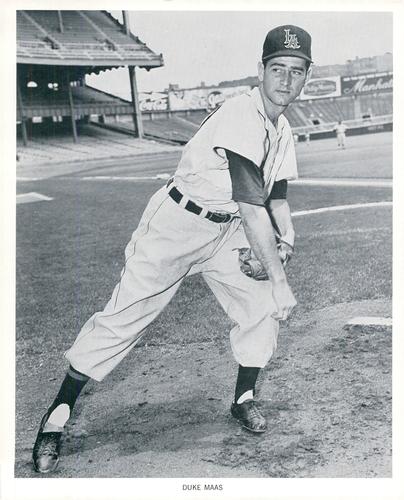

Duke Maas

Duke Maas pitched in the American League during seven seasons from 1955 to 1961, most notably with the New York Yankees. He appeared in relief in the 1958 and 1960 World Series.

Duke Maas pitched in the American League during seven seasons from 1955 to 1961, most notably with the New York Yankees. He appeared in relief in the 1958 and 1960 World Series.

Maas won the game that clinched the 1958 pennant for New York. In 1959 he started 21 games, fashioning a 14-8 won-loss record for a Yankees team that finished a disappointing four games over .500. He played his entire career, cut short by arthritis in his arm, having shaved two years off his age.

Maas told The Sporting News in 1957 that he didn’t like his given name, Duane, so he adopted the nickname Duke as a child.1 The 1957 Baseball Register said his father gave him the nickname. His father was a second-generation dairy farmer in Utica, Michigan, where Duane Frederick Maas was born on January 31, 1929, the younger of two sons of Frederick and Mabel (Weier) Maas.2 Duane’s brother, Lawrence, was born in 1926. Their paternal grandfather had emigrated from Germany.3 His mother also was of German descent.4

“They say milking cows strengthens your wrists, and I did a lot of that as a kid,” Duke told Watson Spoelstra of the Detroit News while he pitched for the Tigers. With chores to do on the family’s 60-acre farm, Maas didn’t play organized baseball until he made the Utica High School varsity as a senior. Utica, in Macomb County, is about 25 miles from Detroit.5

“Pitchers on the baseball team got to leave an hour early,” Maas told an Associated Press reporter in 1955 about his motivation. “So I tried out for the team and made it. That was in 1948, and I’ve been pitching ever since.”6

After graduation, Mass pitched for a Utica team in the semipro Macomb County Federation League, winning 12 and losing twice, His high-school coach, Barney Swinehart, wrote to the Detroit Tigers to see if they would take a look at Maas, a slim 5-foot-10 right-hander.7 In the fall of 1948, he and Swinehart went to Briggs Stadium for a tryout, but the Tigers’ longtime chief scout, A.J. “Wish” Egan, wasn’t available to see Maas when he arrived.

“Mr. Egan had been ill and wasn’t there the first day,” Maas told The Sporting News in March 1955.8 “So I went back the following day. He signed me that afternoon.” Tigers general manager John McHale gave Maas $500 and a $150-a-month contract.9

The 20-year-old Maas was assigned to Roanoke Rapids in the Class-D Coastal Plain League at the beginning of the 1949 season. He went 3-5 with a 4.01 earned-run average before moving on to Dunn-Erwin in the Class-D Tobacco State League. Although he was 3-2, his ERA was 5.25. He yielded nearly a hit per inning. With both teams, his control was shaky – 10 walks every nine innings overall.

The results, at least in the won-lost column, were better in 1950 for Jamestown, New York, in the Class-D Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York (PONY) League. Maas was 12-7, starting 19 of 30 games. He cut down on his walks and hits per inning, but his ERA was still 4.47.

With the Korean War raging, Maas was drafted into the Army. He was stationed first at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, before being sent to Germany to serve with the occupation force there for 14 months. He had no opportunity to pitch. He even had to play the outfield on an Army team at Fort Campbell. “I couldn’t make the club as a pitcher,” he said in 1955.10

Released from the military, Maas was sent in 1953 to Durham, North Carolina, the Tigers’ affiliate in the Class-B Carolina League. His won-lost record for a losing team was 6-16, but his overall performance improved significantly. His ERA dropped to 3.03 and he cut his walks per nine innings to less than four. The next season was a breakout for Maas: 18-7 combined at Double A and Triple A with a 2.37 ERA. He was the Eastern League’s top pitcher at Wilkes-Barre with three shutouts and a 1.10 ERA when he was promoted to Buffalo in the International League.

