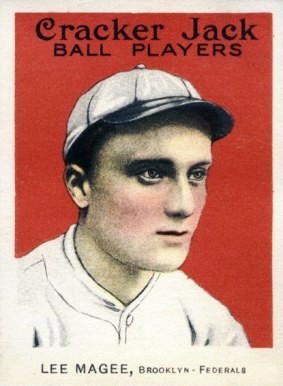

Lee Magee

The cover photo on the Sunday magazine insert of the June 29, 1958, edition of the Columbus (Ohio) Citizen was of a young boy wearing a Little League baseball uniform gazing admiringly at an older, bespectacled gentleman who was squatting, a baseball bat in hand. As the accompanying article explained, the man in the photo was the boy’s grandfather, former major leaguer Lee Magee, a veteran of nine big-league seasons and now a Columbus resident and business owner with a large family. The article, written by veteran sports reporter Tom Keys, fairly accurately described Magee’s playing career, portraying a man who valued family above all else.1 However Keys’ article completely failed to tell readers the rest of the Lee Magee “story,” omitting any mention of a career that did not end voluntarily, but rather in controversy and litigation that barred the player for life from the game he loved. Any discussion of the enigmatic Magee is incomplete without it.

The cover photo on the Sunday magazine insert of the June 29, 1958, edition of the Columbus (Ohio) Citizen was of a young boy wearing a Little League baseball uniform gazing admiringly at an older, bespectacled gentleman who was squatting, a baseball bat in hand. As the accompanying article explained, the man in the photo was the boy’s grandfather, former major leaguer Lee Magee, a veteran of nine big-league seasons and now a Columbus resident and business owner with a large family. The article, written by veteran sports reporter Tom Keys, fairly accurately described Magee’s playing career, portraying a man who valued family above all else.1 However Keys’ article completely failed to tell readers the rest of the Lee Magee “story,” omitting any mention of a career that did not end voluntarily, but rather in controversy and litigation that barred the player for life from the game he loved. Any discussion of the enigmatic Magee is incomplete without it.

That Magee should reside in Columbus in later years is not all that surprising. He was born to Joseph and Mary Hoernschemeyer on June 4, 1889, in Cincinnati, just a couple of hours away. His parents were of German ancestry; his father was a grocer. Birth records list Leo F. as their son’s given name and middle initial at birth,2 but at some point thereafter he became known as Leopold Christopher. A 14-letter surname was unwieldy, particularly for someone whose name began regularly appearing in baseball box scores. Leo thus mercifully adopted the last name “Magee.” In January 1917, after many years of unofficial use, he legally changed his name to Leo C. Magee.3 By then he was known in baseball circles as Lee Magee.

Magee cut his baseball teeth on the sandlots of Cincinnati, particularly the diamond at the Liberty St. Bottoms. “Our team would show up at the Bottoms at 10 o’clock in the morning to hold the diamond for the game scheduled for 2 o’clock,” he told the writer of the Columbus Citizen article.4 For a time he was a batboy for the Cincinnati Reds. He graduated to professional baseball in June 1906 at the age of 17 when he signed a contract with the Meridian (Mississippi) White Ribbons of the Class D Cotton States League.5 Shortly thereafter he was granted his unconditional release due to a dispute over wages, the first of many such clashes during his career. In 1907 he began the year with Springfield (Illinois) of the Class B Three-I League. However he was soon either sold or transferred to Burlington of the Class D Iowa State League. In midseason he was released and subsequently signed by the Waterloo Cubs of the same league.6 Despite the turmoil Waterloo’s new second baseman was not bashful. “I figured I was a pretty hot player.”7

During the remainder of 1907 and through 1908, the popular Magee remained with Waterloo, raising his paltry .193 average 26 points in season two as his team finished first for the second straight time.8 Magee, a “star find,” according to one local paper,9 was deemed the fastest Waterloo player ever.

