Don Gutteridge

His son, Don Jr., became a successful lawyer in Oklahoma City. Don Jr. and his wife, Sonya, had three sons, who presented Don and Helen with five great-granddaughters and a grandson.

In the offseason during his baseball career, Don did things to, as he put it, “put meat on the table.”2 He taught school, sold cars, worked on the railroad, and refereed football and basketball, but the thing that he was proud of is simple and something many of us would have wanted to say: “I always wanted to be a ballplayer.”3

Don Gutteridge died on September 7, 2008, at the age of 96, about a month after contracting pneumonia. When he died he was the seventh-oldest living major leaguer and the only surviving member of the 1944 St. Louis Browns, the only pennant-winner in the history of the team.

He was born in Pittsburg, Kansas, on June 19, 1912, to Joe Gutteridge, a foreman for the local railroad, and his wife, Mary. Growing up he would, he said, “bribe” his three brothers to play ball. He began as a mascot on one of the railroad teams in Pittsburg.4 He began playing in 1928, beginning a career that spanned seven decades in semipro, minor, and major leagues, and coaching and managing in both the minor and major leagues.

In Pittsburg, he played baseball four times a week in a city league. Sometimes they played teams from Wichita and Kansas City. There was no high-school baseball for Gutteridge. He played semipro baseball with a team that promoted the local railroad. There was togetherness in the relationship with his father and his brothers, which helped him a great deal. There was also togetherness with playmates who, Gutteridge said, “played baseball every chance when I was a kid.” 5

He got his break in 1932 when Joe Becker, a scout from Joplin, Missouri who worked for the Brooklyn Dodgers, signed him to a contract. Becker told Gutteridge that if he wanted to play, he could get a spot at third base for the Lincoln club in the Nebraska State League, a Class-D circuit. Becker told him, “If they ask you to play third base, say okay.”6 Gutteridge had been playing second base. He got a railroad pass from his father and began his career. In 1933, his second year in the Nebraska State League, he led the league in hitting with a .360 average.

This was during the Great Depression and times were tough. He began at $75 a month and then in 1933 his salary was cut. Gutteridge and others were making $50 a month. They were glad to have work, but it was getting financially troublesome for the Nebraska State League.7

At the close of the 1933 season, Branch Rickey came calling. Rickey, the general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, had an offer for the Nebraska State League. He would give the league $2,000 if he could take eight players — two from each team in the four-team circuit. Gutteridge was one of them. The league agreed, and Gutteridge was on his way to the major leagues as a St. Louis Cardinal.

As with many other players, Gutteridge’s relationship with Rickey was colored by money. He spent seven years in the Cardinals system in the majors and minors (1934-1940) before being let go after the 1940 season. As Gutteridge put it, “When Rickey was done with you, you were out.”8

He and Helen were married after the 1933 season. He reported to the big-league camp in 1934, but spent the next three seasons in the minor leagues. In 1934 he played with the Houston Buffaloes in the Class-A Texas League; in 1935 he began a two-year stint with the Columbus Red Birds in the Double-A American Association. In September 1936, Gutteridge came up to the Cardinals, playing in his first game on September 7. He got into 23 games and hit .319, driving in 16 runs. He’d made his mark and the next year became the regular third baseman for the Cardinals, but he never hit for as high an average again. During his 12-year career, Gutteridge hit .256 with 1,075 hits and 39 home runs. He remained in the big leagues until 1948.

When Gutteridge broke in with the Cardinals, manager Frank Frisch knew that veteran third baseman Charlie Gelbert was near the end of his career. Gelbert had recovered from a hunting accident in 1933, but he never had the ability he had shown early in his career. After Gutteridge’s first couple of games, Frisch told The Sporting News, “Did you see that kid? He’s really a Gas Houser.”9 Gutteridge knew he had arrived and was in the right place at the right time.

Gutteridge was now a member of the Gas House Gang, a bunch of players who combined shabby appearance with playing excellent baseball and a talent for playing jokes on one another. Gutteridge said, “I wanted to be like Pepper Martin.”10 Third baseman Martin himself said, in Gutteridge’s words, “Leave this kid alone, I can go play the outfield.”11

Gutteridge became friends with Martin and Dizzy Dean. There wasn’t a dull moment. They played tricks on each other, and played good baseball. Their style and ability to win made them fan favorites with many around the country. Even though the Cardinals failed to reach the World Series while he was with the club, Gutteridge played well and stuck up for his teammates. Dean often antagonized other teams and at least on six occasions got into fights, Gutteridge would lend a hand and put it this way: when Dean got into a fight, “He NEVER got hurt, but I got hit every damn one of them.”12

Baseball during the Great Depression was competitive. Gutteridge said, “You look around and know someone could get your job You played and performed because if you didn’t someone would be more than willing to take your place.” 13 Still, to Gutteridge, it was personal. He said, “I played for the love of the game.”14

He was dropped from the major-league roster by the Cardinals after the 1940 season, and it seemed that Gutteridge’s run in the big leagues was over. But Pepper Martin became manager of the Sacramento farm club for the Cardinals and he wanted Gutteridge to come along as his player-coach. Gutteridge said he was ready to leave baseball, but Pepper talked him out of it. He coached and played 171 games at third base, hitting for a .309 average in the Pacific Coast League.

