W.H.,” but more often as “Willie.” A brother and a sister followed, but only Willie and his two older brothers survived to adulthood.

As a youngster Willie Keleher played early versions of baseball and boxed. He served as captain for his Public School 26 team and at the age of 14 began to play for the Rivals, a local amateur team. He quit school at 15 to play for a factory team, though he never worked in the factory. His father found him a job at a different factory, one that made cheese, and Willie worked there for a week. He earned $2, left early on Saturday, and earned $3 to play in a ballgame at Staten Island. He never returned to the factory or held a job outside of baseball. Later, he would state, “Say, I think I’m the luckiest guy in the world. I get paid for doing what I’d rather do than anything else – play ball.”

At 16 he played for the semipro Acmes for $1.50 a game, and over the next three years traveled on street cars and ferries to play for semipro teams in the Flatbush, Flushing, Arlington, and Ridgeway areas of Brooklyn, and for the Aces, Allertons, and Sylvans in New Jersey. He also sold programs at Eastern Park, home of “Ward’s Wonders,” Brooklyn’s 1890 entry in the Players League. That summer he joined the Crescents of Plainfield, New Jersey, and drew $60 a month as a pitcher and third baseman. By 1891, when he led the Central New Jersey League with a .376 average and guided the Crescents to the circuit’s championship, he was known as Willie Keeler.

Keeler started the 1892 season with Plainfield, and then broke into Organized Baseball in June when Herm Doscher signed him to a contract to play for Binghamton (New York) of the Eastern League for $90 a month. Later that summer, the New York Times reported that “Keeler’s debut as a ball player was very peculiar. Early in the spring the Binghamptons realized that they wanted a short stop, and the Secretary of the club was sent out to find one. In his rambles he visited one of the many parks on Long Island where semi-professionals play Sunday games. Keeler was connected with some obscure team, but his work struck the fancy of the Binghampton man and he decided to engage him right on the spot. He was taken to Binghampton and his work from the start won him many friends in all the cities visited by his team. Keeler was put at the top of the batting list for his club and he remained there all season. At first he played at short, but the man at third was not giving satisfaction, so he was transferred to the corner of the diamond.”

Keeler led the Eastern League in batting with a .373 average, but the little lefty made 48 errors in 93 games for the Bingos. National League scouts were willing to overlook his deficiencies in the field because of his hitting, and on September 27, New York Giants manager Pat Powers purchased his contract for $800. “Nearly every club in the League had an agent here, and Keeler had some flattering offers made him,” the New York Times reported the next day. “Manager Powers’s oily tongue and persuasive manners, however, had the desired effect and Keeler decided to cast his lot with the Giants to the disappointment of the other agents.” After he signed a contract for $1,600, the Times gushed, “In young Keeler the New Yorks have a prize, and he will surely make his mark in the League. … He is a clever fielder, a remarkably fast man on the bases, and as a batter he outranks any other player in the Eastern League.”

Keeler made his big-league debut at the age of 20 on September 30, 1892, at the Polo Grounds with an infield single and two stolen bases against Philadelphia’s Tim Keefe. He appeared in 14 late-season games as a third baseman – he was said to be only the second regular left-handed third basemen in major league history – and stroked 17 hits, including three doubles, in 53 at-bats, a .321 average. He was back with the Giants to start the 1893 season, but John Montgomery Ward had replaced Powers as manager, and limited Keeler’s early-season playing time to just seven games. The little lefty played two games at shortstop, two at second base, and three in the outfield, and smacked eight hits in 24 at-bats, including the first of his 145 career triples and the first of his 33 career home runs. He stroked the inside-the-park circuit clout on May 9 with one runner aboard against right-hander William “Brickyard” Kennedy, a future teammate in Brooklyn. The next day he fractured his leg sliding into second base, missed eight weeks of the season, and on his return, was shipped to the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, who by that time occupied Eastern Park, for $800. Keeler batted .313 for his hometown team, and hit another inside-the-park home run, but opposing batters bunted mercilessly against the little lefty, he committed 10 more errors in 12 appearances at the hot corner, and was banished back to Birmingham, where he made 11 more miscues in 15 games.

