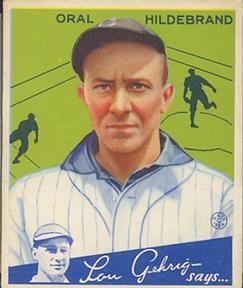

Oral Hildebrand

Six-foot-three right-hander Oral Hildebrand was a .500 pitcher for the Indians and Browns for eight years (1931-38) before landing with the World Champion Yankees and starting Game Four of the 1939 World Series.

Six-foot-three right-hander Oral Hildebrand was a .500 pitcher for the Indians and Browns for eight years (1931-38) before landing with the World Champion Yankees and starting Game Four of the 1939 World Series.

Oral Clyde Hildebrand was born on April 13, 1907, in Indianapolis, Indiana. Asked one time about his unique first name, Oral replied, “I can’t tell you who dug that up.”1 He was the youngest of six children born to Mr. and Mrs. Arnold Hildebrand. Arnold worked as a tenant farmer, employing his two oldest sons (Chester and Lawton) to help him with the necessary tasks. Often, the farms he oversaw were quite large; one in particular was 720 acres.

But Oral had his sights on a different life for himself. After he finished his day at grammar school, Oral would help out with milking the cows, sowing the land — whatever chores needed to be done. But he was a gifted student, who wanted to further his education by attending high school. A high school diploma was a rarity in those days. Arnold sensed that his youngest boy was not cut out for the farm. So on to Southport High School Oral went.

At 15, Hildebrand, or Hildy as he would be commonly referred to, had never played baseball. He didn’t even own a glove until his freshman year. But he took a liking to the sport, and tried his hand at pitching.

But Southport already had an outstanding hurler named Charles Klein, later known as Chuck, the future Hall of Fame outfielder with the Philadelphia Phillies and Chicago Cubs. For the time being, Hildebrand would be placed in the outfield. Klein, who was three years older than Hildebrand, graduated and Hildy was moved over to pitcher.

For the next three years, Hildy was the star pitcher of his Southport team. Arnold was proud of his son, hoping that after graduating, he would return to the farm and possibly move up to work more important tasks, like riding the tractor,

But Hildy nixed those plans, instead choosing to further his path towards a higher education by attending college. But from where would the funds come? For two years, Hildebrand reluctantly returned to a life he despised, but he had little recourse.

In 1928, Hildy received an offer to work in the summer at Stutz Motor Car Company. Hildy convinced his father that he could earn enough money to cover the cost to attend college. Arnold gave his blessing to Oral, and off he went to work in the machine shop at Stutz. He also pitched for the company’s baseball team.

Later that year, he signed on to play baseball with the Indianapolis Power and Light Company in their Sunday league. The team was owned by Norman Perry, who also happened to own the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association. This arrangement enabled Hildy to pay for his college tuition.

Hildebrand took to the hardwood as well. He was the center on Butler University’s National Championship team in 1929. However, such titles were mythical as this predated the present-day tournament format. Hildebrand was also a starting pitcher on Coach Potsy Clark’s baseball team.

However, Hildebrand had participated in several professional baseball games for a team from Brazil (IN) in the summer of 1929. He tried to hide his identity by using the pseudonym of Roy Hilden. An affidavit was presented as evidence that Hildebrand pitched in 11 games for Brazil, receiving $40 for each game. Professor Henry Gelston, chairman of the Butler University Faculty Committee on Athletic Affairs, released a statement: “After a review of the facts as they are listed in the affidavit, which was submitted to us by the Indiana Intercollegiate Conference, charging Capt. Oral Hildebrand with professionalism for playing under an assumed name and accepting money for his services, the Butler University Faculty Committee on Athletics declared Mr. Hildebrand ineligible to compete on teams representing the university.”2

In the spring of 1930, Hildebrand said goodbye to his college days and signed with Perry’s Indianapolis team. He headed off to spring training in Sarasota Florida to begin his “real” professional career.