The speedy Magee played for the Class B (Northwestern League) Seattle Turks in 1909. While there he began to show his versatility by trying his hand at first base and becoming a switch-hitter. His .264 batting average in 150 games for the pennant-winning Turks was 12th in the league, his 48 stolen bases sixth.10 During the 1909 season his rights were sold to the St. Louis Cardinals. He reported to them in 1910, but was optioned to the Louisville Colonels of the Class A American Association in May. The Cardinals reportedly had concerns about the youngster’s hitting and fielding ability, particularly at shortstop, where he was tried and beaten out by another rookie, Arnold Hauser.11 “I was riding the bench so they sent me to Louisville,” he told Tom Keys.12 Magee played in 132 games for the last-place Colonels, batting only .215 to justify the Cardinals’ hitting concerns.

Mediocre numbers at Louisville aside, Magee debuted with the St. Louis Cardinals on July 4, 1911. In game two of a doubleheader he was inserted at second base for veteran Miller Huggins by manager Roger Bresnahan in an 11-1 loss to the Pirates at Pittsburgh. He singled off pitcher Claude Hendrix in two at-bats. A week later Magee and his new teammates were spared injury when their two Pullman cars remained on track during a serious train wreck near Bridgeport, Connecticut, in which 14 people died. The Cardinals were deemed heroes for their efforts in assisting the 47 other injured passengers.13

For his first season in the majors Magee appeared in 26 games, mostly at second base with a few at shortstop. At 5-feet-11 and 165 pounds, Magee hit .261 with 8 RBIs. The Cardinals liked what they saw. In early 1912 the veteran Huggins was injured. Magee, who was a typesetter for a Cincinnati newspaper during the offseason, took his place at second and played well, so well that when Huggins returned Magee was moved to left field, where he became a regular. Along the way he picked up the nickname “Flash.”14 In 128 games – 85 in the outfield – he batted .290. Only Huggins and Ed Konetchy were better for the sixth-place team. Magee also stole 16 bases and knocked in 40 runs. As the season wound down, he fashioned an 18-game hitting streak.

Magee’s career was marred by frequent run-ins with umpires and opponents. In the October 1912 St. Louis city series against the crosstown Browns, Magee charged and shoved umpire Joe O’Brien. Many more such incidents would follow.15 In 1913 the task of reining in Magee fell to new Cardinals manager Miller Huggins. The pair clashed early on when Magee held out for a boost in salary promised him by former skipper Bresnahan. On March 24 reports indicated that the Cardinals’ offer of $3,200 left the parties $400 apart.16 By the 29th Magee was signed and sealed for an undisclosed sum. Early in the season he showed some rare firepower, hitting the first two home runs of his career, the latter a grand slam off Pittsburgh’s Marty O’Toole on April 20 at Robison Field in St. Louis.

A bizarre incident occurred at the Polo Grounds in New York on July 17. Magee and teammate Ted Cather, a reserve outfielder, were ejected from a game with the Giants for fighting – with each other.17 On the whole, however, Magee continued to solidify his career in 1913, batting .267 in 137 games, mostly in left field. While he stole 23 bases, he was thrown out 26 times. After the season Magee and teammate Ivey Wingo were part of a group of National League players assembled by New York Giants manager John McGraw to play a series of exhibition games stateside, then embark on a world tour playing games along the way against a squad of American Leaguers chosen by Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. During one of the exhibition games, played in a pouring rain in Medford, Oregon, on November 17, Magee, playing left field, made news when “on the dead run [he] picked a ball out of the atmosphere with one hand while holding an umbrella over his head with the other.”18

The tour left North America from Vancouver by ship and included stops in Japan, mainland Asia, and Australia before sailing through the Suez Canal to Cairo. The final portion of the journey included games in Europe and ended in England. Magee kept a journal of the tour.19 He was “an ardent shutterbug,” taking a series of photographs at the numerous tour stops.20 The weary ballplayers headed home in early March 1914 on the soon-to-be infamous Lusitania. As they neared New York a number of the players, including Magee, learned via telegrams that they were now the subject of a fierce battle between the existing major leagues and the Federal League, a fledgling minor league in 1913 with wealthy owners who sought to move up to equal status with the AL and NL in 1914. Juicy contracts were in the offing for players who would jump. Magee and others met with Mordecai Brown, the former pitching star of the Chicago Cubs, now the manager of the FL’s St. Louis entry. Brown had the league’s signing rights for Magee, and made a lucrative offer. However Magee had been given the impression that John McGraw and his pennant-winning Giants were interested in making a strong bid for his services. As it turned out, McGraw was merely acting as a caretaker for the Cardinals.21 Magee ended up signing a two-year deal with the Cardinals.22 The salary was variously reported. It seems likely that the amount was $6,000 per year with a bonus incentive,23 a significant sum given Magee’s record to date but far less than the amount an angry Brown claimed to have offered him. Said Brown, who had also tried and failed to sign Ivey Wingo, “They’ll rot in their boots in organized baseball before I ever offer either one of them another contract.”24