When World War II broke out, Gutteridge tried three times to enlist in the military. Birdie Tebbetts and Johnny Mize both tried to get him on teams in the armed forces. But he was declared 4-F, not fit for service, each time. As he put it, he would have fallen apart if he had been let into the armed forces. He had a trick knee and a problem with his kidneys; he also had a child and that kept him down the list for the draft.15

In 1942, Gutteridge returned to the majors as a member of the St. Louis Browns. He had been released by Rickey, who, he said, told him, “You’ll never play major-league baseball again, or be on any winning ballclub.”16

Gutteridge called the Browns a “bunch of raggedy-assed guys, no college education. They just loved to play baseball.”17 They also liked to drink and have fun. He once told the St. Louis Browns Fan Club, a group dedicated to preserving the memory of the Browns: “You went out there every day and you didn’t know if your roommate was going to be there. He might be in the service. He might be in jail.”18

The Browns also suffered from poor attendance. “Some days the players outnumbered the fans,” he told the Browns Fan Club in jest. “Some days I knew everybody in the ballpark on a first-name basis. You could have fired a shotgun into the stands and not hit anyone.”19 Jest or not, the Browns’ attendance woes were real, and they resulted in the franchise eventually being sold and moving to Baltimore.

With the Browns, Gutteridge made the transition from third base to second base and had four good seasons. In 1942 he was among the leaders in the league in stolen bases, triples, and runs scored. The next year, his 35 doubles were again among the American League leaders, but 1944 was the year that Gutteridge remembers the best. He was finally in a World Series.

During this time the Cardinals were a dominant team. From 1942 through 1949, they won four pennants and three World Series, and never finished lower than second place. But Gutteridge was now with the Browns, a team that seemed always to take second billing to the Cardinals in St. Louis. However, 1944 saw them play each other in the World Series.

The 1944 Browns won the American League pennant by a single game over the Detroit Tigers. The New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox were in the race until the final weeks of the season. What helped the Browns was that they won the first nine games of the season and then hung on to maintain the lead.

They won first place with an unlikely bunch of players. The manager was Luke Sewell. “He was always an optimist,” Gutteridge said. “…If we lost four or five games in a row he’d always say we can we win the next four or five games.”20

At second base, Gutteridge played beside a valuable shortstop, Junior Stephens. Gutteridge said he believed that if Stephens had played in New York City, “He would have been in the Hall of Fame in a minute.”21 For Gutteridge, it was a pleasure to play with Stephens on defense and it made his job easier at second base. The same could be said of the Browns’ first baseman, George McQuinn, who covered a lot of ground on Gutteridge’s left.

A problem with the Browns in those wartime days was that you did not know whom you would take the field with. Denny Galehouse, a pitcher, could play when the Browns were at home but if the Browns were out of town, it was tough to use him because of his draft status. That cleared up late in the season when he learned he was not going to be drafted. Chet Laabs, an outfielder, could play only on Sundays or at night because of his job in an armament plant. Many of the other Browns were like Gutteridge, 4-F or subject to being called up only in special circumstances. Among them were Stephens and McQuinn and pitchers Nelson Potter and Bob Muncrief.

The Browns fought hard to win the pennant, while the Cardinals easily won the National League pennant by 14½ games. Playing the Cardinals meant that all the World Series games were played in the ballpark both teams used as a home field but which the Browns owned, Sportsman’s Park. In order to have more seats in the stadium, the center-field bleachers, which had been closed during the season, were opened for the Series. Gutteridge said it was tough to hit with center field occupied by fans, a difficult background for a hitter. The Browns took an early lead in the Series but they lost to the Cardinals four games to two. Gutteridge wanted to play well to show the Cardinals that they should have held on to him, but “It was not meant to be.”22 It was a disappointing experience; he hit only .143 during the Series, 3-for-21 without an RBI. He struck out five times and committed three errors.

In 1945, the Browns came in third. Don was the team’s third baseman but hit only .238. He knew that it was probably over for him as a big-league player, but Browns general manager Bill DeWitt offered him the opportunity to become player-manager of the Toledo Mud Hens, a Browns Triple-A club. He played in 70 games for Toledo in 1946 and hit .278.

He was settling into his position when the word came that the Boston Red Sox, then running away with the American League race, needed help. Gutteridge was available, so he returned to the big leagues. He was in nine games at second base, played eight games at third and was in five other games. He stayed with the Red Sox through 1947.

