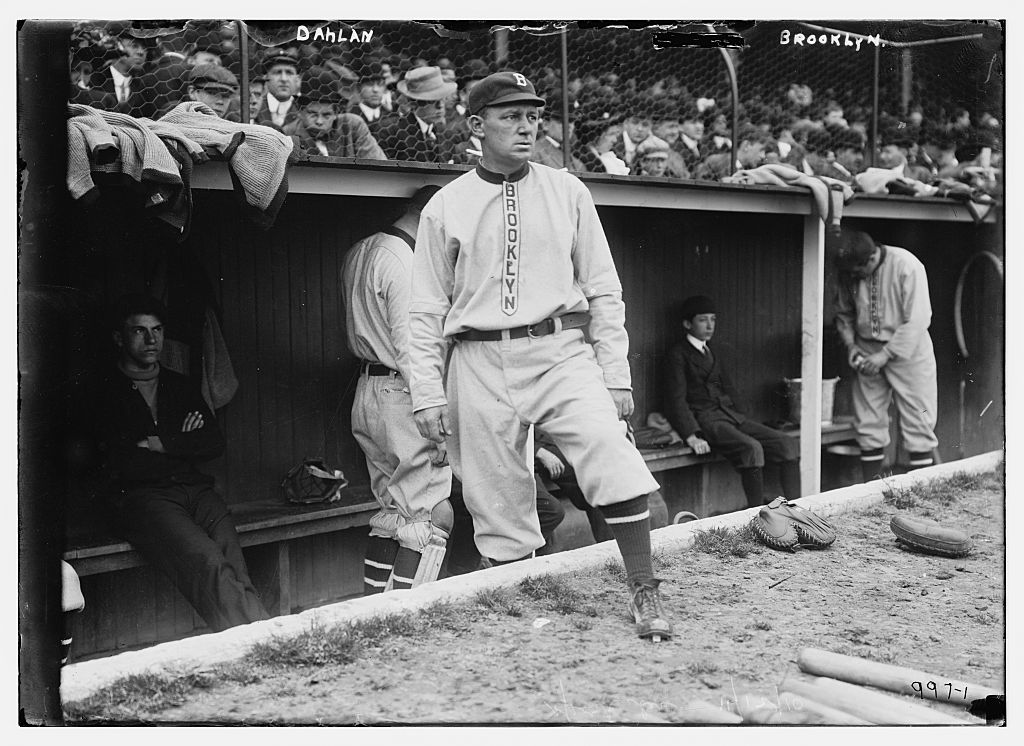

Bill Dahlen

Ferocious shortstop Bill Dahlen was ejected 65 times by umpires as a player and manager. This and other behavior earned him the nickname “Bad Bill.” Yet his rowdy character tended to overshadow his contributions—a reliable hitter; excellent, aggressive baserunner; and one of the finest fielders of his era (the 1890s and early 1900s). During his playing days, Dahlen did not receive full appreciation for his output; the passage of time has further obscured him. “Overlooked” and “underrated” are labels that a latter-day group of proponents has attached to him.

Ferocious shortstop Bill Dahlen was ejected 65 times by umpires as a player and manager. This and other behavior earned him the nickname “Bad Bill.” Yet his rowdy character tended to overshadow his contributions—a reliable hitter; excellent, aggressive baserunner; and one of the finest fielders of his era (the 1890s and early 1900s). During his playing days, Dahlen did not receive full appreciation for his output; the passage of time has further obscured him. “Overlooked” and “underrated” are labels that a latter-day group of proponents has attached to him.

Late in his career, as a manager, Dahlen’s leadership helped the Brooklyn Dodgers, but not because of his outbursts. His baseball acumen ignited Brooklyn’s escape from mediocrity in the 20th century’s second decade. However, Dahlen did not last long enough to taste the success built from his blueprint. He left Brooklyn after the 1913 season with a four-year managerial record below .500, a legacy of argument, and a pink slip from team owner Charles Ebbets. Wilbert Robinson, Dahlen’s successor, acknowledged his predecessor’s cultivation of a contender. Indeed, Robinson led Brooklyn to the 1916 National League pennant.

