Johnny Berardino

“Berardino is one of those intense fellows who believe the greatest shame in the world is not doing your best every time. He hustles until the last out of every game, and he doesn’t sit around crying about his hard luck.” — Bill Veeck, 1948.1

“Berardino is one of those intense fellows who believe the greatest shame in the world is not doing your best every time. He hustles until the last out of every game, and he doesn’t sit around crying about his hard luck.” — Bill Veeck, 1948.1

Known to generations of television viewers as Dr. Steve Hardy on General Hospital (1963-1996), John Beradino, actor, had, during his early adult life, been Johnny Berardino, baseball player. And his first acting roles came before television was invented.

John Berardino was born in Los Angeles on May 1, 1917. He was the third child born to Ignazio and Anna Musacco Berardino, both natives of Canneto, Rieti, Lazio, Italy, a town on the Adriatic Sea. Ignazio came to the United States in 1905. His mother immigrated in 1911. Ignazio was the foreman at a wholesale meat-packing company. John’s older brother, Joseph, was born in 1914 and his sister, Mary, in 1916. His father died in 1965, and his mother died at 100, on April 5, 1989.

Berardino’s movie career predated his first trip to the Los Angeles playgrounds to play baseball. At the age of 6, he appeared as an extra in three early Hal Roach “Our Gang” films, before sound came to film. His pay amounted to “box lunches that they handed out on the set.” His mother felt he would be the next great child star and persuaded his dad to invest $10,000 in a movie starring the 10-year-old child. But the film was never finished.2 “My dad gave me a bat and said, “Go make like “Push-em-up Tony,” (Tony Lazzeri, like Berardino, an Italian from California, was his hero).’”3 Young Johnny was off to the local playgrounds with a ball and bat. He attended Castelar Grade School and went on to Belmont High School, where he starred in football as well as baseball.

Berardino entered the University of Southern California in the fall of 1935, and served on the Sophomore Class Council during the 1936-37 school year. He was a member of Phi Kappa Tau fraternity. Fred Mosebach of the San Antonio Express, who spoke with Berardino during his minor-league days, wrote that Johnny’s ambition was to become a sportswriter, but the youngster would find his career elsewhere. 4 He had also, during his time at USC, done some acting, but when asked about his acting during a 1939 interview, he was calm and modest, saying, “Just tell ’em I was a tree in the forest scene.”5 By then, his focus was on baseball.

In the spring of his sophomore year, Berardino made the varsity baseball squad as a second baseman, but when he suffered a broken finger fielding a ball, his coach temporarily switched him to the outfield to get him playing time without undue hazard to his finger. Despite the injury, Berardino led the Pacific Coast Collegiate League with a .424 batting average. He was scouted by Willie Butler and signed after that season by Jack Fournier of the St. Louis Browns, a signing protested by USC coach Justin M. “Sam” Barry.6 The Browns sent Berardino to the Johnstown (Pennsylvania) Johnnies of the Class-C Middle Atlantic League. He so impressed the organization that Browns business manager Bill Dewitt said, “He’s been hitting around .325, is exceptionally fast, has a strong arm, and is a good fielder. All our scouts agree that he’s a sure major-league prospect. He’ll probably serve with San Antonio next year.”7 At Johnstown Berardino batted .334 with 38 extra-base hits, 12 of which were home runs.

In spring training with the San Antonio Missions in 1938, Berardino went 5-for-5 with three homers on March 20 as the Missions defeated the Laredo Stars, 13-3.8 During the season he batted .309 as the Missions finished second in the Class-A1 Texas League. He had 41 doubles, two triples, 13 home runs, and 20 stolen bases. Before the season Browns scout Ray Cahill had said, “The lad can’t miss.”9

In May of that season Berardino showed an ability to play while in pain. He played through a game with an injured finger. With his finger taped up, he fielded eight balls at second base and was involved in three double plays. The next day it was determined that the finger was broken.10 When he was injured he was batting over .400. He missed 20 games, but still led the league in chances handled (810) and participated in a league-leading 107 double plays.

