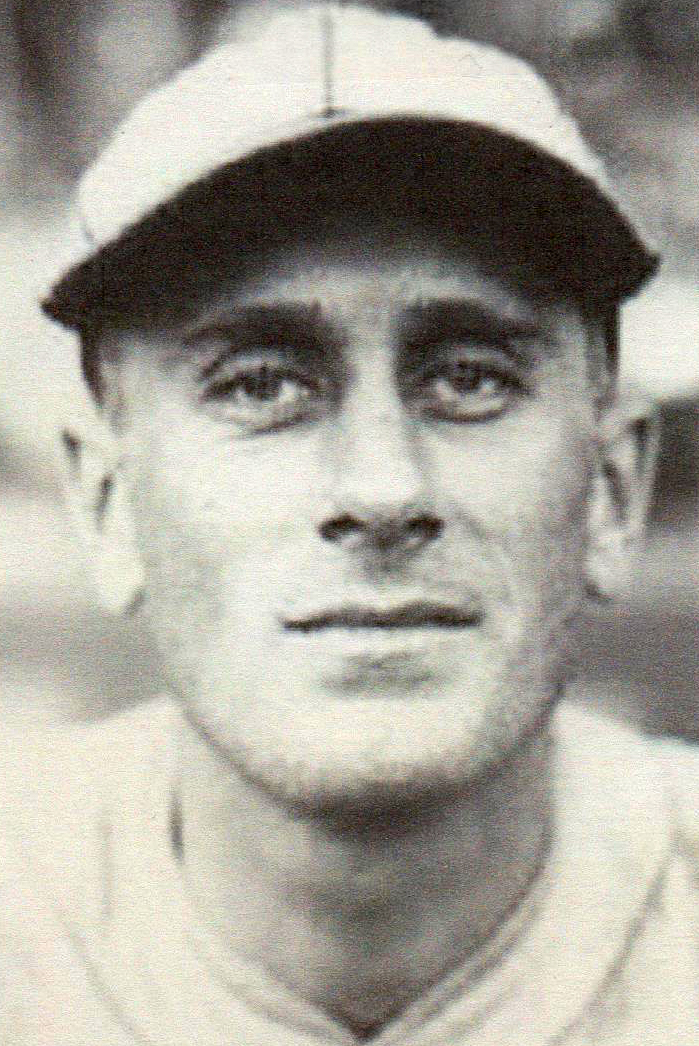

Ossie Orwoll

In 1927, left-handed pitcher-outfielder Ossie Orwoll led American Association hurlers in winning percentage (.739) and came in second for AA batting honors (.370). As a result, he became a high-priced purchase of Philadelphia Athletics co-owner/manager Connie Mack. His performance at the A’s camp the following spring was equally impressive, prompting comparison to former lefty pitcher turned star first baseman George Sisler. Others saw a line drive-hitting version of an even greater luminary: converted southpaw hurler turned record-breaking slugger Babe Ruth. As a rookie, Orwoll did not disappoint, providing the Athletics with useful service at both first base and on the mound. But the following season, things soured for the newcomer. By late August 1929, Orwoll’s tenure as a major leaguer was over, stymied by inability to pierce a talent-stuffed Philadelphia lineup, arm trouble, and the spleen of manager Mack.

In 1927, left-handed pitcher-outfielder Ossie Orwoll led American Association hurlers in winning percentage (.739) and came in second for AA batting honors (.370). As a result, he became a high-priced purchase of Philadelphia Athletics co-owner/manager Connie Mack. His performance at the A’s camp the following spring was equally impressive, prompting comparison to former lefty pitcher turned star first baseman George Sisler. Others saw a line drive-hitting version of an even greater luminary: converted southpaw hurler turned record-breaking slugger Babe Ruth. As a rookie, Orwoll did not disappoint, providing the Athletics with useful service at both first base and on the mound. But the following season, things soured for the newcomer. By late August 1929, Orwoll’s tenure as a major leaguer was over, stymied by inability to pierce a talent-stuffed Philadelphia lineup, arm trouble, and the spleen of manager Mack.

Unhappily for Orwoll, the Athletics did not release him outright. Instead, the club maintained an unexercised option on his services until his prospects for a second major league chance dimmed. Still, he continued playing ball, first for minor league clubs, thereafter for independent and semipro nines into the late 1940s. When he died some 20 years later, Orwoll no longer conjured comparisons to Cooperstown immortals like Sisler and Ruth. Rather, like once touted lefty pitcher/position player Jack Bentley, Ossie Orwoll was relegated to the forlorn category of “jack of all trades, master of none.”1 The story of this athletically gifted might-have-been follows.

