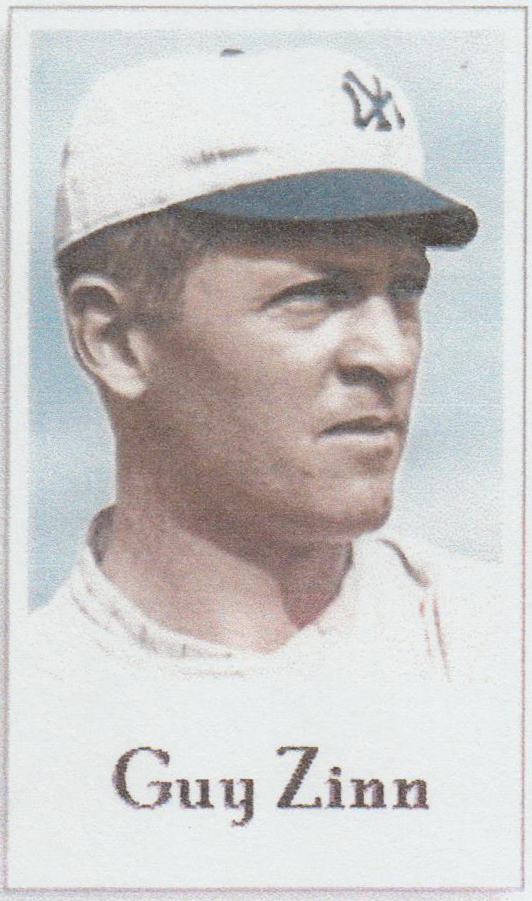

Guy Zinn

Handicapped by attitude and injury problems, Deadball Era outfielder Guy Zinn never achieved the success predicted for him. Nevertheless, his time in the game was not without modest distinction. On Opening Day 1912, New York Highlander Zinn became the first major-league player to enter the batter’s box; the first to reach base; and the first to score a run in just-constructed Fenway Park. Later that season, he became one of only 11 players in big-league history to steal home twice in the same game. Thereafter as a Baltimore Terrapin in 1914, Zinn scored the first run ever tallied in the renegade Federal League.

Handicapped by attitude and injury problems, Deadball Era outfielder Guy Zinn never achieved the success predicted for him. Nevertheless, his time in the game was not without modest distinction. On Opening Day 1912, New York Highlander Zinn became the first major-league player to enter the batter’s box; the first to reach base; and the first to score a run in just-constructed Fenway Park. Later that season, he became one of only 11 players in big-league history to steal home twice in the same game. Thereafter as a Baltimore Terrapin in 1914, Zinn scored the first run ever tallied in the renegade Federal League.

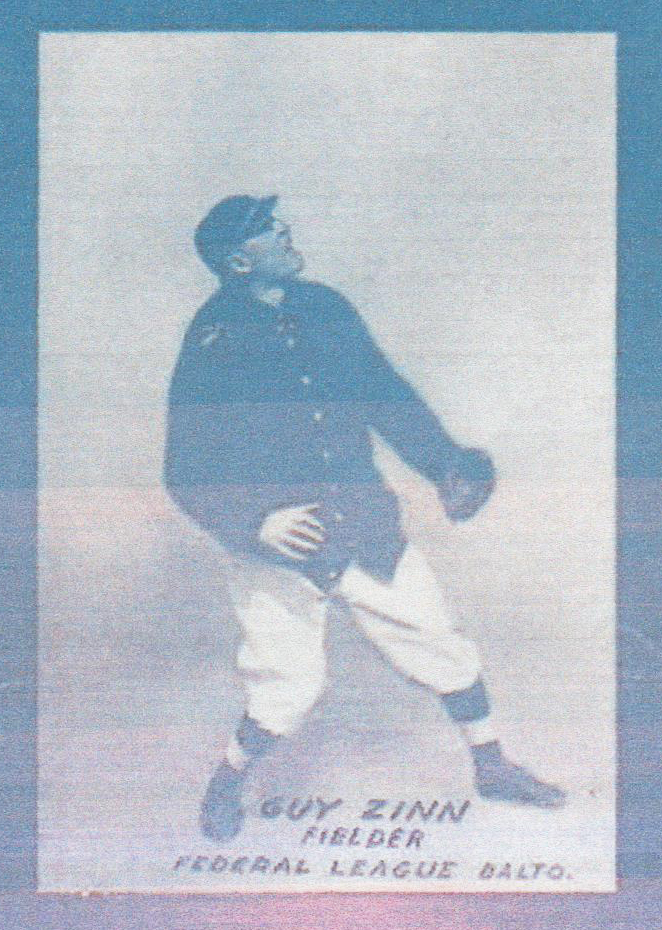

Another distinction once ascribed to Zinn proved illusory. He was long recognized as the only Jew ever to play in the Federal League — until it was discovered that Zinn was not Jewish. This revelation, in turn, vastly deflated the six-figure price tag attached to a rare 1914 Guy Zinn baseball card, earlier the subject of a nasty 2016 dispute between memorabilia collectors that drew the attention of both the New York Times and The Times of Israel. As the religion/baseball card controversy swirled, its focal point was safely in his grave, Zinn having died in October 1949. The story of Guy Zinn’s life and the posthumous controversy that arose over his religion and the effect that it had on the value of his baseball card follows.