After excelling at San Antonio 1938, Berardino was praised by new Browns manager Fred Haney.11 In spring training at San Antonio, Berardino and Sig Gryska, who had set a record for converting double plays the prior season at Mission Field, were pairing up to take their act to the major-league level. Berardino was also showing off his basestealing skills, having stolen three bass in the early spring games.12 Berardino and Gryska got more playing time in the spring as the regular Browns tandem of Don Heffner and Red Kress were holding out.13 Heffner’s holdout continued into April and Berardino took full advantage, getting the nod to start on Opening Day.14

On Opening Day, April 22, 1939, Berardino hit seventh in the batting order and went 1-for-4 against the White Sox at Comiskey Park. In the fourth inning, with the Browns leading 2-1 and runners on second and third, Berardino got his first major-league hit, a single off future Hall of Famer Ted Lyons, driving in the two runners. He hit safely in his first nine major-league games. As April ended, he was batting .333. However, a May slump shot Berardino’s average down to .243. Nevertheless, his manager stuck with him and he was back on top in June, going 31-for-89 (.348) with eight extra-base hits, including his first big-league homer. The third-inning two-run blast on June 29 came off Thornton Lee and helped the Browns thump the White Sox, 9-3. However, Berardino’s efforts were on most days lost in another year of frustration for the Browns. The team finished the season with a 43-111 record, worst in the major leagues. Berardino had a late-season slump and finished his first season with a .256 batting average. He hit five homers and drove in 58 runs in 126 games.

Hopes were high in St. Louis as the 1940 season begun, as their turn to youth was producing some early positive results, not the least of which was Berardino. The optimism was premature. Three games into the season, the record was above .500 (2-1). It was downhill from there. St. Louis quickly fell to eighth place. But from June 4 through July 2, the Browns went 19-12 and were in fifth place, four games below .500. On June 5, Berardino went 4-for-7 and scored the winning run as the Browns defeated the Red Sox 4-3 in 14 innings at Fenway Park. Four days later, at Philadelphia, Berardino homered in each game of a doubleheader, as the Browns swept the pair. The team, however, would revert to its losing ways and lose 14 in a row in July. Berardino had a role in stopping that streak with a game-winning homer on July 19. The team would up with a sixth-place finish (67-87), an improvement over the prior season’s eighth-place result. Berardino improved on his 1939 numbers, raising his average to .258 with career highs in doubles (31) and homers (16). The Browns moved Berardino to shortstop during the season and the results were favorable. Dick Farrington remarked in The Sporting News that “some observers who have watched Berardino freely predict that he will be the best shortstop in the league in another year. He possesses what is known as ‘ball sense’ in tracking down grounders, has ample speed and a fine throwing arm.”15

In the offseason between 1940 and 1941 Berardino was back performing as an actor, working at the Pasadena Playhouse in a performance of A Slight Case of Murder. In 1941, despite some injuries, Berardino played some of his best ball so far. As late as June 5, he was batting above .300, and for the season he would post his best average of his career, .271. Although the Browns (70-84) finished sixth, there was hope that improvement was on the horizon. When Berardino’s name came up in trade rumors, the Browns were quick to stop such speculation. With only five home runs, he managed a career-high 89 RBIs, second best on the team.

And then things changed.

In January 1942, shortly after the United States entered World War II, Berardino enlisted in the US Army Air Corps and went off to Higley Field in Chandler, Arizona, for flight training. Unable to qualify as a flier he was given a discharge and rejoined the Browns. He appeared in 29 games with the team in 1942, but had no set position. He registered only 74 at-bats and had an average of .284. Shortly after the season, he joined the Navy,16 and was stationed at the Naval Air Station at Lambert Field, Missouri.17 He moved on to the Physical Instructors’ School at Bainbridge, Maryland, and then to the Naval Air Station in San Pedro, California, where he managed the facility’s baseball team.18 When the Browns won the 1944 pennant, Brown was stationed at Pearl Harbor. During his time there, he injured his back falling from a jeep.