His first year was a disappointment. Hildebrand went 3-10 with a 4.34 ERA. “I was wild and didn’t amount to much that first year,” said Hildebrand. “Johnny Corriden was manager of the team and he did a lot to bring me around. Bill Burwell, the old right-hander, who once pitched for the Browns, also gave me many pointers. I’ll never forget how he worked me. My personal opinion is that Burwell is one of the smartest pitchers in the game.”3

Hildebrand also tied the knot on October 29, 1930, as he married the former Gladys Morris of Greenwood, Indiana.

Burwell’s tutelage may have had an impact on Hildebrand, as he rebounded in 1931 with an 11-8 record, although his ERA crept up a bit to 5.18. But he also received his big break that season as well. Billy Evans, the former umpire who became Cleveland’s general manager in 1927, had traveled to Wisconsin in an effort to sign Cleveland native Joe Kuhel to a contract with the Indians. But his efforts were rebuffed and Evans traveled back to Cleveland, via a stopover in Indianapolis. He attended a game that Hildebrand was pitching, and even though Hildy was charged with a loss, Evans saw enough that he traded for the tall right-handed pitcher. Hildebrand reported to the Indians and made his major league debut on September 8, 1931, at League Park, pitching 3 1/3 innings of relief to notch his first victory, an 8-7 win over the Chicago White Sox.

Hildebrand stuck with Cleveland in 1932. Perhaps one of the most exciting games of the year came on July 13 at Shibe Park. The Tribe was victorious over Philadelphia in ten innings, 7-5. But it was the crafty pitching of Hildebrand that saved the day. Twice, A’s slugger Jimmie Foxx came to the plate with the bases loaded. In the first inning, Hildebrand walked three to load the bases before bearing down and striking out Foxx and retiring Eric McNair on a force out. In the bottom of the ninth, with the score tied at five, Foxx again stepped into the batter’s box and the bases were juiced. Hildebrand again struck him out, preserving the tie. Hildebrand pitched all 10 innings for the win, striking out five and walking five.

A couple of weeks later, Hildebrand played a part in Cleveland baseball history. The Tribe played its first game at Cleveland Stadium on July 31, 1932. This time the Philadelphia Athletics got the better of the deal, winning the inaugural game at the lakefront stadium, 1-0. Hildebrand hurled a scoreless inning in relief of Indians’ starting pitcher Mel Harder.

Hildebrand made 15 starts in 1932, going 8-6 with a 3.69 ERA. But he lacked control, which was his Achilles’ heel. He walked 62 batters while striking out 49.

Hildy got out to a quick start the following season, winning his first six contests (6-0, 1.69 ERA). Included in this streak was a one-hitter he threw against the St. Louis Browns on April 26. Art Scharein’s single in the top of the third inning was the Browns’ only safety. Hildebrand struck out five and walked two in a game that had a sprinter-like quickness to it, finishing in 1:22.

On June 8, Cleveland manager Roger Peckinpaugh was replaced by Walter Johnson. Peckinpaugh had managed the Indians to a 26-25 record and they were currently in fifth place in the AL standings. Johnson had managed in Washington and had some success. He finished in second place twice and third place once and had a win-loss record of 350-264 in four seasons. Peckinpaugh, a former shortstop and teammate of Johnson’s in Washington, was viewed as a players’ manager. Johnson was not of the same mindset.

The first All-Star Game was played on July 6, 1933, at Comiskey Park. Hildebrand was selected with teammates Wes Ferrell and Earl Averill to represent Cleveland on the American League team. Neither Hildy nor Ferrell saw any action. Averill was used as a pinch-hitter in the sixth inning. He knocked in a run as the AL prevailed, 4-2.

On July 12, Hildebrand got the start against the Athletics at Shibe Park. He lasted 2/3 of an inning, giving up three hits and two earned runs. Hildebrand claimed that his arm was sore and he needed to rest before making another start. But Johnson was having none of it, and started Hildy anyway. Johnson denied that he forced Hildebrand to start that day, but the war of words between the two was just beginning.

