Bill Traffley

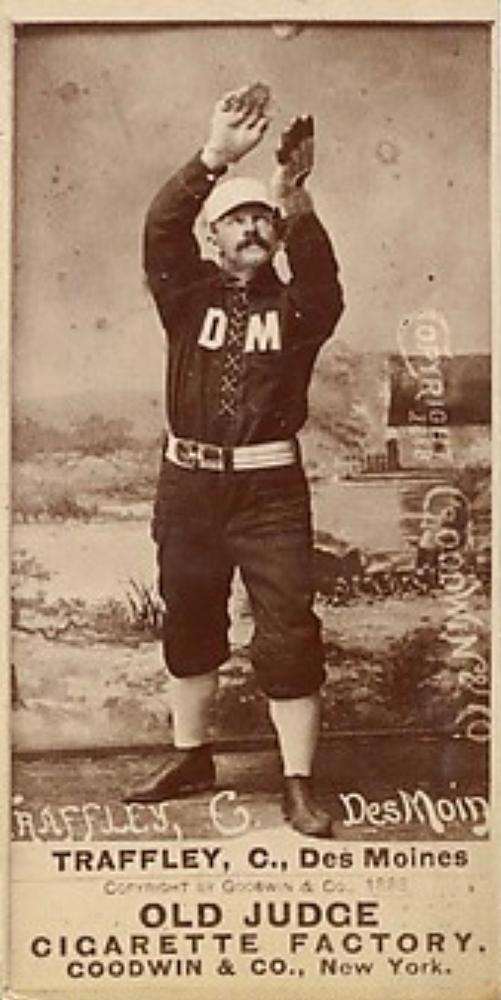

When rule changes in the 1880s allowed pitchers to begin throwing overhand, and therefore much faster, a skilled catcher was a valuable commodity. The following summed up how Bill Traffley was viewed: “The one thing that makes Traffley a very desirable catcher is his indomitable will, his energy, and the desperate chances which he accepts. He goes after every ball and gets many at critical times which turns the tide of defeat into success.”1 In the time of small roster sizes, a catcher who could also play other positions – in Traffley’s case, the odd combination of catcher and shortstop – made him even more valuable. So, despite a career major-league batting average of just .175, Bill Traffley played in parts of five seasons in the National League and American Association.

When rule changes in the 1880s allowed pitchers to begin throwing overhand, and therefore much faster, a skilled catcher was a valuable commodity. The following summed up how Bill Traffley was viewed: “The one thing that makes Traffley a very desirable catcher is his indomitable will, his energy, and the desperate chances which he accepts. He goes after every ball and gets many at critical times which turns the tide of defeat into success.”1 In the time of small roster sizes, a catcher who could also play other positions – in Traffley’s case, the odd combination of catcher and shortstop – made him even more valuable. So, despite a career major-league batting average of just .175, Bill Traffley played in parts of five seasons in the National League and American Association.

William Franklin Traffley was born December 21, 1859, in Staten Island, New York. No birth record was found, nor were there listings of a William, Bill, or Wm. Traffley in 1860 or 1870 census records. However, a couple of clues may shed some light on his ancestry and childhood. A younger brother, John Traffley, played one game for Louisville of the American Association in 1889 (more on him later). John is shown born in Chicago in 1862.2 This means that sometime between William’s birth in 1859 and John’s, the family moved to Chicago. In addition, a Henry Traffley, born in New York, is listed on Chicago voter registration rolls in 1888, 1890, and 1892.

John Traffley’s Find-a-Grave entry in Ancestry.com pulls up two other “suggested records,” one for his U.S. Professional Baseball Player Profile and another for an 1870 U.S. Census record for a family named Trefflich living in Chicago. This family was headed by father August and mother Katherina. It included children Henry, age 16; Willie, age 14; Fred, age 11; John, age 9; and a younger sister, Marie. If it is assumed Willie Trefflich was William Traffley (the year of birth and age differ by a couple of years), this entry matches younger brother John and presumably an older brother Henry. Although not conclusive, this is the best evidence available as to Bill Traffley’s origins.

