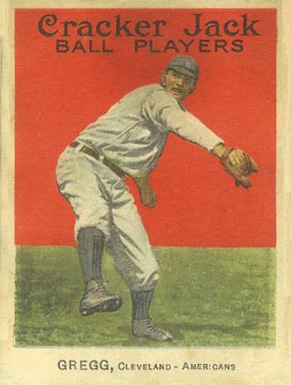

Vean Gregg

At 6′ 2″ and 180 lbs, Vean Gregg was a lanky, loose-jointed southpaw who had a world of confidence, a wicked curve ball, and a roller-coaster career hampered by arm injuries. As a 26-year-old rookie for the 1911 Cleveland Naps, Gregg was only three years removed from pitching in the deepest bush of the remote Pacific Northwest when he won 23 games and led the American League with a 1.80 ERA. Both Ty Cobb and Eddie Collins called him the best left-hander in the league, and Hall of Fame umpire Billy Evans said Gregg was “one of the greatest southpaws I ever called balls and strikes for.” The only twentieth-century pitcher to win at least 20 games in his first three years in the major leagues, Gregg is Cleveland’s career won-lost percentage leader (with a minimum of 100 decisions). Traded by the Naps in 1914 to the Boston Red Sox, where he floundered and was eventually demoted to the minors, Gregg retired after pitching for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1918. Out of the game for three years, he staged a comeback, and after a six-year absence made a miraculous return to the American League at the age of 40. A legendary minor league pitcher, Gregg won 224 games in 15 seasons of organized professional baseball.

At 6′ 2″ and 180 lbs, Vean Gregg was a lanky, loose-jointed southpaw who had a world of confidence, a wicked curve ball, and a roller-coaster career hampered by arm injuries. As a 26-year-old rookie for the 1911 Cleveland Naps, Gregg was only three years removed from pitching in the deepest bush of the remote Pacific Northwest when he won 23 games and led the American League with a 1.80 ERA. Both Ty Cobb and Eddie Collins called him the best left-hander in the league, and Hall of Fame umpire Billy Evans said Gregg was “one of the greatest southpaws I ever called balls and strikes for.” The only twentieth-century pitcher to win at least 20 games in his first three years in the major leagues, Gregg is Cleveland’s career won-lost percentage leader (with a minimum of 100 decisions). Traded by the Naps in 1914 to the Boston Red Sox, where he floundered and was eventually demoted to the minors, Gregg retired after pitching for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1918. Out of the game for three years, he staged a comeback, and after a six-year absence made a miraculous return to the American League at the age of 40. A legendary minor league pitcher, Gregg won 224 games in 15 seasons of organized professional baseball.

Sylveanus Augustus Gregg was born on April 13, 1885, near the town of Chehalis in Washington Territory, the third of nine children born to Charles Carroll and Mary Adelia Gregg. Charles Gregg had pioneered west in 1876 from his native Pennsylvania to Chehalis, a small town south of Olympia near Mount Rainier. There he met and married Chehalis native Mary Phillips in 1880. The Greggs were farmers, although Charles supplemented his income by engaging in plastering jobs. In 1896 the Greggs moved their farming and plastering operations first to Lewiston, Idaho, and then eight months later across the Snake River to Clarkston, Washington. By the time Charles died in 1913, his Clarkston cherry orchard was one of the largest in the Lewis-Clark valley. (See also: Dave Gregg)

Although Vean attained a bookkeeping diploma from the Clarkston Commercial School in January 1904, he chose to follow in his father’s footsteps and make his living as a plasterer. He later credited years of “trowel wielding” for developing the strong hands that snapped off his sharp-breaking curve ball.

Gregg initially made a name for himself as a pitcher by winning amateur and semi-pro games in the Palouse region of eastern Washington. By the time he was 23 years old, he was a sandlot star, a hired gun pitching for numerous town, semi-pro and college teams. (He remains the only major leaguer to have pitched for South Dakota State University.) An obvious candidate for organized professional baseball, Gregg delayed pursuing it because he felt he could earn more money plastering during the week and pitching for $25 a game on weekends. “I did not go into professional baseball any sooner because I could make more money outside than I could inside,” Gregg later explained. “In my semi-pro days I played baseball all over Washington, Montana and Idaho. On these barn-storming tours a player can often make more money than he could as a member of a regular league.”

