Jefferson Street Grounds (Philadelphia)

This article was written by Jerrold Casway

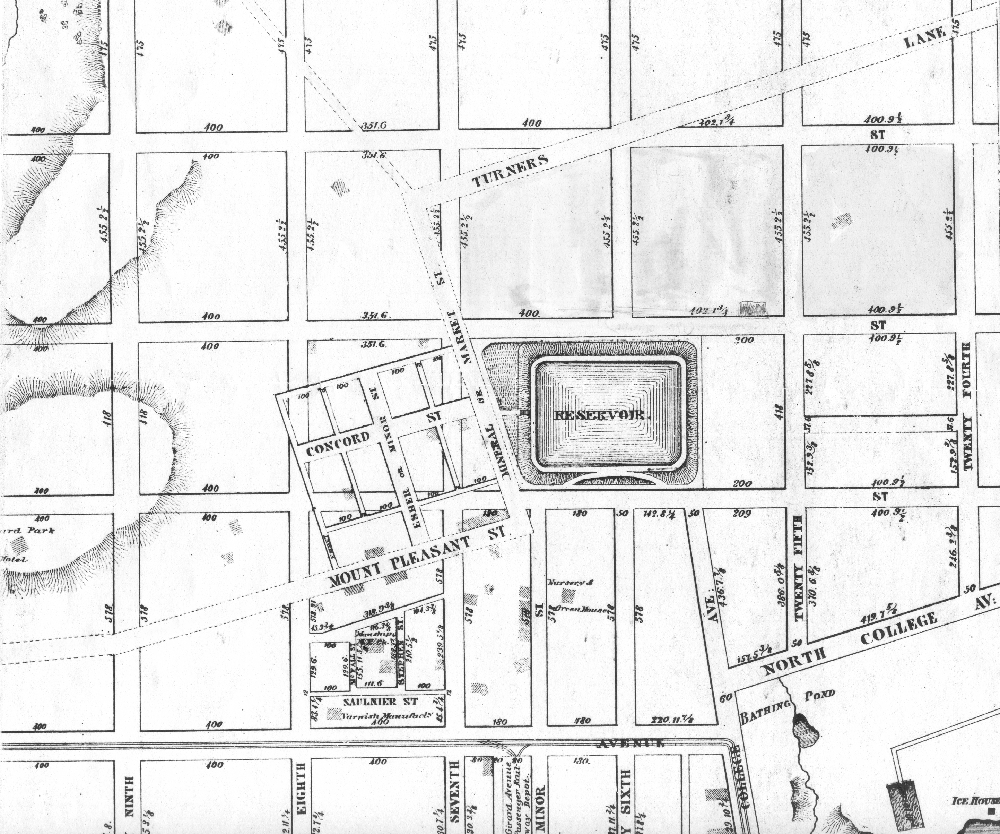

The Jefferson Street Neighborhood in 1860. From 24th Street to where Turner’s Lane ends is the ballpark site.

The Philadelphia ballparks situated at Jefferson and Master Streets, between 27th and 25th Streets, have a significant historic importance for our national pastime. Originally, this plot of land was known as the Jefferson Parade Grounds. It was used as a bivouac and training site in the years leading up to the Civil War.1

In the antebellum era, the major Philadelphia teams – the Athletics, Olympics, Mercantiles, and Keystones – found it difficult to secure suitable playing grounds in the city. Because of the community’s opposition to recreational sports, Philadelphia ball clubs were forced to play in Camden, New Jersey or across the Schuylkill River above the Fairmount Avenue Bridge near Harding’s Inn and Tavern. With baseball’s growing popularity, playing grounds soon encroached the outskirts of the city at 32nd and Hamilton and 11th and Wharton. It was not until the early war years that playing fields appeared at more accessible sites such as 10th and Camac Lane and 18th and Master Street. Eventually residential pressures compelled the Olympic and Mercantile ball clubs in 1864 to lease from the city “a handsome piece of ground at the north side of the Spring Garden Market” at 25th and Jefferson.2