Guy Zinn was born on February 13, 1887, in Holbrook, an isolated hamlet located about 40 miles southwest of Clarksburg, West Virginia.1 He was the second of eight children born to carpenter Noah Zinn (1859-1947) and his wife, the former Elizabeth Bee (1861-1932).2 Although the surname Zinn was German, most of Guy’s forebears were Seventh Day Baptists of English and Welsh stock who began arriving in the Virginias in the late 1740s.3 Shortly after Guy’s birth, the family relocated to Clarksburg, a bustling county seat with an active baseball scene. There, he attended school through the sixth grade before entering the local work force. Like his father and brothers, Guy would spend his non-baseball working life in the building trades, usually as a lathe operator.

As a youngster, Zinn devoted leisure time to playing ball for sandlot clubs, often with his older brother Romeo.4 Guy was a good-sized teenager (later officially listed at 5-feet-10½, 170 pounds, but probably a bit larger).5 He batted left-handed and threw righty.

Zinn first came to press attention in 1906 as an outfielder-pitcher for Clarksburg’s entry in the area amateur league.6 He got his first taste of major-league pitching that August when Clarksburg dropped a 5-0 exhibition game decision to the visiting Cincinnati Reds, going 1-for-4 against right-hander Charley Hall.7 Zinn made his professional debut the following spring, signing with the Clarksburg club in the Class D Western Pennsylvania League.8 He made a favorable impression as an outfielder in the early going but was released after suffering a injury to his throwing arm. While his arm recovered, Zinn played summer ball for the semipro Clarksburg Americans.9

In spring 1908, Guy regained a roster spot with the local minor-league club, now called the Clarksburg Drummers and a member of the newly organized Class D Pennsylvania-West Virginia League.10 But again his tenure was short-lived, player-manager Ferd Drumm “having handed him the scarlet slip” in mid-May.11 By then, Zinn was a married man, having taken Ethel Carter as his bride in December 1907. In time, the couple had two children, Buster (Guy A., born 1909) and Jean (1910), whom Guy supported by working offseason lathe jobs.

In 1909, the 22-year-old Zinn finally got a firm foothold on the professional baseball ladder with the Grafton (West Virginia) club in the P-WV League. He saw regular playing time in the outfield and batted a solid .294 in 88 games. He also stole 19 bases. The hometown newspaper of a league rival reported that Zinn, “besides being a star in left field, was great [with] the bat and a good baserunner. His throw from left field to the plate was also a much admired feat.”12 A national journal concurred, informing readers that Zinn has “developed into a great batter and a fine baserunner.”13

In spring 1910, Zinn jumped up to Class A ball, acquired by the Memphis Turtles of the Southern Association for the standard $300 draft price.14 But he found the pitching much harder to hit, posting a disappointing .232 batting average in 43 games with Memphis. Demoted to the Macon (Georgia) Peaches of the Class C South Atlantic League, Zinn again underperformed with the bat, hitting only .229 in 71 games. Still, Toledo Mud Hens President Bill Armour had taken a fancy to Zinn and acquired him for his Class A American Association ballclub in August.15 Zinn raised his batting average to .245 in 19 games with Toledo, but after the season a dissatisfied Armour sold his contract to the Altoona (Pennsylvania) Rams of the Class B Tri-State League.16

Guy got his career back on track in Altoona. He batted a robust .317, with 32 extra-base hits in 106 games played for the Rams. In mid-August, Zinn was purchased for a reported $1,000 by the middle-of-the-pack New York Highlanders of the American League.17 Initially, the plan was for him to complete the Tri-State League season with Altoona before reporting. But soon injuries left the Highlanders short of outfielders, affording Zinn playing time once he arrived in New York.18 He made his major-league debut on September 11, going 1-for-4 (a single) against future Hall of Famer Chief Bender in a 12-5 loss to the Philadelphia A’s. Thereafter, Zinn was not given much further look by playing manager Hal Chase, appearing in only nine games (six starts) total, and failing to impress with a meek .148 (4-for-27) batting average. Yet New York retained hope that the still-promising prospect would blossom, placing him on the club’s reserved list for the 1912 season.19

With a good-hitting outfield (Birdie Cree, .327; Harry Wolter, .304: Bert Daniels, .286) slated for encore duty, competition for the remaining Highlanders outfielder spot was keen the following spring. Ex-Philadelphia Phillies slugger Fred Osborn was Zinn’s principal competition for that coveted slot. New York sportswriter Bill Macbeth had no doubt regarding who his choice would be. In a syndicated column, Macbeth wrote, “Zinn is a far better outfield proposition [than Osborn]. While not as strong a hitter, he is a finished fielder, a fine thrower and a fast man on the base paths.”20 A strong training camp performance by Zinn brought new Highlanders manager Harry Wolverton to the same conclusion, and Guy made the club.