The Cardinals’ investment in Magee proved wise, at least in 1914. Not only did the team improve to third, but Magee had one of his best seasons, playing in 142 games, primarily in center field or first base, while garnering 150 hits, both figures career highs. He batted .284 with 36 steals, also a career high and fifth best in the league. His 35 sacrifice hits led the league. Meanwhile he drew reprimands, fines, and/or suspensions at least three times. None of this curbed his increasing popularity, particularly with the St. Louis sporting press, one of whom, W.J. O’Connor, wrote, “Magee is the sort of player who looks better in a slump than most players do on the stride.”25 The love affair ended abruptly in late 1914. Magee, sensing there was still money to be made, was once again dickering with a Federal League no longer as concerned with preserving territorial rights. In November reports surfaced that Magee was meeting with the president of the Chicago Federals. Magee announced that Chicago’s offer was “almost double what I am getting here.” Cardinals president Schuyler Britton’s response: “Lee Magee can jump into the lake or the Federal League for all I care.”26

It turned out that Britton did care. Magee did not sign with the Chifeds. Instead, in mid-November he signed with the FL’s Brooklyn entry for 1915 – not only to play but also to manage. At 25 he would be one of the youngest to ever manage a major-league team.27 The managerial appointment was met with skepticism. It was also met with a lawsuit. On January 2, 1915, the Cardinals in the name of their manager, Miller Huggins, filed a petition in Cincinnati seeking a temporary injunction restraining Magee, a player they deemed still under contract for 1915, from playing in the FL.28 The petition was part of a series of similar legal maneuvers against individual players filed by the AL and NL to protect against raids on players under reserve to its member teams. The judge in Cincinnati refused to issue the injunctive relief sought by the Cardinals, indefinitely postponing the matter pending resolution of an antitrust action filed in the federal courts in Chicago in January 1915 by the Federal League against the AL and NL. The Feds sought to restrain the two leagues from enforcing contracts like the one at issue in Magee’s case. Magee quickly filed a petition to intervene in this new case.29

Meanwhile Magee was free to manage in Brooklyn. The Tip-Tops had finished fifth out of eight teams in the first season of the league’s existence as a major-league circuit in 1914.

The new manager of the Tip-Tops took his job very seriously. From the start, perhaps to allay concerns that his youth would hinder his ability to handle the veteran players on the squad, Magee took a rigid disciplinarian stance. In addition, he appeared determined to send a message to not only his players, but opponents and umpires as well, that he was a fighter who would back down from no one. As a result Magee was in constant hot water with one faction or the other from the start. In Jackson, Mississippi, during a spring-training game with the local Millsaps College squad, he engaged the college team’s catcher in a fight. That quickly involved both teams. The Tip-Tops required a police escort to exit the grounds.30 It was only the start. During his time as manager Magee was ejected on five occasions, including the first inning of the team’s home opener in April. He was thrown out an additional three times as a player.31

The Tip-Top players reacted with derision to the strict stance taken by their new manager. Before the season even started, Magee clashed with veteran outfielder Artie Hofman. When Hofman failed to follow an instruction from Magee during a spring-training game, the rookie manager retaliated by fining Hofman $10 for breaking the manager’s rule against smoking. Hofman refused to play and eventually landed in Buffalo. He was not the only unhappy Tip-Top, according to another veteran, Jim Delahanty. He predicted that a blowup was in the offing.32 Delahanty soon was gone, too. Before long even outfielder Benny Kauff, who defended Magee and was one of the league’s legitimate stars, attempted without success to jump to the New York Giants.33

The effect of Magee’s actions on his team’s performance was not immediately felt. The Tip-Tops won six of their first seven games. The success was fleeting. By the end of July the Tip-Tops were in sixth place, 10 games below .500. Manager Magee was publicly threatening to quit.34 The team’s lackluster play was not due to his on-the-field performance. Magee feasted on the league’s watered-down pitching. He finished third in the league in batting at a career-high .323. His season totals over 121 games included 34 stolen bases and a career-high 49 RBIs.