By 1878 Traffley was playing for a team in Chicago called the Crooks, described as a “North Side amateur organization.” The account mentioned that he had also at one time “played with the Peoria Reds.”3 Another source said that as a teenager he worked in a rolling mill and played for a “corner lot” team called the Onwards.4 The 5-foot-11, 185-pound, right-handed Traffley was primarily a catcher, but he also played shortstop and several other positions.

The White Stockings came to sign him, though it is not known exactly how. By one account, Cap Anson once saw Traffley play, was impressed with his speed and arm, and invited him in for a tryout. White Stockings manager Bob Ferguson was also impressed with the young catcher and signed him to a contract.5 Another theory put forward, based on memories of a friend several decades later, was that one day “Silver Vance (he probably meant Silver Flint) was the catcher. ‘Silver’ was taken down sick and [A. G.] Spalding …sent for ‘Billy’ to take his place. And he did too. Not a ball got past him and from then on, his reputation as a ballplayer was established.”6 The only problem with this story was that Flint was with Indianapolis in 1878 and didn’t join the White Stockings until the following season.

Regardless, the 18-year-old Traffley was signed and made his major-league debut on July 27, 1878, against the Indianapolis Blues at Lake Front Park in Chicago. His opportunity came because the White Stockings’ regular catcher, Bill Harbridge, “was so lame that he could not play that day.”7 Facing the Blues’ starting pitcher, The Only Nolan, Traffley had one hit in four at-bats. However, his two passed balls in the first inning led to two Indianapolis runs,8 which was one reason given for the 4-3 Chicago loss.9 Nonetheless, the review of his performance was generally positive. “The catching of Traffley was excellent after the first inning. His throwing to second was a model for any catcher to imitate … But after all, Traffley needs practice to handle Terry] Larkin’s delivery.”10

His next game, two days later, also against Indianapolis, didn’t go as well. Although the White Stockings won 12-9, Traffley went 0-for-5, was charged with eight passed balls, and the local press was less kind in its critique. “The game, if lost, would have been entirely chargeable to Traffley. There seems to be some fatality about the young man’s catching, in that he cannot hold a ball the third time the batter strikes at it … [Traffley] is a good boy, and plays well enough for an exhibition game, but has no business in front of Larkin in a league contest.”11

The Chicago Tribune story was a little more forgiving, saying, “Traffley was all abroard (sic) for the first four innings, during which he seemed entirely unable to hold the pitching even fairly well. After that he braced up and played the last five innings without an error. He will need a good deal of practice before he can get the hang of such a delivery as Larkin’s.”12

Traffley was taken on the club’s Eastern road trip, where he would catch in non-league games.13 The only appearance found was against Buffalo of the International Association in early August, when he went 1-for-5 against Pud Galvin and Bill McGunnigle. It is not known how long Traffley remained with the White Stockings after that.

Early in 1879 Traffley signed with the Omaha Greenstockings of the Northwestern League. No reports of him playing ball in 1880 could be found, but a “Mr. Traffley” was credited with putting out a fire that broke out in a newspaper office in Omaha in June of that year,14 so it’s likely that he was in town. He was still in Omaha in 1881, by then playing for the semipro Union Pacific Railroad team. The team took a road trip to Colorado and Traffley may have stayed behind, because he was listed as a member of the Denver and Rio Grande Club of Colorado Springs in the fall of 1881.15 He was still playing in Colorado Springs (the team changed their name to the Colorado Reds) early in 1882.16 After that, he returned to Omaha and the Union Pacific club.

Traffley was said to have made “quite a reputation”17 and to be “in big demand.”18 Thus, he got a chance to return to the major leagues when he was signed by the Cincinnati Red Stockings of the American Association on May 3, 1883. Initially his acquisition was merely as insurance in case of injury (which was common among catchers of the era) to player-manager Pop Snyder or his backup, Phil Powers.19 However, Traffley did get into 30 games (the team played just 98, going 61-37, good for third place in the league). He was used mostly as Ren Deagle’s personal catcher.