Oswald Christian Orwoll was born on November 17, 1900, in Portland, Oregon. He was the second of six children2 born to the Reverend Sylvester Martinus Orwoll (1869-1925), a Lutheran minister, and his wife Anna (née Dahl, 1877-1963), the daughter of a Lutheran clergyman. Both parents were native Midwesterners of Norwegian descent. Shortly after Ossie’s arrival, Reverend Orwoll was appointed pastor of First Lutheran (later St. Olaf’s) Church in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. In due course, Ossie attended area schools through graduation from Toronto (South Dakota) High School in 1917. He also briefly attended Lutheran Normal School in Sioux Falls. Evidently misrepresenting his age, he then enlisted in the Army, becoming a member of a South Dakota field artillery brigade.3

The teenager spent World War I stationed stateside and was mustered out in February 1919. That spring, he took his first stab at a professional baseball career, signing with the Sioux Falls club in the unaffiliated South Dakota League, but was released before regular season play began.4 Orwoll then found a job at the International Harvester plant in Sioux Falls.5 A spring 1921 tryout with the Watertown (South Dakota) Cubs of the Class D Dakota League also came to naught. Orwoll’s athletic fortunes rebounded, however, once he pursued a family tradition: enrolling in Luther College, a small Lutheran Church-affiliated liberal arts school located in rural Decorah, Iowa, and a charter member of the Iowa Intercollegiate Athletic Conference. There, his prolific performance for the Luther Norsemen on the gridiron, hardwood, cinders, and diamond garnered regional press attention and, eventually, the interest of professional scouts.

Perhaps unconventionally, the path to athletic glory at Luther had been blazed a generation earlier by his father, a baseball and track standout during his undergraduate days as well as captain of the 1894 Luther football team.6 And just the previous year, the leader of Luther’s football, basketball, and baseball squads had been Ossie’s one-year-older brother Sylfest Orwoll, known as “Bilt.”7 Upon Ossie’s arrival, the Orwoll brothers became teammates.8 But Ossie’s exploits far exceeded those of his father and brother, earning him an extraordinary 14 varsity letters.9 He was a quick two-way halfback in the fall, a reliable back-courter in winter, and a 220-yard dash man and hurdler in the spring.10 But it was Ossie’s exceptional talent on the baseball field that drew the most acclaim.

Sturdily built but slender (5-foot-11 and 158 pounds),11 the lefty alternated between the pitcher’s mound and center field during his four years at Luther. Captained by brother Bilt, the 1923 Luther team went undefeated and began attracting regional notice.12 Ossie came fully into his own once Bilt graduated, succeeding his brother as baseball team captain. During the 1924 season, however, he interrupted his athletic commitments long enough to assume a new one as a husband. On May 10, Ossie married Edna Holm, a 21-year-old Decorah native. In time, the birth of daughter Barbara (1926) and son Oswald Dean (1930) would make the family complete. Meanwhile, Ossie continued playing ball, filling his summers with semipro engagements under the alias Lefty Dahl (his mother’s maiden name). And it was a Dahl mound performance that ultimately placed our subject on the path to a major league career.13 For the time being, however, Orwoll returned to Luther for his senior year, spurning contracts proffered by Philadelphia A’s boss Connie Mack and other big league clubs.14

After completing his normal regimen of football in the fall and basketball in the winter, Ossie turned in a stellar season on the collegiate diamond. He continued to punish small college pitching, ending his Luther career as a .442 hitter.15 Orwoll was similarly dominant on the mound, throwing two no-hitters in a single late-season week – but with mixed results. An untimely walk and teammate errors cost him a 2-0 loss to arch-rival St. Olaf on May 18, while he was a 7-0 victor over Upper Iowa six days later.16 But it was a standout Lefty Dahl performance against their club the previous summer that stuck with management of a crack semipro nine in Wisconsin.

Following the award of his bachelor’s degree from Luther in the spring of 1925, Orwoll accepted an offer to play with the La Crosse (Wisconsin) Nelsons, a play-for-pay club operated by a city clothing store.17 He was signed as a pitcher but inserted into the everyday lineup after a two-homer game against a Mason City (Iowa) team. Orwoll torched opposition pitching for a .410 batting average (with 43 extra-base hits) in 55 games played for the powerhouse (52-17-1, .752) Nelsons club.18 Among those paying close heed to his batting prowess was a figure prominent in in-state baseball circles: Otto Borchert, owner of the Milwaukee Brewers of the Class AA minor league American Association. In mid-September, Borchert induced Ossie to sign with his club for the remainder of the 1925 season. But the contract included an atypical provision that “entitled Orwoll to his unconditional release should he demand it” at season’s end.19 In nine games for the Brewers, Orwoll treated top-notch minor league pitching as roughly as he had college and semipro hurling, batting (16-for-37) .433 with six extra-base hits, 12 runs scored, and two stolen bases.20