In the end it all proved too much for Magee. In mid-August, his team still mired in sixth at 53-64 and attendance suffering, the club announced Magee’s resignation as manager. According to a club spokesman, he “is young and has a fiery temper and the job has had its bad effects upon him.”35 He would continue to play second base for new manager John Ganzel, a former manager (1908) of the Cincinnati Reds. Ganzel fared only a little better (17-18) as the Tip-Tops ended the season in seventh place. It proved the last season for the Tip-Tops and the FL. In mid-December a settlement was reached with the American and National Leagues. The contracts of Magee and several other Federal League stars were taken over by oilman Harry Sinclair, until the settlement the owner of the Newark Peppers FL franchise.

A number of teams sought Magee’s services for 1916, due to his improved hitting and his versatility. In the end the New York Yankees purchased his contract from Sinclair for somewhere between $20,000 and $25,000. Magee’s pay would be in the neighborhood of $8,500, about what he was paid by the Tip-Tops.36 His old Cardinals manager Miller Huggins would be his new manager. “Well, he’s the prize of the Federal League collection,” said Huggins. “His value to a club is great when you stop to consider that he can play five positions on any club very capably.”37 Magee did shine on June 28 when he accumulated a record-tying four assists in the outfield. By season’s end, however, Huggins’ words rang hollow. Although Magee drove in 45 runs, just four fewer than in 1915, his average in 131 games fell to .257. He stole 29 bases, but he was caught 25 times. Only four AL players were caught more times. To his credit, Magee didn’t shy away when he was called upon to offer an explanation of his woes at the plate, telling a reporter, “(t)he pitching in the American league was so much better than what I faced in the Federal league that it soon convinced me that I had spent the season of 1915 in a minor league circuit.”38

In addition to his playing duties in 1916, Magee took an active role in the Baseball Players’ Fraternity, a short-lived players union. By the fall he was listed as one of six vice presidents. He also served the organization as a director and a member of its advisory board.39

After the 1916 season Magee returned to Ohio to take care of two very important personal matters. In early December the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that Magee was to marry Beatrice Albina Rodgers, described as a “popular Price Hill beauty.”40 The couple would have three children during a long marriage. And on January 8, 1917, a local judge signed an entry legally changing the ballplayer’s name to Leo C. Magee.41

The 1917 season started with Magee still a Yankee, but it was no secret they were seeking a trade. On July 15 Magee returned to St. Louis, this time to the Browns, in exchange for outfielder Armando Marsans, the Yankees agreeing to pick up the difference in salary of the higher-paid Magee. At the time of the trade Magee was batting only .220 in 51 games. Things were even worse in St. Louis. In 36 games he could muster only 19 hits and a .170 average. Given his hefty salary, more change was in order. The Browns headed in that direction in early 1918 when they reportedly offered Magee a contract for $3,500, less than half of his previous amount.42 He refused to accept the offer, claiming he had played through an injury that affected his 1917 results.43 The Browns had seen and heard enough. On March 18 they were part of a three-team deal that sent Magee to his hometown Reds. The Yankees sent outfielder Tim Hendryx to the Browns. The Reds sent the Yankees catcher Tommy Clarke.