Berardino returned from the Navy for the 1946 season and had a great start. At the time of the All-Star Game, he was batting over .300 and the Browns were miffed that he wasn’t selected for the All-Star team. He fashioned a career-high 21-game hitting streak from May 30 through June 20. By season’s end, his average had dropped to .265, but he had 39 extra-base hits and 68 RBIs. The Browns, after being as high as third place in early May, slipped back to their customary spot in the second division, finishing in seventh place, 38 games out of first. During the offseason, Berardino resumed acting, performing, and learning at the Pasadena Playhouse.

In 1947 with the Browns, Berardino got off to a terrible start at the plate, and on April 27 he had the dubious distinction of hitting into a triple play against the White Sox. He withstood persistent back pain from his Navy days, but was limited to 90 games by two serious injuries. The more severe injury was a broken arm on June 17 that caused him to miss 35 games. He sustained the injury when hit by a fastball thrown by Dave Ferriss of the Red Sox. At the time of his injury, he was batting only .180. After he returned, his hitting improved, but he was sent to the bench again on August 8 when he was hit on the hand by a pitch thrown by Cleveland’s Allen Gettel. He missed all but one of his team’s next 25 games, but returned to bat .362 in 24 September starts. For the season, he batted .261. His 22 doubles gave him more than 20 doubles in each of his first five full seasons in the major leagues. The Browns, however, were still the Browns, finishing again in last place.

After the 1947 season, the Browns sought to trade Berardino and worked out a trade with the Washington Senators for Jerry Priddy. Berardino saw no advantage in moving from an eighth-place team to a seventh-place team and announced his retirement to seek a full-time film career. His first role was as a horse trainer in the film The Winner’s Circle, featuring jockey Johnny Longden. In announcing his retirement, Berardino said, “I’m getting a seven-year contract from Polimer Studios and it’s a better deal than I could get in baseball. They like my future in the movies and so do I. Anyway, when they start moving you around like cattle without your consent, it’s time to quit baseball. I was never approached on the trade and knew nothing about it until I read it in the papers.”19

However, by the time the film was released on June 8, 1948, Berardino was back on the ball field, this time with a contender. After the deal between St. Louis and Washington fell through, Bill Veeck of the Cleveland Indians wanted to shore up his infield and to strike a pre-emptive blow against the Detroit Tigers, who were looking to acquire Berardino.20 On December 9, 1947, he paid a handsome sum ($65,000) to the Browns for the handsome ballplayer and quickly, at the insistence of Berardino’s film producer, insured John’s face in the event the player suffered a baseball-related injury. Reports differ on the amount of the coverage. Contemporary reports had it at $100,000,21 but more recent accounts showed the amount as $1 million.22 Berardino also had an attendance clause written into his contract. For each 100,000 the Indians drew at home over 2 million spectators, the player would receive $1,000. To owner Veeck, the contract was little more than a publicity gag as the team had never drawn more than 1.6 million, its all-time high having been 1,521,978 in 1947.

Originally, George Metkovich was sent from Cleveland to St. Louis as part of the trade, but the Browns returned Metkovich to Cleveland, when it was determined that he had a broken finger, with the Browns getting $15,000 on top of the initial $50,000 for Berardino. Veeck’s reasoning for the high price tag was, “He’ll be worth the price and then some if one of our regulars goes into a slump or is injured. The way the Red Sox have loaded up for next year’s pennant race, anyone who hopes to catch them will have to be as strong in reserves as on the front line.”23

With Cleveland, Berardino backed up Joe Gordon at second base. He was used sparingly, appearing in 66 games and batting only .190. However, the average is deceiving. He started games at each of the four infield positions and, in spots, Berardino shined. He played in 10 straight games, mostly at second base, from May 25 through June 4, when Gordon was injured. During this time, he batted .344, as the Indians won six of the games. On 18 occasions, including 14 starts between June 27 and July 25, Berardino platooned with Eddie Robinson at first base and played errorless ball.