Content with his placement in Milwaukee, Orwoll did not opt for free agency that fall and remained in the Brewers fold for 1926. He did double duty, taking a semi-regular turn on the mound while starting 40 games as an outfielder. But by so doing, he failed to develop his full potential as either a pitcher or a batsman/position player, a situation that would recur in future, as well. In 33 outings for the Brewers, Orwoll posted an Association-best 12-4 (.750) hurling log,21 but with a less-than-impressive 189 base hits allowed and a 4.07 ERA in 168 innings pitched. He also fell off at the plate, batting .287 with only 11 extra-base hits in 181 at bats. Still, the 93-71 record posted by Milwaukee represented a 19-win improvement over the previous season. The club was quick to reserve Orwoll for 1927.

Having been a standout running back and punter/drop-kicker at Luther – many locals considered football Orwoll’s best sport – Ossie then alarmed Brewer management by signing with the Milwaukee Badgers of the fledgling National Football League.22 But he saw only limited game action and the crisis passed when the Badgers disbanded after the season. Just before Christmas, Orwoll re-signed with the Brewers for the upcoming baseball season amid rumor that several major league clubs were seeking an option on him from club boss Borchert.23

For one season at least, Orwoll disproved the thesis that splitting time as a pitcher and position player retarded his development at either spot. He performed superbly in both roles. As a pitcher, he went 17-6, leading American Association hurlers in winning percentage (.739). At the plate, he batted a scintillating .370 in 99 games, finishing second in the AA batting title chase to former Chicago White Sox pitcher/outfielder Reb Russell (.385). As the season progressed, major league scouts flocked to Milwaukee to assess the phenom, with the New York Giants emerging as his most likely purchaser.24 Giants manager John McGraw proved unwilling to meet the $50,000 asking price placed on Orwoll. Yet an equally renowned major league skipper was not put off by the steep price that the Brewers wanted: Connie Mack. During an August road trip, Mack left his A’s team in Chicago to personally scout Orwoll during a doubleheader in Milwaukee. A complete-game victory over Indianapolis in the opener demonstrated Orwoll’s pitching talent for Mack. Three base hits and wide-ranging center field defense in the nightcap then cinched Mack’s intent to add Orwoll to the expensive list of past stars and future prospects being gathered by the Athletics boss.25 In return for veteran shortstop Chick Galloway, catching prospect Charlie Bates, a third player to be named later, and a reported $50,000, Mack got his man.26

As he later explained to a hometown sportswriter, Mack was impressed with Orwoll’s pitching but bowled over by the prospect’s play in the second game. “I was amazed with his speed, fly chasing skill and batting power,” said the venerable A’s skipper.27 Likening his new acquisition to New York Yankees star Earle Combs, Mack was undecided whether he would use Orwoll as a pitcher or position player. “It all depends on how the team shapes up,” he said.28

With the 1928 Philadelphia A’s on the cusp of three straight American League pennants, spring camp was stuffed with playing talent and competition for roster spots was fierce. Returning staff members Lefty Grove, Jack Quinn, Eddie Rommel, Howard Ehmke, and Rube Walberg, plus hot-shot minor league acquisition George Earnshaw, would eventually post a combined 1,166 major league pitching victories.29 Available for outfield duty were returning star Al Simmons and aging all-timers Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, as well as reliable veteran Bing Miller and promising rookie George “Mule” Haas. First base, meanwhile, was consigned to slugger Joe Hauser (still on the comeback trail from his broken leg of 1925), with 20-year-old star-in-waiting Jimmie Foxx in reserve. Despite that, the relatively unheralded Orwoll managed to attract a fair amount of press attention,30 including comparison to Sisler and Ruth.31 More important, he played well enough in manager Mack’s estimation to make the club, primarily as a pitcher.

Ossie Orwoll made his major league debut during the second game of the 1928 season, coming on in relief against the defending world champion New York Yankees with the A’s already behind, 5-1. He was greeted rudely by a two-run Bob Meusel home run but then settled down to pitch an effective seven innings in an eventual 8-7 Philadelphia loss. Ten days later, he was less impressive in his first start (six runs in seven innings) but staggered to a maiden major league victory over the Boston Red Sox, 11-6. Used sparingly thereafter as a spot starter/long reliever with mixed results, Orwoll’s stock as a pitcher fell with Mack. A limited repertoire – an above-average fastball but underdeveloped breaking stuff and erratic control – was deemed the left-hander’s primary shortcoming.