Keeler didn’t appear to fit into Brooklyn’s plans because of his small size, but he had caught the shrewd eye of Baltimore Orioles manager “Foxy Ned” Hanlon. On January 1, 1894, Hanlon acquired Keeler and star first baseman Dan Brouthers from Brooklyn in exchange for journeymen Bill Shindle and George Treadway in one of baseball’s most lopsided trades.

Hanlon installed Keeler as the regular right fielder in a lineup that included John McGraw, Hughie Jennings, Wilbert Robinson, and Joe Kelley, launching one of baseball’s great dynasties. Batting atop the Oriole order, McGraw and Keeler – with the help of legendary groundskeeper Tom Murphy – perfected the Baltimore Chop, driving the ball into the infield dirt and beating out the resulting high hop, and though they didn’t invent the hit-and-run, Muggsy and Wee Willie turned it into an art form. Keeler was also an excellent bunter, possessed great bat control, and was a master at fouling off pitches with his tiny bat, reported to weigh just 29 ounces. “Keeler had the best batting eye I have ever seen,” McGraw said. “He held his bat away up in the middle with only about a foot of it extending beyond his hands and he could slap the ball to either field. It was impossible to play for him. I have seen the outfield come in behind the infield or the infielders close up till you’d think you couldn’t have dropped the ball into an open spot if you had it in your hand – but Keeler would invariably punch a base hit in there somewhere.”

Keeler punched at least 210 hits each year between 1894 and 1898. During that five-year span he batted .388, averaging 223 hits, 74 runs batted in, 48 steals, and 278 total bases. A master at reaching base and a wizard on the basepaths, he averaged 150 runs per year and finished second in the National League in that category four straight times. He also became an asset in the outfield. After Hanlon moved the reluctant Keeler to right field and persuaded him to don a glove, he became a fleet and instinctive defender. “He knew his territory like a child its ABC’s,” Orioles center fielder Steve Brodie remembered, and McGraw called Keeler’s diving barehanded catch in Washington in a game in June 1898, for which he had to stick his throwing arm into a barbed-wire barrier, the greatest he ever witnessed.

However, McGraw often needled Keeler for his defensive lapses, and during the 1897 season, the two teammates brawled naked in the shower room of the Orioles clubhouse as teammate Jack Doyle, a Muggsy antagonist, stood guard to prevent interference. As Doyle had predicted, McGraw was the first to “squeal.”

While fighting with their opponents and feuding with one another, the innovative Orioles posted a 452-214-17 record between 1894 and 1898, finished atop the 12-team National League in Keeler’s first three seasons in Baltimore and second in his final two, and captured the Temple Cup twice by winning the postseason playoff series between the league’s top two regular-season teams. Keeler, who didn’t drink or swear, was generally regarded as the genteel, friendly, and polite member of the rough-and-tumble Orioles dynasty, though he wasn’t above using deception to gain an edge. The Orioles were a surly bunch who argued with umpires, intimidated opponents, and brawled among themselves. They were also competitive innovators who developed a brand of “inside baseball” that would define the next two decades of major-league play.

Keeler’s addition made an immediate impact. Hanlon’s Orioles jumped from an eighth-place finish in 1893 to the pennant in 1894, though they lost the Temple Cup to the runner-up Giants, four games to none. Keeler batted .371 with 219 hits (third best in the National League) in 129 games, and established career-high watermarks for runs batted in (94), doubles (27), triples (22), and home runs (5), including two of the three he hit over the fence during his career. He struck out just six times, and reached base 58 times when he either walked or was hit by a pitch. He also stole 32 bases and scored 165 runs, at the age of 22.

The Orioles won another title in 1895, though they again lost the Temple Cup, falling to runner-up Cleveland four games to one. Keeler, by then referred to by newspaper writers as Wee Willie, a turn of a phrase from a popular children’s rhyme, batted .377, collected 213 hits and reached base 254 times in 131 games, stole 47 bases, and scored 162 runs. “Too think that so small a man as Keeler should lead all the League’s sluggers!” Sporting Life gushed. “Truly it is the eye and not the size.”

Wee Willie wielded his tiny bat in a big way again in 1896, when he collected 210 hits and reached base 254 times in 126 games. His .386 average was the league’s fourth best, his hit total ranked second, and he stole a career-high 67 bases, seventh in the league, but just fourth among the aggressive Orioles, and scored 153 runs. Baltimore won its third straight pennant and earned its first Temple Cup when the Orioles dispatched runner-up Cleveland four games to none. After the series, “The Big Four,” Keeler, McGraw, Jennings, and Kelley, celebrated with a tour of Europe.