William Frederick Dahlen was born in Nelliston, a town in central New York, on January 5, 1870. His father, Daniel, was a German immigrant; his mother, Rosina (née Shellhorn), was the daughter of a German immigrant. William was born in his family’s home on a street that later was renamed Dahlen Street. His father was a legendary mason in Nelliston. Daniel had two marriages; the first Mrs. Dahlen passed away, leaving him with a daughter. Daniel’s second wife, Rosina, had five boys. Two died, leaving Daniel Jr., Harry, and William as the next generation of Dahlen males.1

Bill Dahlen attended elementary school in Nelliston and graduated from Fort Plain High School, near Nelliston. Even as a youth, he had a reputation as being a prankster—“the neighborhood live wire and pest.”2 Baseball was Dahlen’s ticket to education. He played for the Clinton Liberal Institute, also in Fort Plain, in exchange for tuition. Primarily a pitcher, Dahlen also filled in at second base. CLI boasted a U.S. president among its alumni—Grover Cleveland.3

Dahlen’s next stop was semipro baseball in 1889. He played with a team in Cobbleskill, about 25 miles south of Fort Plain, where his batting earned him more playing time at second base. Simply being a pitcher allowed Dahlen to be in the lineup only once every few days, so a shift to a fielding position allowed more opportunities at the plate.4

Dahlen got married for the first time on January 1, 1890, just short of his 20th birthday. The wedding was held in Fort Plain. His wife, Hattie (whose family name is not presently known), was then just 15. They had a daughter the following August, named Corinne.5

When Cobbleskill became a member of the New York State League in 1890, Dahlen started his professional baseball career, though, unfortunately, the team ceased operations late that same season. Dahlen stayed in the NYSL, joining the Albany squad for its last game. His skills were unquestionable—a .343 batting average, second best in the league, and a league leading 137 hits and 18 triples.6 Dahlen’s trajectory pointed toward the major leagues. In the NYSL, Dahlen established his credentials. With the Chicago Colts, he tested them.

Bill Dahlen made his major league debut with the Colts on April 22, 1891. The Chicago Daily Tribune highlighted his rookie status that day: “The only new men in the game will be Dahlen, who is down for Tom Burns’ place on third, and Reilly, on the same bag for Pittsburg.”7 Burns was a Colts veteran, having played with the team since 1880.

In the Tribune’s recap of the game the next day, Dahlen received praise, though he remained unseasoned: “He is one of the most promising players that have ever shown in this country. He has speed, a cool head, and a splendid movement, but he has yet a deal to learn, and Tom Burns’ steady head is needed to balance the team. Thus in the eighth inning today Dahlen was on third and Cliff Carroll lifted a high fly to Fred Carroll in right. Dahlen should have taken the chance to score, as there was but one out. Instead of improving the opportunity he let it slip by, and was left on third. Had he made the break and scored the Chicagos would have won without having to play ten innings.”8

Dahlen won more praise as the season progressed. Before the Colts headed East in late May for a stretch of away games, the Tribune noted, “Dahlen has strengthened in batting wonderfully and it presents today in action as strong a front as any club ever did in the league.”9

The rookie had some misadventures in the field, as seen on July 28, when Cleveland beat Chicago. “It would rise into the air and he would flounder around like a horse with blind staggers. After he had circled around once or twice the ball would fall at his feet and the batter would land at second or third. The Cleveland grounds are worse than those on the West Side in Chicago. That is saying a good deal.”10

Dahlen’s first season was an exciting one, with realistic hopes of a National League pennant for the Colts. Led by player-manager Cap Anson, the Colts ultimately came in second to the Beaneaters.

Dahlen played with Chicago through 1898. In his sophomore season, he proved his worth as a batsman, compiling 170 hits. His batting average climbed to .293, a jump of 33 points from his rookie season. He stole a career-high 60 bases.

His best year during his Chicago tenure was 1894, when he reached career highs in batting average (.359), home runs (15), runs (150), hits (182), and RBIs (108). During the 1894 season, Dahlen hit safely in 42 consecutive games, currently ranking as the fourth-longest all-time hitting streak in the major leagues.