In time, however, a prolonged batting slump by Joe Hauser afforded Orwoll a reprieve. With Foxx manning third base for injured regular Sammy Hale and the A’s falling far behind in the pennant chase, Mack decided, in mid-July, to try Orwoll at first. His defensive work proved a revelation. Said Mack: “Orwoll’s a wonder. His fielding at first base has opened my eyes. He makes plays that look impossible. He’s death to ground balls and covers so much territory that it’s almost like having two men out there instead of one.”32 Orwoll also demonstrated that he could hit major league pitching, posting a .300+ batting average, albeit with little power.

With newcomers Foxx, Orwoll, and Mule Haas (who supplanted Cobb in the outfield in late July) leading the way,33 the A’s surged in the standings. They briefly nosed ahead of the Yankees on September 8 when Orwoll entered a tie game in Boston in the bottom of the eighth inning, held the Red Sox scoreless for two innings (retiring six consecutive batters), and singled in the middle of a rally that gave the A’s a 7-6 lead in the top of the 10th inning. He retired the side in order in the bottom of the inning and was credited with the win. At the end of the season, however, the Bronx Bombers prevailed, finishing two and one-half games ahead of the A’s. Orwoll ended the year with a solid .306 batting average, 22 RBIs, and 28 runs scored in 64 games. He had also chipped in a 6-5 record in 27 pitching appearances. But a club-high 4.58 ERA in 110 innings suggested that he was better equipped to be an everyday position player. Whatever the case, Orwol’s future seemed secure at the time. One nationally syndicated commentator called him “the first baseman Mack has been looking for ever since Stuffy McInnis departed” Philadelphia after the 1917 season.34 But unexpectedly, Orwell’s tenure with the club was now closer to its end than beginning.

The mid-winter release of Joe Hauser seemed to cement Orwoll’s status as incumbent A’s first baseman, and given the club’s strong performance the previous season, predictions for a 1929 championship were rampant in the press. But Mack entered spring camp in a strangely sour temper. Injuries and listless club performance in the early exhibition games only darkened the manager’s mood.35 In an April 2 exhibition game against the Southeastern League Jacksonville (Florida) Tars, Orwoll “fielded well … and pounded out a triple, double, and sacrifice fly.”36 But the following day, Mack lit into his charges. Normally supportive of his players, public criticism of them was out of character for the club boss. Odder still was the prime target of Mack’s vitriol – the sober, serious, and gentlemanly Ossie Orwoll. Yet Mack was unsparing, calling Orwoll his “greatest disappointment.”37 His recent first base play had been “positively terrible” and his batting lethargic, Mack complained. Yet later the same evening that Orwoll had underperformed on the field, the irate manager called him “the most energetic player on the club, laughing and cutting up.” The strait-laced Norseman was also cited, improbably, for shoddy “off-field habits” and a “failure to keep in training.”38

As a result, Jimmie Foxx would be installed at first base. Still, Mack intended to retain Orwoll, at least temporarily, and hoped that he would come though. “Personally, he’s a fine fellow,” Mack hastened to add. “He’s a quiet and likeable chap and very popular with the rest of the players.” But Orwoll’s “salvation” with the Philadelphia A’s now “depends wholly upon himself.”39

Unfortunately for Orwoll, he had become a player without a designated position on the A’s. Spring arm problems and manager disdain – “I don’t like Ossie as a pitcher,” Mack had declared only weeks earlier40 – militated against his making the roster as a hurler. As for field positions, slick-fielding singles hitters like Orwoll were now passé at first base, supplanted by home run-bashing sluggers, as embodied by Foxx (and Lou Gehrig). Meanwhile, power hitters Al Simmons and Bing Miller had the corner outfield posts tied down, while center field, probably Orwoll’s ideal position, was assigned to younger, more promising Mule Haas.

When the A’s opened the 1929 season with a 13-4 thrashing of the Washington Senators, Foxx played first base. And there he would stay for the remainder of the year. The everyday outfield of Simmons-Haas-Miller also stayed intact all season. As a result, Orwoll did not make an appearance until ten games into the campaign, and then only as a sore-armed relief pitcher. Two unearned runs cost him a 9-7 defeat to the Yankees on April 27. Widely spaced and spotty relief appearances followed. Beginning in mid-June, Orwoll was also used occasionally as a pinch hitter. He did not play the field until June 30 when he spelled Simmons in left field for a few innings during a 12-2 loss to Washington. A week later, a leg injury suffered by Haas gave Ossie a week’s work as his replacement. Stationed in his optimal spot, Orwoll performed capably, going 9-for-31 (.290), with six runs scored and three RBIs, playing flawless center field defense in a seven-game stretch that ended when Haas returned to the A’s lineup on July 14. Orwoll thereupon returned to the bench.