When shortstop-manager Lou Boudreau was injured in early August, Berardino stepped in for six starts. On August 8 he contributed to both wins in a doubleheader sweep of New York. In the 8-6 first-game win, in front of 73,484 at Cleveland Stadium, he homered off Spec Shea during a five-run sixth inning. He walked and scored ahead of Eddie Robinson’s game-winning two-run homer in the eighth inning. In the nightcap, his seventh-inning sacrifice advanced the winning run to second base.

As September began, it was a three-team race in the American League for the pennant. The Athletics had fallen from contention. The Red Sox were in the lead, but the Yankees and Indians were in close pursuit. Unfortunately for Berardino, his bat went cold in the heat of the pennant race. From August 10 through September 18, he went 0-for-30 and saw his batting average plummet. As September turned into October, the Indians took the league lead and had a chance to clinch the pennant on the final day of the season. However, although Berardino broke his hitless streak with a pinch-hit single, the Indians lost to the Tigers and fell into a tie with the Red Sox. They defeated Boston in a one-game playoff to advance to the World Series, where they defeated the Boston Braves in six games. Berardino did not play in the World Series.

Berardino’s foresight in insisting on the attendance clause in his contract paid off. The Indians drew a record 2,620,627 fans in 1948, and Berardino got a $6,000 bonus. That attendance record stood until 1995.

Berardino was still with the Indians in 1949 and used the season to play with the Indians and do a movie, The Kid From Cleveland, along with his teammates. In the film, starring George Brent, Berardino played a gangster character called Mac. Russ Tamblyn played a troubled youth who was helped by the members of the team. The film’s premiere took place in Cleveland on September 2, 1949.24

Berardino spent his second season with the Tribe once again on the bench, getting into only 50 games. His .198 batting average once again did not show his value to the team. His voice was often heard from the bench by the opposing players and he became highly regarded as a bench jockey. Early Wynn told Berardino, “You got me so mad when I was with Washington (in 1948), that when you got on first base, I tried to throw the ball right at you.” Al Simmons added, “That guy (Berardino) is a dandy. He used to get our (Athletics) players so bothered they’d come back to the bench cussing. Oh, is he rough!”25

During his time with Cleveland, Berardino was noted for his Captain Bligh speech, in which he imitated Charles Laughton’s performance in Mutiny on the Bounty. In a reminiscence in 1998, teammate Bob Lemon said that Berardino was “one of the comrades on the team. He did it all,” Al Rosen added, “He was a thespian. He would jump on a table in the clubhouse and sprinkle water on everybody while giving his Captain Bligh speech.”26

In 1950, Berardino played in only four games with the Indians before being sent to their San Diego affiliate in the Pacific Coast League in May. In June, he was transferred to Sacramento in the same league, and on August 9, he was released by the Indians. He signed with the Pirates and was with them for the balance of 1950, playing in 40 games and batting .206.

After the season, the Pirates released Berardino and he signed with the Browns. A stellar performance during spring training earned him the nod at third base and he played in the first dozen games of 1951, batting .311. He played regularly through May, but his playing time diminished thereafter. His last game of the season was on July 4. When Bill Veeck took over the team on July 5, many players were shown the gate, and Berardino became a coach.27 He was relieved of his coaching duties after the season.

Berardino returned to Cleveland at the beginning of the 1952 season, but not before making a return to movies, appearing as ballplayer Bill Sherdel in The Winning Team, which starred Ronald Reagan as Grover Cleveland Alexander. Prompting the invite to spring training from Cleveland general manager Hank Greenberg was the anticipated loss of players to the military draft during the Korean War. Berardino was clearly underperforming in 35 games with the Indians, going only 3-for-32 before being traded to the Pirates on August 18. He finished his major-league career with the Pirates in September 1952. He went 8-for-56 with four doubles in 19 games with the Pirates, as the Bucs finished in the cellar with a 42-112 record, not much different from his first team, the 1939 Browns.

For his career, Berardino batted .249 with 167 doubles, 23 triples, and 36 home runs. He had 387 RBIs.

