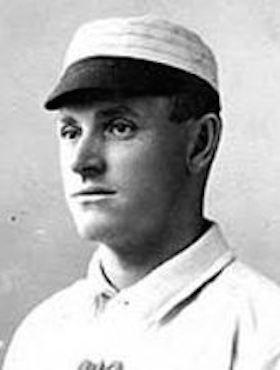

Billy Hamilton

Billy Hamilton was the greatest base stealer and most prolific run scorer of nineteenth-century baseball, but few recognized his name when he gained admittance to the Hall of Fame long after his death. Bill James, who ranks Hamilton as the ninth-best center fielder of all time in his book, The New Historical Baseball Abstract (1999 ed.), remarked on the anonymity of the man called “Sliding Billy.”

“Hamilton was completely invisible in the literature of the sport up to 1960,” wrote James, “and was not elected to the Hall of Fame until 1961. He left no legend behind him, no stories, no anecdotes … Hamilton was eventually elected to the Hall of Fame purely on the overwhelming quality of his numbers. Even now, in books about nineteenth-century baseball, he is often not mentioned at all, and is never presented as a fully-formed character.”1

William Robert Hamilton, the son of Scottish immigrants Samuel and Mary Hamilton, was born in Newark, New Jersey, on February 16, 1866. Billy was the first of two children, the other being his sister, Mary, born two years later. By 1870, the Hamilton family had settled in Clinton, Massachusetts, an industrial town in the hub of the New England textile industry. Clinton was a textile-producing town with several large factories that produced gingham, rugs, and carpeting. Samuel Hamilton found work in a textile mill. By the time Billy was 14 years old, he had quit school and joined his father in the mill.

A left-handed batter and a left-handed thrower, Billy excelled in the semipro leagues around Clinton as a teenager. He stood only 5-foot-6 as an adult, and weighed 165 pounds, but his thick, muscular legs made him appear heavier. Those powerful legs became his greatest asset. He was an incredibly swift runner, and was usually the fastest man on the field in any game he played. He learned to use his speed to beat out bunts, steal bases, and cover large amounts of ground in the outfield. Billy was more interested in playing ball than in building a life as a textile worker, and he realized that his speed was his ticket out of the mill.

His first professional engagement came in 1887 with Lawrence of the New England League, a team that moved to Salem in mid-July to finish the season. The 1888 campaign found Billy in center field for Worcester, also an entry in the New England League. He batted .351, scored 76 runs, and stole 72 bases in only 61 games. His offensive prowess marked him as a future star, and in July of that year Worcester sold his contract to the Kansas City Cowboys of the American Association, one of the two major leagues in 1888. On July 31, Billy made his debut in right field against the Philadelphia Athletics, batting leadoff and going hitless against veteran pitcher Gus Weyhing, who pitched a no-hitter against the hapless Cowboys that day. The 22-year-old rookie played in 35 of Kansas City’s remaining 58 games that season, batting .264 and stealing 19 bases for the last-place club.

Installed as Kansas City’s regular right fielder and leadoff batter for the 1889 season, he posted a .301 average and a league-leading 111 steals. His totals cannot be compared to those compiled in the present day, since stolen bases then included advancing on fly balls and taking extra bases on errors. Still, Hamilton’s 111 thefts, 20 more than the second-highest total in the Association that season, marked him as one of the rising stars of the game. Kansas City moved up a notch to seventh place, in large part due to the inept Louisville team falling behind them, but the ball club lost money and disbanded at season’s end. On January 7, 1890, Kansas City sold Hamilton’s contract to the Philadelphia Phillies for $5,000.

The Phillies (known as the Quakers prior to 1889) were harmed, as was nearly every other National League team, by the Players League revolt of 1890. Many of the 1889 Phillies had deserted the club and signed with the new league, though the team managed to retain such key performers as home run champion Sam Thompson, pitcher Kid Gleason, and catcher Jack Clements. Manager Harry Wright and team owners John I. Rogers and Al Reach filled the holes on the roster with minor-league imports and acquisitions from other teams. Wright installed Billy Hamilton as the left fielder and second-place hitter, with rookie center fielder Eddie Burke in the leadoff spot.