In March 1908 Gregg relented and attended a tryout with the Spokane Indians Northwestern League team. He impressed the Indians’ management, but apparently did not care for the team’s offer. After pitching a few early-season games for an industrial league team in Spokane, Gregg finally made his organized professional baseball debut in the short-lived Class D Inland Empire League in June. Pitching for the Baker City (Oregon) Nuggets, Gregg won seven of eight games, dominating a circuit which included the likes of future major leaguers Jack Fournier, Pete Standridge, Les “Tug” Wilson, and Tracy Baker.

In 1909 Spokane manager Bob Brown was able to sign Gregg for $185 a month. In a season when the Spokane team won 100 games and finished 34 games over .500, Gregg’s won-lost record was a mysterious 6-13. He had a knack for losing close contests, but mainly was ineffective due to arm problems suffered from “practicing too much.” However, after watching two of Gregg’s better games, Cleveland scout Jim “Deacon” McGuire, outbidding Pittsburgh and Detroit, bought Gregg from Spokane for $4,500 and two players. This was reportedly the largest amount ever paid for a player from the West Coast. At the time his contract was purchased on July 8, 1909, Gregg’s record was just 3-6 but he had struck out 82 batters over his past eight games.

Seeming a bit indignant and unappreciative of an opportunity, Gregg refused to sign a $250 a month contract offered by Cleveland for 1910. Sold on option to Portland, Gregg had a breakout, historic season. He won 32 games, including a record 14 shutouts, struck out 379 batters in 387 innings, and hurled four one-hitters and a no-hitter. His best game came on August 16 against Portland’s main pennant rival, the Oakland Oaks, when Gregg struck out 16 batters in a twelve-inning, one-hit shutout. In the no-hitter at Portland’s Vaughn Street Ballpark on September 2, Gregg won 2-0 and struck out 14 Los Angeles Angels, including eight men in a row, only one of whom managed even to foul a pitch. Behind the strong arm of Gregg, the Beavers won the Pacific Coast League championship. Years later, whenever old West Coast sportswriters or ballplayers were asked to pick their all-time PCL teams, inevitably they would include Vean Gregg based upon his dominating 1910 season. Even the local census taker was impressed; that year he listed Gregg’s occupation as “star pitcher.”

In 1911 Gregg joined a “disorganized” Cleveland team that included a very old Cy Young, an aging but still productive Napoleon Lajoie, and a 23-year-old Joe Jackson, who hit an astounding .408 that year. Finishing under .500 and in the second division the year before, the Naps lost revered right-hander Addie Joss when he took ill and died on April 14. However, the team overcame that setback and improved under interim manager George Stovall, finishing the season with a winning record and in third place.

One day shy of his 26th birthday, Gregg came out of the bullpen and made his major league debut on April 12, 1911, at St. Louis, giving up three runs in four relief innings while also hitting a double. After striking out Detroit’s Sam Crawford twice in a second relief appearance six days later, Gregg moved into the starting rotation and won his first start, 5-2, against Chicago. By mid-July he was the talk of the American League. When he beat Philadelphia on July 27, he won his tenth consecutive game and ran his record to 18-3. After winning a July game against New York, Hal Chase called Gregg “the leading pitcher of the league, and in my opinion, the most marvelous southpaw I have ever looked at.”

Gregg’s pitching motion was described as “a free and easy delivery, and his wind-up is a graceful sweep above the head that bothers the batters not a little.” In addition to throwing overhand, he would mix in “an under-hand toss and cross-fire for variety.” While his fastball was described as “good,” he was known for his curve ball, a pitch that “drops between three and four feet in a space of eight or ten feet, possibly less.” Gregg had such good control of his curve ball that he would not hesitate to throw it with the bases loaded and a full count on the batter.

Whether it was the strain of throwing too many curve balls, or “practicing too much,” or throwing too many innings for Portland, Gregg experienced recurring arm pain over the years. He would have periods where the arm “never felt better,” but would also suffer through entire seasons where he was a shadow of his former self. With a good arm, he was very, very good. With a bad arm, he sat on the bench and lost opportunities.

Gregg’s arm was sore the latter part of his rookie season, and after beating Chicago 9-2 on September 4 he did not pitch again. He went home to Clarkston in early October, missing the Naps postseason series with Cincinnati. In addition to leading the league in ERA, Gregg also led the circuit in fewest hits per nine innings. He was especially adept at beating Chicago, besting the White Sox seven times without a loss during the 1911 campaign, including three wins where he matched up against Sox ace Ed Walsh. Named in The Sporting News as a member of the “all-American League” team, Gregg received a $500 bonus from the Naps, bringing his total 1911 salary to $2,600. “Unless something unexpected happens,” the Chicago Tribune wrote, “he promises to take a place among the great left-handers of baseball history.”