Traffley batted an even .200 but was said to excel on defense. One report late in the season stated, “Traffley, catcher of the Cincinnati team, plays a beautiful game behind the bat. Some of his stops are wonderful, and his throwing to second is so swift and accurate that it generally costs the life of the stranger who attempts the larceny of that covetous spot.”20 His fielding statistics, however, tell a different story. In 29 games as catcher, Traffley was charged with 36 passed balls and committed 27 errors for a woeful .851 fielding average.

In late August 1883, Secretary Claytor of the Cincinnati club approached Traffley and teammates Joe Sommer and Phil Powers with a proposition. They could sign an “agreement to remain” and were promised a $1,300 salary for 1884 – but if they refused, they would be reserved at a salary of $1,000.21 Faced with this decision, all three players signed the agreement and Cincinnati did not place them on their reserve list. When this became known after the October 10 deadline had passed, Baltimore manager Billy Barnie acted quickly and signed Traffley and Sommer, along with another Red Stocking not reserved, Jimmy Macullar. Cincinnati officials threatened the players with expulsion but after a meeting between management and the players, the Red Stockings withdrew their charges. As a result, Traffley became a member of the Baltimore Orioles.22

Traffley was the backup to Sam Trott with the Orioles in 1884, usually catching future major-league umpire Bob Emslie whereas Trott was behind the plate for most of Hardie Henderson’s starts. Traffley played in 53 games, 47 at catcher, and hit .176. He also continued to struggle behind the plate, allowing 65 passed balls and being charged with 30 errors. The Orioles finished 20 games over .500 (63-43-2), but that was good for only sixth place in the American Association, 11½ games behind the league-leading New York Metropolitans.

Traffley’s record shows one game as an umpire in 1884. The regular umpire, Billy Quinn, failed to show for a late September game against the Alleghenys in Pittsburgh and Baltimore manager Barnie was called into service. After taking much abuse in response to calls favoring his team, Barnie retired in the third inning and was replaced by Traffley, who was not playing that day. He did better but after an unpopular call in the eighth inning, “the left field crowd broke in a body into the field and advanced threateningly on the umpire.” Police pushed the crowd back, but they kept up their verbal abuse of Traffley until he declared a 9-0 forfeit win for the Orioles. At that point, “The Baltimores took Traffley carefully into their protective wing, and the whole Baltimore delegation was escorted out of the grounds to their omnibus with a yelling, abusive crowd of disgusted spectators in the rear.”23

Traffley became a starter for the Orioles in 1885, catching in 61 of the team’s 110 games. Again, he hit poorly (.154 batting average) and behind the plate he achieved the odd combination of leading American Association catchers in fielding percentage (.943) while allowing 104 passed balls, a total that is tied for third place for the most in major-league history. He was reserved by Baltimore for 1886 but apparently his defense had not improved. A report from a July game said that “Traffley’s catching was wretched.”24 He didn’t hit much either, batting .212 in 25 games before being released in late July. This concluded Traffley’s big-league career. In parts of five seasons with Chicago in the National League (1878) and Cincinnati and Baltimore of the American Association, he had a career batting average of .175 in 179 games.

After his release by Baltimore, he briefly hooked on with the Duluth (Minnesota) Jayhawks of the Northwestern League. That fall Traffley was signed by the Toronto Canucks of the International Association.25 After one year in Canada Traffley signed with the Des Moines Prohibitionists of the new Class A Western Association. (The Northwestern League, where Traffley played in 1886, was reorganized as the Western Association beginning with the 1888 season). He could not hit pitching in the minors much better than he did at the top level, batting .197 in 68 games. He improved slightly to .216 in 101 games in 1889. Traffley returned to Des Moines in 1890 (the team transferred to Lincoln, Nebraska, that August).

Another event in 1889 involved Bill’s brother John. In the middle of June, the Louisville Colonels of the American Association were in the midst of a 26-game losing streak. Team owner Mordecai Davidson began levying fines on players for poor play. When he refused to rescind the fines, several players went on strike. Six players refused to take the field for a June 15 game against Baltimore, so the Colonels filed their lineup with local amateurs.26 One of them was John Traffley, who batted ninth, played right field, and went 1-for-2 in his only major-league game. Why he happened to be in Louisville and why he was selected to play are both unknown.

