July 30, 1889: Hazleton’s Jacob White Eyes competes in pitchers’ duel in Harrisburg

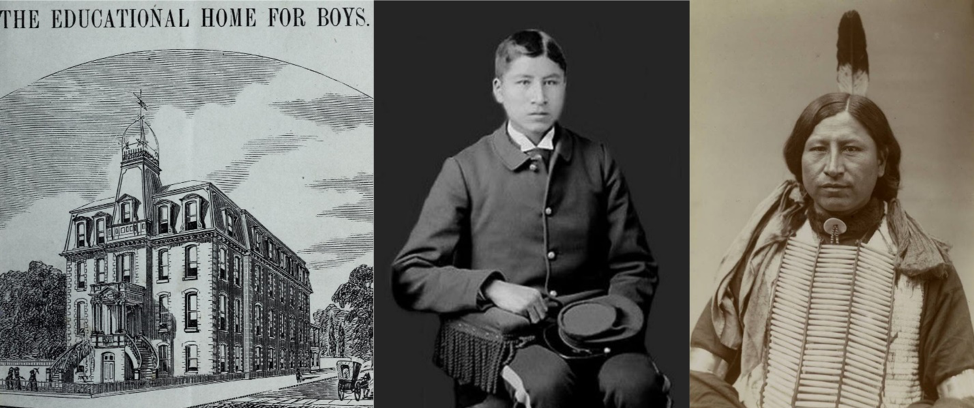

In the 1880s, the Educational Home for Boys in Philadelphia was a boarding school housing about 100 Native Americans from the Chippewa, Mohawk, and Sioux tribes.1 They learned to read, write, and speak English; obtained skills needed in farming and carpentry; and received religious and music education. “For after taking away the lands and hunting-grounds of the Indians,” said the Philadelphia Times, “it is as little as we can do to give their children the advantages of civilization.”2

Part of the boys’ training was to learn the national game. The school baseball team played against other amateur teams in Philadelphia. In 1888 and 1889, Jacob White Eyes was the school’s best pitcher and Peter Graves was his catcher. The Times reported that this “able Indian battery” does “fine work.”3 Jacob White Eyes was an Oglala Sioux born in the Dakota Territory in December 1869.4 In Lakota, his native language, he was Ištá Ská, meaning “white eyes.” As a young man, he stood more than 6 feet tall.5 Peter Sha-ga-na-she Graves was a Chippewa born in Minnesota in May 1870.6

On April 6, 1889, facing a team from the Pennsylvania Deaf and Dumb Institute, White Eyes struck out 21 batters and walked only one in a 9-2 victory.7 On June 5, against a semipro team from Norristown, Pennsylvania, he pitched well in a 4-2 loss.8 He was outdueled that day by Norristown ace John “Sadie” McMahon. Soon after, White Eyes and Graves joined the Foote Base Ball team of Philadelphia, managed by Harry F. Foote.9

The Middle States League was an integrated minor league that included two African-American teams, the Cuban Giants and the Gorhams. Foote’s team joined the league in July 1889 and represented Hazleton, Pennsylvania, 100 miles northwest of Philadelphia. The Hazleton Sentinel heralded the team’s arrival. “White Eyes and Graves are Indians, and are considered to be one of the best batteries in the State,” said the Sentinel.10 At this time, few Native Americans played professional baseball. Louis Sockalexis, believed to be the first Native American to play in the major leagues,11 debuted in 1897. Chief Bender, who lived at the Educational Home in the 1890s, made his major-league debut in 1903. Jim Thorpe came along a decade later.

On July 16, 1889, the Hazleton team lost its first game, 8-6, to the Cuban Giants.12 White Eyes and Graves were the battery in that game and in six of Hazleton’s next nine games. In those six contests, White Eyes’ earned-run average was a sparkling 0.88.13 But he won only three of the six because the Hazleton defense was woeful, committing 38 errors in the three losses. He and Graves play “splendid ball,” said the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It is very discouraging to see how badly they are supported.”14 In his first two weeks in the league, White Eyes pitched 59 innings, an arduous workload.

