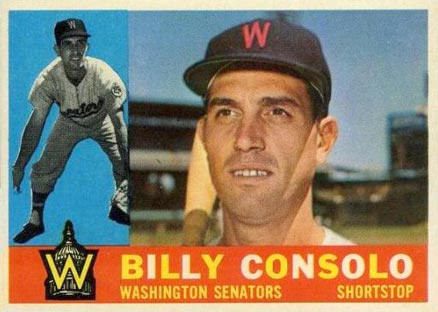

Billy Consolo

William Angelo Consolo was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on August 18, 1934, the same day as Roberto Clemente. His family moved to Los Angeles when he was a child, and at the age of 8, he began playing baseball alongside his brother Horace, who preferred third base. While on the local playgrounds he met George Anderson — later known as Sparky. They signed up at the local park, where it cost 50 cents to play baseball, and a lifelong friendship began. The Twentieth Century movie studio was just around the corner and some of the games they played were against the Our Gang actors and other child stars. Billy began to attract attention from some West Coast scouts while playing on the sandlots. He first attracted notice at the Rancho Cienega Playground; his slingshot arm, base-running speed, and hitting power for a kid his age were bound to generate talk among the scouts spying the amateur ballfields around Los Angeles.

William Angelo Consolo was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on August 18, 1934, the same day as Roberto Clemente. His family moved to Los Angeles when he was a child, and at the age of 8, he began playing baseball alongside his brother Horace, who preferred third base. While on the local playgrounds he met George Anderson — later known as Sparky. They signed up at the local park, where it cost 50 cents to play baseball, and a lifelong friendship began. The Twentieth Century movie studio was just around the corner and some of the games they played were against the Our Gang actors and other child stars. Billy began to attract attention from some West Coast scouts while playing on the sandlots. He first attracted notice at the Rancho Cienega Playground; his slingshot arm, base-running speed, and hitting power for a kid his age were bound to generate talk among the scouts spying the amateur ballfields around Los Angeles.

At the age of 12 Consolo donned his first uniform, with the Douglas Post American Legion. Scouts characterized him as that little scampering runt, playing with boys four and five years older and holding his own quite handily. At 13, Consolo began playing semipro baseball in the California winter league, and crossed paths with future big leaguers Johnny Lindell, Paul Pettit, and Erv Palica. There was plenty of playing time during the long Southern California season. As a proficient cleanup hitter on the Dorsey High School team that won 42 consecutive games and the city championship, Billy advanced to the Crenshaw Legion Post 715 team that won the Junior American Legion National Championship at Detroit’s Briggs Stadium in 1951.

The scouts who paid attention to Consolo’s progress considered him a prize for any team that won the race to sign him. He was called the best prospect Los Angeles had to offer, and everyone waited for him to finish high school in January 1953. Teams courted him in many ways. On a visit to Cleveland with his father in the summer of 1952, the Indians invited Consolo to work out with the team. The club’s director of scouting, Laddy Placek, called him the greatest prospect he’d ever seen, and General Manager Hank Greenberg told Billy, “Don’t do anything until you hear from me.” Greenberg was later blamed for hesitating and losing out on a player who might have solved the Indians’ infield problems.

The Brooklyn Dodgers, a team that signed many of Consolo‘s Legion teammates, also courted him, but Billy ultimately favored the Boston Red Sox. Joe Gordon, representing the Detroit Tigers, was willing to go as high as $100,000, the Consolo family reported, and handling all the offers quickly became unmanageable. The team representatives waving money were all given two hours to promote their offers.

“Boy, I never want to go through that again,” Consolo said. “You really got worries when you’re signing away your future like that. Fellows kept calling me up beforehand and wanting to act as my agent. They didn’t care about me. All they talked about was the money I could get. I decided on the Red Sox because their offer was good and I like the people. They came right out and named a figure and some of these other clubs you couldn’t pin down.”

Ted McGrew, a scout for the Boston Red Sox, arrived with an offer of $60,000 – some reports say $65,000 – in hand for a bonus contract, and Consolo signed on February 2, 1953, the day he graduated from Dorsey High. The Red Sox hoped they had found a second baseman to make plays that hadn’t been seen since the days of Bobby Doerr.

Five players from the Crenshaw Legion team moved on to major-league baseball including Paul Schulte, a right-handed pitcher in the Red Sox farm system, and his sandlot pal, Sparky Anderson, to the Dodgers’ system. Consolo soon followed. He had never experienced the game as a bench warmer, but he would soon. (Amateurs getting bonuses of more than $4,000 were required to stay on major-league rosters for two years.)