Each club had two days a week for their practice. For a cost of about $1,500, the Olympics immediately built a clubhouse along Master Street and made substantial improvements by leveling and re-sodding the playing surface. The first game was played on Wednesday, May 24, 1864, between picked nines from Pennsylvania and New Jersey for the benefit of the United States Sanitary Commission. Without an enclosing fence, 2,000 spectators, paying 25 cents for admission, established the field’s boundaries. The only field-sitting was for ladies who sat behind the players’ bench.3 This ballpark was marked by certain features. Along the third-base/Master Street side was the grass embankment of the old Spring Garden Reservoir. Trees also disrupted the playing site, and until the grounds were enclosed, neighborhood animals wandered onto the field of play. Parking for horse carriages was in the left field foul territory, and no elevated reporters’ seating box existed until 1871.4 Visible behind the 27th and Master home plate intersection on the Girard College campus was the towering Greek-styled Founders Hall with its Corinthian columns.5

The Jefferson Grounds experienced a significant overhaul when the city’s best team, the Athletics, relocated there for the inaugural 1871 National Association of Professional Base Ball Players season. The Athletics had previously prospered at a popular site at 17th Street between Columbia and Montgomery Avenues before a housing development forced them to move to the Jefferson Grounds. Almost immediately, the Athletics tore down the old wooden grandstand and the encircling fence that had been erected in 1866. The new tenants re-sodded and leveled the playing surface, erected a 10-foot vertical slatted fence, and built a pair of tiered pavilions that abutted near the original home plate area on the corner of 25th and Master. Bleacher benches extended along the outfield lines. This rebuilt ball field held over 5,000 fans. This figure doubled during major ball games, when spectators lined up in front of the outfield fences and stood on wooden boxes that supported unstable raised wood planks. Those attendees who could not gain admission purchased 25-cent roof-top seats on neighboring houses, or sat on the branches of overhanging trees. These fans were termed “tree frogs,” and were likened to “living fruit.”6

Initially, the ball park was popular with women, but they eventually were turned off by the cursing, drinking, and the tobacco juice splashes on their dresses. Management tried to curb this rowdy behavior and attempted to attract fans with a music bandstand.7 There was even talk in the off-season about having football games at Jefferson Grounds.8 For the 1872 season, the champion Athletics resurfaced the infield, particularly the irregularly graded shortstop area. If these modifications were not completed in time for the new season the Athletics intended to schedule early-season games across the Delaware River in Gloucester, New Jersey.9

During the Athletics’ third season at the Jefferson Grounds, alarms were raised over the possibility that the site would be sold to housing developers. The Athletics’ directors were upset because they claimed to have invested over $7,000 on the ball field. After much debate and lobbying the politicians relented and the sale did not go through.10 A subsequent concern was the building of additional cheap seats in the outfield. In 1874 this need intensified when the grounds welcomed a new tenant, the Philadelphia Centennials (also known as the Quakers or Fillies). The new club had the field every Monday and Thursday. The Athletics took the site on Wednesdays and Saturdays.11 Prints of the playing grounds from a home plate perspective portrayed a wooden porch-styled construction.12

Near the 24th and Masters intersection, circa 1865–1866. Behind the clubhouse is the reservoir.

In spite of the clubs’ successes the ball park was losing money. The tenant teams compensated by raising ticket prices and erecting a new interior fence that could be plastered with paying advertisements. But the prevalence of gambling and drinking at the ball field kept people away.13 Eventually, the expenses of park maintenance and renovation exceeded revenues. They could not even afford a tarpaulin to cover the infield.14 It was hoped that the Athletics’ affiliation with the new National League in 1876 might save the old ball field. But the well-worn Jefferson Park did not appeal to fans and with low income and poor attendance the Athletics could not afford to remain in the new League. The unaffiliated and homeless Centennials now shifted their games to 24th Street and Ridge Avenue, Recreation Park, and the expelled Athletics’ rump team in 1877 played unsanctioned games wherever they could find a ball field. It was obvious that more revenue could be made by turning part of the Jefferson Grounds over to residential developers. It took the creation of the American Association in 1882 to revive the Athletics and the old Jefferson Park ball field.

The Athletics initially played their inaugural Association season at Oakdale Park at 11th and Cumberland. This leisure recreation site had a large lake and an adjoining playing field, used early on for cricket. Some distance from the Jefferson/Columbia ball-playing corridor, the Oakdale grounds had been in use since 1866.15 After nearly a decade the ball field became downtrodden until the displaced Olympics revived the grounds [1877-1881]. It was thus an ideal place for the revitalized Athletics to re-establish themselves.