Wee Willie had hit safely in his final regular-season game in 1896, and he opened the 1897 campaign by collecting safeties in each of the first 44 games of the 1897 campaign to eclipse the previous National League record of 42 straight games established by Bad Bill Dahlen of the Chicago Colts in 1894. Keeler’s 45-game streak stood as the major-league mark until 1941, and is still the National League record.

Keeler continued to hit all summer, collected a league high 239 safeties in just 129 games, and finished with a .432 average. Although it was later adjusted to .424, it remains the best single-season mark by a left-hander and third best by any hitter since a rule change in 1888 decreed that bases on balls would no longer be counted as hits. He reached base safely 281 times in 606 plate appearances, an on-base percentage of .464. Though he never homered during the stellar season, he did smack 27 doubles and 19 triples, and finished second in the league in slugging with a .539 mark. He stole 64 bases and scored 145 runs (second in the league for the fourth straight season). The Orioles slipped to second place behind Boston despite Keeler’s superb season, but Wee Willie extended his torrid season into the Temple Cup series. He collected eight hits in 17 at-bats, a .471 average, and drove in four runs to help Baltimore baste the Beaneaters, four games to one.

In 1898 Keeler won his second straight batting crown with a .385 average and led the league in hits for the third time in four years, with 216. Boston and Baltimore finished one-two again. Keeler stroked just 10 extra base hits and stole but 28 bases. There was no postseason play because the Temple Cup had been discontinued, and forces were at work that would put an end to the Orioles dynasty that had played a key role in the development of inside baseball.

The end began when Hanlon and Orioles owner Henry Von der Horst acquired 56 percent of the stock in the National League’s Brooklyn franchise in exchange for a similar amount of stock in the Baltimore club. By doing so, they formed a partnership with Brooklyn owners Charlie Ebbets and F.A. Abell to gain control of both clubs, and moved to consolidate their strength. By early February the syndicate had transferred the contracts of Keeler, Kelley, Jennings, and other key Orioles to Brooklyn to join Hanlon, though McGraw and Wilbert Robinson chose to stay in Baltimore. Keeler was elated to return to his hometown, and to be near his ill mother. “I can say frankly that I would rather play in Brooklyn, my home, than anywhere else,” he told the Brooklyn Eagle.

Back home in Brooklyn, which a year earlier had become a borough of New York City, and living in his parents’ house on Pulaski Street, Keeler teamed with Kelley and Dahlen, another Brooklyn native, to lead Hanlon’s Superbas to the National League pennant in 1899 by eight games over Boston. Keeler batted .379, fourth best in the league, collected 216 hits, reached safely 262 times and stole 45 bases. He hit just one home run. It was the only grand slam of his career. On May 15 Keeler caught Philadelphia’s Ed Delahanty playing a very shallow left field with two outs in the eighth and the bases loaded, laced a liner past him, and raced around the bases to give Brooklyn an 8-5 win at Washington Park.

Hanlon’s Superbas, bolstered by Jennings’ return from injury and the addition of pitcher Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity, outdistanced Honus Wagner’s Pittsburgh Pirates by 4½ games in 1900 to repeat as National League champion. Keeler again finished fourth in batting with a .362 average, stole 41 bases, smacked four homers, and led the league with 140 runs and 204 hits, a number that brought his career total to 1,567 in 4,114 at-bats through the close of the 1900 season, a batting average of .381, the best in baseball in the 19th century. He also played in one game at second base, and handled his only chance cleanly.

In 1901 Keeler had his eighth straight 200-hit season, finishing second in the league with 202, though his average slipped to .339. He played in 136 games, including 10 at third base and three at second, collected 18 doubles, 12 triples, and a pair of home runs, and stole 23 bases. He sacrificed 22 times and scored 123 runs, second best in the league, and led the league’s outfielders in fielding percentage at .985 (he would repeat in 1902).