Hamilton displayed both his strengths and his weaknesses to the Philadelphia fans. On the basepaths, the 24-year-old Hamilton “tried to steal everything in sight, including the umpire,” as one paper put it. His spectacular slides brought cheers from the fans and resulted in his nickname, “Sliding Billy.” He had the go-ahead to steal at any time, not that he needed any encouragement. “Hamilton’s work on the basepaths was spectacular; he delighted in stealing bases,” said his outfield mate, Sam Thompson, years later. Thompson, who played a few games for the Detroit Tigers in 1906, claimed that Hamilton was “more daring and reckless” than Ty Cobb.2 In mid-May, Hamilton and Burke switched places in the lineup, with Billy now batting leadoff.

Hamilton’s speed and bunting skill kept his batting average above the .300 mark, but his fielding was sorely lacking. He led the league in outfield errors in 1890, and his fielding percentage of .882 was one of the worst in the league. He chased the ball well enough, but dropped many flies, while poor throws plagued him all season long. One Philadelphia sportswriter complained in May that Hamilton “omitted to close his hands properly at different times,” after he committed two errors in a game against Brooklyn.3 Despite these shortcomings, he batted .325 and led the third-place Phillies and the National League with 102 steals.

In 1891, the Players League refugees came streaming back to the National League following the demise of that circuit, and the best-hitting outfield in major-league history was complete with Ed Delahanty’s return to Philadelphia’s center field. “Big Ed” was a native of Cleveland who joined the Phillies in 1888 and jumped to Cleveland’s Players League entry in 1890. He was a muscular, hard-hitting, right-handed batter, and while he was not much better in the outfield than Hamilton, he owned a stronger throwing arm. Sam Thompson, the right fielder, also was no defensive standout, but when he joined with Hamilton and Delahanty, Philadelphia boasted an offensive powerhouse no other National League outfield could match.

Hamilton’s defensive play improved in 1891, with his error total dropping and his fielding percentage rising, but his main contribution to the Phillies was still on offense. He captured the league batting title with a .340 mark that year, while leading the circuit in hits (179), runs scored (141), and stolen bases (111). He was a disruptive force, particularly with his ability to frustrate opposing pitchers by fouling off their deliveries until he found one to hit or drew a walk. He was the ideal leadoff man, getting on base in more than 45 percent of his plate appearances that season, and putting himself in position to be knocked in by sluggers Delahanty and Thompson.

Though the Philadelphia pitching was too weak for the team to mount a serious challenge for the pennant, the offensive fireworks drew fans. The flashy Billy Hamilton was one of the most popular players on the team. In 1892, all three outfielders batted over .300, with Hamilton leading the way at .330. In 1893, after the pitching distance increased ten feet to the current 60’ 6” standard, their batting averages soared. His outfield defense improved as well, and in 1893 Harry Wright, in his final season as manager, moved him to center field, and sent Ed Delahanty to left. Billy remained in center for the remainder of his major-league career.

Baseball scholars do not know how many times Sliding Billy was tagged out while trying to steal, as such statistics were not kept until the twentieth century. But newspaper accounts indicate that his rate of success was remarkably high. As The Sporting News reported in 1898, “[Hamilton] has got base stealing down to a science, and no player succeeds in the attempt so often in proportion to times attempted. His slide is wonderful, and often he gets away from the fielder when the latter has the ball in hand waiting to touch him.”4 They called it the “fadeaway slide,” and while Hamilton may not have invented it, he was its most skilled practitioner. Billy’s base-running exploits, while delighting fans, frustrated and embarrassed his opponents, and made him unpopular on the field. During one game against the Cleveland Spiders, third baseman Chippy McGarr became so angry with Hamilton that he picked up the diminutive Phillie, carried him to the stands, and tossed him over the railing and into the seats.

If anyone still needed confirmation of Hamilton’s value to the team, they received it in 1893. He was on his way to another outstanding season in early August, and the Phillies stood in second place after three double-digit drubbings of the Senators. Hamilton had complained of not feeling well, and his health grew worse as he tried to play despite fever and fatigue. On August 10, a doctor diagnosed Hamilton with a case of typhoid fever and ordered him out of the lineup. Billy played no more that season, and the Phillies fell out of the race, going 19-26 the rest of the way, and settling into fourth place.