Magee was thrilled to finally get to play in Cincinnati. His manager would be the legendary Christy Mathewson, who had sought Magee for several months prior to the trade.44 All should have gone well. It did not. One of Magee’s teammates on the Reds was Hal Chase, the first baseman known as much for his shady play as his matchless fielding prowess. It was not a good mix. While Magee’s batting average improved to .290, his fielding did not. He made a league-leading 29 errors at second base. (His 40 had led the Federal League at that position in 1915.) Moreover there were off-field problems. One on public display occurred during the Reds’ batting practice before a game with the Brooklyn Robins at Ebbets Field. One report had Magee firing a ball “with force” at outfield teammate Earle “Greasy” Neale.45 When Neale returned to the dugout, a fight broke out that left Magee bloodied. He did not return to the lineup for several games, indicating that perhaps there was more afoot than just the fight.46

As the 1918 season wound down, the nation’s war effort and not baseball was on the players’ minds. The New York Times reported that Magee had joined the war effort by way of the YMCA as “an overseas physical recreation director.”47 By the spring of 1919, the war was over and as usual Magee was battling his club over salary. When the Reds refused to increase it, he did not travel to spring training. On April 18 his contract was purchased by Brooklyn. By now many were getting fed up with Magee’s actions, but not all. Noted sports journalist Hugh Fullerton wrote, “Magee is a smart, rather brilliant fellow, whose trouble has been largely because he was accused by fellow-players of being a ‘swelled-head.’ I never have found him that way.”48

Apparently the Robins did not share Hugh Fullerton’s enthusiasm. On June 2, after 45 games and a .238 average, they shipped Magee to the Chicago Cubs for infielder Pete Kilduff. The sudden change seemed to energize Magee. Less than a month after the trade, he hit his 12th and final career home run off Wilbur Cooper of the Pirates. Playing mostly in the Cubs outfield, he batted .292 in 79 games and stole 14 bases. On August 1 he paid back the Robins with a triple and a pair of doubles in a 9-2 Cubs win. The Cubs seemed satisfied. When the Cubs released a list of players they planned to reserve for 1920, Magee was on the list. Thus it was with no little surprise that a St. Louis newspaper reported on February 12, 1920, that Magee had been waived out of both major leagues.49 The Cubs issued his unconditional release nine days later.50 The word on the street was that Magee was accused of betting on baseball games. The Cubs chose to release the player without comment rather than air the issue in public.51

Magee chose not to go quietly. On March 6 he forwarded a telegram to the sports editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch claiming that he had been unlawfully blacklisted from baseball. He threatened to file a lawsuit to test the right of the Cubs to exercise its option for his services as they did in December and then release him a month or so later. The article accompanying the text of Magee’s letter mentioned that he “was reported to have been involved in the discussion surrounding [his Reds teammate] Hal Chase, who was tried and acquitted of betting against the Cincinnati club. …”52 Those charges were heard after the 1918 season by John Heydler, the president of the NL. Attorney Robert S. Alcorn represented Chase.

Magee now retained Alcorn in late March 1920 to represent him. The pair awaited a response from Heydler to a written complaint Magee sent him. If none was forthcoming, Magee threatened to publicly air the charges against him as well as “burn my bridges and then jump off the ruins.” If no longer permitted to play, “I’ll take quite a few noted people with me. I’ll show up some people for tricks turned ever since 1906. …”53 President Heydler quickly responded to this latest salvo. He told reporters that no charges were pending against Magee and challenged him to produce his evidence of wrongdoing in the sport.54 Alcorn later claimed he gave Heydler the names of four active players who bet on baseball. Heydler categorically denied that the letter he had received from Alcorn contained the names of any such players.55 (Correspondence between the two indicates that Alcorn’s letter referred only to those players previously implicated during the Chase hearing in 1918.56)

When it became clear the Cubs and the NL would not budge, Magee filed a lawsuit against them in the state court in Cincinnati claiming $9,500 damages for breach of contract. The defendants successfully petitioned to remove the case to the federal court system on the basis that Magee resided in Ohio and the Cubs were an Illinois resident. Murray Seasongood, a Cincinnati trial attorney who later became the city’s mayor, represented the Cubs. During the pretrial phase it became clear that at trial the Cubs would claim that on February 10, 1920, Magee confessed to Cubs president William L. Veeck and to Heydler that while members of the Reds on July 25, 1918, he and Hal Chase each bet $500 against their team in the first game of a doubleheader against the Boston Braves.57 The Reds won the game, played in Boston, 4-2 in 13 innings. Magee was 1-for-6. He scored a run and made two fielding errors.