The exact terms of the contract were not made public, but it was generally thought Billy got about $15,000 immediately and would receive the balance of $45,000 in three annual installments. The first thing he did was put the bulk of the money in bonds and buy a pair of $25 featherweight baseball shoes that ended up not breaking in as he had expected. He gave the shoes away, bought a new pair, and continued using an old glove he’d had for five years. Lou Boudreau, Boston’s manager, talked him into trying a lighter 33-ounce bat. All this, he hoped, would prepare him for his first experience, just a few weeks from high-school graduation, for life in the big leagues.

Before Consolo made his first major-league hit, a front-office executive for one of the losing teams in the bidding frenzy commented to a sportswriter, “He is a sweet ballplayer. We knew he was a great prospect, too, but with the new bonus rule we wondered how smart it would be to bid big money for him and then stick him on the bench for two years. Now he comes in to pinch-run and maybe he pulls a rock like he did against the Yankees and he goes back to the bench and broods about it for a week, instead of playing and forgetting it. Pretty soon you may have a guy who is so used to sitting on the bench he never makes it as a regular. It’s happened before in this league.”

Boudreau admitted the bench was not the best place for Billy. “Consolo should be out playing every day,” he said. “No sense kidding about it. Billy would be much better off with two years in the minors. He’d come back as a great player. He’s going to be one just the same, but his development may be slower. He certainly has improved a lot from the day he first showed up for spring training in Sarasota.”

Consolo also knew that the minor-league experience would have been to his advantage. “I know it, but I couldn’t afford to pass up the bonus,” he said. “I’ve never sat on the bench in Legion ball or in high school. But I haven’t been wasting my time. I’ve learned a lot by watching.”

Once spring training was finished, Consolo experienced only fleeting moments of an occasional private lesson from the coaches and a few of the regular players. He was stymied by the major-league curveballs that jumped around unlike anything he had experienced back on the Los Angeles playgrounds. Since he was a Red Sox bench warmer he was restricted to a half-hour of batting practice before games, and he rarely got more than his quota of six cuts. He’d ask one of the catchers for a few fastballs and a pitcher for breaking balls in order to become more familiar with big-league curves. When a pitching prospect came by for a tryout, Billy volunteered to stand in at bat.

One day, while the Red Sox were in Washington for a series against the Senators, a cluster of reporters asked Senators manager Bucky Harris — who knew the Boston scene well — for his take on the Boston players.

“Oh, they have got some pretty good boys,” Harris said. “Two or three of them have got a chance to become good ballplayers. But to me they’ve only got one potential star, and he’s not playing.”

The reporters thought he was referring to Jim Piersall, Tom Umphlett, Milt Bolling, or Dick Gernert, but they were surprised at his explanation. “Oh, I guess they are all right, but the kid who takes my eye isn’t playing. It’s that Consolo kid. I can’t explain it, but I spend all my time watching him when the Red Sox are here.”

“Have you ever seen him really play in a game?” asked the reporter.

“No, I haven’t,” said Bucky, “but I’m looking forward to it.”

The next day, May 30, in the first game of a doubleheader, Consolo got into the game — it was his first major-league start — and rewarded Harris for his patience. He came to bat in the fifth inning and smashed a drive against Griffith Stadium’s distant wall in left center, a hit that traveled more than 400 feet and put the Sox ahead 2-1 in a game they won 4-3. The hit impressed Harris no end.

“Even though I wasn’t playing much, when I walked out on the field at age 18 or 19, I said, ‘Here I am playing second base for the Red Sox. I’m one of the best 16 second basemen in baseball.’ I kept that attitude, even though down deep I probably knew I couldn’t do it. But that’s what I felt when I walked out on the field,” Billy said.

During his first year with the Red Sox, Consolo appeared in 47 games and was at bat 65 times, mostly as a pinch-hitter or a fill-in for an injured or ailing everyday player. He made his debut in the second game of an April 20 doubleheader against Washington in Fenway Park, pinch-running for Mickey McDermott in the Red Sox’ seven-run seventh. He grounded out in his first at-bat in the same inning, replaced George Kell at third, and recorded his first major-league assist and error. That he didn’t get into the lineup every day confounded him, despite his understanding about his bonus-baby status. It was several weeks into the season before he gave up the daily habit of checking the starting lineup that Boudreau posted on the clubhouse bulletin board. He waited for his name to appear, and when it did not, he would walk away, shaking his head in astonishment.