Maas’s 1954 season earned him a trip to spring training with Detroit in ’55. His impressive performance there won him a spot in the Tigers’ rotation to start the season. Veteran Tigers manager Bucky Harris called Maas “the surprise package” among the young pitching prospects.11 At first, Maas seemed as if he would be.

With the Tigers being blown out by the White Sox, Maas made his major-league debut on April 21, 1955, at Briggs Stadium. His team was down, 9-1, when he took the mound in the eighth inning to face Chico Carrasquel, who grounded out to short. Nellie Fox then grounded to second and Minnie Minoso grounded to third. The ninth wasn’t quite as smooth: Maas hit a batter and walked another, but escaped without a run scoring.

His first big-league start came at home on April 30 against Washington. It didn’t go well. Maas lasted just 2⅓ innings. He gave up just two hits, but walked five. Mercifully, Maas yielded only two runs. The Tigers won, 11-7.

Five days later, Maas started and won his first major-league game as the Tigers scored the winning run with two outs in bottom of the ninth on Al Kaline’s triple. Maas went the distance, allowing six hits and walking two.

“Everybody tells me the first victory is the toughest,” Maas told reporters. “I don’t see how they possibly could come any tougher.”12

After being knocked out early at Washington in his next start, Maas pitched another complete game at home to beat the Red Sox, 9-3. The Tigers were up 9-0 in the eighth when Maas yielded a meaningless three-run homer. He followed that with a complete-game, 3-2 victory over Cleveland on May 21. At that point, Maas was 3-1 with three complete games and a 3.27 ERA.

Although he shut out the Orioles twice – on June 5 and June 18 – he was knocked out in four innings or less in four of his next five starts. His ERA was 4.81 when he was optioned to Buffalo on July 18. A rookie named Jim Bunning replaced him in the rotation.

That fall, Maas married the former Nancy Gail Seeman, a 19-year-old local beauty pageant queen in Michigan, in a ceremony noted in The Sporting News. His “bride carried a satin catcher’s mitt and her “bridesmaid’s bouquets were arranged in shapes of baseball bats and balls.”13 The couple’s first child, Kevin, was born on Father’s Day in 1957. Another son and daughter – twins Randy and Robin – were born on September 8, 1960.14

After his demotion to the minors, Maas admitted to experiencing arm trouble, but in the spring of 1956, he told The Sporting News, “My arm felt good again at the end of last season.”15 And he again was making an impression on his manager.

“He is a fighter … who is always in top condition to pitch,” Harris said.16 The 1956 season was one to forget for Maas, however. His record was 0-7 with a 6.54 ERA when he was shipped in mid-July to Charleston in the American Association, the Tigers’ top farm club. There, he straightened himself out, winning six of nine decisions, including two shutouts, with a 2.39 ERA. He sharpened his control, walking just nine in 64 innings.

Maas began working more on a slider in the offseason, and it helped him make the Opening Day roster in 1957. That pitch “moves six to 12 inches just before it reaches the plate,” catcher Frank House said praise of Maas early in the season.17

When Frank Lary was hit by a line drive on April 26, 1957, Maas relieved him and pitched six scoreless innings. Put back in the rotation, he won his first five starts, completing four of them. After beating Washington on May 19, he was 6-1 with a 1.74 ERA.18

“I’ve finally mastered control of my pitches,” he told an Associated Press reporter. “It’s just a matter of using my head instead of my arm. I’ve always felt I could be a consistent winner in the big leagues. … It’s about time I made something out of myself.”19

On June 14, 1957, Maas hit his lone major-league homer in beating the Red Sox. He was never much at the plate with just 6 hits in 80 plate appearances that season; he had a .117 lifetime batting average.

His victory over Boston was his seventh, but wins were hard to come by after that. Maas didn’t win again until August 1. He lost seven of his last nine decisions to finish 10-14 with a 3.28 ERA in 26 starts and 19 relief appearances over 219⅓ innings. He saved six games. The game starts and innings pitched in ’57 would be Maas’s career highs. Despite his heavy workload, Maas went to the Caribbean during the offseason to pitch in Puerto Rican Winter League.20

On November 20, 1957, Maas was involved in a 13-player transaction, which remains the third largest in history, between Detroit and Kansas City. Billy Martin, sent to Detroit, was the key player for the Tigers in deal. The Athletics also sent an aging Gus Zernial and five others to Detroit. Maas and Bill Tuttle were the keys among the seven players acquired by the Athletics.