On July 31 at Sportsman’s Park, Indians’ pitcher Belve Bean walked the bases loaded in the seventh inning. At the time, Cleveland was leading, 8-4. Johnson summoned Hildebrand, who promptly gave up three walks, one hit and four runs in 1/3 of an inning. When Johnson came out with the hook for Hildebrand, words were exchanged between the two. Johnson ordered Hildebrand to leave the clubhouse and suspended him. The Browns scored eight runs in the frame to take the lead, 12-8, and eventually won the game.

“I don’t want to pitch for Walter Johnson anymore, but if I have to I’ll take it and like it,” said Hildebrand. “But I’m not quitting baseball. I’ll be pitching when Johnson is back digging ditches! I’ll finish out the season, but next year if Johnson is here, I don’t want to be. I’ll ask to be traded to some other club.”4

Hildebrand returned to Cleveland to meet with Evans. Hildebrand was hoping to be traded to get away from Johnson. If he was looking for an intervention from Evans, he was mistaken. Evans informed Hildy that the matter was between Johnson and himself. The front office would be staying clear of their discontent. Evans also let Hildy know that he was staying put, and he would not be released nor traded.

Hildebrand went to Indianapolis to serve out his suspension, returning to pitch on August 6 at Detroit. He apologized to Johnson and the matter was put to rest. “He didn’t seem to care whether I was ruining my arm or not,” said Hildebrand. “I don’t think that’s the way to run a team. Johnson is a nagger and there are plenty of other boys complaining on the quiet.” 5

Hildebrand finished the year with a 16-11 record and a 3.76 ERA. The1933 season was the only one in Hildebrand’s time in Cleveland that his strikeouts outnumbered his walks. And that was by a small margin, 90-88. He led the AL in shutouts with six.

Cleveland finished in third place in 1934 and 1935, and fifth in 1936. Johnson was let go in August of the 1935 season when the team went off the rails. He suspended Willie Kamm and released Glenn Myatt because they were, in Johnson’s opinion, a negative influence to the rest of the team. “Johnson Fails to Win Team’s Respect,” shouted a headline in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on May 24. “Deeply Rooted Antipathy Can’t Be Cured by Firing Few Players,” was the sub-headline.

For Hildebrand, he went 30-28 with a 4.45 ERA from 1934-1936. He was mostly used as a third or fourth starter behind Harder, Johnny Allen, Monte Pearson or Willis Hudlin. Hildy was used out of the bullpen as well, as he accounted for 10 saves during this period.

On January 17, 1937, Hildebrand was packaged with shortstop Bill Knickerbocker and outfielder Joe Vosmik and sent to the St. Louis Browns for pitcher Ivy Andrews, shortstop Lyn Larry and outfielder Moose Solters. “I was mainly in relief roles while with Cleveland and I’m looking forward to getting a regular turn on the mound with the Browns,” said Hildy.6

“Hildebrand is a fastball pitcher with an effective curve, and, I believe, will be a much better pitcher than he was last season,” said Browns manager Rogers Hornsby.7

Indeed Hildebrand led the Browns in starts with 27 in 1937. It was the most starts he made in three seasons. He was shelled for an 8-17 record and a 5.14 ERA. He was the losing pitcher in nine of his final 11 games. The pitching staff had a team ERA of 6.00. The 1937 St. Louis Browns were a terrible bunch, as their 46-108 record indicated. It was the 18th worst record in baseball’s modern era (1900-present). Hornsby was replaced at mid-year by Jim Bottomley.

Gabby Street took the reins the next season, but the results did not change much in the Gateway City. The Browns did finish in seventh place ahead of Philadelphia. Their record improved to 55 and 97, 44 games off the pace. Hildebrand posted an 8-10 record with a 5.69 ERA.

On October 26, 1938, Hildebrand, was dealt with outfielder Buster Mills to the New York Yankees in exchange for catcher Joe Glenn and pitcher Myril Hoag. In one day, Hildy may have thought he went from the outhouse to the penthouse.