Despite his poor offensive contributions, Bill Traffley’s three seasons in Des Moines were not without excitement. After a game in June 1889 in Sioux City, he, manager Jimmy Macullar (his old teammate in Cincinnati), and several other Des Moines players visited an establishment “where beer flows in spite of prohibition.”27 After getting sufficiently under the influence, Traffley and Macullar sought out an umpire named Clarke at his hotel to confront him about some unfavorable decisions during that afternoon’s game. Traffley and Macullar then “brutally beat and kicked him.”28 As a result, “[Clarke] emerged with blackened optics and a generally demoralized appearance.”29 Both players were arrested and at first it was thought that they would be expelled, but a hearing was held the next day. Macular was fined $10 and costs, and Traffley $25 and costs, “all of which was paid.”30

Traffley signed with Lincoln for 1891 but played in just five games.31 After he had a run-in with manager Dave Rowe, he asked for and was given his release. Apparently, he wasn’t getting much playing time early in the season, so in a game in Milwaukee Rowe ordered him to man one of the gates. When Traffley objected, Rowe said, “God d—n you, ain’t you gettin’ your salary?” Traffley replied, “The salary is all right, but I want a chance to play ball occasionally or I want my release.”32 He then joined Omaha, also in the Western Association. In July, the Omaha club disbanded, but Traffley remained in town and rejoined the team when it wase reorganized as an independent club a couple of weeks later.

There were rumors that Traffley would play on the West Coast in 1892, but instead he signed on with the Deadwood (South Dakota) Metropolitans of the independent Black Hills League and was named the team’s manager. It was implied that Traffley planned to retire from baseball and settle in Deadwood. “Mr. Traffley wishes to leave the profession and comes to Deadwood to make this his home and grow up with the country …[he] will not follow ball playing as a business if he can get employment that will pay him as well here.”33

However, misfortune followed Traffley to Deadwood and his plans changed. That summer a drunken stranger attempted to sexually assault Traffley’s five-year old daughter. When Traffley later located the man, he “knocked him down, hammered his face to a pulp and then raised him above his head and dashed him repeatedly head foremost to the sidewalk.”34 He spent the winter in Deadwood, where he set up a “liquid refreshment business.”35 However, a fire destroyed his business and the home he and his family occupied, so he left town.

There were reports that Traffley tried to organize clubs in both Ogden, Utah,36 and Salem, Oregon,37 that spring. He did play a few games for Kansas City of the Western Association in May and June, but by mid-June he was back in Deadwood, where he apparently remained the rest of the year. In the spring of 1894 Traffley returned to Des Moines (where he’d played five years earlier) when he was signed as player-manager. He had lost none of his combative nature. In a game against Rock Island in August he went into the stands and administered a “thrashing” to a fan who insulted his wife. The report noted, “Traffley was warmly applauded.”38

Traffley returned to Des Moines in 1895. Sharing catching duties with Herm McFarland and filling in at shortstop, Traffley batted .263 and led the team to a third-place finish in the league. He spent the off-season upgrading the Prohibitionists’ roster (other league managers accused him of exceeding the salary limit), and in 1896 Des Moines got out of the gate with a 26-2 start, including a 25-game winning streak. The ace of the staff was Frank Figgemeier, who won 13 straight decisions during the streak. By mid-June, the club’s dominance had the effect of reducing fan support in league cities, including Des Moines, resulting in reduced revenues.

Western Association officials met in Des Moines in early July and, in an effort to reduce costs, dropped the team salary limit from $1,400 to $900 per month.39 Des Moines was reportedly paying out $400 more than any other team (Dubuque was the only other team exceeding $900 at the time).40 At first Traffley threatened to move the team, but the only alternative left to him was to sell his best players for what he could get, before getting only $250 for those who were drafted by a major league club after the season.41 Using cheaper replacement players, the Prohibitionists cooled off but still finished in first place with a 56-22 record. The league disbanded on August 1 and Traffley resigned his position.