Magee’s lawsuit was tried over three days beginning on June 7, 1920, in the US District Court in Cincinnati before Judge John W. Peck. A key witness for the Cubs was James Costello, a Boston billiards-hall owner. He testified that in July 1918 Magee, and not Chase, came to him with a proposition to throw the first game of the next day’s doubleheader with Boston. The next morning Magee and Hal Chase visited Costello and renewed Magee’s offer. Costello told the pair the gamblers would not bite unless each of them had money on the game as well. Since they claimed they had no money with them, Costello agreed to take checks from each in the amount of $500. The players assured Costello that the Reds’ pitcher, Pete Schneider, was in on the fix. (As it turned out Schneider, who denied that he was part of the plot, asked to pitch the second game and not the first that day.) The players were to get even money and their checks returned if Boston won, as well as one-third of all bets collected for that game. When the Reds won the game, Costello went to cash the player’s checks. Chase’s check went through. However Magee had canceled his check.58 In June 1919 Costello brought charges against Magee in Boston Municipal Court for nonpayment. Magee was arrested but released when a settlement was reached to repay the debt. However, Magee’s connection to gambler Costello was now public knowledge.59

Both league President Heydler and Cubs president Veeck confirmed Veeck’s earlier version of events culminating in Magee’s confession of his role in the matter, although Magee had told them Chase was the instigator and not Magee. Magee, who had testified in his portion of the case, countered this strong testimony against him by taking the witness stand again, this time in rebuttal. He admitted making the bet. He denied that he and Chase planned to bet against the Reds, claiming that he was double-crossed by Chase, who bet their money against the Reds. That is why he canceled the check. Magee claimed that it was his strong play that won the game for the Reds in the top of the 13th inning. He pointed to his base hit that allowed him to score the lead run when he came home on teammate Edd Roush’s inside-the-park home run.60 That testimony had already been blunted by the earlier testimony of his manager, Christy Mathewson, who told jurors that in the ninth inning with the Reds ahead by one run, a Magee throwing error permitted Boston to tie the game. Furthermore, Magee reached first base safely in the 13th only because his easy grounder hit a stone, bounced up and struck the shortstop in the face, breaking his nose. Magee then proceeded to ignore Mathewson’s steal signal, scoring only because of the home run. Finally, he recalled that Magee threw wildly again in the bottom of the 13th inning, the Reds holding on to win in spite of the muff.61

It took the jury only 44 minutes to render a verdict in favor of the defendant Cubs. An elated John Heydler told reporters, “I consider this verdict the greatest verdict in the history of the national game in behalf of clean baseball.”62 It was only the start. A few months later, in September, a Chicago grand jury issued indictments in what is now known as the Black Sox Scandal. The decision to try Magee’s case rather than reach a settlement was but the first shot by baseball’s establishment to rid the game of its gambling problems. Emboldened by the result, the leagues took the next step.

While under cross-examination during his trial, Magee had testified, “(A) man ought to be put out of the league who would bet against his own team.”63 That became Magee’s fate, as well as Chase’s.64 Considered permanently ineligible, Magee never played a major-league game after September 28, 1919. He was 30 years old at the time. Over nine seasons he played in 1,015 games. His lifetime batting average of .276 and 1,031 hits included 12 home runs, 277 runs batted in, and 199 extra-base hits. He stole 186 bases. He played every position but catcher and pitcher.

Magee spent his post-baseball years in Columbus. He seemingly kept his baseball career, particularly the way it ended, under wraps, as evidenced by his daughter’s comments to sportswriter Tom Keys in the summer of 1958 that until recently she was unaware he had ever played major-league baseball.65 He initially worked for a finance company and played some semipro ball. Later he earned his living as the proprietor of the Commerce Coal Co., delivering coal to customers in the Columbus area. He served as a member of the Board of Trustees of Rosemont School. He died of a “coronary occlusion” on March 14, 1966, at St. Anthony Hospital, Columbus. He was 76.66 He was survived by his wife, Beatrice; a son, James Rodgers Magee; a daughter, Mrs. Joseph (Janet) M. Gallen Jr.; seven grandchildren; and one great-grandchild. Another son, Leo C. Magee Jr., died while serving in the military. Lee Magee is buried at St. Joseph Cemetery, just south of Columbus in Lockbourne, Ohio.67

Sources

Books

Allen, Lee. The National League Story: The Official History (New York: Hill & Wang, 1961, rev. ed.1965), 154-164.