His memories with the Red Sox were good ones. The Sox used him at second base and third base. The team made the World Series in ’46, playing the Cardinals. Don got two hits in Game Five, helping give the Red Sox a three-games-to-two lead. He was 2-for-5 in the game, with one RBI. He’d appeared in two earlier games, but these were his only at-bats, leaving him with a .400 average. The Red Sox lost the final two games, and the Series, four games to three. When the Series ended, he was voted a half-share, which Gutteridge thought was fair. The owner of the Red Sox, Tom Yawkey, gave him enough of a bonus to make it a full share.

In 1947, Don hit just .168 in 131 at-bats for Boston. He was sold to the Pirates late in spring training in 1948 and concluded his active career with Pittsburgh with brief appearances in four games that year. The stay with Pittsburgh offered one big thrill, however, as he was on the bench with Pirates legend Honus Wagner. “When I was there he was a coach, and was in uniform every day and came to the bench,” related Gutteridge. “Of course, he was always asked questions, and we all carried on conversations with him. He was most pleasant and always available to us.” Gutteridge said Wagner would leave about the middle of the game to visit with friends at a bar. He added that Wagner had a great laugh and his only regret was that he never got an autograph from the Hall of Famer.23

Summing up his 12-year major-league playing career, Gutteridge said the three teams he played on were distinctive and so different in his experience. “The Cardinals were rough-and-tumble. They would fight you today and love you tomorrow. The Browns were a ragtag pickup team, while the Red Sox were college types and they didn’t fight.” He added that the Red Sox were very professional and businesslike.24

His playing career over, Don almost quit baseball, but an opportunity opened up and he reported to Indianapolis to play under Al Lopez. Lopez needed a third baseman to play for the Indians, a Pittsburgh farm club. Gutteridge was the man. Indianapolis won the pennant and went on to win the 1949 Little World Series from Montreal. Gutteridge worked with Lopez for most of the rest of his career.

From 1949 through 1951, he was a player-coach for Indianapolis. In 1951 Lopez became manager of the Cleveland Indians, and Gutteridge took over as Indianapolis skipper. In 1952 he went to manage Colorado Springs of the Class-A Western League. It was a farm club of the Chicago White Sox, and Gutteridge maintained his affiliation with the White Sox through 1970.

Frank Lane, then general manager of the White Sox, wanted Gutteridge to manage what Lane called his “young kids.” Gutteridge managed the Colorado Springs team for two years. They were near the top of their league, losing the 1952 pennant on the last day of the season, but reversing matters in ’53 to win the flag on the last day.

In 1954 Don went to Memphis as manager and was promoted back to the big leagues in 1955 when he became the first base coach for the White Sox under new manager Marty Marion. Marion was fired after the 1956 season, and his coaches were in limbo. But Al Lopez, the new manager of the White Sox, said all of the coaches could come back and he wanted them back.

Gutteridge said the combination of Lopez and coaches Johnny Cooney, Ray Berres, Tony Cuccinello, and himself “were envied by quite a few other coaches around the majors.”25 They worked together as a group for eight years with the White Sox (1957-64). They would eat together, went out with their wives, they worked on strategies. Gutteridge said, “These were good years.”26

Lopez had put together an excellent coaching staff. He finished no lower than second place in his first nine seasons with Cleveland and Chicago. Though he won two pennants, he never won a World Series. He always commanded respect. Dick Donovan said it best, “Lopez was the best manager I ever played for. In fact, he was the best manager in baseball all during my career.” Gutteridge added, “Lopez was a great manager. He was always ahead of his game, and he never raised his voice.”27

Lopez ran the ballclub. John Cooney was his bench coach. Tony Cuccinello was third base coach and Gutteridge was the infield coach and coached at first base. Ray Berres rounded out the staff as pitching coach. Gutteridge called Berres the “best I’ve ever seen” in working with pitchers.28

The culmination of Gutteridge’s career came in 1959, when the White Sox won their first pennant in 40 years. Chicago’s Mayor Richard Joseph Daley, a longtime Sox fan, set off the air-raid sirens to honor the team. The problem was that some folks thought it was the beginning of World War III, and not the White Sox winning the American League pennant.

The White Sox lost the 1959 World Series to the Los Angeles Dodgers, four games to two, but for Sox fans it was a special season. During that year the team featured five future members of the Hall of Fame: Lopez, Nelson Fox, Luis Aparicio, Early Wynn, and Larry Doby.