The next season, Maas found himself on the New York-Kansas City shuttle. The Athletics, a team that seemed as if it were still a Yankees farm club, shipped Maas and 41-year-old Virgil Trucks to New York on June 15 in exchange for Bob Grim and Harry Simpson. “The Yankees dropped by their favorite store in Kansas City and picked up an item that may turn out to be the year’s biggest bargain,” columnist Red Smith wrote of the Maas deal.21 Indeed, Maas helped the Yankees secure the 1958 flag, going 7-3 in 13 starts and 9 relief appearances. He started and won the pennant-clincher, on September 14.

Before the World Series began, Maas was presumed to be in line to start the third game against the Milwaukee Braves,22 but when Bob Turley was knocked out in the first inning of Game Two, Maas was brought in. Rather than douse the fire, he added fuel. Maas got a fly-ball out before a walk and a single allowed both runners Turley had left on base to score. Still, all Duke needed was to retire the opposing pitcher. Lew Burdette would have none of it. His three-run homer turned the game into an early rout and sent Maas to the showers with an ERA of 81.00.

Down three games to one, the Yankees came back to beat Milwaukee, but New York’s run of 14 pennants in 16 seasons hit a bump in 1959. Although New York fell to third place, Maas was second on the team in victories with 14. He beat the Indians five times and the Red Sox four. Nine of his 21 starts came as regular member of the rotation from May 27 to July 11, but otherwise he was the classic spot starter/long man, pitching out of the bullpen 17 times. In all four of his saves, he pitched two innings or more.

His 1959 performance had earned Maas a solid chance to be a consistent starter, but he experienced arm trouble during spring training and into April 1960.23 He lasted five innings in his only start of the season, on June 1. Between June 4 and July 21, he never pitched more than two innings in a game. He appeared just four times in June, an indication his arm might have been bothering him.

Nevertheless, Maas received a vote of confidence – in public, at least – from manager Casey Stengel. “Nobody likes the Duke but me,” Stengel said about stories that Maas was on the trading block. “He’s coming along.”24 Yet New York newspapers had reported earlier that the Yankees tried and failed to pass Maas through waivers so he could be sent to Triple-A Richmond.25

Maas pitched 3⅓ innings to earn a save on August 6. He had three more before the season ended, the last a four-inning save on September 21. The 70⅓ innings he threw in 35 games were his fewest since 1956, when he spent half the season in the minors. Still, he finished 1960 with a 5-1 record.

In Game One of the 1960 World Series, Maas pitched two innings, yielding an RBI double to Bill Virdon in the sixth in the 6-4 Yankees loss to the Pirates. This turned out to be the last moment in the spotlight for him. The arthritic condition of his pitching arm grew worse before the start of the 1961 season. Neither the Yankees nor the expansion Los Angeles Angels must have been aware of this, however.

Maas was among the seven players on the August 31, 1960, Yankees’ roster exposed to the expansion draft in December to stock the Angels and the new Washington team. (The Yankees and the other seven teams had to make an additional eight players available from the 40-man rosters.) The Angels made Maas the third pick – all three from New York – in the draft, but then traded him back to the Yankees on April 4, 1961, for infielder Fritz Brickell.

“Maas was one of two or three I hated to make available to the other clubs,” Ralph Houk, the new Yankees’ manager, said of the deal to reacquire the pitcher.26 “If he doesn’t make it, we will have lost nothing but an infielder on whom we had not counted,” said general manager Roy Hamey.27

That spring, Maas moved his family to California, where his wife and three children remained, even after he was traded back to New York, for about a year before returning to their home in Utica.28

Although the Yankees apparently never raised the issue, it’s hard to believe the Angels did not recognize that Maas had a sore arm during spring training. He didn’t pitch in a game for New York until April 23. Maas retired just one of the three batters he faced – on a sacrifice bunt. He was charged with two runs. After yielding a run-scoring triple to Brooks Robinson, he walked off a big-league mound for what turned out to be the final time.

Maas remained on the active roster until May 20, when he was optioned to Richmond in the International League. He reported there after several more days of treatment on his sore arm.29

Soon, it was obvious that Maas no longer could pitch effectively. He gave up 36 hits – six of them homers – in 27 innings over nine games at Richmond. His ERA was 7.67. His arm trouble did not improve. At 32, he called it quits. That fall, his Yankee teammates awarded him a $750 share of their 1961 World Series money.