Manager Arthur Irwin, who succeeded Harry Wright, scoured the minors for pitching prospects before the 1894 season started. But although Phillies displayed the most incredible hitting attack ever seen, with all their outfielders batting .400 or better, their mediocre pitching kept them back in third place. Thompson, who missed a month after finger surgery, hit .415 and drove in 147 runs; Delahanty batted .404, and substitute Tuck Turner turned in a .416 average. As for Billy Hamilton, he rode the crest of the offensive wave to score 198 runs, the highest total ever achieved in the major leagues, which has never been challenged seriously since. Hamilton also became the first player to reach base in more than half of his season plate appearances; his .521 on-base percentage stood as a record until Baltimore’s John McGraw passed it four years later.

The official statistics at season’s end gave Hamilton a batting average of .399 on 223 hits in 559 trips to the plate. He missed the .400 circle by one hit. Statisticians have since revised the numerical records of long-ago games, correcting errors and discrepancies, and determined that he actually had 225 hits in 558 trips, putting his average at .403. Though major-league baseball, and the Baseball Hall of Fame web site, still list his 1894 average at .399 (with 196 runs scored), the researchers at Retrosheet.org put Hamilton in the .400 class with his outfield mates.5

Hamilton’s 1894 season was remarkable in many ways. From July 6 to August 2, he scored at least one run in 24 consecutive games for the hot-hitting Phillies. On August 31, he tied George Gore’s 13-year-old major-league record with seven stolen bases, leading the Phillies to an 11-5 win over the Senators. He also compiled a 36-game hitting streak, the longest in Phillies team history until Jimmy Rollins matched the feat in 2005. But Hamilton quarreled with manager Arthur Irwin, with Irwin complaining to the papers that he was a “disorganizer.” The Phillies finished nine and a half games behind Baltimore and seven in back of the Cleveland Spiders. Irwin was dismissed, and on November 14, 1895, in one of the worst trades in Philadelphia baseball history, the Phillies sent Hamilton to the Boston Beaneaters for third baseman Billy Nash, who replaced Irwin as manager of the ballclub.

Boston manager Frank Selee, seeking to replace the aggression of Tommy McCarthy (recently traded to Brooklyn), put Hamilton in the leadoff spot and gave him free rein on the base paths. His speed and enthusiasm energized the Boston lineup, and his .366 average and 153 runs scored led the Beaneaters to a fourth-place finish in 1896. In 1897, Selee promoted two young pitchers, Ted Lewis and Fred Klobedanz, to regular roles in support of the staff ace, Kid Nichols; suddenly Boston owned the best starting pitching in the league. Third baseman Jimmy Collins and first baseman Fred Tenney solidified the infield, while rookie Marty Bergen took over as the regular catcher. Boston was now the most balanced team in the National League. After a strenuous battle with the defending champion Baltimore Orioles, the Beaneaters won their first league title since 1893, making Hamilton a pennant-winner for the first time in his career.

Hamilton was now the centerpiece of a new all-star outfield, with Hugh Duffy in left and rookie Chick Stahl, who batted .354 and scored 112 runs, in right. Hamilton was a major contributor to the championship team, leading the league with 152 runs scored and 105 walks. On September 27, with the pennant on the line in the final contest of a three-game series with Baltimore, he swatted four hits, scored three runs, and stole two bases in a 19-10 win. That virtually sewed up the flag for Boston. The Beaneaters wound up winning the pennant by two games over the Orioles.

Hamilton loved playing for the Beaneaters, as Boston was only an hour by train from his home in Clinton. Billy had married a local girl named Rebecca Carr in 1888, and by 1896 they had three daughters: Ethel, Mildred, and Ruth. A fourth daughter, Dorothy, was born in 1904, completing the family. The Hamiltons made their home in Clinton for more than three decades, and he often took the train to Clinton on off-days during the season.