The Superbas slid to third place and Hanlon and Ebbets, who now ran the team, struggled to keep their dynasty intact. In its inaugural season, the American League had lured several National League stars with contracts that paid more than more than the $2,400 salary cap imposed by the senior circuit upon its players. With a competitive market for their services, Keeler, Kelley, and Dahlen all demanded raises to stay in Brooklyn. “Keeler, the team’s biggest star, naturally was the most sought after, receiving solicitations from six of the eight American League clubs,” baseball historian Lyle Spatz wrote in his biography of Dahlen. “Chicago was one, with an offer of a two-year contract at $4,300 per year. Another was Detroit, which was willing to pay him $5,000 to play with the Tigers. Hanlon did not expect Keeler to take any of those offers, but did worry about one that came from John McGraw in Baltimore. McGraw, Keeler’s ex-teammate with the National League’s Orioles and now the manager of the American League Orioles, had already lured two old Orioles, Kelley and Joe McGinnity, back to Baltimore. No doubt McGraw lobbied hard for Keeler too when ‘Wee Willie’ served as an usher at his second marriage in January, 1902.” The New York Times reported that “Keeler may be induced by an offer of a stock interest to return to that club, as he has time and again said that he would rather play with Baltimore than with any other club in the country.”

John Montgomery Ward, who as the manager of the Giants had once sold Keeler’s contract to Brooklyn, was one of 50 individuals who contributed a total of $1,000 to help Hanlon and Ebbets keep Keeler, the hometown hero, in Brooklyn. Wee Willie re-signed the sweetened contract in February and told the New York Times. “I expect to play ball for six or seven years longer, and while it is not absolutely necessary for me to continue on the diamond as I have been unusually lucky in my investments, still the questions was whether I should take a chance on a couple of years elsewhere or a longer period here, where I am known and where my future is the brightest. If I ever get out of baseball it is here that I shall be and it is here that I expect to make friends. Consequently, I decided to stick to Brooklyn.”

Dahlen also re-signed, but Kelley jumped to join McGraw’s American League Orioles, and Hanlon designated Keeler team captain. After serving as the Harvard hitting coach early in the spring – Cy Young coached the pitchers – Keeler filled in as acting manager of the Superbas until Hanlon arrived later. Once the season started, Keeler, 30, started to show signs of age. After a record-setting eight straight years of 200 hits, he rapped out 186, second in the league, batted .333, scored 86 runs, and stole 23 bases, but those were all nine-year lows. He was also ejected once, the only time in his career the easy-going Keeler was ordered out of a game. Hanlon’s Superbas finishe second, but a whopping 27½ games behind Pittsburgh, which had been less damaged by American League raids than other teams. Hanlon and Ebbets again hoped to hang on to Keeler, but Chicago’s Charlie Comiskey, Philadelphia’s Connie Mack, and the ownership in Detroit – now offering $10,000 – were among those who came courting. When Wee Willie’s contract with the Superbas expired at the end of the season, so did his union with Hanlon that had produced five pennants and two Temple Cup victories.

The day after the season ended Keeler boarded a train for a barnstorming trip in California. During a layover in Chicago, he made a trip to American League President Ban Johnson’s office and asked if rumors that the league would place a team in New York in 1903 were true. Assured that they were, Keeler signed an American League contract for $11,000, a figure suggested by Johnson, and became baseball’s first $10,000-a-year player. “We can count on our fingers the number of years we will be able to play,” Keeler had told the New York Clipper earlier in his career. “That makes it plain that we must make all the money we can during the short period we may be said to be star players.”

Keeler asked that Johnson wait to announce the signing and continued on to California, where he played in exhibition contests against other big leaguers over the Thanksgiving weekend. On that Sunday night, a horse-drawn surrey that carried Keeler, Jack Chesbro, Jake Beckley, and Joe Cantillon overturned. The burly Beckley landed on top of Wee Willie, who injured his leg and throwing shoulder and likely dislocated his collarbone. He felt the effects of the accident through the remainder of his career.

Keeler returned home to recover, and in the early part of 1903, Brooklyn Eagle writer Abe Yager visited him to confirm the news that he had signed with the junior circuit. “Sure,” Willie replied. “The people here can’t give me the money the American League has promised me. I signed with them when I was in Chicago a couple of months ago. I’ve only a few years longer to play ball and the money they offered me was enough to induce me to leave Brooklyn. I signed only a one-year contract with Hanlon and I believed myself free to sign where ever I liked.”