The Red Sox finished 1953 in fourth place, an improvement over the sixth-place team of 1952. Ted Williams was back from flying a fighter in Korea and reported for spring training in Sarasota, Florida, in March 1954, and 15 minutes into the first day fell and broke his left collarbone. The team roster needed immediate shuffling while Ted recuperated. The first exhibition game, against the Philadelphia Phillies, found Consolo on second base, where he put on a sensational performance with five assists, four putouts, and two base hits, and earned a bold headline in the Boston Herald: “Consolo Standout As Sox Win, 2-1.”

Lou Boudreau gave Billy a heap of credit for his performance, saying, “He sure handled himself nicely going right or left and belted that ball in the eighth.”

George Kell was impressed, too: “He can run, hit, and field. What more do you need, except probably a little experience?”

Bill Cunningham of the Boston Herald took a special interest in the young players. He frequently stopped by the room shared by Harry Agganis and Consolo in Sarasota and found it had become a gathering place for the younger players. He often found them stretched out on their beds with three or four others occupying the chairs, sitting on suitcases or on the floor. They talked of nothing but baseball, sometimes engaging in arguments over the rule book or trying to call up a newspaperman like Cunningham to settle how to rule a play if there were such dilemmas as “two outs, three men on base, the count three-two on the batter.” He commended them for their devotion to the game and for not spending nights out “studying the nocturnal scenery on Longboat Key, a very pretty diversion, incidentally.”

Reporters who were keeping tabs on the progress of the team encouraged speculation that Consolo would find himself in the starting lineup on Opening Day. If and when Consolo did go to second base for anything like an extended assignment, they wrote, he might stay there as long as Bobby Doerr did, or longer. Even Boudreau, they offered, said Consolo looked about ready. Bill Cunningham offered a warning to second baseman Billy Goodman about the hazard of a star-quality rookie breathing down his neck. The Yankees had Wally Pipp, a stalwart first baseman, conscientious and hard-working. One day he had a headache and chose to sit out a game, and a rookie subbed for him. That rookie was Lou Gehrig. Billy Goodman beware, they warned.

But the Boston front office did not heed their suggestions. The team stayed with its fixtures at second, third, and shortstop, gave first base to Agganis, and Consolo went back to the bench for the second year of his confinement.

Red Sox announcer Curt Gowdy promoted a campaign, “Fill Fenway Park on Opening Day,” but with the absence of Ted Williams in the lineup, the debut of Agganis — nicknamed the Golden Greek and the new hope for 1954 — had to suffice. Billy Goodman would have started at second on Opening Day, but manager Boudreau used a mix of Goodman, Hoot Evers, Charlie Maxwell, and Karl Olson to fill in for Williams. Even so, Consolo started only four games when Goodman was in left during Williams’s injury. Consolo’s sporadic appearances defined his 1954 season. An occasional sensational performance caught the attention of the fans and the reporters, but bench-warming continued to be his primary occupation.

With Consolo’s two-year forced conscription on the Red Sox’ big-league roster over, did the Boston brain trust send him to the minors for playing time, seasoning, experience? Nope. Instead, for year after year, Billy continued to languish on the Red Sox bench.

- 1955: Age 20. The Red Sox, relieved of the bonus-rule restriction, sent Consolo to Oakland, where he played in 159 games, almost all at second base, and batted .276. In Boston, he played in eight games — only four at second — with 18 at-bats. Billy Goodman played 143 games at second, Eddie Joost 19, and Owen Friend and Grady Hatton one each.

- 1956: Age 21. Goodman again ruled the roost, getting 95 starts at the keystone sack. Ted Lepcio vaulted above Consolo on the depth chart, with 52 starts. Even September acquisition Gene Mauch got six starts in his one month with the Red Sox. Billy got all of two starts at second and played 58? innings total there over 25 games.

- 1957: Age 22. Despite Goodman’s having been exiled to pinch-hit duty, Consolo became the fourth-stringer at second. Lepcio took a plurality (61) of starts at second base. Gene Mauch had 56, and Ken Aspromonte started 23 games to Consolo’s 14. However, Billy saw more action at shortstop (42 games, 38 starts, 350? innings total) than at second, and even put in a couple of games at third base.

- 1958: Age 23. Consolo was the third option at second, having gotten more playing time than Aspromonte at least, but well behind new second sacker Pete Runnels and the demoted Lepcio. He was also the third choice at shortstop behind new would-be infield sensation Don Buddin and Billy Klaus. Consolo was the second-stringer at third base, but he got in just one inning of work behind 1958 iron man Frank Malzone. Consolo hit a dreadful .125 in 72 at-bats.