Berardino, who was an actor before, during, and after his baseball life, became a full-time actor after the 1952 season. He appeared in more than 25 movies, often in minor uncredited roles (including sitting at a bar in Marty and playing a police sergeant in North by Northwest), but his greatest success came in over 100 roles on the small screen. His early TV credits included I Led Three Lives, in which he appeared as Special Agent Steve Daniels. He appeared on Superman, in The Cisco Kid, and on The Lone Ranger, where he did four episodes (separate outlaw characters) in 1956.

Berardino turned to writing and co-authored scripts with Charissa Hughes for the television series Shotgun Slade, which aired from 1959 through 1961.

In 1960, Berardino returned to the big screen, appearing in Seven Thieves, which starred Edward G. Robinson and involved a caper that took Robinson and his comrades to a heist in Monte Carlo. This time Berardino was on the side of the law, playing a detective. The film received good reviews.

Still in detective garb, he joined the cast of The New Breed on television in 1961 as Sergeant Vince Cavelli, starring alongside Leslie Neilsen. The show was well received by critics but lasted only one season.

Berardino’s big break came in 1963 when he took on the role of Dr. Steve Hardy on television’s General Hospital. The program was the first foray into soap opera for ABC and John Beradino was with the show for 33 years, appearing for the final time one month before his death. In 1973, thinking that daytime performers were undervalued, he championed the cause of the Daytime Emmy Awards.28 The first awards were presented on May 28, 1974. Although he was nominated for an Emmy in each of the first three years, he was not selected for the award.

In 1981, Beradino appeared in the made-for-television movie, Don’t Look Back, the story of 1948 Cleveland Indians teammate Satchel Paige. In 1993, 45 years after receiving his World Series ring and 30 years after the debut of General Hospital, Berardino was awarded a place on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame.

John married 18-year-old Jeanette Nadine Barritt on November 23, 1941, and they had two children, daughters Antoinette, born in 1942, and Celeste Ruth, born in 1945. They were divorced in March 1955.29 Jeanette died in 1970. On January 20, 1961, he married actress Charissa Hughes, 17 years his junior, with whom he had collaborated as a writer. She died on June 14, 1963. He was married for the third time, to Marjorie Binder, on April 30, 1971. They had a daughter, Katherine (1973-2017), and a son, John Anthony (1974-). Berardino died from pancreatic cancer on May 19, 1996. Berardino’s brother, Joseph, had died in 2002 and his sister, Mary, in 2011.

Actress Rachel Ames, who played Berardino’s wife on General Hospital, talked lovingly of her co-star: “John was like a father confessor to everybody in the cast. He always had a cheery word and liked to tell funny stories. He was a great dancer and loved to ride horses. On breaks between acting, he would play catch.”

This biography originally appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

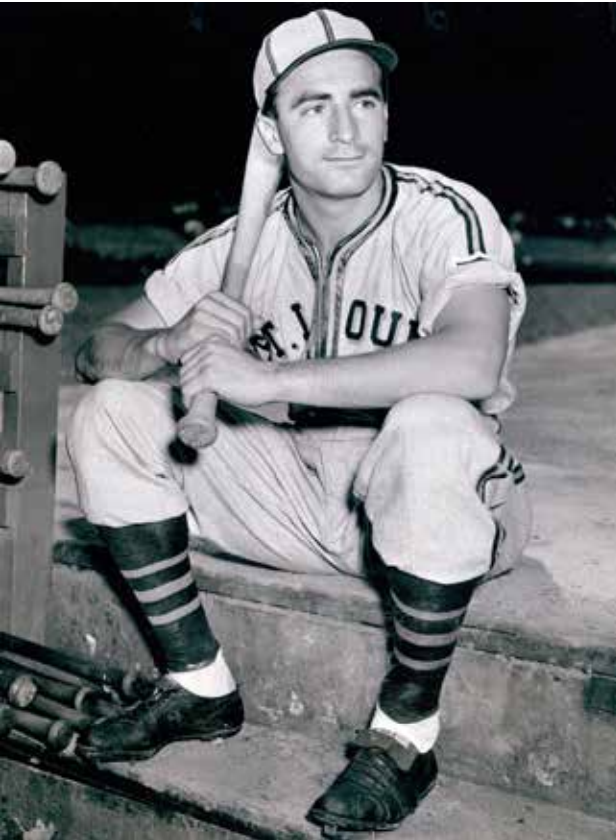

Photo Caption

Big leaguer John Berardino (on the ballfield) or Beradino (in movies and on TV) enjoyed a healthy big-and-small screen career; he is best-recalled as Dr. Steve Hardy on General Hospital.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, Ancestry.com, the Johnny Berardino player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following:

Drohan, John. “It’s Short Step From Field to Footlights,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1956: 13-14.