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. The Biographical History of Baseball (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1995), 284.

Dewey, Don, and Nick Acocella. The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of Baseball (Wilmington, Delaware: Sport Media Publishing Inc., 2004), 305-314.

Kohout, Martin Donell. Hal Chase: The Defiant Life and Turbulent Times of Baseball’s Biggest Crook (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2001), 191-193, 227-234.

Lamb, William F. Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013), 25-27.

Archives

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Lee Magee.

Unpublished Articles

Santry, Joe. “The Lee Magee Story,” 1-4.

Notes

1 Tom Keys, “Selling Mom,” Columbus (Ohio) Citizen (magazine insert), June 29, 1958: 1, 10-11.

2 Birth Records, Cincinnati Department of Health, 1888-1891.

3 “The Short Of It: Lee Magee, Ball Player, Has But One Name Now, “Cincinnati Enquirer, January 9, 1917: 6.

4 Keys, “Selling Mom”: 10.

5 Affidavit of Leo Hoerschemeyer (sic), Federal League of Professional Base Ball Clubs v. The National League of Base Ball Clubs, et. al., U.S. District Court, Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division (File 7, 1915 Federal League lawsuit case files, sabr.org).

6 Waterloo Daily Courier, October 19, 1907: 1.

7 Keys, “Selling Mom”: 10.

8 In 1908 the Waterloo franchise, now the Lulus, played in the Class D Central Association.

9 Waterloo Daily Courier, September 14, 1908: 2.

10 Waterloo Evening Courier, November 5, 1909: 2.

11 “Lee Magee Gets Transfer to Louisville Colonels,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 18, 1910: 12.

12 Keys, “Selling Mom”: 10.

13 F.C. Lane, “The Heroes of the Bridgeport Wreck,” Baseball Magazine (September 1911): 35-38. See also Andy Piascik, “Bridgeport’s Catastrophic 1911 Train Wreck,” connecticuthistory.org.

14 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 6, 1912: 8.

15 “Cardinals Win From Browns,” Washington Post, October 10, 1912: 8.

16 W.J. O’Connor, “Ed Koney, Evans And ‘Reb’ Oakes Sign Contracts,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 24, 1913: 14.

17 “Fist Fight May Cost Cards Two Needed Players,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 18, 1913: 12. Cather apparently took offense at criticism levied by Magee over Cather’s positioning which allowed a fly ball to drop safely for a hit.

18 Joseph C. Farrell, “Giants Blank Sox in Six Rounds, 3-0,” Chicago Tribune, November 18, 1913: 16.

19 Interview with Lee Magee’s grandson, Tim Gallen, August 19, 2015, Columbus, Ohio.

20 James E. Elfers, The Tour to End All Tours: The Story of Major League Baseball’s 1913-1914 World Tour (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 32.

21 “McGraw Acting as Agent for Britton in Signing Magee, Wingo and Evans,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 19, 1914: 17.

22 Sporting Life, March 14, 1914: 3, set forth in Daniel R. Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2012), 102.

23 Chicago Tribune, November 26, 1914: 15. For 1914 the bonus was reportedly $1,200 (20 percent of his salary), based on the Cardinals’ third-place finish.

24 “Magee Will Draw $1500 More Than Manager Huggins,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 9, 1914: 14.

25 W.J. O’Connor, “Cardinals’ Rapid Improvement Due to Good Pitching,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 18, 1914: 6.

26 W.J. O’Connor, “Magee Needs Gun to Get Boost in Pay From Britton,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 3, 1914: 16.

27 W.J. O’Connor, “L. Magee May Be Youngest Boss in Big Leagues,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 24, 1914: 18. Roger Peckinpaugh was but 23 when he briefly managed the New York Yankees during the latter part of 1914.

28 “Huggins Sues to Enjoin L. Magee,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 2, 1915: 7.

29 “Lee Magee Sues to Get Same Redress as Asked in Federal League Suit,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 15, 1915: 7.

30 “Lee Magee Has Police Escort, Following Row,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 14, 1915: 15.