- 1959: Age 24. Consolo was not only out of the picture at third base — Malzone played every inning of the season — but also, surprisingly, at second base. Runnels, Pumpsie Green, Herb Plews, and Lepcio saw action there, as did in-season acquisition Bobby Avila. Consolo started a pair of games at shortstop and was confined to pinch-hitting or pinch-running duty otherwise. Soon, he would be out of the picture altogether for Boston.

On June 10, 1959, in the last game Consolo played in a Red Sox uniform, he committed an error that led to an unearned run that put the game out of reach for Boston despite a furious comeback which left the Red Sox one run short in a 10-9 loss to the Detroit Tigers. On June 11, four days before the trading deadline, the Red Sox made a two-for-two swap, sending right-handed pitcher Murray Wall and Consolo to the Washington Senators for infielder Herb Plews and pitcher Dick Hyde.

Immediately there was trouble with the trade when Hyde revealed that he had a sore arm and would be unlikely to pitch for some time. Hyde and Wall were “reverse traded” while Consolo stayed with the Senators and Plews with the Red Sox. Consolo finally received his chance to spend less time on a bench and more time out on the field, appearing in 79 games, nearly all at shortstop, In 1959 Consolo had 216 at-bats, his most since 1954 (the last season he played under Lou Boudreau), when he had 242. He finished the season in Washington with a .213 average.

Cookie Lavagetto, Washington’s manager for 1960, anticipated a dilemma at second base in 1960 and found no easy solution. Although he had converted Consolo to shortstop, he had shortstop Zoilo Versalles, whom he had given a late-season tryout at short in 1959, looking ready to take on the position full time. He was willing to give Billy the first crack at second, saying, “Consolo at second could step up our double-play production. He has more range than any of the other candidates, and when he teams up with Versalles, it could be a pleasure to watch.”

But as it turned out, Versalles appeared in just 15 regular-season games, from September 13 to October 2, at shortstop, while Consolo appeared there in 100 games as well as a handful at second and third. Although his fielding was commendable, his bat still betrayed him. His average was a dismal .207. He was released at the end of the season.

Despite his release, the Minnesota Twins, newly relocated from Washington, signed Consolo in 1961 to a look-see deal. He made the team out of spring training, but appeared in just 11 games with only five at-bats, appearing in his last game on May 28, at second base. Jose Valdivielso, another former Senator, despite an equally anemic batting average of .195, edged Consolo out as Lavagetto’s utility infielder. On June 1, in order to improve their pinch-hitting strength — pinch-hitters had gone 9-for-61, a .147 average — the Twins traded Consolo to the Milwaukee Braves for infielder Billy Martin, and the Braves immediately sent Consolo to Milwaukee’s Triple-A team, the Vancouver Mounties.

Consolo gave serious thought to retiring from baseball when he was traded to the Braves, but by mid-July he was adjusting to the minor-league environment and started hitting doubles and triples again, scoring 63 runs and tallying 40 RBIs with a .283 average in 99 games, showing some of the stuff that had once attracted the attention of scouts and managers. To retain him on their roster, the Braves brought Consolo up just before the October 17 deadline. Although he never played a major-league game for the Braves, he was kept as future trade material.

During the Rule 5 major-league draft in November 1961, the Phillies picked Consolo. Still branded in the press as the Red Sox bonus player, Consolo was expected to handle second or third base capably.

Consolo’s career in a Phillies uniform was brief, as he appeared in just 13 games in 1962, only once in the field, and on May 8 he was sold to his hometown Los Angeles Angels. General Manager Fred Haney picked up Consolo as insurance for the infield because Billy Moran had been sidelined in September 1961 with a back injury. Although Moran was holding his own so far, Haney didn’t want to be caught without a utility player if Moran’s back gave out again.

Soon enough it was apparent that Moran’s back was going to hold up just fine, as he appeared in 160 games for the Angels. Consolo got into 28 games as a backup infielder, pinch-hitter and pinch-runner. On June 26 the Angels put him on waivers and the Kansas City Athletics picked him up. Consolo appeared at shortstop with the Athletics that day. He replaced Dick Howser, who was sidelined for seven weeks after he fractured his left hand putting a tag on Luis Aparicio against the White Sox two days before.