Dahlen hit .352 in 1896—it was the last season he cracked the .300 barrier. In addition, he achieved his third-highest number of hits and second-highest number of runs in a season—167 and 137, respectively. It exemplified Dahlen’s status as a reliable batsman. Further, Dahlen stole 51 bases, his second-best single-season total.

A reputation for difficulty began during his Chicago years, chronicled at the end of the 1898 season in a Tribune baseball summary: “Dahlen leads the league in one respect. He holds the record for being put out of games. Yesterday was his tenth enforced desertion of his team.”11

After the 1898 season, Dahlen, by now the captain of the Colts, headed to Minnesota for two weeks of duck hunting.12 This trip captured headlines when police arrested Dahlen and fellow “amateur sportsmen”—pitcher and teammate William Phyle and their friend, John T. Fanning—for killing a mule owned by a local farmer.13 Upon returning to Chicago after the mule controversy, Dahlen sensed a change in the Windy City air. “Yes. I have known from the way the wind was blowing for some time that I would not be on the team next year, and I think the same can be said of [Bill] Lange.”14

By the end of November 1898, Dahlen’s premonition became more evident. Team President Jim Hart said, “But I do know that so far as concerns my personal opinion I believe Dahlen and Lange might be exchanged for other players who would be of more service to the Chicago club. I do not say that it will be easy to get other men in their places who will be just as good ball players, but they may be of more service to the team.”15

Dahlen’s performance in 1898 was beyond adequate, contrary to what Hart insinuated. He hit .290, driving in 79 runs and scoring 96, on 151 hits, including 35 doubles. Hart expanded on his reasons, despite the statistics. “The public, while liking the ability of Dahlen and Lange, became convinced that they were at times indifferent to the success of the club,” stated Hart. “This fact was thrust upon me in countless ways, and I feel it to be only a duty to the patrons of the game to say how they feel about it.”16

Hart’s blast against the two Colts players cited a lack of teamwork, appreciation, and sacrifice. The team’s management also became an issue. Hart revealed, “I think that if Dahlen and Lange go to other clubs they will be able to appreciate the good treatment they have received in Chicago; but they do not appreciate it now.”17

Finally, on January 25, 1899. Chicago traded him to Baltimore for Gene De Montreville. Softening his earlier criticism, Hart showed decorum. “In dropping Dahlen from the roll, I do not wish to be considered in any way as reflecting upon Dahlen’s playing ability, for a more expert fielder never wore a baseball uniform,” eulogized Hart. “If he had greater ambition I do not doubt but that he would be the acknowledged star of the baseball world.”18

Certainly, Dahlen was not the only reveler on the Chicago ball club. Indeed, Dahlen, Bill Lange, Jimmy Ryan, and other members of Chicago’s notorious Dawn Patrol were ungovernable carousers whose antics and insubordination had exhausted the patience of club management. Tom Burns, by then Chicago’s manager, said, “I don’t want to be quoted as saying that I believe DeMont is a better player than Dahlen, but that I believe that he will be and that he is now a better player for Chicago than Dahlen. The exchange was made in the interests of discipline and will strengthen the team in other ways as well. If I did not think so I should not have suggested it.”19

A new ownership syndicate controlled the Baltimore Orioles and the Brooklyn franchise (then known as the Superbas) in 1899. Brooklyn was this group’s favored location, though a club continued to operate in Baltimore in 1899. Dahlen expressed resignation at joining the Superbas, indicating submission rather than enthusiasm. “Of course, I hadn’t been consulted when I was traded for DeMont,” Dahlen said. “I am expected to go wherever I am sent, and I suppose I have no recourse but to go. I haven’t seen Hart for three weeks, but have been expecting this. At the same time I am not raising any howl. The Baltimore boys are all friends of mine.”20

Though Dahlen’s statistics in 1899 fell below his 1898 numbers, they were nonetheless respectable: .283 batting average, 76 RBIs, 121 hits, 87 runs scored, 29 stolen bases. Brooklyn won the National League championship in 1899 and repeated in 1900.