The Beaneaters repeated as champions in 1898, but Hamilton’s legs were beginning to wear down. A sprained knee limited him to 110 games in a 152-game season; batted .369 and scored 110 runs. A more serious injury in 1899 — a tendon problem in his lower leg that developed after he wrenched his knee while sliding in early May — shortened his 1899 season and put his career in jeopardy. He played only 84 games, and saw his batting average fall to .310. His stolen base total dwindled to 19. At age 34, Hamilton managed to play the entire 1900 season without a serious injury, batting .333, but with only 32 stolen bases. Frank Selee still batted him in the leadoff slot, but his days of scoring more than a run per game were over. He was slowing down noticeably, and the Beaneaters fell to sixth place.

When the American League began play in 1901, most of the Boston stars bolted to the new circuit, leaving Selee with a shell of a team. Hamilton, however, turned down all offers and remained with the Beaneaters for one more season. He was now 35 years old, and his batting average sank below the .300 mark for the first time since 1888. He stole only 20 bases in 102 games for the seventh-place Beaneaters, and at the end of the season he requested and received his release.

Few observers paid attention to lifetime statistics and career records 100 years ago, but Billy Hamilton’s numbers marked him as one of the greats. He retired as baseball’s all-time leader in walks, a distinction he held until Eddie Collins passed him in 1922. His .344 career batting average is the eighth highest of all time, and his on-base percentage of .455 is surpassed only by Ted Williams, Babe Ruth, and John McGraw. Hamilton’s career stolen bases, once recorded as 937 and later revised to 914, stood as a major league record until Lou Brock, who retired in 1979 with 938 steals (under different rules). During his 14 years in the majors, Billy scored 1,697 runs in 1,594 games, and his average of 1.06 runs per game is the highest figure ever recorded. Only three men (Hamilton and fellow nineteenth-century stars Harry Stovey and George Gore) scored more than one run per game during their careers, and no modern player has come close to matching the feat.6

Billy Hamilton was gone from the majors, but not from the game. In June 1902 he was hired to manage and play for the New England League team in Haverhill, Massachusetts. He remained with Haverhill for three seasons, playing on a part-time basis in 1902 and 1903, and becoming a full-timer in 1904. His 1903 team finished last, but he led the team to the pennant in 1904. At the age of 38, he won the batting title with a .412 average, and led the league in stolen bases and runs scored.

This success at Haverhill led to a position at Harrisburg in the Tri-State League, but disputes both with the team owners and players led to his ouster in mid-1906. The old ballplayer then returned to Haverhill, where he played and managed until 1908, winning another batting title. He spent the next two seasons with another New England League team, the Lynn Shoemakers, before he finally retired as a player after the 1910 campaign.

Hamilton spent the 1911 and 1912 seasons scouting for his old Boston team (who became the Braves in the early 1910s), and then managed for Fall River and Springfield in the New England League in 1913 and 1914. In 1916, he bought a part-interest in the Worcester ballclub and moved his family there, managing the team for one season. Billy sold his interest in the club in March 1917 and never returned to the game. He and wife, Rebecca, resided in Worcester for the rest of their lives. The old ballplayer obtained a position as a production foreman at a local leather manufacturing plant, where he worked until the early 1930s. He battled heart disease after his retirement from the factory. Mostly confined to bed for the last year of his life, Billy Hamilton died at home in Worcester on December 16, 1940, at the age of 74. His wife, who lived until 1957, survived him, as well as four daughters and two grandchildren.

On July 24, 1961, 21 years after his death, three of his children represented him at his Hall of Fame induction ceremony in Cooperstown.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin.

Last revised: September 21, 2022 (zp)

Notes

1 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001), 728.

2 Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker (editors), Nineteenth Century Stars (Kansas City, Missouri: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989), 75.

3 Brooklyn Eagle, May 10, 1890.

4 The Sporting News, June 4, 1898.

5 This statistical information was obtained free of charge from and is copyrighted by Retrosheet. Interested parties may contact Retrosheet at http://www.retrosheet.org.

Full Name

William Robert Hamilton

Born

February 15, 1866 at Newark, NJ (USA)

Died

December 15, 1940 at Worcester, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.