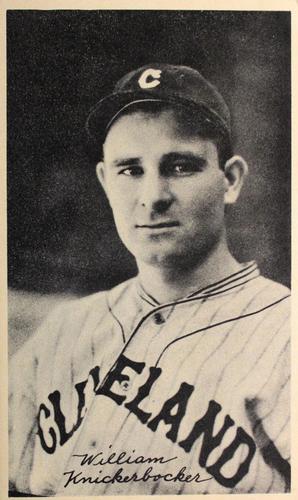

Bill Knickerbocker

In the California winter leagues of 1929, California resident and Toledo Mud Hens manager Casey Stengel spotted a hard-hitting shortstop named Bill Knickerbocker. Stengel convinced the teenager to try out for the Mud Hens in the spring. The youngster hitch-hiked across the country in 1930 to join Toledo at spring training in Anniston, Alabama. Knickerbocker saw action at shortstop and second base during the exhibition season for the Hens.

Under the rules of the American Association, teams could have up to 20 players on a reserve squad. Knickerbocker was reserved and went north with the rest of the team. The reserves played occasionally in intra-squad matchups and against area teams. Hoping to get Knickerbocker some meaningful action, he was optioned to Decatur on May 21.

The Decatur Commodores of the Class B Three-I League were in Bloomington, Illinois, when Bill arrived. Manager Rube Dessau started him in the second game of the May 25 doubleheader which the Commies lost, 2-1, in 11 innings. Knickerbocker’s throwing error in the second plated the first run for Bloomington. At the plate he had an infield single before being replaced by regular shortstop Dan Jessee in the eighth.1

Decatur had needs besides a backup infielder and did not retain Knickerbocker. Toledo was unable to find a team to take him. “As a result, Bill was placed on the ineligible list …” and spent the bulk of the summer learning by watching.2

In September, Knickerbocker finally garnered some playing time with the Mud Hens. Box scores from The Sporting News show him playing six games from September 7 through 21. At the plate he had nine hits, including two doubles and two triples, in 20 at-bats. In the field he made four errors. The teenager was finally on his way to a career that would last until the war.

William Hart Knickerbocker was the first of four children born to William H. and Margaret Antoinette Knickerbocker. He joined the family in Los Angeles on December 29, 1911. The Knickerbocker clan was of Dutch descent and had worked its way across the continent. The older William was born in Arkansas to Frank and Laura Knickerbocker. Laura gave birth to nine children, seven of whom survived to make the move to California in the early 1900s. Bill’s mother (Margaret) was of Austrian descent. The elder William worked as a delivery driver for an ice company. He later became the foreman for the company.

Knickerbocker would live in California his entire life. After his career started, he had several residences in Whittier. In 1956 he and his wife, the former Willda Mary McHolland, moved to Sebastopol, California, in Sonoma County wine country.

Knickerbocker attended school in Los Angeles and graduated from Roosevelt High School. He had the size for athletics: 5-foot-11 and between 165-to-170 pounds. His father had been quite athletic and may have played some minor league ball in Arkansas before the family moved to California. In school Bill played four sports. He was a quarterback in football, a forward in basketball, a miler on the track team, and shortstop in baseball. He threw and batted right-handed and developed a keen instinct for the game. “I live and eat baseball. My life is wrapped up in it. I can’t think of a day when I won’t hope to have something to do with baseball.”3

He reportedly batted .500 and .472 in his last two seasons as a high-school second baseman. After graduation he spent two seasons playing semipro baseball. That usually meant two games a week and he again played second base.4

Bill reported to training camp in Miami in 1931 with the Mud Hens. He had grown since his first season and had added some strength.5 Stengel had five infielders in camp and shuffled them amongst the positions to see where they best fit. He continued to juggle the lineup during the season. Knickerbocker played more shortstop (66 games) than anyone else and spent 28 games at third base. Bill’s .283 batting average looks good until compared to the more than 60 men who broke the .300 mark in the league that year.

Toledo finished last in 1931 and Bibb Falk came in as manager in 1932. He stopped the revolving door in the infield and handed the shortstop job to Knickerbocker. Bill responded with a tremendous season with the bat. Playing 160 games at short he gathered 234 hits (third in the circuit) while smacking a whopping 69 doubles.