In late October of 1961, the Yankees released Maas to Amarillo of the Double-A Texas League, although he never played there.30 Returning to Utica, his Michigan hometown, he was hired by the traffic department at the Ford Motor Co. plant there,31 where he worked until shortly before his death.

According to his son Randy, Duke Maas attended the Yankees’ Old Timers Game in New York in August 1967. Maas and his wife divorced in 1968.32

As his rheumatoid arthritic condition deteriorated, he was admitted to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Clinton Township, Michigan, in late November 1976, where he remained for two weeks until he died of congestive heart failure on December 7.33 Maas was 47. He is buried in Utica Cemetery.

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

I gratefully acknowledge the help of Randy Maas, Duke’s younger son, with this essay.

The statistical details on the player’s career and games are from baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Watson Spoelstra, “Hudlin Coaching Straightens Out Tigers’ Curving,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1957: 10.

2 1940 U.S. Census, accessed through familysearch.org. Throughout his pro career, team rosters listed Maas as having been born on January 31, 1931, as did Baseball Register. His 1976 obituary by the Associated Press correctly listed his age as 47. United Press International had him as 45. Today, all sources note his correct birthday, but I found no mention of when the discrepancy first was noted.

3 Ibid.

4 Telephone conversation with Randy Maas, Duke’s younger son, July 23, 2018.

5 Watson Spoelstra, “Hats Off,” Sporting News, May 29, 1957: 23.

6 Syd Kronish, Associated Press, “Chance to Beat School Bell Started Maas on Hill Career,” Mason City (Iowa) Globe Gazette, June 4, 1955: 9.

7 Spoelstra, “Hats Off.”

8 “Rookie Lives Near Park, But Has Seen Few Tiger Games,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1955: 17.

9 Spolestra, “Hats Off.”

10 Spoelstra, “Pair of Rookie Righties Brace Bengals on Mound,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1955: 14.

11 Spoelstra, “Bucky Plans to Join Casey and Richards as Pitching Juggler,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1955: 17.

12 United Press, “Duke Maas Wins First Tiger Game; Kaline Stars,” Holland (Michigan) Evening Sentinel, May 6, 1955: 11.

13 “Maas’ Bride Carries Satin Catcher’s Mitt at Wedding,” The Sporting News, November 23, 1955: 15.

14 “Stafford After Third,” World Telegram and Sun (New York City), September 9, 1960: page unknown, from clip file for Maas at Hall of Fame and Museum.

15 Spoelstra, “Maas Could Fill Tigers Need of ‘Another Hurler’,” February 15, 1956: 22.

16 Ibid.

17 Spoelstra, “Hats Off.”

18 Ibid.

19 Dave Diles, Associated Press, “Duke Maas Is Using Head, Winning,” Gettysburg Times, June 24, 1957: 5.

20 Telephone conversation with Randy Maas, July 23, 2018.

21 Red Smith, “Dealing From Fright,” New York Herald Tribune, June 17, 1958: B1.

22 Harold Rosenthal, “Ford Seen Yankees’ Series Key Again,” New York Herald Tribune, September 25, 1958: B1.

23 Tommy Holmes, “Yanks Deal Brickell to Angels to Regain Maas,” New York Herald Tribune, April 4, 1961: 29.

24 Dan Daniel, “Ol’ Prof Scribbles Question Marks on Yanks’ Curvers,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1960: 8.

25 Daniel, “Stengel Tells Why James Had to Go,” (New York) World Telegram and Sun, July 28, 1960: page unknown, from the Maas clip file at the Hall of Fame.

26 Holmes, “Yanks Deal.”

27 Daniel, “Yankees Need a Hitter,” World Telegram and Sun, April 4, 1961; page unknown, from Maas clip file at the Hall of Fame.

28 Telephone conversation with Randy Mass, July 23, 2018.

29 John Drebinger, “Tie Broken in 8th,” New York Times, May 21, 1961: S1.

30 Daniel, “Gibbs Tops List of 9 Newcomers on Yank Roster,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1961: 7.

31 William Hickey, “Where Are They Now?” Baseball Digest, July 1966: 82.

32 Telephone conversation with Randy Maas, July 23, 1968.

33 Associated Press, “Ex-Tiger Maas Dies, Escanaba (Michigan) Daily Press, December 8, 1976: 20, and telephone conversation with Randy Maas, July 23, 2018.

Full Name

Duane Frederick Maas

Born

January 31, 1929 at Utica, MI (USA)

Died

December 7, 1976 at Mount Clemens, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.