With a 4-6 record, the Hazleton team traveled to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, for a game on July 30. The Harrisburg Ponies, managed by James Farrington, had won 12 of their last 13 games, and with a 39-15 record were battling the Cuban Giants for first place.15 This was a tough test for the Hazleton squad. Foote chose White Eyes and Graves as his battery; Farrington went with Bobby Gamble and Kid Williams. Gamble had been invincible, allowing only five hits in 27 innings, July 17-24.16 He was masterfully assisted by Williams, “the finest catcher in the league.”17

About 300 fans attended the game on a rainy Tuesday. The league umpire did not show up, so Ponies utilityman Harry Koons filled in.

The home team batted first. White Eyes struck out the leadoff man, Bill Eagan, and walked Tommy Pollard, the Harrisburg captain. Pollard attempted to steal second base; Graves threw the ball over the head of second baseman Frank Rinn, and Pollard scampered to third. But Rinn grabbed George Hoverter’s hot grounder and threw home in time to get Pollard. White Eyes fanned Jerry McCormick for the third out.

Graves led off the bottom of the first and got aboard when Gamble misplayed his grounder. Graves reached second base on the play or by stealing second. Frank Conway struck out, but the third strike got away from Williams. Graves tried to score from second but was tagged out at the plate by Gamble.

White Eyes “threw the ball with terrific force”18 but was wild. The Sentinel reported that the Harrisburg batters were afraid of him. In the top of the second, he struck out Joe Jones and walked John Deasley and Howard Vallee. Williams advanced the runners with a sacrifice, but White Eyes escaped the jam by striking out Gamble.

In the bottom of the second, Gamble retired the Hazleton batters in order, fanning two of them. White Eyes did the same to the Harrisburg hitters in the top of the third. It was a pitchers’ duel.

Andy Knox led off the bottom of the third with a bunt down the third-base line. Gamble fielded it and threw wildly to first, allowing Knox to reach second. White Eyes struck out, but Williams missed the third strike. The play-by-play account omits the details, but Knox was put out and White Eyes reached second base. After Graves flied out to Jones in left field, White Eyes was called out for running out of the baseline on his way to third. Manager Foote felt the umpire’s incorrect calls in this inning deprived his team of two runs.

The Ponies broke the scoreless tie in the top of the fourth. After McCormick struck out, Jones reached on an error and Deasley drew a walk. Jones scored on a fielder’s choice, and Deasley tallied on a single by Williams. In the bottom of the fourth, Charlie Kelly drew a walk but was stranded.

Rain came down hard in the fifth inning. White Eyes retired the Ponies in order in the top half. With one out in the bottom half, Walter Plock drew a walk but Williams caught him napping at first. Gamble struck out Knox to end the inning.

The game was called due to the rain. The final score was Harrisburg 2, Hazleton 0. Gamble completed a five-inning no-hitter. White Eyes gave up only one hit in the loss. Each pitcher struck out seven batters.

The Harrisburg Call praised White Eyes and Graves: “A stronger battery and one that works together better cannot be found. Both are perfect gentlemen. … Their behavior while on the ball field and elsewhere is of such a character as will put many of their pale-faced brethren to shame.”19

Epilogue

Jacob White Eyes continued to pitch for the Hazleton team, but his effectiveness diminished. Perhaps he had a sore arm. In late August he was released “for poor playing.”20 Peter Graves remained with the team, which finished the season with a 10-27 record.

No record has been found of White Eyes or Graves playing for any other minor-league team. In 1892 they played together on a YMCA team in Philadelphia.21 Without Graves, White Eyes played for Guy Green’s barnstorming Nebraska Indians, 1898-1903.22

When not traveling, White Eyes resided in Kyle, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation of the Oglala Sioux. He married a Frenchwoman and learned enough of the French language that Buffalo Bill Cody brought him along on the 1905-06 European tour of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. White Eyes served as Cody’s French interpreter and performed in the show as one of the Indians.23 An associate of Cody later said of White Eyes: “He is quite an athlete. When we were in Paris, a team of the Buffalo Bill show played a game of baseball with the American students of Paris and Jake pitched. We won all three games.”24 White Eyes died on the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1937 at the age of 67.