On August 21, Orwoll pitched late-inning relief in a 7-5 loss to the St. Louis Browns. Days later, he was jettisoned by Mack, optioned back to the Milwaukee Brewers.41 Philadelphia recalled him at season’s end but he saw no further game action – nor would he in future. The major league career of Ossie Orwoll was over. In 94 games spread over two seasons, he posted a respectable .294/.347/.389 slash line with 28 RBIs and 34 runs scored, but exhibited little power. His 18 extra-base hits did not include a single home run. As a pitcher, he went a cumulative 6-7 (.462), with a 4.63 ERA in 136 innings pitched. He struck out 65, walked 56, and surrendered 13 round-trippers. With the glove, Orwoll had been a superior defender at both first base and center field – only six errors in 367 fielding chances at those positions. He also fielded his position well when on the mound, making only one error in 33 chances.

Orwoll did not participate in the pennant-winning Philadelphia A’s triumph over the Chicago Cubs in the 1929 World Series. Nonetheless, his erstwhile teammates voted him a three-quarter ($4,365.96) share of their winnings.42 Shortly thereafter, the Athletics optioned Orwoll to another minor league club with which they had a working agreement – the Portland Beavers of the Class AA Pacific Coast League.43 There, Ossie’s hopes of pitching his way back to the majors were stymied by a season-long sore arm, but he rendered reliable service at first base, batting .301 with 11 homers for the last-place Beavers.

Recalled by Philadelphia at season’s end, Orwoll balked when the Athletics attempted to re-option him to Portland over the winter, filing a grievance with Commissioner Landis.44 Philadelphia thereupon mooted the claim by releasing Orwoll outright to the Beavers.45 But Philadelphia’s hold on the 30-year-old had done its damage, preventing him from hooking on with another major league team for almost two years. Now his prospects for promotion were marginal, at best. Still, he persevered. His arm recovered, Ossie returned to pitching, going 13-16 for Portland. He also filled in occasionally at first base.

Orwoll began a third season with the Beavers in 1932, but a recurrence of arm miseries rendered him ineffective. With his record standing at 0-2, Portland sold him to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association.46 Five atrocious outings – 41 base hits and 23 runs surrendered in 18 innings pitched – promptly earned Ossie his walking papers from St. Paul.47 Abandoning pitching for the time being, Orwoll then dropped down a competitive notch, signing with the Des Moines Demons of the Class A Western League as a first baseman.48 There, he played a competent first base (.988 FA) and batted a modest .271 in 42 games.

No longer with much likelihood of major league employment, Orwoll did not return to Des Moines until mid-June 1933. But once back, his bat revived. In 96 games, he posted a .309 batting average with career highs in home runs (15) and slugging average (.553). He also performed helpful spot duty for an injury-riddled Demons pitching staff, going 4-1 in 14 appearances for the Western League pennant winners. He was even better in a return engagement, batting .322 with 44 extra-base hits in 110 games, while posting an 8-5 pitching record for a weaker, third-place Des Moines club in 1934. In recognition of this standout work, sportswriters covering the circuit for The Sporting News placed the veteran second in a post-season Western League MVP poll.49

Time expired on the Organized Baseball career of Ossie Orwoll the following June. With his batting average shriveled to .236 and his pitching log standing at 1-4, Des Moines released him.50 Within hours, he was back in harness and, starting a beard, was signed by the celebrated House of David team of Benton Harbor, Michigan.51 Over the ensuing four months, Orwoll reportedly won 18 games while batting .380 for his hirsute new club.52

Instead of attending spring training in 1936, Orwoll tried his hand at local Iowa politics. He won the April Republican Party primary for the position of clerk of the Winneshiek County court.53 However, he lost the general election that November to his Democratic rival. As a consolation prize, Republican powers in Des Moines bestowed the state capital doorkeeper sinecure upon him.54 All the while Orwoll continued playing baseball for various area semipro clubs. In 1943, a politically connected job with the Winneshiek County engineers office landed Orwoll in remote Baffin Bay, Canada, for nine months of work on an undisclosed military project.55 Upon his return, he accepted the post of history/gym teacher and athletics director at a high school in Keister, Minnesota.56 During summers, he continued playing for semipro and town ball teams through 1947.57 In the early 1950s, he returned to Decorah and spent the final 18 years of his working life employed by an area meat packing company.58

Shortly after his retirement in 1965, Orwoll was diagnosed with stomach cancer. His final days were spent at Smith Memorial Hospital in Decorah. He died there on the morning of May 8, 1967.59 Oswald Christian “Ossie” Orwoll was 66. Following funeral services conducted at Decorah Lutheran Church, his remains were interred in the town’s Lutheran Cemetery. Newspaper tributes followed, particularly in those places where the deceased had first risen to professional sporting prominence.60 But a more enduring testimonial stands to this day on the Luther College campus overlooking the baseball field. The inscription reads: Ossie Orwoll Memorial Scoreboard – Class of 1925.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info provided herein include the Ossie Orwoll file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Mark Orwoll, “The Iowa Ghost,” Travel and Leisure, October 1990; US Census data and Orwoll family posts accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 A fate, ironically, forecast by a syndicated Brooklyn sportswriter at the dawn of Orwoll’s time as a major leaguer. See Thomas Holmes, “Orwoll Bought by A’s, Has Career Paralleling Bentley’s at Baltimore,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 8, 1927: 24. Although he posted respectable numbers during a nine-season major league career (46-33/.291), Bentley never lived up to his International League hype and was deemed a bust by many contemporary commentators.