In 1966 Lopez retired and Eddie Stanky became the skipper. Tony Cuccinello, Ray Berres, and Don were kept on by the team (Cooney had retired after the 1964 season), but the coaches didn’t see eye to eye with Stanky. It was simple: They weren’t the coaches that Stanky wanted. At the end of the season, Cuccinello and Berres quit and Gutteridge was fired. 29

In 1967 the White Sox front office appointed Don manager of the Indianapolis Triple-A team. The Indians finished second in the American Association. He was set to return the next year, but the team was relocated to Honolulu. Helen was dead set against it. But the Kansas City Royals came calling and he became the head scout for the expansion team that would take the field in 1969.

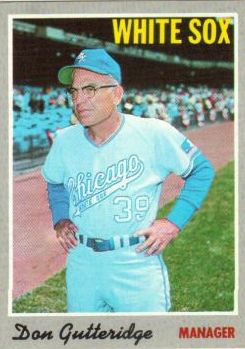

Shortly after the 1968 draft, Gutteridge left the Royals to return to the White Sox as a coach under Lopez, who had had agreed to return as manager when Stanky was fired in midseason. Lopez had retired after the 1965 season because of health problems, and when the problems returned early in the 1969 season, Lopez stepped aside again and the Sox asked Gutteridge to take over as manager. He managed the White Sox until late in the 1970 season. Gutteridge’s teams never contended and he ultimately was fired, but his association with baseball did not end. From 1971 to 1974 he scouted for the New York Yankees and from 1975 to 1992 he scouted for the Dodgers.

Gutteridge summed up his career in saying, “I was at the right place at the right time and had a good career.”30 He credited an experience he had when he was 12 years old. “We would have revival meetings. … I went to the preacher after the service and told him how much I wanted to be a ballplayer,” Gutteridge said. “He told me to talk to the Lord, and I did. I prayed to spend my life in baseball and my prayers were answered.”31

In retirement, Gutteridge took an interest in youth baseball in Pittsburg. Just before his death, the JL Hutchinson League renamed its intermediate league (ages 13-15) the Don Gutteridge League. He and a longtime friend, Todd Biggs, wrote a booklet, Getting Started in Baseball: A Guide to Learning and Teaching Baseball in the Early Years, and distributed copies to all the players in the league.

“Don had a positive impact on every single person he ever met,” Biggs told the Morning Sun in Pittsburg. “No matter how long your conversation is, whenever you left his company, you always felt better about yourself.”32

For someone who was in the right place, Gutteridge won plenty of honors. He is in the Kansas, Missouri, and Columbus (Ohio) Halls of Fame. He is a member of the St. Louis Browns Hall of Fame. A softball and baseball facility in Pittsburg is named in his honor. Early in life, he had set some goals: “I married my wife, Helen. I became a professional baseball player and made it to the World Series.”33 Not bad for somebody who “just wanted to be a ballplayer.”

An earlier version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

Sources

Interview with Herb Crehan, author of Red Sox histories and player profiles.

——: The Baseball Encyclopedia, Ninth Edition.

Cicotello, David, and Angelo J. Louisa, editors. Forbes Field: Essays and Memories of the Pirates’ Historic Ballpark, 1909-1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007).

Gough, David, and Jim Bard. Little Nel: The Nellie Fox Story (Alexandria, Virginia: D.L. Megbec Publishing, 2000).

Notes

1 Interviews with Don Gutteridge on November 11, 2006, and May 27, 2008.

2 Gutteridge interviews.

3 Ibid.

4 Don Gutteridge with Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman, From the Gas House Gang to the Go-Go Sox: My 50-Plus Years in Big League Baseball (Dunkirk, Maryland: Pepperpot Productions, 2007), 376.

5 Gutteridge interviews.

6 Ibid.

7 Gutteridge-Joyner-Bozman, 379.

8 Gutteridge-Joyner-Bozman, 99.

9 Red Byrd, “Gutteridge, Gas House Gang’s New Slugger, ‘Intends to Lead the N.L. in Thefts This Season,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1937: 10.

10 Gutteridge interviews.

11 Ibid.

12 Gutteridge-Joyner-Bozman, 33.

13 Gutteridge interviews.

14 Ibid.

15 Gutteridge-Joyner-Bozman, 104.

16 Gutteridge-Joyner-Bozman, 102.

17 Gutteride interviews.

18 Richard Goldstein, “Don Gutteridge, 96, Player for Famed St. Louis Teams, Is Dead,” New York Times, September 9, 2008.

19 Gutteridge interviews.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24Ibid.

25 Gutteridge-Joyner Bozman, 323.

26 Gutteridge interviews.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Gutteridge-Joyner-Bozman, 325.

30 Gutteridge interviews.

31 Ibid.

32 Don Gutteridge obituary, Pittsburg (Kansas) Morning Sun, September 13, 2008

33 Gutteridge interviews.

Full Name

Donald Joseph Gutteridge

Born

June 19, 1912 at Pittsburg, KS (USA)

Died

September 7, 2008 at Pittsburg, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.