Dahlen separated from Hattie in 1899, and they were divorced in 1901, amid allegations of domestic violence.21 That aside, his 1901-03 seasons were practically triplets, statistically speaking. He batted in the .260s, continued to drive in runs and remained a useful base-stealer. His behavior, however, remained an issue. After the 1903 season, Brooklyn’s team owner, Charles Ebbets, tired of dealing with it, sent him to the New York Giants in exchange for shortstop Charlie Babb and pitcher Jack Cronin. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle explained, “In the first place, Dahlen, while a great player, never was an observer of discipline. He looked upon rules from the standpoint that they were made only to be broken, and while this has in no way affected his playing ability, still the injury to the team in a disciplinary way has been great.”22

Dahlen also refused a salary cut, thereby ensuring a trade. Ebbets reinforced, “The reasons for the trade were given at length by the Eagle yesterday and I have no more to add. I will say that I hope Dahlen will have every success in his new place.”23

On the other hand, Dahlen received praise in the New York Times, perhaps because of a bias toward the Giants. “Dahlen is very fast and an earnest worker. He has given an unusually good account of himself during the last ten years. He is a ‘pinch’ hitter of the first order, he can run bases as quickly, if not more quickly, than any of his confreres, and as to fielding his position, Dahlen seldom leaves anything to be desired.”24

Shortly after those stories came out, on December 22, 1903, Dahlen went down the aisle a second time, marrying Jeanette Hoglund. Willie Keeler was Dahlen’s best man.25

Charlie Babb, Dahlen’s successor in Brooklyn, made an immediate impression on observers at spring training with his enthusiastic approach, which varied from Dahlen’s style, perceived as indifferent. The Eagle stated that Babb would be a “hit with the Brooklyn fans if only because of the ginger he puts in his practice.”26 However, Babb proved to be a bust. His playing days ended after the 1905 season. For his three years in a major league uniform, Babb notched a .243 batting average.

Dahlen spent four years in a Giants uniform, playing more than 140 games each year, and leading the NL in RBIs in 1904. That year, Giants manager John McGraw (a kindred spirit) expressed his view that Dahlen was the best shortstop in the country.27 Dahlen was an important cog in 1905, when New York won the World Series (though he went 0-for-15 in the Series). He remained the team’s starter at short for two years after that. However, his batting steadily declined from .268 to .207 from 1904 through 1907.

On December 13, 1907, the Giants traded Dahlen (by then 37) and four other players to the Boston Doves in exchange for three players. Tim Murnane of the Boston Daily Globe chronicled the deal, describing Dahlen as “one of the great shortstops in the business.”28 Dahlen played 144 games, notched 125 hits, and batted .239 in 1908. It was good enough for Doves president George Dovey to stand firm in protecting Dahlen from encroachment by Brooklyn, which wanted the aging player to manage its squad.

“I have figured that Dahlen will be back at his old place at the South End grounds next season, as I can’t see any one in sight that would fill the bill for my club,”29 said Dovey, who addressed one offer from Charles Ebbets, which may have been a conversation starter rather than a reality. Ebbets offered shortstop Phil Lewis for a trade, which Dovey dismissed as a “big joke.”30

In turn, Ebbets believed that an agreement existed, at least in principle, to send Dahlen to Brooklyn, despite Dovey’s refusal of a Lewis-Dahlen trade.31 At the National League meeting in December 1908, Dovey hired Frank Bowerman to manage his club.

Dovey put a $7,000 price tag on Dahlen, who “claims that he is entitled to his release and figured that Boston would give it to him for the asking, but Boston must have a shortstop, and Brooklyn being short on that article, it now looks as if Dahlen would have to return to the South End grounds. It will be a case of a dissatisfied player and a heap of trouble for manager Bowerman.”32

Brooklyn fans were disappointed that Ebbets could not get Dahlen to manage the club in 1909—indeed, to call it mourning may not be an exaggeration. The Eagle reported, “The suspense is so great that the thirty-third degree readers have passed beyond the letter writing habit and are now engaged in voicing their sentiments in postal card cartoons of which the accompanying, intertwined ‘Asleep at the Switch’ is a sample. What the end will be is awful to contemplate.”33

As 1909 began, Ebbets remained steadfast in his pursuit of Dahlen.34 To that end, the Brooklyn ball club owner attempted to deal with Dovey at the National Commission meeting in Cincinnati.35 Ebbets’s efforts were for naught; Dahlen wore a Boston uniform in 1909.36 It was far from a glorious year; Dahlen played in 69 games, getting just shy of 200 at-bats. He batted .234 with 46 hits.