After much off-season dickering, Gregg finally agreed to a 1912 contract calling for $3,500, plus a $1,500 bonus should he win 25 games. With sporadic arm soreness and visits to the noted chiropractor Bonesetter Reese, Gregg managed to win 20 games. While Cleveland retrograded to a sub-.500 fifth-place team in 1912, Gregg continued to impress, even with a sore arm. Naps manager Harry Davis, who tired of a bickering, faction-torn team and resigned a month before the end of season, claimed, “That fellow Gregg is an exact duplicate of Waddell when the Rube was at his best.”

Gregg had his last outstanding season in the major leagues in 1913. He started the season off underweight, the result of illness during spring training, but by June he had regained his strength and ran off 32 consecutive scoreless innings, beating Boston, Philadelphia, Washington and Detroit during the streak. When Gregg beat the league-leading A’s and Chief Bender on August 17 in front of the largest crowd in League Park history, the Naps were in second place, only 5½ games back of Philadelphia. However, arm soreness again crept its way into Gregg’s season. He struck out Ty Cobb three times on September 4, only to lose when Cobb drove in Sam Crawford with the game winner in the twelfth inning. With his arm growing lamer as the season entered its final stages, Gregg became a 20-game winner for the third time on October 1, beating the Tigers 8-1. But it was too little, too late, and the Naps ultimately faded to a third-place finish under new manager Joe Birmingham.

That fall, in a postseason series with Pittsburgh, Gregg’s arm came back to life. He beat the Pirates in the second game, 2-1, in eleven innings, striking out nine. Then, on October 13 at Forbes Field, he may have pitched the best game of his career. In a pitcher’s duel with Claude Hendrix that went 13 innings and tied the best-of-seven series at three games apiece, Gregg scattered five singles, struck out the unheard of total of 19, including Honus Wagner twice, and doubled and scored the game’s only run. Cleveland manager Birmingham and former manager Lajoie called it the greatest game a Cleveland pitcher had ever thrown, including Joss’s perfect game and Bob Rhoads‘s no-hitter. Home plate umpire Bob Emslie said, “I have seen all of the great ones; Rusie, Radbourne, Mathewson; but I am confident that I never saw any pitcher show the stuff that Gregg had.” Dots Miller, the Pirates’ first baseman said, “I can’t understand how anyone ever hits that fellow.”

In the spring of 1914 the Federal League war wreaked havoc on the diminishing finances of Cleveland owner Charles Somers. Losing ace right-hander Cy Falkenberg to the Feds, Somers did not want to lose Gregg, too, and signed him in March to a reported three-year $8,000 contract. When Gregg’s balky left arm reared its head and his disposition turned surly playing for a poor team, Somers decided to reduce his risk and on July 28 traded Gregg to the Boston Red Sox for three players. On a last-place team which had won only 30 of 91 games, the sore-armed Gregg had still managed a 9-3 record.

Gregg, while well paid, spent the next two and a half seasons dealing with his sore arm and stewing on the Red Sox bench. He won a total of nine games for Boston during that time and was an afterthought on a team that won the World Series in both 1915 and 1916. In 1917 Gregg was optioned to Providence, where he had one of the finest seasons in International League history, winning 21 games and leading the league in ERA and strikeouts.

In one of Connie Mack‘s infamous sell-offs, Gregg, who had been brought back to Boston after the 1917 season, was traded with two players and $60,000 cash to the Philadelphia A’s for Joe Bush, Wally Schang, and Amos Strunk. Making his first comeback to the majors, Gregg suffered along with a poor A’s team in 1918, posting a 9-14 record. When the season was cut short by the World War I work-or-fight order, Gregg, who was too old to serve, went to the Alberta, Canada, ranch he had purchased in 1912 and dropped out of the game for three years.

When crop prices hit rock bottom in 1921, Gregg abandoned the farm and decided to get back into baseball, returning to the league where he never failed. Pitching for the Seattle Indians he solidified his esteemed standing in Pacific Coast League history when he won 19 games in 1922, led the league in ERA in 1923, and in 1924 won 25 games to lead Seattle to its first-ever PCL championship. Pitching as he had for Cleveland over ten years earlier, the 39-year-old Gregg became the object of a bidding war. Clark Griffith and the Washington Senators won, paying $10,000 and giving three players to Seattle. In a repeat performance from his halcyon days with Cleveland, Gregg was a holdout in the spring of 1925.