Graves resided on the Red Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota. In the words of Erwin F. Mittelholtz, his biographer, Graves “was perhaps one of the greatest leaders and spokesmen that the Chippewas of the Red Lake Indian Reservation will ever know or remember. He ruled firmly, sometimes with an iron hand, yet he was a statesman and guardian for the rights and protection of the Red Lake Chippewa Indians for more than half a century.”25 Graves died on the Red Lake Reservation in 1957 at the age of 86.

Sources

Game account in “The Great Game,” Hazleton (Pennsylvania) Sentinel, July 31, 1889: 4.

Ancestry.com and Baseball-reference.com, accessed December 2020.

Mittelholtz, Erwin F. Historical Review of the Red Lake Indian Reservation, Redlake, Minnesota: A History of Its People and Progress (Bemidji, Minnesota: General Council of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians and the Beltrami County Historical Society, 1957).

Photo credits

Left image: Drawing of the Educational Home for Boys, from the cover of the Third Annual Report of the Educational Home for Boys (Philadelphia: Henry B. Ashmead, 1875).

Center image: 1887-88 photo of Jacob White Eyes as an 18-year-old student of the Educational Home for Boys, by John N. Choate, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Right image: 1905-06 studio portrait of Jacob White Eyes as a 36-year-old performer in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.

Notes

1 “The Lincoln Institution,” Philadelphia Times, January 22, 1886: 4.

2 “Chat,” Philadelphia Times, April 15, 1888: 12.

3 “About the Amateurs,” Philadelphia Times, May 27, 1888: 7.

4 1900 US Census.

5 “The Nebraska Indians,” Lead (South Dakota) Call, March 27, 1900: 3.

6 1900 US Census; Mittelholtz, 114.

7 “The Indians Win Their First,” Philadelphia Times, April 7, 1889: 3.

8 “The Indians Beaten at Norristown,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1889: 6.

9 “Base Ball,” Hazleton (Pennsylvania) Sentinel, July 8, 1889: 4.

10 “The Team Is Here,” Hazleton Sentinel, July 11, 1889: 4.

11 Baseball-almanac.com/legendary/american_indian_baseball_players.shtml.

12 “Base Ball,” Hazleton Sentinel, July 17, 1889: 4.

13 Computed from box scores in the Hazleton Sentinel, July 18-29, 1889.

14 “Gorham, 11; Hazleton, 9,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 25, 1889: 6.

15 “Base Ball,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Independent, July 30, 1889: 1.

16 “Another Game Won,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, July 18, 1889: 1; “Middle States League,” York (Pennsylvania) Gazette, July 23, 1889: 1; “The Middle States League,” Philadelphia Times, July 25, 1889: 2.

17 “1 to 0,” Harrisburg Independent, July 24, 1889: 1.

18 “White Eyes Surprised,” Harrisburg Telegraph, July 31, 1889: 1.

19 As reported in the Hazleton Sentinel, August 6, 1889: 4.

20 “Base Ball,” Freeland (Pennsylvania) Tribune, August 29, 1889: 1.

21 “Base Ball Notes,” Camden (New Jersey) Courier, April 22, 1892: 1.

22 “Baseball,” Crete (Nebraska) Herald, June 10, 1898: 1; “Normal School Happenings,” Grant County Witness (Platteville, Wisconsin), June 7, 1899: 5; “The Nebraska Indians,” Lead Call, March 27, 1900: 3; “Exeter Defeats the Indians,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), May 1, 1901: 2; “Indians to Play at Vincennes, Ind.,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 17, 1902: 7; “Told by an Indian,” Nebraska State Journal, December 7, 1903: 6.

23 “Wh-o-o-op! Iron Tail and His Braves Come,” New York Times, February 8, 1906: 9.

24 “Old Partners Now Mayors,” Omaha Bee, December 27, 1907: 2.

25 Mittelholtz, 110.

Additional Stats

Harrisburg Ponies 2

Hazleton 0

5 innings

Base Ball Grounds

Harrisburg, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.