By 1910, Ebbets got his wish, signing Dahlen as the Brooklyn skipper. Dahlen’s reputation for ferocity paved his path to Washington Park. “He was known to be aggressive, and that was certainly one feature which had been sadly lacking of late in the Superbas,”37 reported the Eagle. Further, Ebbets handed Dahlen “absolute control of the players” and authority for “all releases, purchases and trades.”38 Fans responded in the pages of the Eagle, praising Dahlen’s tenure as a Brooklyn player, knowledge of the game, and aggressiveness.39

The Superbas did improve their record in 1910, albeit modestly, to 64-90 from 1909’s 55-98. Though the club’s winning percentage improved slightly in 1911, Brooklyn dropped a notch in the standings, to seventh. Dahlen played three games in 1910 and one game in 1911.

Dahlen sought to mold his players into a team rather than acting as individuals, in contrast to his Chicago experience. Dahlen biographer Lyle Spatz wrote, “Alert to any way of improving his young team, Dahlen wrote letters to several of his veterans, including pitchers [Nap] Rucker and George Bell, asking them to report to Hot Springs early. His plan was to have these veterans work themselves into shape before the youngsters reported, and then to serve as mentors to them.”40

Dahlen also looked for temperance on his team, whereas some of his players liked to “celebrate.” “Some Brooklyn players, it appeared, were not always as circumspect in their demeanor on road trips as they should have been,” wrote Spatz.41

On the field, though, Dahlen still tangled with umpires; the beginning of the 1912 season exemplifies his pugnaciousness. In the season’s second game, which ended in the eighth inning because of rain, Dahlen argued that Giants first baseman Fred Merkle interfered with a ball in play, thereby allowing the Giants to score a run with the bases loaded. “Up came Dahlen with a loud kick,” reported the New York Times. “He argued that Merkle got in the way of the ball. Umpire Klem ruled Dahlen off, and had to get his clock out to see that he disappeared within the time limit.”42 Further, the Times recognized Dahlen’s penchant for argument: “‘Bad Bill’ Dahlen got his first warm-up for the trip from the bench to the clubhouse, which he will take many times before the season is over.”43

It took Dahlen just four days to get ejected again, prompting the Times to open its April 16 game story with a metaphor: “Keeping Bill Dahlen in the game is like trying to keep a sparrow in an open lot.”44 Dahlen argued with umpire Cy Rigler when Rigler ruled against Red Downs’s steal of second after Dolly Stark helped to “tangle up” Phillies catcher Red Dooin. Ordering Downs back to first base—which Rigler had also done earlier with Herbie Moran on first base and Jake Daubert at bat—maddened Dahlen.45

Tempers erupted less than a week later; verbal tirades became physical bouts. Dahlen got a three-day suspension for his actions, yet he escalated them in the April 20 game against the Giants. Predictably, the New York Times and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle differed in how they described what led to fisticuffs between Rigler and Dahlen. A home run for the Giants was the source of the argument—Dahlen thought it was a couple of feet into foul territory. “The perturbed Dahlen had no time to work his vocabulary up to the exploding point and was merely gesticulating and uttering general words of inquiry and condemnation when the aggrieved umpire struck him upon the right cheek,”46 stated the Eagle. The Times took a pointed tone in its account, placing the blame on Dahlen. “Defiantly, Dahlen rushed at Rigler, shaking his fist in the umpire’s face. ”47