Once the contracts had been signed, the Athletics razed the “old and unsightly” existing structure and replaced it with an upgraded wooden grandstand that held 2,000 spectators. The grounds were re-sodded and enlarged and open outfield benches were re-built for another 2,000 fans. A new fence was also erected for the start of the 1882 season.16 Despite these renovations the ball field could not accommodate the large crowds that embraced the new Athletics. As a result, the Athletics decided to relocate back to the Jefferson Street ball field. Unfortunately, the original two-block 25th Street square site no longer existed. The city had committed the eastern portion to a new high school and 26th Street was cut through the original ball grounds. But the Athletics, recognizing the transportation convenience of the site, negotiated an initial lease for $1,000 for the remaining 27th Street remnant. As a result, the former center-field space became the new home plate area for the Association’s Jefferson Street ball field.17

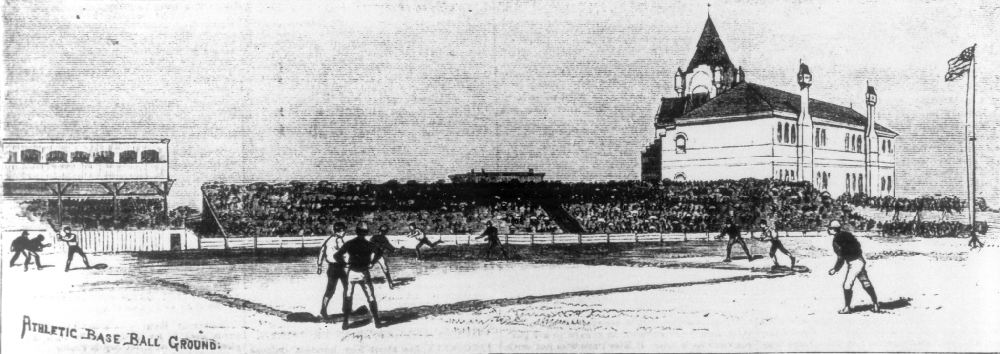

On the corner of 27th and Jefferson, the Athletics constructed “the handsomest ball grounds in the country.”18 The corner was backed up by a semi-circular two-tiered grandstand. Painted white and adorned in “ornamental … fancy cornice work,” the pavilions’ occupants enjoyed arm-chair seating behind a wire-mesh screen. The structure eventually was topped by 32 private season boxes, each holding five people, and a 22-person press box. The grandstand sat 2,200 people and open benches bordering the outfield held more than 3000 fans.19

After a successful 1883 championship season, the ballpark’s capacity was increased to 15,000. Special features abounded. The Oakdale flagstaff was planted at the 27th and Master Street corner20, a private external staircase for box ticket holders was erected, a ladies room, with a female attendant, was set up and a bandstand, linking the third-base pavilion and outfield seats, was erected. The outfield benches were fronted by a horizontal slatted barrier and the left-field fence held a scoreboard and advertisements. Towering over the left-field benches was the Jefferson Street Mission Church. In the distance, beyond center field, was the still-visible Founders Hall on the Girard College campus.21

The new Athletics and their renovated ball field were overseen by a popular local triumvirate, Charles “Pop” Mason, Lew Simmons, and Billy Sharsig. They raised funds to finance the franchise and redesigned the grounds to suit their needs and limited budget. Each served a term as team manager, but Sharsig managed the ball club for five out of the eight years at Jefferson Street. The Athletics’ record for these years was 519-464 for a .528 percentage. For most of their tenure at Jefferson Street the team was competitive and held their own attendance-wise against the National League Phillies. Their popularity was due to ballplayers like Bobby Mathews, Henry Larkin, Harry Stovey, and Louis Bierbauer. But Mason and Simmons recognized that the financial well-being of the franchise would be enhanced by Sunday ball playing. Unfortunately, Pennsylvania “Blue laws” forbade games on the Christian Sabbath. To counter this restriction Mason and his partners revived an old practice of scheduling games in Gloucester, New Jersey. Fans would assemble early on a Sunday morning at the South Street ferry and take a 45-minute crossing to Gloucester. Games were contested at a site next to the centrally-located race track that was served by horse trolleys. Radiating from this sporting juncture were saloons, betting parlors, fishcake stands, and other hostelries. One editorial called Gloucester “a nineteenth-century Sodom.”22

1883 ballgame at the new 27th and Jefferson Street field, looking north towards Jefferson street. Home plate is at 27th Street. The big building on the right is the Mission Church at 26th and Jefferson.