The major league record for doubles is 67 held by Earl Webb. Ironically, while Knickerbocker topped Webb’s mark, he was not able to surpass the Toledo record. That was set in 1900 by Erve Beck with 71 in the Interstate League. In fact, Knickerbocker’s performance does not even place him in the top ten totals in minor league history. Lyman Lamb leads the pack with 100 two-baggers in 1924.

The Cleveland Indians had a working agreement with Toledo that gave them priority on acquiring players. Manager Roger Peckinpaugh, General Manager Billy Evans, and scouts all attended the Toledo game on June 6 to see Knickerbocker in action. Bill made a statement by getting three hits as leadoff batter.6 On August 1 the Tribe purchased Knickerbocker’s contract for $15,000.7

The Indians made it clear that they wanted Knickerbocker on their 1933 roster and Bill was ready for the jump, but he played it cool. He was slow to return his contract, suggesting a possible holdout, but then “joined the fold in plenty of time” for the opening of spring training in New Orleans.8 His initial big-league salary was $3,600.

Benefiting from a string of injuries to incumbent Johnny Burnett, Knickerbocker seized on the opportunity to win the starting job at shortstop. He had a brilliant spring and was installed as the number-two hitter. Unfortunately, his bat cooled when the team started playing games that counted. By late April he was batting .114. He was moved to the bottom third of the lineup. Finally, in mid-May he was benched for two weeks.

Manager Peckinpaugh was fired and replaced by Walter Johnson, who returned Bill to the lineup. He held down shortstop until he “suffered a severe spike wound … his foot was cut to the bone by the spikes of Harry Davis, Detroit first baseman.”9 He missed the entire month of August because of the injury. Bill closed out the season playing 80 games and batting .226.

Johnson expressed confidence in the spring of 1934 that Bill was ready to take over short fulltime. He must have been second-guessing himself as it came time to head north. The local paper reported that “Knickerbocker has been erratic in the field and all but helpless at the plate.”10 Nevertheless, Johnson stuck with the now 22-year-old. His faith was rewarded when Bill “snapped out of his spring training lethargy” to play inspired defense and raise his average over .400 by the end of April.11 Knickerbocker’s hot bat continued.

In mid-June, Associated Press writer Eddie Neil claimed Bill’s bat and defense made him the logical choice for American League shortstop in the upcoming All-Star game.12 Neil was in the minority and the job went to Joe Cronin. On July 2, Knickerbocker tore a fingernail off in a tag play. The injury sidelined him until after the All-Star game.

In the second half of the season, Bill started to wear down. His average would slowly drop from the .350s until it closed at .317, which was third amongst Indians regulars. His fielding percentage of .962 was one of the league’s best, however his range factor was well below the average.

Despite tough economic times, the success of 1934 allowed Evans to slacken the purse strings. After a bit of dickering, Knickerbocker signed for a $2,500 raise to $7,000. He was slated to be the Tribe’s leadoff hitter until he was rushed to the hospital in New Orleans on March 16. An emergency appendectomy put him on the shelf until May.

After a few pinch-hitting appearances, he finally entered the lineup on May 22 in a loss to the Red Sox in Fenway Park. The 1935 season seemed to be jinxed for the Tribe. An excessive number of rainouts and schedule changes led to 18 doubleheaders in August and September. Bill’s season was impacted by his surgery. Some of his teammates developed less typical injuries including severe sunburn, fireworks injuries, and fits of insomnia.

Even when things went right, there were unexpected outcomes. On August 19, Knickerbocker blasted a ball to right field in Cleveland that became wedged in the fence mesh. Things got even weirder on September 7 at Fenway Park. The Tribe was ahead, 5-1, going into the ninth behind Mel Harder. The Red Sox rallied and banged four straight singles. Oral Hildebrand was brought in to relieve and loaded the bases with another single. Joe Cronin came to the plate and scorched a line drive towards third base that bounced off Odell Hale’s head. Knickerbocker snagged the carom on the fly. He tossed to Roy Hughes at second who relayed to first for a game-ending triple play.13

Cleveland finished in third place with 82 wins. Knickerbocker batted .298. He had a 12-game hitting streak in July, but the team only won three of those games. He started the streak batting .295 and ended it the same way. That winter Bill played with the Pirrone Stars in California. He played second base because The Sporting News MVP Arky Vaughn was at shortstop.