Regardless of his early managerial promise, Dahlen never broke .500 or got above sixth place in his four-year reign. The most wins Brooklyn could muster for him was 65, in 1913. Ebbets fired Dahlen after that season, at the same time lauding his leadership. “His judgment in handling the players under contract of the Brooklyn club has been wonderful. During his first three years as manager he dispensed with the services of many players who were either incompetent, misbehaving or troublesome, rarely misjudging as a player, as is evidenced by the fact that of all the men he passed up only one was of major league caliber,” stated the Tribune.48

Wilbert Robinson replaced Dahlen, leading the Tribune to opine on their different temperaments: “Bill Dahlen haunted the umpires night and day, while, on the other hand, Robinson, mild and good natured, rarely if ever gets into a controversy with the [umpires] of the diamond.”49 Acknowledging his predecessor, Uncle Robbie said, “My task will not be too hard, either. Bill Dahlen left the foundation of a mighty strong team, and I hope to complete the task so ably started.”50

Dahlen stayed with Brooklyn as a glorified scout, but that job lasted one season. He stayed connected to baseball by attending games, as well as scouting for the Giants for a number of years.51 Dahlen did play shortstop in a 1921 benefit game for his old teammate Christy Mathewson (Matty was suffering from the tuberculosis that killed him four years later).52

According to newspaper accounts, Dahlen worked on the docks in New York City, ran a semi-pro team in Brooklyn, and owned a filling station. He also served as an attendant at Yankee Stadium for several years and as a night clerk in a Brooklyn post office.53

Dahlen’s passion for the game never diminished. The Philadelphia Phillies prompted his admiration during a Phillies-Dodgers contest in 1937. “They’re playing the ‘smartest’ baseball I’ve seen in years—using the squeeze play, the double steal and all that,” he stated. “These fellows really play as if they know there’s more to the game than just trying to knock the cover off the ball! It’s a treat to watch them.”54

Notwithstanding a mediocre record as a manager, Dahlen’s career as a player has drawn support in more recent years for Hall of Fame status. That wasn’t the case in 1936 and 1938, when he received just one vote. In 1994, though, he received support from the Hall’s Veterans Committee for the first time. That year, the Society for American Baseball Research called him one of five overlooked old-time players worthy of a place in Cooperstown. He ranked third behind Bid McPhee and George Davis, both of whom subsequently made it in.55 There is a strong parallel between Dahlen and Davis in particular.

SABR’s 19th Century Committee selected Dahlen as its “Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend” for 2012. The Society’s article cited his skills as both a great defensive shortstop and an offensive shortstop.56 Another article, from SportingNews.com in 2015, pointed to Dahlen’s strong ranking on a newer statistic: Wins Above Replacement (WAR), again in terms of both offense and defense. Behavioral issues, if they are influencing Dahlen’s selection, should not necessarily overshadow results.57

Bill Dahlen died in Brooklyn on December 5, 1950 after a long illness.58 His daughter Corinne survived him. His final resting place is a currently unmarked grave in Brooklyn’s Cemetery of the Evergreens.59

Notes

1 Lyle Spatz, Bad Bill Dahlen: The Rollicking Life and Times of an Early Baseball Star (Jefferson, North Carolina: 2004), 4, citing Washington Frothingham, History of Montgomery County, New York (Nelliston, NY: Nelliston Community Group, 1978), 174.

2 Steve Amedio, “Overlooked,” Schenectady Gazette, July 17, 1994, E4.

3 Spatz, 5.

4 Spatz, 6.

5 “Dahlen’s Wife Seeks Divorce,” New York Morning Telegraph, January 7, 1901. “Sues Dahlen for Divorce”, The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), January 4, 1901

6 Spatz, 6.

7 “Now It Is “Play Ball,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 22, 1891.

8 “Opening of the Campaign,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 23, 1891.

9 “Easily In First Place,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 24, 1891.

10 “Chicago Moving Onward,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 29, 1891.

11 “Notes of the Game,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1898.

12 “Where the Ball Players Go,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 18, 1898.

13 “Gossip of the Ball Players,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 25, 1898.

14 “Dahlen Expects To Go,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 4, 1898.

15 “Hart Favors Changes,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 29, 1898.