The Athletics began the 1886 season with an advertisement claiming to be the “oldest playing organization in the United States.” They asserted how they gave the Jefferson Street patrons “honest ball playing” when they posted the opening season schedule of games. These contests began at 4:00 P.M. and admission remained at 25 cents. Even the train schedule from Broad Street was publicized.23 Despite this confidence, the ball field was again threatened by city officials. These ambitious politicians were deterred when they were reminded that no one except the Athletics was willing to pay the $2,000 lease for the grounds.24 Once this issue was settled the Athletics re-dedicated their resources to repairing the grounds. They raised the infield, put in new cinder paths and purchased “an immense canvas to cover the entire infield.”25 Two years later, Mason and Simmons, looking for revenue, changed the ticket prices. General admission became 50 cents, and for an extra quarter women and their escorts could sit on cushioned seats in parts of the grandstand.26 This new revenue was intended to cover the expenses of erecting a new fence, replacing old floorboards and re-painting the pavilions.27 In spite of these changes, the growing threat of a players’ strike put the Athletics and their ball park in jeopardy.

In 1890, the players’ Brotherhood union brought a player strike team to Philadelphia. This anticipated rivalry moved the Pennsylvania Railroad to offer the Athletics a new ball field at a more competitive location with easy access from the Broad Street Station. It was rumored that the club was offered a five-year free lease if they moved to a site in West Philadelphia on the other side of the river below the Fortieth Street Bridge.28 Rather than lose or alienate their existing fan base, the Athletics turned down this speculative offer. Instead the Athletics, in grounds which had been updated in a number of seasons, prepared for the 1890 strike season, competing against two Philadelphia ball clubs in different leagues. The season, as expected, was a hardship for the American Association Athletics. Attendance waned and expenses mounted. By the end of the year the Athletics had new management and the Jefferson Street grounds were on the verge of being eclipsed.

By the middle of the strike season the Athletics were plagued by pre-existing financial woes. In 1888, this condition moved Mason, Simmons, and Sharsig to seek new investors, like H.C. Pennypacker and his partner William Whitaker. But during the strike season of 1890 the club’s problems mounted. In one instance, a suit for almost $300 was brought against the franchise in the Court of Common Pleas by carpenters who were not fully paid for their work on the pavilions.29 The ball club also owed $1200 in back rent and $1435 for lumber purchases. To pay these outstanding debts the grandstand, inside fence, seats, flagstaff, ticket boxes and office furniture , appraised at $765 were sold at the end of the season for $600.30 Sometime during these dealings, the Wagner brothers, J. Earle and George, wholesale meat distributers, took over the defunct franchise. Previously, the Wagners were stockholders in the city’s Player League team. After the Jefferson Street field’s sheriff sale, the Wagners shifted players from the three city ball clubs and set up their reconvene team at the Players League ball field, Forepaugh Park and Broad and Dauphin Streets.

Contemporary picture of the playground and softball field at the corner of 27th and Jefferson.

The Athletics played one more season in Philadelphia before merging with the new National League Washington ballclub that previously played in the American Association. It was a better end than what was in store for the Jefferson ball field. Vacant and partially denuded during the 1891 season, the ballpark was set ablaze by neighborhood youngsters in November. A good deal of lumber, stored for carpenters repairing the surviving outside fence, fed the flames.31 A month latter the Wagners’ offices on Vine Street burned down. Fortunately, the office safe, with the club’s records, tickets, and contracts, survived the fire.32 By the following summer the old Jefferson Street grounds, behind a new “substantial fence” were converted into an enclosed “pleasure park” and playground.33

By the mid-1890s there was speculation that a new baseball association would take over the Jefferson Street site.34 The future owners of the American League Athletics, Ben Shibe and Connie Mack, pondered the advantages of revisiting the old 27th Street ball field.35 They investigated the options of a new annual lease, but investors did not want to commit $30,000, necessary for preparing the ball park, to a short-term lease. Nor were neighboring residents and the new 25th Street School happy with the prospect of a new ball park and its anticipated crowds.36 As a result, the inaugural American League Athletics located to 29th and Columbia while the Jefferson Street site hosted leisure activities and an occasional Buffalo Bill Wild West Show.37

Today a memorial plaque to Billy Sharsig is mounted at the 26th Street recreation center and kids play on a softball field set on the grass and dirt of one of Philadelphia’s oldest and most important ball playing sites.