Another round of outfield injuries placed Zinn in the Opening Day lineup. On April 20, 1912, the Boston Red Sox inaugurated a brand-new ballpark by hosting New York. The first player to set foot in the Fenway Park batter’s box was left fielder Zinn. Drawing a walk off Red Sox right-hander Buck O’Brien, Zinn then became the ball park’s first baserunner. And when later driven home by Roy Hartzell’s single, Zinn scored the grounds’ first run. In the century-plus that has since elapsed, the number of major-league ballplayers who have entered the batter’s box, reached base, or scored a run at venerable Fenway Park is near countless. But the first player ever to accomplish these feats will forever be Guy Zinn. Unhappily for him, he did not reach base again, going 0-for-5 in the Highlanders’ 7-6, 11-inning defeat.

Better days, however, were on the horizon for our subject. With Cree and Wolter sidelined, Zinn remained in the lineup, and he quickly began to hit — often in the clutch. Three times in the early going, he came through with base hits in the ninth inning or later, producing New York victories.21 Zinn also supplied the club with some much-needed power (31 extra-base hits) through midseason. During an August 15 win over Detroit, Zinn stole home twice off Tigers right-hander Jean Dubuc.22 In so doing, he became one of only 11 players in modern major-league history (since 1901) to steal home twice in the same game.

To the sporting press and American League fans, the newcomer seemed on his way to stardom, “one of the finds of the year” in the estimation of a Washington newspaper.23 A Cleveland paper concurred, declaring, “Zinn gives promise of development into a great batter. He hits the ball hard and what is more, does his hitting in the pinches.”24 The chorus of praise even extended to the sticks — a backwater Kansas weekly called him “one of the most promising players possessed by any club in the country.”25

But uncorrected Zinn deficiencies undermined the esteem of manager Wolverton. Despite being fleet of foot and a capable fly-ball catcher, Zinn was a substandard (.893 FA) defensive outfielder, plagued by a penchant for mishandling balls hit to him on the ground. And the derring-do of August 15 notwithstanding, Zinn had not developed into an effective base-stealer, being thrown out almost 40 percent of the time on theft attempts.26

Also undisclosed to outsiders but worst of all, Zinn proved a dissension-causing actor in the clubhouse. He became a card-playing companion of star first baseman and suspected game-fixer Hal Chase. As a subversive member of a bad ballclub headed for a last-place (50-102, .329) finish, Zinn rapidly fell into disfavor with Wolverton.27 An August batting slump then provided the Highlanders manager the cover needed to rid himself of this troublesome rookie.

Zinn’s offensive stats (6/55/.262 in 106 games) approximated the full-season batting averages of outfield teammates Roy Hartzell (1/38/.272) and Bert Daniels (2/41/.274), with considerably more power.28 Even so, Zinn was dispatched to the Rochester Hustlers of the International League in late August.29 Stunned and angry, he refused to accept the demotion and declined to report, saying that he “would rather retire than return to the minors.”30 As a result, New York was obliged to send recently acquired outfielder Klondike Smith to Rochester in his stead.31 Hustlers boss John Ganzel, meanwhile, placed the recalcitrant Zinn on the Rochester suspended list, where he spent the remainder of the 1912 season.32

After several months back in the workaday world, Zinn “reconsidered his determination to give up baseball and will report to the Hustlers next spring,” said Sporting Life.”33 But there was apparently a catch. Zinn would report to Rochester spring camp in 1913 — but only if reimbursed the month-plus wages that he had forfeited while on the club’s suspended list the previous season, an arrangement apparently agreed to by Hustlers boss Ganzel.34 Zinn repaid this largesse by sowing strife within the club, his late-night fistfight with first baseman Butch Schmidt bringing rumors of team dissension into the open.35 Still, Zinn put up solid numbers for Rochester. In 110 games, he batted .287 with 28 extra-base hits and earned himself another shot in the majors. In mid-August, Zinn’s contract was purchased by the National League Boston Braves.36

Zinn made a splash on reentry into the big time. In his first game for Boston, he went 3-for-5 with a triple, handled seven chances in center field flawlessly, and sparked his new club to a 7-6 victory over St. Louis. The “all around clever playing of Guy Zinn stood out most prominently,” wrote Boston scribe William B. Grimes.37 Although that kind of pace could not be maintained, Zinn played well for Boston. In 36 late-season contests for a weak-hitting fifth-place club (69-82, .457), Zinn batted .297, with 11 extra-base hits and 15 RBIs. He also played a respectable (.948 FA) center field. Yet as soon as the season was over, he was remanded to Rochester.38

For the local press, evidently unaware of the turmoil that Zinn caused in various clubhouses, his release was a head-scratcher. Nor was Boston management very forthcoming about the reasons behind Zinn’s termination. “Zinn came to the Braves from the Rochester club and in a few games shone brilliantly but, in the judgment of the Braves’ management, he was lacking in the qualities required for the 1914 season,” observed an unidentified Boston Herald sportswriter, leaving the vague club rationale for Zinn’s departure unexplained.39 A.H. Mitchell, Sporting Life’s Boston correspondent, openly expressed his puzzlement at the jettisoning of Zinn and first baseman Hap Myers, but hinted at something besides game performance being the cause of the moves: “Both are good men, almost first class and good judges here wondered that [Boston manager George] Stallings disposed of them. Doubtless there are reasons that do not appear on the surface. … Zinn looked very good to Boston fans. … He certainly looked better than some of the outfielders that Stallings retained. But as I said, there may be something under the surface in Zinn’s case. Doubtless, Stallings had good reason to send him back to Rochester.”40

Perhaps understandably, Rochester did not want Zinn back, his strong performance for the 1913 Hustlers notwithstanding. Claiming to be overstocked with outfielders, Rochester promptly put Zinn up for sale. And in December the Louisville Colonels of the American Association grabbed him.41 Now, W.M. Leahy was the Sporting Life correspondent whose commentary left unsaid why Rochester had let the productive outfielder go: “Guy Zinn has been sold again, this time to the Louisville club of the American Association. Zinn is a good ballplayer and a fairly good hitter, but as the local management had no use for him they decided to let him go. A change of scenery and climate may do him good.”42 But Zinn had ideas of his own and would not be heading for Louisville.