Keeler’s contract was assigned to the “Greater New York Team,” which had originated in Baltimore. McGraw had managed the Orioles in the American League’s inaugural season, but incessantly feuded with the new league’s umpires and president. He released a number of the team’s top players and jumped back to the National League during the 1902 season to become manager and part-owner of the Giants, leaving the depleted Orioles to finish dead last in the American League. That was more than enough motivation for Ban Johnson, who had envisioned an American League presence in the nation’s largest city, to invade Manhattan and cut into the Giants’ box-office revenue.

Johnson moved the league offices to New York, handpicked owners Frank Farrell and William Devery, found a suitable location and built Hilltop Park, orchestrated the hiring of Clark Griffith as manager, and transferred Keeler’s contract to the New York Americans as part of his effort to restock the franchise. Commuting from his home in Brooklyn to Hilltop Park, in the northernmost part of Manhattan, Wee Willie played 128 games in the outfield and four at third base, batted .313, collected 160 hits, stole 24 bases, sacrificed 27 times, and scored 95 runs. Keeler’s batting average was fifth best in the league, but the lowest of his career to that point. Before the season, the American League had changed its rules to count foul balls as strikes on strike one or strike two. The rule affected Wee Willie, who was adept at fouling off pitches he didn’t want to hit. After the rule was adopted, American League batting averages declined from .275 to .255 to .244 in a three-year span.

Keeler and pitcher Jack Chesbro coached at Harvard in the spring of 1904, and then returned to lead the Highlanders to within a wild pitch of the pennant. Chesbro won 41 games. Keeler stroked 186 hits and finished with a .343 average and a .390 on-base percentage, second best in the league behind Cleveland’s Nap Lajoie in all three categories. He finished fifth in the league in sacrifice hits (27) and ninth in slugging percentage (.409).

In 1905 Keeler, at .302, was again the runner-up for the batting title as American League batting averages continued to plummet. He collected 169 hits and reached base at a .357 clip. He led the league in sacrifice hits with a career-best 42, and he made his final infield appearances when he played three games at third and 13 at second base.

Keeler hit .304 in 1906, his final season as a full-time player. He collected 180 hits, scored 96 runs, and sacrificed 26 times. The Highlanders finished second again under Griffith, four games behind Chicago’s Hitless Wonders.

In 1907 New York fell to fifth, and at the age of 35, Wee Willie for the first time in his major-league career failed to hit. 300. He batted just .234 in 109 games as injuries and declining speed took a toll on his ability to beat out infield hits. More and more reliant on his bunting ability, Wee Willie laid down 26 sacrifice hits. Although his bat still measured just 30 inches long, by this time Keeler used a 36-ounce Louisville Slugger.

He revived his career in 1908 by batting .263 in 91 games, but New York slipped into the cellar and Griffith resigned early in the season. Team owner Farrell wanted Keeler to take the helm, but Wee Willie was unwilling, and hid out until Farrell tabbed shortstop Norman “Kid” Elberfeld to finish out the season. Under the Tabasco Kid, the Yankees won just 27 of 98 games. Disgusted by Elberfeld’s “surly managerial style,” Keeler left the team with six weeks remaining in the season, and announced that he would retire, but after the season, Farrell sold Elberfeld to Washington and persuaded Keeler to return. “Yes I am going to quit baseball,” Keeler told Sporting Life with a wink, “but it won’t be until the wrinkles choke me to death.”

Despite missing time with a severe charley horse and a severed tendon in his foot, Keeler, at 37 the sixth oldest active player in the majors in 1909, served as team captain, and batted .264 in 99 games. He ranked among the league leaders in just one category, sacrifice hits, where he was fifth with 33. The Highlanders climbed to fifth place under new manager George Stallings.

After the season Farrell offered to trade Keeler, but out of respect to the veteran player released him to make his own deal. On May 6, 1910, Wee Willie moved to the other side of Manhattan to reunite with McGraw, who routinely reunited with his old teammates and former players for sentimental reasons. Keeler served as batting coach and pinch-hitter, and on August 25 stepped in to help umpire a game in Chicago. He appeared in just 19 games, collected the final three hits of his major-league career, and stole a base for the 495th time. He played in his final major-league game at the age of 38 when he unsuccessfully pinch-hit in the ninth inning of the morning game of a September 5 doubleheader at Washington Park, his first appearance in a game in Brooklyn since he left Hanlon’s Superbas. As only one player, Cap Anson, had amassed 3,000 hits up to that time, the fact that Keeler was just 68 hits shy of 3,000 went virtually unnoticed. Wee Willie played one more year of Organized Baseball. He joined old teammate Joe Kelley, who was manager of the Eastern League’s Toronto Maple Leafs, and collected 43 hits in 39 games in 1911.