Gregg was described as “attempting an experiment that is absolutely original. No other hurler ever attempted a major league comeback – his second at that – at such an advanced age.” Working mostly out of the bullpen for Griffith’s Senators in 1925, Gregg pitched in 26 games for the repeat pennant-winners, winning two, losing two, and saving two games. Although he performed admirably in the role he was assigned, Gregg was optioned to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association before the end of the season and did not participate in the 1925 World Series against Pittsburgh. In nine games at New Orleans, Gregg won three and lost three.

Traded to Birmingham for the 1926 season, Gregg chose to retire rather than play for the Barons. Except for a brief comeback in the spring of 1927 with the Sacramento Senators of the PCL, the remainder of his pitching career, which lasted until 1931, took place in his home state of Washington in the highly competitive semi-pro Timber League. When he was not dazzling the fans of the Timber League towns with his famous curve ball, he was exploring the great Pacific Northwest outdoors where he was known as an expert hunter and fisherman. “I am especially interested in hunting and spend a part of each year looking for game,” he said. “It is a great sport. There is none like it, not even baseball.” After his first wife divorced him in 1926, Gregg remarried and raised a family in Hoquiam, Washington, where for 37 years he owned and operated The Home Plate, a multipurpose establishment that featured sporting goods, cigars, and a lunch counter.

Suffering from prostate cancer, Gregg died at the age of 79 on July 29, 1964, in a convalescent home in Aberdeen, Washington. He is a member of the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame, the Portland Beavers Hall of Fame, the Washington State Sports Hall of Fame, the Inland Empire (eastern Washington) Sports Hall of Fame, the Northwest Baseball Old-Timers Association Hall of Fame, and in 1969 was voted by the Cleveland fans as the greatest left-handed pitcher in Indians history.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Total Baseball, 7th ed. (Total Sports Publishing), c. 2001.

Baseball-Reference.com

BaseballLibrary.com

The Vean Gregg family scrapbooks, coupled with the generous assistance, cooperation, and reminiscences of Vean Gregg, Jr.

Clarkston Republic (WA), 1907-1913, coupled with the assistance and cooperation of the staff at the Asotin County Historical Society, Asotin, Washington.

The staff of the Nez Perce County Historical Society (NPCHS), Lewiston, Idaho, and particularly the research of SABR member Dick Riggs, who in 1998 published an article on Vean Gregg in the NPCHS newsletter (“The Golden Age,” Vol. 18, No. 1).

Spokane Spokesman-Review, 1908-1909.

Baker City Herald (OR), June and July 1908.

Wallace Daily Times (ID), July and August 1908.

(Portland) Oregonian, 1910.

“Gregg Makes Great Record.” Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1910, pg. 16.

Cleveland News, Cleveland Leader and Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1911-1914, procured by SABR member Fred Schuld, who exhibited tremendous generosity and dedication to this endeavor.

Sporting Life, 1909-1917.

The Sporting News, 1909-1918, 1922-1925.

Washington Post, 1911-1916, 1918, 1925.

New York Times, 1911-1916, 1918, 1925.

Soden, E.D. “The Star of the Pacific Coast.” Baseball Magazine, December 1912, pgs. 57-61.

Marshall D. Wright. The International League: Year-by-Year Statistics, 1884-1953. McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998, pgs. 199-200.

Billy Evans. “Vean Gregg, at 39, Is Sensation of Coast League.” St. Louis Times, September 6, 1924, pg. 9.

Carlos Bauer, compiler. The Coast League Cyclopedia. Baseball Press Books, 2003.

F.C. Lane. “Vean Gregg Stages A Unique Comeback.” Baseball Magazine, July 1925. pgs. 349-350.

Eddie Collins. “Eddie Collins Fans for Stove League; His 21 Years in Game.” New York World, January 14, 1927.

Bob Ray. “Loss of Premier Ringers Muffles Mission Bells.” Los Angeles Times, March 22, 1927, pg. B3.

Aberdeen Daily World, 1926-1964.

Unreferenced and undated clippings and information from Vean Gregg’s player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame, provided along with other pertinent data by SABR member Dick Thompson, who was more than willing to share this information.

Kind assistance provided by the following SABR members:

Gene Delisio

Gabriel Schechter

Dave Eskenazi

Steve Steinberg

Bob Schaefer

Full Name

Sylveanus Augustus Gregg

Born

April 13, 1885 at Chehalis, WA (USA)

Died

July 29, 1964 at Aberdeen, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.