Trouble for baseball’s establishment was in the offing during the winter of 1913-1914. After having played a season as an unaffiliated minor-league circuit concentrated in the Midwest, the Federal League placed franchises in large Eastern venues like Brooklyn, Baltimore, and Buffalo and declared itself a major league. Disregarding Organized Baseball’s reserve clause, the Feds then began raiding National and American League rosters for playing talent. One of the first big leaguers signed by the Federal League was none other than Guy Zinn, inked to a contract by the fledgling Baltimore Terrapins.43 On April 13, 1914, municipal dignitaries and a paid crowd of 27,692 jammed Terrapins Field to witness Baltimore and Buffalo do battle in the inaugural game played by the Federal League as a major league. With the game scoreless in the bottom of the fourth, Zinn led off by slashing a double to right off Buffeds right-hander Earl Moore. One out later, Harry Swacina’s double to left drove in Zinn with the first run ever recorded in the third major circuit.44 The Terrapins eventually went on to win the game, 3-2, with local sportswriter Shear Matthews naming Zinn one of the game’s stars.45

As the campaign approached the halfway mark, Zinn had established himself as Baltimore’s everyday center fielder, playing competent defense and posting respectable batting numbers: .280 BA, with 19 extra-base hits and 25 RBIs. Then, calamity struck. During a Sunday July 12 exhibition game against a Washington, DC, semipro team, Zinn broke his left ankle sliding into third base. The injury was a severe one, and put him out for the rest of the season.46 Guy Zinn would never be the same player thereafter.

When he returned to the Terrapins the following spring, it was obvious that Zinn’s injury had not fully healed. His “ankle is not quite right,” observed sportswriter Matthews. “He limps while running but manages to get about.”47 To accommodate Zinn’s reduced outfield range, he was shifted to left field for the coming season. As it turned out, the year proved an unhappy one for both Zinn and the Baltimore Terrapins. Appearing in 102 games, Guy’s batting average fell off slightly to .269, with modest power (26 extra-base hits and 43 RBIs) and only two stolen bases. He was also a defensive liability. The Terrapins fared worse, spending the season in the FL’s nether regions.

Late in the season that ended in a dismal last-place finish (47-107, .305), the Baltimore brain trust began paring veteran players from the club roster. With two weeks left in the campaign, Zinn was unconditionally released, but without his final paycheck.48 That winter, he emulated Chief Bender and other similarly aggrieved Terrapins and sued the club for unpaid salary.49 Shortly thereafter, the financially strapped Federal League went out of business, bringing the five-season major-league career of Guy Zinn to a close. In 314 American, National, and Federal League games, he posted a Deadball Era-respectable .269 batting average, with 89 extra-base hits, 136 runs scored, and 139 RBIs. But his defensive play was mediocre at best, with a career .927 fielding average divided fairly equally across the three outfield positions.

As with other players who jumped to the Federal League in disregard of the reserve clause in their contracts, the rights to Zinn reverted to the Louisville Colonels.50 But he did not remain club property long, being sold to the Scranton (Pennsylvania) Miners of the Class B New York State League before the 1916 season began.51 Regarded as “one of the best outfielders” in the NYS League,52 he was reclaimed by Louisville but failed to impress during a brief stint with the Colonels (.221 BA in 21 games).53 A month later, Zinn was shipped to New Orleans for an audition with the Southern Association Pelicans.54 But after going 5-for-26, he was returned to Louisville. By mid-August, Zinn was back in the New York State League, this time as a member of the Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Barons. He finished the season with a .260 batting average for Scranton/Wilkes-Barre, combined.55 Over the ensuing winter, Louisville, which still held the rights to Zinn, sold his contract to the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Americans of the Class B Eastern League.56 Used in only 63 games, he batted .263 the following season.

Although he was no longer a major-league-caliber player, the manpower drain attending American involvement in World War I re-elevated Zinn to the Double-A International League in 1918.57 He lasted until mid-July with the Newark Bears, drawing his release after being arrested for assaulting an offensive game patron in Baltimore.58 Guy then played a handful of games for the IL Jersey City Skeeters.59 In 70 games combined, he batted an inoffensive .218.