2 Ossie’s siblings were brothers Sylfest (born 1899), Erling (Earl, 1904), and Arvid (1908) and sisters Martha (1911) and Alice (1914).

3 Per the player questionnaire completed by Orwoll himself in 1959 and on-line US Army records accessed via Ancestry.com. See also, “Blond Ghost Marvel for Grace,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, March 11, 1928: 36.

4 See “First Base Not New to Orwoll,” Canton Repository, August 24, 1928: 38, and Rockford (Illinois) Register-Gazette, August 6, 1928: 11.

5 Per the 1919 Sioux Falls City Directory.

6 See “Luther Athletes’ ‘Dads’ Also Made Athletic History,” Waterloo (Iowa) Courier, November 8, 1923: 15; “Sons of Former Athletes Play on Luther Grid Team,” Omaha Bee, November 11, 1923: 12; “Orwoll Family Stars for Luther,” Des Moines (Iowa) Register, May 26, 1924: 11. Ossie and Bilt Orwoll were backfield stars on the 1923 Norsemen football team. A generation earlier, father S.M. had also been a star Luther halfback.

7 Short for “Biltmore.” See “Leads Luther Team,” Des Moines Register, March 15, 1923: 11. The origin of the nickname was not discovered by the writer.

8 The Orwoll brothers had briefly been baseball teammates at Luther Normal in 1917. See Sioux Fall (Iowa) Argus-Leader, April 23, 1917: 9.

9 As noted in Orwoll obituaries. See e.g., “Ossie Orwoll, Ex-Baseball Star, Dies,” La Crosse (Wisconsin) Tribune, May 9, 1967: 9.

10 As noted in “Name of Ossie Orwoll Had Magic Ring in ‘Golden Age,’” La Crosse (Wisconsin) Sun, May 14, 1967: 26. See also, Manning Vaughan, “Putting Them on the Pan,” Milwaukee Journal, October 3, 1926: 35.

11 According to Orwoll himself in his 1959 player questionnaire. Both Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet list him as slightly larger at 6’/174 lb.

12 See “Undefeated Luther College Baseball Team,” Minneapolis Star, June 7, 1923: 22 (with team photo).

13 Pitching for a Caledonia, Minnesota club, Dahl threw a four-hitter at La Crosse but lost, 3-1.

14 As reported in “Orwoll Spurns Offer,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 8, 1924: 24. See also, “College Star Turns Down Majors Offers,” St. Louis Star, October 17, 1924: 14.

15 Per a widely published Associated Press wire story. See e.g., “Ossie Orwoll Takes Place in Baseball,” Bismarck (North Dakota) Tribune, December 29, 1927: 7; “Story of Orwoll’s Fast Rise to Majors Reads Like Fiction,” Washington (DC) Evening Star, March 9, 1928: 38.

16 As recalled in “Luther’s Old Rubber to Be Retired,” La Crosse Tribune, April 12, 1936: 12; “34-Year-Old Home Plate at Luther to Be Replaced,” Des Moines Register, April 8, 1936: 8. The no-hitters were originally reported in the (Davenport, Iowa) Times and Des Moines (Iowa) Tribune, May 27, 1925, and elsewhere.

17 Per “Luther Hurler Signs to Play Outfield,” Des Moines Register, May 6, 1925: 10.

18 See “Performances of Orwoll, Henning Are Brilliant,” La Crosse Tribune, September 13, 1925: 17.

19 Per “Orwoll Signs with Milwaukee Brewers; Was Boosters’ Star,” Winona (Minnesota) News, September 16, 1925: 14; “Ossie Orwoll Signs with Milwaukee Brewers Last Night,” La Crosse Tribune, September 15, 1925: 7.

20 Per Orwoll career stats through the 1931 season published in the La Crosse Tribune, March 28, 1932: 9. Baseball-Reference provides no data on Orwoll’s brief tenure with the 1925 Milwaukee Brewers.

21 Orwoll’s .750 winning percentage was matched by Indianapolis’ Carmen Hill (21-7). See “Hill and Orwoll Tie for Pitching Honors,” New York Times, December 15, 1926: 23.