Traffley also figured in the evolution of groundskeeping. Among the innovators was August Solari, who purchased land and constructed ball grounds that later became known as Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. When he later was employed as superintendent and groundskeeper at the park in the 1880s, he was credited with being one of the first to use field coverings, first only on the base paths but later the base areas and batter and pitcher’s box, to keep the field dry and playable in case of rain. A few years later, Abner Powell, a manager in New Orleans, was the first to use a one-piece canvas to cover the entire infield.42 The practice did not come into widespread use, at least in the major leagues, until much later. Fred Clarke, a manager for the Pittsburgh Pirates was awarded a patent for a “Diamond Cover” in 1911.43 Also in 1911, a man named William McDonald, also of Pittsburgh, was issued a patent for a “diamond cover for base ball fields.”44

Yet Traffley may have come up with the idea much earlier. Several Midwestern newspapers ran the following item in December 1896. “Manager Traffley has been for some time figuring on some plan so the diamond can be kept dry in case of rains at night or in the forenoons of days on which games are scheduled. [His] plan is to have an oiled canvas 150 feet square, which will be large enough to cover the diamond, keeping it dry back to the grand stand. The canvas will be high enough in the center of the diamond to throw the water off into the field and will be so arranged that it can be placed in position in five minutes. The expense will be about $150. This amount, Mr. Traffley says, a club could make up on one Sunday game if the weather should clear up two or three hours before the time to call the game. He says he will apply for a patent on his invention.”45

When the Quincy (Illinois) Little Giants were granted a franchise in the 1897 Western Association, Traffley was hired as player-manager. He resigned in July but stayed on as a catcher after he was offered, but declined, a job as umpire in the Western Association. After the season he tried to organize an independent team in Quincy “on the co-operative plan…by which each player becomes a stockholder and equally interested financially.”46 That effort failed, but he took the concept east when he was signed to manage the Hartford (Connecticut) Cooperatives in the Atlantic League in 1898. By then he was pushing 40 years old and often being referred to as “Dad” Traffley. This was his last season as an active player.

According to the 1900 U. S. Census, Traffley had been married for 14 years, meaning that sometime around 1886 he married Ella P. Groom. She was a native of Maryland, so the marriage probably took place while he was playing in Baltimore. The couple had five children: three daughters (Ella, Nettie, and Lillian) and two sons (William, Jr. and Harold). William Jr. died in January 1913 at the age of 16 from an undisclosed “one-year illness.”47 The birthplaces of Traffley’s children reflect the different stops during his more than 20-year career in baseball. Ella was born in Maryland, Nettie in Iowa, Lillian in South Dakota, William in Illinois, and Harold in Iowa.

Traffley appears to have had an earlier marriage: a record shows William Traffly (without the “e” in his name) marrying Lizzie Heller in Chicago on June 4, 1878. This union produced another child. There is an 1880 U.S. Census record for a Wm. Traffley living in Omaha with an occupation of “worker in a foundry.” The entry shows him married to Eliza and with an infant son, Chas. H. An obituary and death notice were found for Elizabeth E. Traffley, age 27, “beloved wife of William Traffley,” who died in Baltimore (where Bill was playing at the time) in 1885.48 Her early death might be explained by a story after Traffley’s death more than 20 years later. A childhood friend said, “Billy used to have lots of money but he spent it all on his first wife who was an invalid.”49 It’s not known who raised his child but Charles Henry Traffley lived until 1943.

After his one season in Hartford, Traffley returned to his home in Des Moines, where he remained involved with area semipro teams and tried to organize a league in central Iowa in 1905. At some point he contracted tuberculosis; Bill Traffley died on June 23, 1908, at the age of 48. He was survived by his wife Ella and their three children. He was buried at Woodland Cemetery in Des Moines, and his obituary provided the following fitting epitaph: “Traffley will be recalled by the older fans in Omaha as a splendid catcher, a quiet and persistent worker and a man whom it was a pleasure to know, either on or off the diamond.”50

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, statistics from Traffley’s playing career are taken from Baseball-Reference.com; genealogical and family history was obtained from Ancestry.com.

The author also used information from Traffley’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 “One of the First to Sign,” Lincoln (Nebraska) State Journal, February 10, 1891: 5.