Zinn concluded his professional career with four seasons in the Class B Michigan-Ontario League, posting career-high marks in batting average (.324) and slugging (.499) for the Hamilton (Ontario) Tigers in 1919. The following season, he hit .307, with 33 extra-base hits. After an unsuccessful bid for the vacated Hamilton manager’s post,60 Guy returned to the club in 1921 and was batting .268 in 51 games when traded to a league rival, the Saginaw (Michigan) Aces, in early July.61 A crippling foot injury, however, prevented Zinn from playing any further that year.62

Zinn began the 1922 season with yet another Michigan-Ontario League club, the Brantford (Ontario) Brants, but was traded to the league-leading Bay City (Michigan) Wolves in late May.63 He managed at least one appearance in Bay City livery, but “bad legs that refused to respond to treatment” soon prompted his release.64 In 20 games combined between the two clubs, he batted .298.65 The last discovered report pertaining to the playing career of Guy Zinn placed him with a semipro club in Morenci, Michigan.66 Thereafter, he receded into the anonymity of private life.

By the time Zinn left baseball, his life was much altered from when he had started playing professionally some 16 years earlier. Although shrouded by the passage of time, it appears that he and his wife had separated by 1918. Guy was then a resident of Baltimore while Ethel Zinn and children remained in West Virginia. Two years later, the census listed Ethel, with preteen children Guy A. and Jean, as members of her father’s household. She and Guy evidently divorced soon afterward.67

Not long after he left the game, Zinn relocated to Poughkeepsie, New York, a small city along the Hudson River about 60 miles north of Manhattan. There, he lived and worked quietly as a lather and plasterer for the next quarter-century. The 1928 Poughkeepsie city directory registered Guy and a second wife named Verna (about whom nothing was discovered) as local residents. Verna disappeared from available records thereafter, and the 1940 US Census listed Zinn as a widower.

In 1949 he was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer and went back home to West Virginia for his final days. On October 6, 1949, Guy Zinn died at the home of his brother and boyhood teammate Romeo in the Clarksburg suburb of Nutter Fort.68 He was 62. Following funeral services, his remains were interred in the Zinn family plot in Greenlawn Cemetery, Clarksburg.

Some years after the death of Guy Zinn, baseball historians began efforts to track him down. By 1965, however, the only survivor of his immediate family was daughter Jean Zinn Talley.69 She was raised by her mother in the household of grandfather Carter, left home to get married at age 14, and ended up living in Louisiana. As a result, Jean had had little contact with her father and mistakenly thought that Guy had died in 1948. She could provide little information about him off the top of her head when located by baseball researchers, but promised to make inquiries.70 Thereafter, Jean returned a completed player questionnaire that listed Guy Zinn’s ancestry as “German-Jew.” With the Zinn clan having Protestant roots that went back centuries, what possessed Jean to list her father as Jewish is a mystery. But that was all it took to stoke interest in this long ignored Deadball Era mediocrity.

With his daughter’s designation accepted uncritically, Guy Zinn, whose religious beliefs had never been mentioned during his playing days, entered the pantheon of Jewish major league ballplayers. Baseball authors focusing on Jews in baseball incorporated him into their work.71 Even Jewish historical societies embraced him.72 This, in turn, had dramatic effect on the value of a 1914 Guy Zinn Baltimore News schedule-back baseball card. Already a rare piece of baseball memorabilia, Zinn’s now-presumed Jewishness skyrocketed the card’s market value. In 2010 a collector named Dan McKee placed a $250,000 value on his Zinn card. Six years later, McKee put the card up for sale, reducing its asking price to a mere $125,000.73 Sale negotiations promptly ensued with Jeff Aeder, a well-heeled collector of baseball cards of Jewish players. According to Aeder, Zinn’s religion was the key. “If Zinn was not a Jewish player, this card is probably a $10,000 card,” he told the New York Times.74

With his daughter’s designation accepted uncritically, Guy Zinn, whose religious beliefs had never been mentioned during his playing days, entered the pantheon of Jewish major league ballplayers. Baseball authors focusing on Jews in baseball incorporated him into their work.71 Even Jewish historical societies embraced him.72 This, in turn, had dramatic effect on the value of a 1914 Guy Zinn Baltimore News schedule-back baseball card. Already a rare piece of baseball memorabilia, Zinn’s now-presumed Jewishness skyrocketed the card’s market value. In 2010 a collector named Dan McKee placed a $250,000 value on his Zinn card. Six years later, McKee put the card up for sale, reducing its asking price to a mere $125,000.73 Sale negotiations promptly ensued with Jeff Aeder, a well-heeled collector of baseball cards of Jewish players. According to Aeder, Zinn’s religion was the key. “If Zinn was not a Jewish player, this card is probably a $10,000 card,” he told the New York Times.74

Aeder’s initial lowball offer of $10,000 immediately antagonized McKee. Sale negotiations then turned acrimonious following a poor rating given the card’s condition by the Sportscard Guaranty Company.75 In the end, the sale foundered and McKee kept the card. But press attention given the aborted baseball card deal extended all the way to Israel.76 The Zinn card dispute also engaged the interest of Bob Wechsler, an expert on Jewish baseball cards who promptly initiated his own inquiry into the matter. From the outset, Wechsler was struck by the fact that a Zinn family member-historian seemed perplexed by the claim that distant cousin Guy Zinn was Jewish, as the Zinns were a devoutly Christian family. He then discovered that a genealogist named Elaine Hirschberg had done extensive research on the Zinn clan, tracing them back to immigrant Seventh Day Baptists who had settled in the Virginias in the 1740s. The clincher was the discovery that author and encyclopedia designation of Guy Zinn as Jewish rested entirely upon the posthumous player questionnaire completed by ill-informed daughter Jean Zinn Talley. No independent or corroborative research of Zinn’s religious ties had been undertaken. That was enough for the Jewish Baseball Museum. Guy Zinn was struck from the rolls.77