Manager Steve O’Neill enjoyed a Cleveland rarity in 1936: All four of his infielders played over 150 games. Knickerbocker saw the most action of anyone on the team. He sat out a doubleheader on September 6 versus the White Sox. Those were the only innings he missed the entire season. His fielding percentage was average and despite a reputation as a slick, speedy infielder his range factor was better than only one other regular American League shortstop, Detroit’s Billy Rogell.

His performance at the plate was much more impressive, as he set personal major-league highs for doubles (35), home runs (8), runs batted in (73), walks (56), and on-base percentage (.354). Never very successful as a base stealer, he was caught in 14-of-19 tries, which led the league.

In January, St. Louis manager Rogers Hornsby authored a trade between the Browns and the Indians. St. Louis sent outfielder Moose Solters, shortstop Lyn Lary, and pitcher Ivy Andrews to the lakefront. The Tribe shipped hometown favorite Joe Vosmik, Knickerbocker, and Hildebrand to the Browns. Sportswriters hailed it as the biggest swap of the winter.14

The Browns trained in San Antonio and Knickerbocker came down with a sore arm on March 17 that put him on light duty. Fortunately, he only missed three days of work. Soon after he claimed the leadoff position in the batting order for Opening Day. He gave his new owners and fans plenty to cheer about in the 15-10 win over the White Sox. He had four hits, including two doubles, scored three times, and had four RBIs.

Knickerbocker played the iron man role at shortstop until the end of August when interim manager Jim Bottomley switched him with second baseman Tom Carey. The swap lasted until September 6 (Labor Day) when Knickerbocker injured his hand and sat out the rest of the season.

That winter Knickerbocker returned the initial contract from the team unsigned because it called for a pay cut. Browns’ business manager William O. DeWitt responded to the unsigned contact with a message asking Knickerbocker’s minor-league preferences. “We like to make it as congenial as possible for players we send to the minor leagues.”15 About a month later, he was swapped to the Yankees for infielder Don Heffner and cash.

The conventional wisdom was that the Yanks obtained Knickerbocker for his bat and to replace rookie Joe Gordon if the youngster stumbled. Gordon was hitting poorly at the end of April (.156) when he rushed into the outfield after a short flyball off the bat of Washington’s Taft Wright. Gordon and Joe DiMaggio collided with a “sickening thud.” Both men suffered concussions and were sent to the hospital immediately.16

Knickerbocker took over at second base and was intent upon making it his own. The Yankees went on a seven-game winning streak with him at second. Knickerbocker was hardly tearing the cover off the ball, but he was playing well defensively. He and Frankie Crosetti made a fine double-play combo. Manager Joe McCarthy praised him and stated that Bill had the job, “as long as he continues his present playing clip.”17

Knickerbocker never really stopped playing at his “clip” but lost his job anyway. McCarthy returned Gordon to the lineup on June 9 despite Knickerbocker getting hits in 14-of-16 games from May 25 through June 8. Knickerbocker never started another game that year. Used sparingly, he had 12 at-bats the rest of the way. He watched the Yankees’ World Series sweep of the Cubs from the bench.

The 1939 season found Yankee infielders Gordon, Crosetti, and Red Rolfe playing over 150 games each. Knickerbocker’s service was seldom needed. He made only one start and only batted 13 times. Again, he watched the Yankee World Series sweep from the comfort of the dugout.

The seasons with the Yankees were financially beneficial for Knickerbocker, though. His regular season salary was estimated to be $9,000. Each of the World Series shares he earned were over $5,500.18 In contrast, the average income for Americans hovered around $1,700 at the tail end of The Great Depression.19

Knickerbocker saw the field a bit more in 1940. Crosetti was benched for a week in mid-May. When Crosetti returned, Bill took over at third for a dozen games. Knickerbocker did his job superbly. The Yankees were 13-5 during the stretch and he batted .306. He made only 10 starts after June 4 and saw his batting drop off to .242. That winter he was traded to the Chicago White Sox for catcher Ken Silvestri.

The White Sox trained in Pasadena, California, under manager Jimmy Dykes. He held an early camp and was pleased when Knickerbocker drove from his Whittier home to work out daily. When camp officially opened March 2, Knickerbocker had made a big enough impression to be considered the front-runner for the second-base job.20 He held off a challenge from rookie Don Kolloway and opened the season as the leadoff hitter.