Keeler could always count on old teammates for a job, and he returned to Brooklyn in 1912 to rejoin Dahlen, who was in the third of four seasons as Dodgers manager. The Chicago Defender reported that “Willie Keeler, who is the Brooklyns’ coach and scout, is receiving $600 a month for his valuable services. Keeler and Dahlen, old pals, keep their heads close together. They are trying to make the Brooklyns play some inside ball.”

Ebbets replaced Dahlen with another old teammate, Wilbert Robinson, after the 1913 season. Keeler served with the Brooklyn Federal League team, the Tip-Tops, as a coach in 1914 and the early part of 1915, and was a scout for George Stallings’ Boston Braves later in 1915.

Keeler was known as the Brooklyn Millionaire when he retired from baseball, though his actual net worth was likely less than $200,000. He had invested his baseball earnings in mining stocks, a number of successful business ventures, including some with teammates, and real estate, purchasing commercial lots in New York City, and when he retired he bought a gas station in Brooklyn. But Willie contacted tuberculosis, his lifelong allergies worsened, the gas station failed, and when the real-estate market lost its speculative value after World War I, Keeler found himself broke and he and his brothers were forced to sell their childhood home.

By the early 1920s Keeler suffered from heart disease, and endured chest pains and rapid breathing. He attended a major-league game for the final time when he visited the Polo Grounds for Game Six of the 1921 World Series between the Yankees and Giants. Two months later Ebbets presented him with a check for $5,500 after the owners in the two leagues each contributed to a fund to help him pay off his debts. His health continued to fail and Keeler was too ill to attend a reunion of the old Orioles in Baltimore, though many of his old teammates later visited him. He knew he was losing the battle for his life during the holiday season of 1922, but vowed to see 1923. On New Year’s Eve, several well-meaning friends stopped by to congratulate him and cheer him up. When Willie became exhausted, they left him alone, rang in the New Year, and returned to find that he had died. He was 50 years old. The cause of death was chronic endocarditis, an inflammation of the lining of the heart that Keeler had probably suffered from for at least five years. He also appeared to suffer from dropsy, better known today as edema, swelling of tissues because of an excessive accumulation of watery fluid, another symptom of heart trouble.

Though Willie was a lifelong bachelor, he lived the final years of his life as a boarder in a house on Gates Street that belonged to Clara Moss, and left his entire estate of $3,500 to her. “The newspapers said he was living with his sister, but Willie Keeler had no sister,” Burt Solomon wrote in Where They Ain’t, a history of the Orioles. “All that he had, he left to Clara. In the end, Willie Keeler found love.”

Although he died less than 13 years after his final major-league game, Keeler was remembered as an “Old Time Ballplayer” in his New York Times obituary. Keeler died without money but with a wealth of friends, and his funeral was attended by many of his old teammates as well as some of baseball’s greatest players and managers. Keeler was laid to rest in Queens’ Cavalry Cemetery in the grave of his beloved mother, at his request. To place a memorial to the former baseball star on the grave, her headstone was moved to become a footstone.

In 1936 Keeler’s name was on the initial ballot for the Baseball Hall of Fame. He received 18 percent of the vote from the Baseball Writers Association of America, and he was named on 42 percent of the Veterans Committee ballots. The following year, he received 57 percent of the BBWAA vote, then 68 percent in 1938, and was elected in 1939 when he captured 75.5 percent of the vote. In June 1939 Keeler was one of 26 baseball immortals inducted at the formal opening of the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

In 1941 the nation followed Joe DiMaggio’s pursuit of Keeler’s record 45-game hitting streak as the Yankee Clipper drew near the mark, matched it, and then extended the record to 56 games. In 1978 national attention focused on Philadelphia’s Pete Rose, who matched Keeler’s National League single-season hitting streak of 44 games but ended one shy of Wee Willie’s NL mark of 45 over the 1896 and 1897 seasons.

In 2008, more than a century after Keeler used his tiny bat to rap out 200 hits in eight straight seasons, Seattle’s Ichiro Suzuki matched his mark. He broke Keeler’s record in 2009 and extended the major-league record to 10 by the end of the 2010 season. Wee Willie continues to hold the National League record.