16 “Hart Favors Changes”

17 “Hart Favors Changes”

18 “Dahlen Now An Oriole,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 26, 1899.

19 “In Interest of Discipline,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 26, 1899.

20 “Hanlon Selects the Team,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 6, 1899.

21 “‘Bill’ Dahlen, Crack Brooklyn Shortstop, Sued for Divorce,” New York Evening Telegram, January 8, 1901. “Sues Dahlen for Divorce”.

22 “Bill Dahlen Traded For Babb and Cronin,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 14, 1903.

23 “Babb and Cronin Sign with Brooklyn,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 15, 1903.

24 “Local Baseball Trade,” The New York Times, December 14, 1903.

25 Spatz, 123, citing “Bad Bill Dahlen Becomes a Benedict,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 21, 1903

26 “Finest Weather for Practice of Superbas,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 24, 1904.

27 “‘Mild Bill’ Dahlen Great Short Stop,” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, August 12, 1904, 10.”

28 T.H. Murnane, “Big Deal Made By Joe Kelley,” Boston Daily Globe, December 14, 1907.

29 “Will Hold Dahlen,” Boston Daily Globe, November 18, 1908.

30 “Will Hold Dahlen”

31 “Brooklyn Claims Dahlen,” Boston Daily Globe, November 20, 1908.

32. “Will Hold Dahlen”

33 “Baseball Fans Tired Looking For A Manager,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 16, 1908.

34 “Ebbets After Sebring Despite Ban Johnson,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 2, 1909.

35 The National Commission existed from 1903 to 1920, consisting of a three-person committee which oversaw organized baseball. A chairperson and the presidents of the American League and the National League comprised the commission.

36 “Catcher Joe Dunn Signs With Brooklyn,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 7, 1909.

37 “Dahlen to Lead Superbas in 1910 Pennant Race,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 27, 1909.

38 “Dahlen to Lead Superbas in 1910 Pennant Race”

39 “Dahlen Is Popular,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 28, 1909.

40 Spatz, 177.

41 Spatz, 177.

42 “Giants Lose Short Game To Brooklyn,” The New York Times, April 13, 1912.

43 “Calm After the Storm,” The New York Times, April 13, 1912.

44 “Manager Dahlen In Tilt With Umpire,” The New York Times, April 17, 1912.

45 “Manager Dahlen In Tilt With Umpire”

46 “Punched By Umpire, Dahlen Hits Back,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 21, 1912.

47 “Rigler and Dahlen Fight in Ball Park,” The New York Times, April 21, 1912.

48 “Baseball Axe Cuts off Bill Dahlen: Deposed as Manager of the Brooklyn Team After Four Years,” New York Tribune, November 18, 1913.

49 “Baseball Great Booster for Towns in the West,” New-York Tribune, November 25, 1913.

50 “Ebbets Dedicates Robinson, Too,” New-York Tribune, November 21, 1913.

51 “Bill Dahlen, Fort Plain Idol of National League Long Ago, Dies,” Amsterdam (New York) Recorder, December 7, 1950, 13.

52 Spatz, 203.

53 Amedio, “Overlooked”

54 Press release, Philadelphia Phillies, May 6, 1937.

55 Amedio, “Overlooked”

56 Williams, Joe, “SABR 42: Bill Dahlen selected as Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend for 2012,” (http://sabr.org/latest/sabr-42-bill-dahlen-selected-overlooked-19th-century-baseball-legend-2012), July 2, 2012. This award is bestowed upon “a 19th century player, manager, executive, or other baseball personality not yet inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.”

57 Graham Womack, “Why has Bill Dahlen’s Hall of Fame induction taken so long?”, sportingnews.com, October 13, 2015 (http://www.sportingnews.com/mlb-news/4658077-bill-dahlen-hall-of-fame-chances-stats-chicago-colts-orphans-brooklyn)

58 “Bill Dahlen, Fort Plain Idol of National League Long Ago, Dies”

59 Spatz, 205.

Full Name

William Frederick Dahlen

Born

January 5, 1870 at Nelliston, NY (USA)

Died

December 5, 1950 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.