Kansas City afforded Consolo more playing time than he’d seen in years. He appeared in 54 games — 48 at shortstop, with 42 of those starts — and got 154 at-bats. His average of .240 was his best in five years. None of that mattered. Kansas City tried to send him to the minors, thinking he had only four years of major-league experience and that he was much older than his reported 28 years. Billy requested his unconditional release, pointing out that he met the requirement of eight years of major-league experience, and that meant the trip to the minors was without his consent. He got his release on November 2, and in 1963 he was signed by the Cleveland Indians and offered a trial at their spring-training camp and a minor-league contract with the Jacksonville Suns of the International League. When it came to returning him to Jacksonville, Consolo gave serious consideration to leaving baseball. Billy informed Indians personnel director Hoot Evers, an old teammate from Boston, “I’m going back home to Los Angeles to think it over.” Evers said he would have been surprised if Billy returned.

With his decision made, Billy retired from baseball, having appeared in 603 big-league games over 10 years for six teams, with 1,178 at-bats, 260 hits, 158 runs, and a lifetime average of .221. He turned to his offseason career as a barber, an occupation he inherited from his father, and ran a 12-chair shop at the Los Angeles Statler Hilton Hotel, little realizing at the time that the job would prepare him for his next career in baseball. The haircut may have cost a buck or two, but the baseball talk came at no extra charge. His boyhood friend Sparky Anderson, not having made it as far as a player as Billy had, was making a name for himself as a major-league manager in Cincinnati, having guided the Reds to World Series wins in 1975 and 1976. During the 1979 season, he became the manager of the Detroit Tigers and asked Consolo if he’d be interested in returning to baseball.

“There was no decision to make. It was like being rejuvenated. Sparky asked me how long I needed to make a decision and I told him about three seconds.”

Sparky vowed to go all the way to the World Series, but the 1979 Detroit team he inherited required more work than he anticipated. While some of the coaches carried out Anderson’s directives and assisted with the player pushing, Billy Consolo’s job was twofold. He was known for his ability to lighten up the mood of the clubhouse, his way of taking pressure off with his humor and supply of tall tales. Any player who thought the worst had happened to him could count on Billy to come up with something even worse. He could talk about anything: the price of haircuts, what they used to talk about at King Arthur’s Round Table, or the height of the fence in center field at Fenway Park. “Billy was a beautiful storyteller,” wrote Dan Ewald, a former sportswriter and Tigers executive. “He could spin a story you might think was 100 percent true. It might have been. Sometimes, when he would tell one of them again, you’d get a new piece. That made it worth listening to the old stories.”

Consolo’s second role required him to provide a sane environment for his lifelong friend. Sparky Anderson’s volatile moods were a hazard to his players as well as his own well-being. Billy served Sparky well on his staff, and was always close at hand to keep him grounded. When Sparky, mentally and physically exhausted from the relentless grind of managing a club that tried its best but came up short in 1989, was sent home to California to recuperate, Billy Consolo, his friend since they dominated the sandlots of Los Angeles and who lived with him during the season, accompanied Sparky on the way home. Billy stayed with Sparky until 1992. Ten years (two of them consisting of fewer than a dozen games) playing major-league baseball, and 14 years on the coaching staff, left Billy Consolo with no regrets about his baseball career. He died on March 27, 2008.

Looking back on his best of times, he once said: “I never felt like anybody the Red Sox ever brought up was better than I was. But when they played every day, you could tell that somebody saw something in them. Baseball players, when you know they can play, you see it early. Not that you’re going to quit or anything like that, but they have something. I think any baseball player, when he gets beat out of a position or a job, it’s nothing against the guy. They just see something better in the other guy. They are there for a reason.”

Sources

Publications

Anderson, Sparky, with Dan Ewald. Bless You Boys. Diary of the Detroit Tigers’ 1984 Season. Chicago: Contemporary Books. 1984.

Anderson, Sparky, with Dan Ewald. Sparky! New York: Prentice Hall. 1990.

Light, Jonathan Fraser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball, Second Edition. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. 2005.

Kelley, Brent. Baseball’s Bonus Babies. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. 2006.

Snyder, John. Red Sox Journal. Cincinnati: Emmis Books. 2006.

Articles

Ballew, Bill. “Tigers’ Coach Billy Consolo Back With Sparky Again.” Sports Collectors Digest, June 2, 1995. 160-162.

Birtwell, Roger. “Rookie’s Father Says Other Clubs Wanted to ‘Fiddle Around’ Too Much.” Boston Globe, April 30, 1953. 21.

Boudreau, Lou, “Managing a Young Team.” Atlantic Monthly, August 1953. Boston. 76-79.