22 As reported in “Ossie Orwoll to Play Pro Football Here,” Milwaukee Journal, September 14, 1926: 23; “Orwoll to Play with Pro Eleven,” (Madison) Wisconsin State Journal, September 14, 1926: 15; and elsewhere. See also, “Orwoll Taking Big Chance on Pro Grid,” La Crosse Tribune, October 10, 1926: 14.

23 Per Manning Vaughan, “Putting Them on the Pan,” Milwaukee Journal, December 26, 1926: 23. Three winters earlier, Borchert had sold the contract of rising American League star Al Simmons to the Philadelphia A’s, and the commerce-minded magnate had taken to promoting Orwoll as “the second Al Simmons.” See e.g., Vaughan, Milwaukee Journal, March 26, 1926: 23.

24 See James J. Murphy, “Orwoll, Hard-Hitting Pitcher, Likely to Land in Livery of Giants,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 24, 1927: 31.

25 Beginning with the $100,000 purchase of minor league pitching star Lefty Grove in mid-1925, Mack expended an estimated $700,000 on the talent needed to return the Philadelphia A’s to the top of the American League heap. Not all that money proved well-spent. See Virgil M. Newton, “Connie Stands Pat After Spending $700,000,” Tampa Times, February 4, 1930: 6. See also, Si Burick, “Si-Ings,” Dayton News, February 8, 1930: 8.

26 According to a widely published Associated Press dispatch. See e.g., “Ossie Orwoll to Join Athletics,” Council Bluffs (Iowa) Nonpareil, December 4, 1927: 19; “Mack Gives Three Men for Orwoll,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, December 4, 1927: 77. Retrosheet puts the Orwoll purchase price at $30,000.

27 James C. Isaminger, “2 Games Convinced Connie on Orwoll,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 7, 1927: 26.

28 Same as above.

29 The 1928 Philadelphia A’s also had seldom-used veteran Bullet Joe Bush and his 196 wins on the roster.

30 See e.g., “Orwoll’s a Handy Man,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Intelligencer, March 20, 1928: 15; “Blond Ghost Marvel for Grace,” Canton Repository, March 11, 1928: 36; “Mack’s New Triple Threat,” The Sporting News, January 26, 1928: 1.

31 See e.g., “Sords Points,” San Diego Evening Tribune, March 15, 1928: 26; “Orwoll Handy Man for Mackmen,” Aberdeen (South Dakota) News, March 20, 1928: 8; “Like Orwoll,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, March 20, 1928: 22.

32 Bill Dooly, “Mack Admits A’s Have a Chance,” Philadelphia Record, August 6, 1928: 24.

33 See “Three Young Players Bolstered Athletics,” New York Times, August 12, 1928: S3. See also, Billy Evans, “Transformation of Orwoll and Foxx Are Not First Connie Mack Put Over,” Beaumont (Texas) Enterprise, September 18, 1928: 30. Ty Cobb’s final start in the A’s outfield took place on July 26. Tris Speaker saw his last outfield action ten days earlier. The two aging greats finished the 1928 campaign as occasional pinch-hitters and then retired.

34 Henry L. Farrell, “Looking Back at the Ball Season,” Evansville (Indiana) Press, September 30, 1928: 35.

35 See “Mack Is Disturbed by Athletics Form,” New York Times, March 19, 1929: 39.

36 Per “May Not Change Lineup,” Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Item, April 2, 1929: 4.

37 Bill Dooly, “Connie Mack Calls Ossie Orwoll His ‘Greatest Disappointment,’” Philadelphia Record, April 3, 1929: 14.

38 Same as above. Mack refused to elaborate on the grounds for his personal criticism of Orwoll but the event that may have originally set off the club boss occurred earlier, a raucous train ride performance by the A’s in-house jazz band (Mickey Cochrane on tenor saxophone; Howard Ehmke and Rube Wahlberg, bass sax; Ossie Orwoll, trumpet, and Phil Wagner, piano). See Walter Trumbull, “The Listening Post,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening Journal, March 13, 1929: 15. The Orwoll family was musically talented. In addition to trumpet player Ossie, also a church and campus choir singer in his youth, his brother Bilt was a locally renowned bass-baritone soloist and a music teacher; brother Earl performed as a pianist; and daughter Barbara became a noted soprano.

39 Dooly, “Connie Mack Calls Ossie Orwoll His ‘Greatest Disappointment,’” above.

40 Same as above.

41 As reported in “Ossie Orwoll Plays Tuesday,” Milwaukee Journal, August 27, 1929: 17; “Ossie Orwoll Joins Milwaukee Today,” La Crosse Tribune, August 27, 1929: 9; “Ossie Orwoll Goes to Brewers; Bevo Is Back,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 26, 1929: 14; and elsewhere. In return, Milwaukee sent journeyman outfielder Bevo LeBourveau to the A’s.