31 The third ejection occurred on September 23 after Magee had resigned his managerial post in early August.

32 “Brookfeds in Revolt Against Lee Magee,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 9, 1915: 17.

33 New York Times, May 4, 1915: 12. Kauff tried unsuccessfully to join the Giants again in July, at which time he spoke out on Magee’s behalf. See “Benny Kauff Quits: Issues Final Edict,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 6, 1915: 3.

34 “Magee Threatens to Quit Those Managerial Troubles,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 30, 1915: 14.

35 “Magee Resigns As Brookfed Manager,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 17, 1915: 1, quoting Federal League spokesman Hi Brewer.

36 “Magee Bought by Yanks for Big Sum,” New York Times, January 15, 1916: 11. See also St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 15, 1916: 8, and Christian Science Monitor, January 25, 1916: 20.

37 W.J. O’Connor, “Sale of L. Magee May Mean Passing of Henry (sic) Sinclair,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 15, 1916: 8.

38 “Stove League Gossip,” Atlanta Constitution, November 29, 1916: 14.

39 “The Baseball Players’ Fraternity,” Baseball Magazine (October 1916): 85.

40 “Lee Magee and Bride-To-Be,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 5, 1916: 6. Price Hill is an old Cincinnati neighborhood.

41 “The Short of It,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 9, 1917: 6.

42 J.V. Fitz Gerald, “The Round-Up,” Washington Post, February 6, 1918: 8.

43 “The So-Called ‘Iron Men’ in Baseball Are Becoming Scarce. Ask Any Hold-Out,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 7, 1918: 20.

44 “Lee Magee Is Sought by Matty for Reds,” Washington Post, November 11,1917: 21.

45 “Magee and Neale Battle on Field,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 6, 1918: 19.

46 L.C. Davis, “Sport Salad,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 9, 1918: 14.

47 “Lee Magee Joins War Workers As One Of Y.M.C.A. Physical Directors ‘Over There,’” Washington Post, September 23, 1918: 8. A later report stated Magee would go to France. New York Times, October 6, 1918: 30.

48 Hugh S. Fullerton, “Brooklyn Leads Majors In Season’s Break-Away,” Atlanta Constitution, April 27, 1919.

49 “Club Owners Raise Admission Prices,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 12, 1920: 24.

50 Atlanta Constitution, February 22, 1920.

51 J.V. Fitz Gerald, “The Round-Up,” Washington Post, February 23, 1920: 8. The waiver price at the time was $2,400. New York Times, March 25, 1920: 12.

52 “Lee Magee Wires He Will Sue for Major League Job,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 6, 1920: 12.

53 Magee Promises Real Sensation,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1920: 9. Magee later claimed he was misquoted. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 25, 1910: 24.

54 “Heyler (sic) Defies Magee to explode His ‘Biggest Bomb,’” Atlanta Constitution, March 25, 1930: 15.

55 “Heydler Awaits Startling Letter,” Hartford Courant, March 30, 1920: 10.

56 Exchange of letters between Alcorn and Heydler, March 26 and 29, 1920, Lee Magee player file, Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

57 “Says Magee Bet Against Own Club,” Boston Globe, June 3, 1920: 17.

58 “Witness Testifies Magee and Chase Bet Against Reds,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 7, 1920: 1.

59 “Witness says Magee Bet,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 8, 1920.

60 “Magee Testifies He Bet on Reds, Then Stopped Payment on Check He Gave,” New York Times, June 9, 1920: 12.

61 “Witness Testifies Magee and Chase Bet Against Reds.”

62 “Magee Loses Case in Court,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 10, 1920: 9.

63 “Verdict Against Magee Rendered in Damage Suit,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 9, 1920: 26.

64 John Thorn, “Baseball’s Bans and Blacklists,” Our Game, ourgame.mlblogs.com/2016/02/baseballs-bans-and-blacklists/, accessed February 8, 2016.

65 Keys, “Selling Mom”: 10.

66 Certificate of Death, Leo Christopher Magee, March 14, 1966, Ohio Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics.

67 Obituary, Leo (Lee) C. Magee, Columbus Dispatch, March 15, 1966: 14A.

Full Name

Leo Christopher Magee

Born

June 4, 1889 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

March 14, 1966 at Columbus, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.