Stripped of its religious cachet, the Zinn baseball card has plummeted in value. An older catalog listed an $8,800 quote; given its rarity and the passage of time since then, the card’s value now probably approximates the $10,000 value assigned to it by Jeff Aeder if its subject had not been a Jewish player.78 While $10,000 is hardly a trifling sum to the noncollector, it represents a more than 90 percent drop in the $125,000 price that Dan McKee placed on the Zinn card and that Aeder was seemingly prepared to pay for it (if ultimately necessary) in 2016.

From the Pioneer Era (Lipman Pike) through the 1930s (Hank Greenberg and others), the press invariably noted the arrival on scene of the relatively rare Jewish major-league ballplayers. Thus, the absence of contemporaneous reportage on Guy Zinn’s purported Jewishness should have placed baseball authors and encyclopedists on their guard. But it did not. Nor did the 1965 burial of brother Romeo Zinn in a Seventh Day Baptist Cemetery in Lost Creek, West Virginia. As a result, for several decades Zinn was accorded a distinction that was spurious. Not that it much concerned the man himself. Guy Zinn remained long dead throughout the entire kerfuffle.

Acknowledgments

A non-annotated version of this profile originally appeared in The Inside Game, Vol. XX, No. 4, October 2020. This version was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information recited above include the Guy Zinn file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; government records and Zinn family posts accessed via Ancstry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the notes. The piece also benefited from information about the Zinn family and the greater Clarksburg area kindly provided the writer by David Houchin of the Clarksburg-Harrison Public Library and Jessica Eichlin of the West Virginia and Regional History Center, and from the expertise of baseball card aficionado and SABR colleague Jeff Katz. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 An unincorporated community, Holbrook had a population of 139 according to the 1890 Census. See “New Birth Information Discovered,” SABR Biographical Research Committee Report, July 1997, 1.

2 The other Zinn children were Edwin Romeo (born 1886), Archie (1889), Percy (1892), Harry (1894), Noah (1896), Carl (1899), and Willa May (1901).

3 Per Bob Wechsler, “The Story of Why Guy Zinn, the Subject of a Famous Baseball Card, Is No Longer Considered Jewish,” jewishbaseballmuseum.com, posted January 12, 2017, citing the research findings of genealogist Elaine Hirschberg.

4 Zinn was also a pool hall and bowling alley hustler, often winning cash or prizes at small tournaments. See e.g., “Zinn Wins Gold Piece,” Clarksburg Telegram, December 2, 1907: 4, and “Winners at American Alleys,” Clarksburg Telegram, December 16, 1907: 4. Later, he fared less well against teammates in big city Baltimore. See e.g., “Runt Walsh Beats Zinn,” Baltimore Sun, December 22, 1914: 9.

5 In a 1914 questionnaire that he completed upon signing with the Federal League, Zinn listed himself as 5feet-11, 185 pounds.

6 See e.g., “Clarksburg Won from Zanesville,” Clarksburg (West Virginia) Telegram, May 7, 1906: 7. Romeo Zinn was a pitcher-third baseman on the Clarksburg team.

7 See “The Reds Won Only by Effort,” Clarksburg Telegram, August 15, 1906: 4, for an extensive account of the game. The box score was published in the Cincinnati Post, August 15, 1906: 6.

8 As subsequently noted in “Zinn with Them,” Clarksburg Telegram, April 20, 1908: 4. Baseball-Reference and other authority take no notice of Zinn’s professional experience during the 1907-1908 seasons, starting his stats with the Grafton club in the Pennsylvania-West Virginia League of 1909.

9 See “Clarksburg Americans,” Clarksburg Telegram, June 17, 1907: 3.

10 See again, “Zinn with Them,” Clarksburg Telegram, April 20, 1908: 4.

11 Per “Bits of Baseball Gossip,” Clarksburg Telegram, May 12, 1908: 4.

12 “Goes South,” Fairmount (West Virginia) West Virginian, September 25, 1909: 5.

13 “Zinn Goes South,” Washington Times, September 27, 1909: 11.

14 Per “Goes South,” Fairmount West Virginian, September 25, 1909: 5. See also, “Players Who Are Drafted,” Charleston (South Carolina) Evening Post, September 23, 1909: 3.

15 As reported in “Rain Stops Game in Macon,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, August 11, 1910: 4; “American Association Gets Zinn,” Fairmount West Virginian, August 18, 1910: 6; “Condensed Dispatches,” Sporting Life, August 20, 1910: 6. Armour had tried to draft Zinn the year before “but lost him to Memphis on a fluke,” according to “Brief Review of the Week,” Sporting Life, August 27, 1910: 15.

16 See “American Association Bulletin,” Washington Evening Star, November 27, 1910: 58; “The Tri-State League,” Sporting Life, December 10, 1910: 3.