Grimes, William. “John Beradino, 79, An Enduring Soap Opera Star,” New York Times, May 22, 1996.

The following articles, although included in the notes, are singled out as being particularly helpful.

Dolgan, Bob. “Two Series Star: After Helping the Indians to the 1948 Title, Berardino Found Fame as Soap Opera Actor,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 23, 1998: 1-C.

Farrington, Dick. “Dark and Handsome Berardino Started in Films — at Six,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1939: 3.

Notes

1 Gordon Cobbledick, “Veeck Applies Psychology in Reshuffling Roommates,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1948: 4.

2 Eirik Knudsen, “Beradino, on ‘Hospital’ for 25 years, Operated in the Infield for ’48 Tribe,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 5, 1988: TV Week-2.

3 Jeanie Chung, “Player-Turned-Actor Is Just What Doctor Ordered,” Baseball Weekly, May 23, 1991.

4 Fred Mosebach, “John Berardino of San Antonio Missions,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1938: 10.

5 Dick Farrington, “Dark and Handsome Berardino Started in Films at Six: But with Eye on Lazzeri, Brown Rookie Landed on Diamond,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1939: 3.

6 “Browns Signing of Collegian Brings Kick From Coast Coach,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1937: 2.

7 Carl Felker, “Long Rookie String Lined Up by Browns,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1937: 2.

8 “Missions Win Over Laredo Stars,” Dallas Morning News, March 21, 1938: II-2.

9 “New Brownies Recruit: John Berardino,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1939: 1.

10 Ibid.

11 “Mixing Old With New to Paint Brown Picture in Brighter Hue,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1939: 1.

12 Brown Byrd, “Browns Taking on Rose-Colored Tint: Gryska, Berardino Develop into Nifty Keystone Combination,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1939: 12.

13 Farrington, “Brownies May Fit Kids Into Keystone,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1939: 2.

14 Byrd, “Berardino Scheduled to Open at Second Base for Brownies,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1939: 2.

15 Farrington, “Berardino Browns’ Tall Man at Short,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1940: 2.

16 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 29, 1942: 4B.

17 The Sporting News, June 3, 1943: 11.

18 “In the Service,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1944: 14.

19 Shirley Povich, “Swap for Berardino Turns Into Movie Shocker for Nats,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1947: 10.

20 Bill Veeck (with Ed Linn), Veeck as in Wreck (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 148.

21 Associated Press, “Berardino Gets Face Insured,” Sandusky (Ohio) Register, January 5, 1948: 5.

22 Veeck, 134.

23 Ed McAuley, “Movie Actor Berardino Gets Into Cleveland Picture,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1947: 11.

24 McAuley, “Indians’ Reel Roles Marked by Realism: New Film Is Well Received at Cleveland Premiere; Diamond Sequences Good; Veeck in Prominent Part,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1949: 19.

25 Hal Lebovitz, “Active-Sub Berardino Rates High as Jockey,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1950: 16.

26 Bob Dolgan, “Two Series Star: After Helping Indians to the 1948 Title, Berardino Found Fame as a Soap Opera Actor,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 23, 1998: 1C.

27 Ray Gillespie, “One Team Playing, One Coming, One Going,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1951: 4.

28 Jerry Buck, Associated Press, “Daytime Opera Performers Want to Compete for Awards,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 11, 1973: 22E.

29 Associated Press. “Berardino Is Sued for Divorce Third Time,” Sacramento (California) Bee, March 2, 1955: 28.

Full Name

John Berardino

Born

May 1, 1917 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

May 19, 1996 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.