Hildebrand was a spot starter for the Yankees, and one of those occasions was on April 30, 1939. The Senators were the opposition and had defeated Hildebrand on April 22 by a score of 3-1. The Senators won again 3-2, to sweep the brief two-game series. The game marked the final appearance of Lou Gehrig in a baseball game. The Yankees traveled to Detroit after the Washington series, which is where Gehrig approached New York skipper Joe McCarthy and requested he be replaced in the Yankee lineup for the first time in 2,130 games.

Hildebrand was 10-4 with a 3.06 ERA for the Yankees in 1939. He also saved two games and his strikeouts outnumbered his walks, 50 to 41. The Yankees easily won the American League in 1939, outdistancing Boston by 17 games. For Hildebrand, it was his first taste of a World Series . Asked about how he liked being on the Yankee pitching staff, Hildebrand replied, “I like it a whole lot. I always wanted to be with the Yankees. When I was with the Indians, and later with the Browns, Joe McCarthy was just another manager of a rival team, in my estimation. Still, I always admired the way he ran his team, and I hoped some day I would be playing for him.”8

Their opponent was the Cincinnati Reds. The Bronx Bombers had won the last three world championships. They defeated the Giants in 1936 and 1937 and swept the Cubs in 1938. Red Ruffing, who had won Game One, had come down with aches and pains and was unavailable to make another start. This thrust Hildy into a starting spot for Game Four at Crosley Field. The Yankees had won the first three games and Hildebrand was called on to nail down a fourth consecutive championship.

Hildebrand did his part, pitching four innings of shutout baseball. He struck out three and walked none. He was removed from the game, it was reported, because he twisted his right side. The game was tied at four after nine innings. But in the top of the tenth, the Yankees scored three runs to take a 7-4 lead. The lead held up, and they had their fourth World Championship in a row, and eighth in franchise history.

On October 20, Hildebrand was involved in an automobile accident, when his car collided with a station wagon in Indianapolis. It was a foggy night and the visibility was very low. There were four women in the wagon, and they suffered skull fractures, a broken back and other serious injuries. It was believed that two of the women would not survive. Hildy suffered injuries to his hands and arms. No charges were filed.

Hildebrand’s last season in the major leagues was 1941. He pitched entirely out of the bullpen, appearing in 13 games. For his career, Hildebrand’s record was 83-78 with a 4.35 ERA. He struck out 527 batters while walking 623.

The Yankees traded him to St. Paul of the American Association on March 30, 1942. The next season he pitched in four games for Indianapolis.

After Hildebrand retired from baseball, he began a career as a tool and die maker. He worked for the Link-Belt Division of the FMC Corp, which he retired from in 1972. Oral Hildebrand passed away at his home in Southport, Indiana, on September 8, 1977. He was survived by his second wife, Frances, and five children: Barbara, Laura, Oral C. II, Thomas and James.

It was once suggested to Hildebrand that maybe it was the chores he did around the farm that built up his strength, especially in his fingers and wrists. “Maybe milking did help me as a pitcher,” said Hildy. “But I’ll never recommend it to anyone I like.”9

It seemed clear. Oral Hildebrand had made the correct career choice.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Dick Farrington, “From Hoosier Farm Boy To Big Leaguer”, The Sporting News, January 11, 1934: 3

2 “Ineligibility, Illness and Graduation Wreck Butler Basketball Team”, Indianapolis Star, February 7, 1920: 12

3 Farrington, “From Hoosier Farm Boy To Big Leaguer”

4 Scott H. Longert, No Money, No Beer, No Pennants: The Cleveland Indians and Baseball in the Great Depression, Ohio University Press, Athens, OH, 2016, 194

5 Ibid.

6 Max Greenwald, “Trade Gratifying to Hoosier Hurler”, Indianapolis Star, January 18, 1937: 14

7 “Hildebrand Sent to Browns As Part of Major Deal”, Indianapolis Star, January, 18, 1937: 14

8 Edward T. Murphy, “Noiseless Oral Speaks Out”, Baseball Hall of Fame, players file

9 Farrington, “From Hoosier Farm Boy To Big Leaguer”

Full Name

Oral Clyde Hildebrand

Born

April 7, 1907 at Indianapolis, IN (USA)

Died

September 8, 1977 at Southport, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.