17 As reported in “New York Pays $1,000 for Zinn,” Wilmington (Delaware) Evening Journal, August 17, 1911: 4; “Altoona Sells Zinn,” Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Gazette and Bulletin, August 18, 1911: 1; and elsewhere. During its early years, the American League Ball Club of Greater New York did not have an official nickname but was commonly known as the Highlanders during the decade (1903-1912) that home games were played at Hilltop Park in far north Manhattan. By 1904, however, the more headline-friendly Yanks or Yankees was also being used, and that usage became universal after the club became tenants of the New York Giants at the nearby Polo Grounds in 1913.

18 As reported in the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Evening Farmer, Jersey (Jersey City) Journal, and elsewhere, September 1, 1911.

19 Per “Major League Players,” Sporting Life, November 11, 1911: 8.

20 W.J. Macbeth, “New York Has a Chance to Get Both Big League Flags,” Denver Post, April 21, 1912: 29.

21 According to a widely published wire dispatch. See e.g., “Tinker and Carey Are Timely Hitters,” Seattle Times, August 18, 1912: 27; “Joe Tinker Heads the Pinch Hitters,” Ogden (Utah) Evening Standard, August 23, 1912: 10.

22 Both thefts came as part of a successfully executed double steal.

23 Washington Bee, July 20, 1912: 2.

24 “Makes Good as Regular,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 2, 1912: 15C.

25 (WaKeeney) Western Kansas World, July 20, 1912: 7.

26 Zinn’s 17 steals in 28 attempts yields a 39.3 percent failure rate.

27 An unflattering anecdote about Zinn and Chase is provided by authors Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella in The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game (Toronto: Sports Classic Books, 2004), 163-164.

28 The fortunes of the 1912 New York Highlanders were crippled by the unavailability of outfield regulars Birdie Cree and Harry Wolter, sidelined by injuries for most of the season.

29 As reported in “Highlander Released,” Boston Herald, August 24, 1912: 8: “Highlanders Release Zinn,” Trenton Evening Times, August 24, 1912: 7; and elsewhere. In return, Rochester sent former Washington Senators first baseman-outfielder Jack Lelivelt and an unspecified amount of cash to New York

30 Per “No Minor Leagues for Zinn,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, August 29, 1912: 11. See also, “Zinn Refuses to Play for Rochester,” New York Times, August 29, 1912: 7, and “Zinn Refuses to Go to Rochester,” Pawtucket (Rhode Island) Times, August 29, 1912: 2.

31 See “Zinn Refuses to Play with Rochester,” Washington Times, August 29, 1912: 12: “Zinn Says He’s a Major Leaguer and Refuses to Join Rochester Team,” New York Sun, September 1, 1912: 16.

32 Per “Zinn Under Suspension,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 30, 1912: 7; Harry Dixon Cole, “New York Nuggets,” Sporting Life, September 7, 1912: 4.

33 “News Notes,” Sporting Life, November 30, 1912: 11.

34 See “Guy Zinn Reports at Rochester Camp,” Jersey Journal, April 4, 1913: 15.

35 Per “Trouble Reported in Hustlers’ Camp; Players in Fight,” Providence Evening Bulletin, July 3, 1913: 14.

36 As reported in “Doves Get Zinn from Rochester,” Jersey Journal, August 19, 1913: 7; “Ex-Yankee Goes to Braves,” Washington Evening Star, August 19, 1913: 13; and elsewhere.

37 William B. Grimes, “Braves in Their Might Crumble Cards,” Boston Herald, August 22, 1913: 6.

38 See “Four Braves Are Released,” Boston Herald, October 9, 1913: 9.

39 “Four Braves Are Released.”

40 A.H. Mitchell, “Boston Budget,” Sporting Life, October 18, 1913: 2.

41 As reported in a widely disseminated International News Service dispatch. See e.g., Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, December 10, 1913: 12; Denver Post, December 11, 1913: 11; and El Paso Post-Herald, December 13, 1913: 36.

42 W.M. Leahy, “International League,” Sporting Life, December 23, 1913: 6.

43 See “Terps Sign Three Men,” Baltimore Sun, January 14, 1915: 5; “Knabe Gets Three Players to Jump,” Newark Evening Star, January 15, 1914: 18; “Baltimore Gets Three Big Leaguers,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, January 16, 1914: 1. The other two Baltimore signees were current Brooklyn infielder Enos Kirkpatrick and one-time Chicago White Sox pitcher Frank Smith.

44 For an inning-by-inning account of game action, see “Great Crowd Sees Feds Start Season,” Chicago Daily News, April 13, 1914: 1. See also, “Third League Starts,” Sporting Life, April 14, 1914: 1.

45 See C. Shear Matthews, “Glorious Inaugural for Terrapins,” Baltimore Sun, April 14, 1914: 1.

46 As reported in “Zinn Breaks Leg Sliding,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, July 13, 1914: 6: “Zinn Breaks Leg with Semi-Pro Team,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 13, 1914: 10; and elsewhere.

47 C. Shear Matthews, “Fans Await Gong for Fed Opening,” Baltimore Sun, April 10, 1915: 6.

48 As revealed in “Wild Heave Loses Game,” Baltimore Sun, September 18, 1915: 3. See also, Emmanuel Daniel, “Baltimore Budget,” Sporting Life, September 25, 1915: 2.