Keeler was named the center fielder (and McGraw the manager) for the All-Irish team, one of five ethnic squads selected by sportswriter Harry Stein in 1976 for his “All Time All-Star Argument Starter,” for Esquire magazine. Because of space limitations the All-Irish team was edited out, though it later appeared in print.

Keeler was also immortalized in Ogden Nash’s classic 1949 poem, “Line-Up For Yesterday,” matching a baseball legend to each letter of the alphabet:

K is for Keeler,

As fresh as green paint,

The fastest and mostest

To hit where they ain’t.

Keeler ranked 75th on The Sporting News list of the 100 greatest baseball players, and in 1999 he was named as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, though he had spent his best years in the 19th century.

Last revised: April 17, 2023 (zp)

Sources

Adomites, Paul, et al. Hall of Fame Players: Cooperstown. Publications International, 2007.

Alexander, Charles, John McGraw, New York: Viking, 1998.

Alexander, Charles. Our Game: An American Baseball History. New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1991.

Anderson, David. More Than Merkle: A History of the Best and Most Exciting Baseball Season in Human History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Appel, Marty, and Burt Goldblatt. Baseball’s Best: The Hall of Fame Gallery. New York: McGraw Hill, 1980.

Armour, Mark, and Daniel Levitt, Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way, Dulles, Virginia: Brassey’s, 2003.

Astor, Gerald. The Baseball Hall of Fame 50th Anniversary Book. New York: Prentice Hall, 1988.

Fleitz, David. The Irish in Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009.

Honig, Donald. The American League: An Illustrated History, New York: Crown, 1983.

Honig, Donald. The National League: An Illustrated History, New York: Crown, 1983.

Hoppel, Joe. From the Archives of the Sporting News: Baseball: 100 Years of the Modern Era: 1901-2000. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 2001.

James, Bill, John Dewan, Neil Munro, and Don Zminda, All Time Baseball Sourcebook, Chicago: STATS Inc., 1998.

James, Bill. The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Villard, 1986.

——:. The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works. New York: Macmillan, 1994.

Kavanagh, Jack, “William Henry Keeler (Wee Willie).” In Baseball’s First Stars. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996.

Kavanagh, Jack, and Norman Macht. Uncle Robbie. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1999.

Lieb, Fred. Baseball As I Have Known It. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

McConnell, Bob, and David Vincent. The Home Run Encyclopedia, New York: Macmillan, 1996.

Morris, Peter. Level Playing Fields: How the Groundskeeping Murphy Brothers Shaped Baseball. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball. New York: Donald I. Fine Books, 1997.

Okkonen, Marc. Baseball Memories: 1900-1909. New York: Sterling, 1992.

Reidenbaugh, Lowell. Baseball’s Hall of Fame: Cooperstown: Where the Legends Live Forever. St. Louis: Sporting News, 1999.

Segar, Charles, ed. National League 75th Anniversary. New York: Jay Publishing, 1951.

Solomon, Burt. Where They Ain’t: The Fabled Life and Untimely Death of the Original Baltimore Orioles, the Team That Gave Birth to Modern Baseball. New York: Free Press, 1999.

Smiles, Jack. The Life and Times of Hughie Jennings, Baseball Hall of Famer. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFar;land, 2005.

Smith, Ken. Baseball’s Hall of Fame. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1952.

Spatz, Lyle, Bad Bill Dahlen: The Rollicking Life and Times of an Early Baseball Star, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004.

Spink, Alfred. The National Game. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University. 2000.

Stout, Glenn, and Richard Johnson. The Dodgers: 120 Years of Dodgers Baseball. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004.

Stout, Glenn, and Richard Johnson. Yankees Century, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2002.

Thorn, John. Treasures of the Baseball Hall of Fame. New York: Villard Books, 1998.

Wilbert, Warren. The Arrival of the American League. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007.

Brooklyn Eagle

Chicago Defender

New York Clipper

New York Times

New York Tribune

Harvard Crimson

Sporting Life

The Sporting News

Baseball Hall of Fame

Baseball Library

Baseball-Reference

Louisville Slugger

Retrosheet

Society for American Baseball Research

Full Name

William Henry Keeler

Born

March 3, 1872 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

January 1, 1923 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.