2 Some sources indicate John Traffley may have been born in 1863.

3 “Sporting,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1878: 7.

4 “Boyhood Friend Tells of Traffley,” Des Moines Register, Jun 25, 1908: 10. Information in this article came some 30 years after the incident and was reported after Traffley’s death. The source was an interview with a boyhood friend of Traffley’s named John Ullrich, described as a “turnkey at the city jail.”

5 Al Pepper, Mendoza’s Heroes, Clifton, Virginia: Pocol Press (2002): 36.

6 “Boyhood Friend Tells of Traffley.”

7 “Sporting Gossip,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, July 29, 1878: 2.

8 “Sporting,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1878: 7.

9 “Sporting Gossip,”

10 “Sporting,”

11 “Sporting News,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, July 30, 1878: 5.

12 “Sporting Events,” Chicago Tribune, July 30, 1878: 8.

13 National League teams often played against minor league, semipro, or amateur teams on off-days in the schedule.

14 “State News,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Globe, June 16, 1880: 3.

15 “Base Ball,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, November 26, 1881: 3.

16 “City Brevities,” Denver Republican, June 23, 1882: 8.

17 “A New Catcher,” Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, May 4, 1883: 3.

18 “A New Catcher,”.

19 “A New Catcher.”

20 “Base-Ball,” Clinton (Illinois) Register, August 3, 1883: 2.

21 “The Close of the Base-Ball Season – Manager Barnie’s Contracts,” Baltimore Sun, October 15, 1883: 5.

22 “Cincinnati’s Troubles,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1883: 6.

23 “The Meanest Yet,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 25, 1884:3.

24 “Baltimore Again Shut Out,” Philadelphia Times, July 11, 1886: 10.

25 “Sporting Notes,” Boston Herald, November 10, 1886: 2.

26 Bob Bailey, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-22-1889-sad-sack-louisville-colonels-lose-26th-game-in-a-row/

27 “Thumped the Umpire,” St. Paul Globe, June 27, 1889: 5.

28 “Brutally Beat the Umpire,” Jersey City News. June 27, 1889: 1.

29 “Thumped the Umpire.”

30 “Let Off with Fines,” St. Paul Globe, June 28, 1889: 5.

31 A review of box scores and line scores revealed that he may have played in nine games for Lincoln in 1891.

32 “Base Ball Pointers,” Vanity Fair (Lincoln, Nebraska), May 9, 1891: 5.

33 “Pertaining to Baseball,” Black Hills Times (Deadwood, South Dakota), March 4, 1892: 1.

34 “A Dastardly Act,” Black Hills Weekly Times, July 23, 1892: 2.

35 “City in Brief,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Journal Star, February 21, 1893: 5.

36 “The Athletic Sports,” Salt Lake Herald, March 26, 1893: 3

37 “Wants to Manage Salem,” Portland Morning Oregonian, April 25, 1893: 3.

38 “View from the Bleachers,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening Call, August 18, 1894: 5.

39 “Salary Limit Adopted,” Cedar Rapids Evening (Iowa) Gazette, July 7, 1896: 6.

40 “May Lose the Champs”, Des Moines Register, June 23, 1896: 1

41 “To Meet the Giants,” Cedar Rapids Gazette, July 8, 1896: 8.

42 Gene Gomes, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/abner-powell/

43 Angelo Louisa, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/fred-clarke/

44 Patient # 1,052,498, Official Gazette, U. S. Patent Office, February 11, 1913.

45 “Grandpa Bill’s Scheme,” Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette, December 11, 1896: 7.

46 Rockford (Illinois) Gazette, December 6, 1897: 3.

47 “Obituary. William Traffley, Jr.,” Des Moines Tribune, January 27, 1913: 9.

48 “Deaths,” Baltimore Sun, October 29, 1885: 2.

49 “Boyhood Friend Tells of Traffley.”

50 “William F. Traffley is Dead,” Omaha Bee, June 25, 1908: 11.

Full Name

William Franklin Traffley

Born

December 21, 1859 at Staten Island, NY (USA)

Died

June 23, 1908 at Des Moines, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.