49 See “Zinn Enters Suit Against the Terrapins,” Baltimore Sun, December 21, 1915: 2. As their enterprise headed toward financial collapse, a number of Federal League clubs repudiated the contracts signed with players. See generally, Joe Vila, “Paid Their Bill to Players,” Sporting Life, November 13, 1915: 8. The outcome of the Zinn suit, however, was not discovered by the writer.

50 Per Sporting Life, November 16, 1915: 14.

51 See “Secretary Farrell’s Bulletin (of March 15, 1916),” Sporting Life, April 15, 1916: 16.

52 Harrisburg Patriot, July 4, 1916: 8.

53 Louisville retrieved Zinn when Scranton reneged on full payment of the purchase price. See “Manager Lewis Lands Two Clever Players,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times, August 14, 1916: 6.

54 Per “George B. Barrett’s Louisville Lines,” Sporting Life, August 12, 1916: 10.

55 Per the 1917 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 160.

56 As reported in “Manager Krichell Expects Guy Zinn to Be Cleanup Batter for Bridgeport Club,” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, February 19, 1917: 11.

57 Zinn, married with two young children, was not a likely target for military conscription.

58 See “Newark Wins One Game: Loses Second,” New York Sun, July 14, 1918: 69.

59 The International League was the only minor-league circuit to complete its schedule, ending play on September 2, 1918.

60 As noted in “Brief Bits of Sport,” Twin Falls (Idaho) News, February 12, 1921: 7.

61 Per “Zinn and Brooks to Wear Ace Unis,” Saginaw (Michigan) News, July 5, 1921: 10.

62 As subsequently revealed in “Clements, Byrne Are Keeping Busy,” Saginaw News, January 18, 1922: 1

63 As reported in “Bay City Secures Pierce from Browns,” Ann Arbor (Michigan) News, May 26, 1922: 12; “Two New Players,” Flint (Michigan) Journal, May 26, 1922: 30; and elsewhere.

64 “Zinn Is Released,” Adrian (Michigan) Telegram, June 7, 1922: 7, and Flint Journal, June 7, 1922: 16.

65 According to a detailed log of his career of unknown origin contained in the Guy Zinn file at the Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown. Baseball-Reference end’s Zinn’s professional playing career the previous season.

66 As reflected in the box score accompanying “Adrian Wins Again Over Morenci, 2-0,” Adrian Telegram, July 17, 1922: 7.

67 Guy did not reside with the Carter family, but his whereabouts in 1920 were undiscovered by the writer. By 1930, Ethel Zinn is employed as a West Virginia prison matron and divorced. Guy, meanwhile, is listed as a lather working in Poughkeepsie and married, presumably to second wife Verna.

68 According to his death certificate and official West Virginia death records. In actuality, Zinn likely died three days earlier, as his death was reported in various news outlets on October 4, 1949. See e.g., Clarksburg Telegram, October 4, 1949, and Associated Press carriers like the Canton (Ohio) Repository, Hagerstown (Maryland) Morning Herald, and Washington Evening Star, October 4, 1949. Same gave the date of Zinn’s death as October 3, as did The Sporting News in its October 12, 1949, edition.

69 Son Guy A. Zinn died in 1936 and first wife Ethel in 1945.

70 Per correspondence and memoranda in the Guy Zinn file at the GRC.

71 See e.g., Peter S. Horvitz and Joachim Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball (New York: S.P.I Books, 2001), and Burton A. Boxerman and Benita W. Boxerman, Jews and Baseball, Volume I: Entering the American Mainstream, 1871-1948 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2006). Among other things, Guy Zinn now became the only Jew to play in the Federal League.

72 See e.g., “No. 21, Guy Zinn,” American Jewish Cultural Society, 2003.

73 See “Jewish Player Guy Zinn’s 100 Year Old Baseball Card Worth $125,000,” Jewish Business News, December 19, 2016.

74 Per Ben Berkon, “A Jewish Player’s 1914 Baseball Card Triggers a $125,000 Dispute,” New York Times, December 19, 2016: D5. Aeder later explained his undisclosed willingness to pay the $125,000 asking price thusly: “It really is something that if you have the means and the obsession, then someone pays a lot more than it’s worth,” per Brandon Chiat, “Local Baseball Card Collector Holds All the Cards,” JMUKT: Baltimore Jewish Living, March 2, 2017.

75 Because of chipping along the margins, a crease, and paper loss on the back, the 1914 Zinn card was given a 1, the lowest possible rating for condition.

76 See Gabe Foreman, “A 1914 Jewish Baseball Card Sparks a $125,000 Fight,” The Times of Israel (Jerusalem), December 20, 1916.

77 See again, Wechsler, above. Apparently undiscovered during the Wechsler inquiry but further undermining the notion that Guy Zinn was Jewish is the final resting place of brother Romeo Zinn in Seventh Day Baptist Cemetery in Lost Creek, West Virginia.

78 Per email of baseball card aficionado Jeff Katz to the writer, July 25, 2020.

Full Name

Guy Zinn

Born

February 13, 1887 at Holbrook, WV (USA)

Died

October 6, 1949 at Park, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.