Carmichael, John P. “Veeck Had Scheme to Sign Consolo.” Boston Globe, March 16, 1954. 6.

“Consolo To Be Inducted Into National Guard.” Cumberland (Md.) Evening Times, July 25, 1957. 31.

Costello, Ed. “Consolo Standout As Sox Win, 2-1.” Boston Herald, March 9, 1954. 11-12.

Cunningham, Bill. “Consolo, Agganis Real Competitors.” Boston Herald, March 10, 1954. 29.

Cunningham, Bill. “Boudreau Rates Sox Dark Horse.” Boston Herald, March 14, 1955, 9.

Dyer, Braven. “Slick DP Combo Throws Lifeline to Angel Hurlers.” The Sporting News, May 23, 1962. 32.

“Goodman In LF As Bosox Make Infield Shift.” Troy (N.Y.) Record, April 29, 1954. 34.

Hirshberg, Al. “Bosox Lidlifter Lineup About Set as Drilling Starts.” The Sporting News, February 25, 1953.14.

Hurwitz, Hy.“Red Sox’ Latest Bonus Baby Wishes He Could Be Shipped to Minors.” The Sporting News, March 11, 1953. 11.

Hurwitz, Hy. “Yawkey High on Consolo as Kid Prospect.” The Sporting News, May 20, 1953. 4.

Hurwitz, Hy. “Red Hot Job Battles Seen at Four Spots in Camp of Red Sox.” The Sporting News, February 26, 1958. 19.

Hurwitz, Hy. “Red Sox Land Hyde in 4-Man Deal With Nats.” The Sporting News, June 17, 1959. 18.

Hurwitz, Hy. “Consolo Reached Red Sox in One Hop.” The Sporting News, July 15, 1953. 4.

Hurwitz, Hy. “Some Bosox Bonus Talent in Final Test.” The Sporting News, November 26, 1958. 30.

Kahan, Oscar. “Total of 35 Choices biggest Grab-Bag Haul in 47 Years.” The Sporting News, December 6, 1961. 9.

King, Joe. “Amalfitano Rated Prize Bonus Boy.” Boston Globe, February 26, 1954. 21.

King, Joe. “Few Prize Pay-Offs In Bonus Plunges. Five Standouts, Many Flops in Five Years.” The Sporting News, November 20, 1957. 1-2.

Lebovitz, Hal. “Consolo May Call It Quits After Failing With Indians.” The Sporting News, April 6, 1963.

Lewis, Allen. “Phils See Roy as Big Hypo to Flimsy Attack.” The Sporting News, December 6, 1961, 30.

Lewis, Allen. “Mauch Paints Phils’ Future in Rosy Color.” The Sporting News, February 7, 1962. 24.

Lewis, Allen. “Carey’s Loss Sparks Talk of Phil Swap.” The Sporting News, March 7, 1962. 21.

Lowe, John. “Westlake Resident Remembered as ‘Beautiful Storyteller.’” Detroit Free Press, April 3, 2008.

“Major Flashes.” The Sporting News, March 25, 1959. 26.

Mehl, Ernest. “Howser Injury Deals Kaycee Rugged Blow.” The Sporting News, July 7, 1962. 42.

Montville, Leigh, “Not So Easy Riding on the Red Sox Bus.” Boston Globe, March 25, 1981. 1.

Newcombe, Jack. “$60,000 Bench Warmer.” Sport Magazine, September, 1953. 22-59.

Povich, Shirley. “Nats Hoping Killebrew Shadow Will Spur Yost.” The Sporting News, January 8, 1958. 4.

Povich, Shirley. “Consolo Top Banana Among Bunch of Six on Nat Keystone List.” The Sporting News, February 24, 1960. 16.

Sampson, Arthur. “Only White, Kell, Goodman Set – Boudreau.” Boston Herald, January 27, 1953, 17.

Sampson, Arthur. “Consolo Has Right Attitude to Become a Star.” Boston Sunday Herald, March 7, 1954. 44.

Sampson, Arthur. “Sox Situation Not Hopeless — Yawkey.” Boston Herald, June 2, 1959. 25.

Siegel. Arthur. “Ex-Sox Bonus Player Consolo Quits Baseball.” Boston Globe, March 27, 1963. 49.

Other

Nowlin, Bill. “Consolo on Runnels and Williams, and More.” Interview. February 2000.

Full Name

William Angelo Consolo

Born

August 18, 1934 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

March 27, 2008 at Westlake Village, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.