42 Per “Dinner Arranged to Honor Mackmen,” New York Times, October 16, 1929: 40. It was further reported that Philadelphia club brass intended to make up the difference so that Orwoll would receive a full $5,821.60 winner’s share. See e.g., “Orwoll Gets a Full Share,” Milwaukee Journal, October 16, 1929: 24.

43 See “Orwoll Goes to Portland,” Milwaukee Journal, February 2, 1930: 22. See also, L.H. Gregory, “Gregory’s Sport Gossip,” (Portland) Sunday Oregonian, February 2, 1930: 47, and “‘Ossie’ Orwoll to Play with Portland Ball Club,” Sioux Falls Argus-Leader, February 20, 1930: 8.

44 Orwoll’s grievance was based on a three-year farm out limitation rule. See “Ossie Orwoll Protests Sale to Portland Club,” Milwaukee Journal, February 25, 1931: 27. But eventually Landis issued an essentially advisory ruling that rejected the Orwoll grievance. See “Free Agent Fight Lost by Os Orwoll,” (Portland) Oregonian, March 19, 1931: 17; “Orwoll Fails in Attempt to Be a Free Agent,” Sacramento Bee, March 18, 1931: 26. If declared a free agent, Orwoll intended to sign with the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association.

45 See “Orwoll to Portland,” Maysville (California) Appeal-Democrat, February 14, 1931: 8.; “Pitcher Released,” Santa Monica (California) Times, February 13, 1931: 6.

46 As reported in “Orwoll Purchased by St. Paul Club,” Los Angeles Record, June 28, 1932: 8; “St. Paul Gets Orwoll from Coast,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 28, 1932: 17; and elsewhere.

47 See “Ossie Orwoll Gets Release at St. Paul,” Akron (Ohio) Beacon-Journal, July 27, 1932: 14; “Orwoll Released by St. Paul Club,” Minneapolis Tribune, July 27, 1932: 8; “Fire Ossie Orwoll,” Spokane (Washington) Chronicle, July 27, 1932: 3.

48 As noted in “Ossie Orwoll Signed by Des Moines,” Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette, July 30, 1932: 8; “Demons Sell Jim Oglesby; Sign Orwoll,” Des Moines Tribune, July 30, 1932: 9.

49 See “Blue Sox Star Southpaw Gets Annual Award,” (Davenport, Iowa) Quad City Times, October 17, 1934: 15; “Frank Lamanski Chosen Most Valuable Player,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, October 17, 1934: 6.

50 Per “Imps Release Sams, Orwoll,” Des Moines Register, June 19, 1935: 7; “Ossie Orwoll and Sams Released by Des Moines,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, June 19, 1935: 20.

51 As reported by Leo Kautz in “Sport Shots,” Davenport (Iowa) Times, June 21, 1935: 20. See also, “Ossie Orwoll Will Join House of David,” Cedar Rapids Gazette, June 20, 1935: 14; “Orwoll to Join House of David,” Des Moines Tribune, June 20, 1935: 20.

52 Per the Davenport Times, October 15, 1935: 13, complete with photo of a fully bearded Ossie Orwoll.

53 Se “Ticket Named for Winneshiek,” Mason City (Iowa) Globe-Democrat, June 3, 1936: 24.

54 Per “He’s Doorkeeper Now,” Des Moines Register, January 31, 1937, with photo of a nattily attired Orwoll standing at his official post.

55 As revealed in “Orwoll Back in States After Nine Months of Secret Government Work,” La Crosse Tribune, February 4, 1944: 9, and “Ossie Orwoll Back from Baffin Bay,” Cedar Rapids Gazette, February 6, 1944: 11.

56 See “Former Major League Player Is Teacher Now,” Des Moines Register, September 6, 1944: 11; “Ossie Orwoll Takes Keister Mentor Post,” La Crosse Tribune, September 5, 1944: 9.

57 As reflected in “Orwoll Hits as UPWA Wins, 8-0,” Waterloo Courier, June 11, 1947: 14.

58 Per the Orwoll player questionnaire.

59 The Orwoll death certificate lists adenocarcinoma metastases as the official cause of death.

60 See e.g., Lou Chapman “Orwoll Was ‘Merriwell’ in Flesh,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 16, 1967: 15; Kenneth O. Blanchard, “Name of Ossie Orwoll Had Magic Ring in ‘Golden Age.’” La Crosse Tribune, May 14, 1967: 26.

Full Name

Oswald Christian Orwoll

Born

November 17, 1900 at Portland, OR (USA)

Died

May 8, 1967 at Decorah, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.