Knickerbocker’s best game of 1941 came on May 28 versus the Browns. He went four-for-four with a double, two triples, and a hit-by-pitch. Surprisingly he only scored once and had no RBIs as the Sox lost, 8-4. He went through a slump in mid-July that dropped his average 20 points to .252. On July 24 he slammed a foul off his shin. The bruise cost him nearly a month on the bench as Kolloway got hot and raised his batting average from the .170s to .260.

When Kolloway experienced knee issues, Knickerbocker returned to the lineup on August 22. The two men would split second-base duties the remainder of the season. Knickerbocker closed out the year batting .245. He went to spring training in 1942 with the Sox, but at the end of camp was placed on waivers and claimed by the Philadelphia Athletics.

Knickerbocker was handed the second-base job and took over as the number-two batter in the lineup. He paid an early dividend when he walloped a tenth-inning home run on April 17 to give the A’s their first win of the season, beating Washington, 5-4. His batting average was hovering around. 300 when he took a line drive to his left thumb on May 1. He did not regain his starting spot until June 9 because of the digit dislocation.

He held onto the starting job into August, then Connie Mack took a long look at Crash Davis. The A’s placed Bill on waivers following the season and he was picked up by the Yankees. His career was winding down and Knickerbocker was slow to report to the Yankees, arriving ten days late for camp. He made the expanded roster but was released on May 9, just as the team was leaving for their western swing.

He returned to California and joined the Hollywood Stars in the Pacific Coast League for 68 games before a broken foot ended his career. In April 1944 he joined the Army, putting in two years of service with the military police.

After his military service, he settled down to life with Willda and their daughters, Diane and Judy. Bill became an avid golfer in his leisure time. He lost the inaugural Pacific Coast Baseball Players tournament to Fern Bell.21 Bill became a fixture at the event. Professionally he was a liquor salesman. When he moved the family to Sebastopol, California, they purchased a local café. How successful that venture was is unknown. Bill died of a heart attack on September 8, 1963, at 51. In addition to his wife and daughters, he left four grandchildren.

Bill was a Catholic, and a funeral mass was conducted for him, following which he was buried with full military honors in the Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California. His 69 doubles in the American Association will forever stand as the league record for the circuit, which dissolved in 1997.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Joel Barnhart, and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Bob Sink, “Bloomers Three Homers Win First; Krueger Bests Tesar in Pitching Duel in Second,” The Decatur Herald, May 26, 1930: 5.

2 Robert French, Toledo Blade, March 11, 1931: 20.

3 Ralph Kelly, “Knickerbocker Aims to be Only a Baseball Player,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 11, 1933: 13.

4 “With the Mud Hens,” Anniston Star, March 10, 1930: 8.

5 French, Toledo Blade.

6 “Four-Run Lead,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 7, 1932: 13.

7 “Buy Bill Knickerbocker,” The Indianapolis Star, August 2, 1932: 12.

8 Gordon Cobbledick, “Roy Spencer Signs; 4 on Holdout List,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 1, 1933: 14.

9 “Bill Knickerbocker Spiked, Out for Several Weeks,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 30, 1933: 17.

10 Gordon Cobbledick, “Glenn Wright, ex-Pirate, May Become Indian, Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 9, 1934: 17.

11 “Three Indians Regulars Swat in .300 Class,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 28, 1934: 19.

12 Sam Otis, “Rates Knickerbocker No. 1 for All-Star Shortstop,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 18, 1934: 17.

13 “Indians Turn in Fast Triple Play,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 8, 1935: 31.

14 “Indians Send Hildebrand, Knickerbocker and Vosmik to Browns for Three Others,” The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), January 18, 1937: 14.

15 “So- Do You Like Minors?,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 19, 1938: 21.

16 Francis E. Stan, “Yankees Lose DiMag, Gordon in Crash, but Win Over Nats, 8-4,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 1, 1938: 30.

17 “Joe Gordon Loses his Job to Billy Knickerbocker,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 11, 1938: 18.

18 Baseball Almanac, “World Series Gate Receipts,” http://www.baseball-almanac.com/ws/wsshares.shtml. Accessed October 24, 2018.

19 “Check Out the Cost of Living in 1938,” https://www.businessinsider.com/the-cost-of-living-2014-10. Accessed October 24, 2018.

20 Irving Vaughan, “Dykes Finds ‘Knick’ a Handy Knick-Knack,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1940: 1.

21 “Fern Bell Wins Golf Tourney,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1940: 7.

Full Name

William Hart Knickerbocker

Born

December 29, 1911 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

September 8, 1963 at Sebastopol, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.