DR. JERROLD CASWAY is the Dean of Social Sciences at Howard Community College in Columbia, Maryland. He is the author of “Ed Delahanty in the Emerald Age of Baseball” and has completed, “The ‘Olde’ Ball Game: The Culture and Ethnicity of Nineteenth-Century Baseball.” He has written many articles on the early game and has frequently spoken at the Hall of Fame’s Nineteenth-Century Symposiums. He at work on a history of baseball in Philadelphia from 1832 to the building of Shibe Park.

Notes

1 Sunday Dispatch, March 27, 1859.

2 Sunday Mercury, May 16, 1866 and March 3, 1872.

3 Sunday Mercury, May 22, 1864; Philadelphia Inquirer, May 25, 1864. Olympics club house, c. 1866. Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Olympics Folder: B 13.55.

4 Evening City Item, May 15, 1871.

5 Painting by A. Kollner, 1865 in Logan Library, Philadelphia. See also T. Eakins painting, 1875, “Baseball Players,” at Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island.

6 Sunday Dispatch, September 15, 1872 and June 11, 1871; Philadelphia Inquirer, April 11, 1871.

7 Sunday Dispatch, April 7, 1873.

8 Sunday Dispatch, November 21, 1871.

9 Sunday Dispatch, April 7, 1872 and April 28, 1872.

10 All Day City Item, May 23, 1873.

11 Sunday Dispatch, January 25, 1874.

12 The Daily Graphic, April 30, 1873 and April 18, 1874.

13 All Day City Item, February 10, 1875; February 28, 1875; May 3, 1875.

14 All Day City Item, July 30, 1875.

15 Sunday Mercury, November 4, 1866.

16 Sunday Item, March 26, 1882.

17 By the end of the first year the Committee on City Property gave the Athletics a three-year renewable lease at $2000 a year. This agreement stood unless the new high school was built. In that case the city had to give the ball club a three-month notice of the forfeiture. Sunday Dispatch, December 9, 1883; Philadelphia Press, January 17, 1883; Sunday Dispatch, February 4, 1883,

18 Sunday Item, April 8, 1883 and April 1, 1883.

19 Sunday Item, April 8, 1883; Sunday Dispatch, January 14, 1883; Philadelphia Record, April 1, 1883.

20 Philadelphia Record, March 29, 1883.

21 Frank Leslie Illustrated Newspaper, October 6, 1883 and Gilbert & Bacon picture, 1884, Baseball Hall of Fame, B. 164.65. See also Philadelphia Record, March 29, 1883 and March 31, 1883. The late Larry Zuckerman calculated that the ball park’s dimensions were 288-440-352. Zuckerman to J. Casway, August 7, 1999.

22 North American, August 28, 1899; May 5, 1893; Philadelphia Inquirer, October 10, 1898.

23 Sporting Life, March 31, 1886.

24 Sporting Life, May 5, 1886.

25 Sporting Life, November 17, 1886.

26 Sporting Life, April 25, 1888.

27 Sporting Life, February 20, 1889.

28 Sporting Life, October 16, 1889; The Sporting News, October 19, 1889,

29 North American, June 26, 1890; Sporting Life, June 28, 1890.

30 North American, October 18, 1890; The Sporting News, October 18, 1890; Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 15, 1890.

31 Sporting Life, November 28, 1891.

32 Sporting Life, December 12, 1891.

33 Sporting Life, June 18, 1892; Sunday Item, June 19, 1892; The Sporting News, October 27, 1894.

34 Sporting Life, October 27, 1894.

35 The Sporting News, September 23, 1900 and November 24, 1900.

36 Philadelphia Press, December 20, 1900.

37 Philadelphia Press, May 13, 1901; Sunday Item, May 11, 1902.