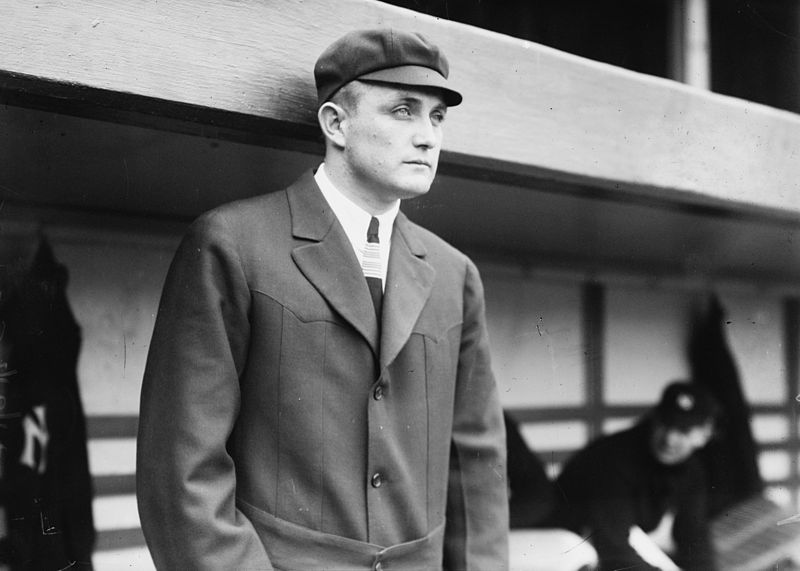

Billy Evans

Billy Evans had one of the most varied nonplaying careers in baseball history. The third umpire to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, Evans umpired from 1906 to 1927 during most of the Deadball Era in the American League, and augmented his umpire’s salary by writing a nationally syndicated sports column, “Billy Evans Says,” as the sports editor of the Newspaper Enterprise Association. Prior to that, he had written columns that appeared in more than 100 newspapers across the country covering varied topics as player personalities, umpiring techniques, and the World Series. In doing this, he promoted and understanding of the game and its stars in the early 20th century. A popular offering was a frequent column on strategy and rules, with the pointed question, “What Would You Do?”1

Billy Evans had one of the most varied nonplaying careers in baseball history. The third umpire to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, Evans umpired from 1906 to 1927 during most of the Deadball Era in the American League, and augmented his umpire’s salary by writing a nationally syndicated sports column, “Billy Evans Says,” as the sports editor of the Newspaper Enterprise Association. Prior to that, he had written columns that appeared in more than 100 newspapers across the country covering varied topics as player personalities, umpiring techniques, and the World Series. In doing this, he promoted and understanding of the game and its stars in the early 20th century. A popular offering was a frequent column on strategy and rules, with the pointed question, “What Would You Do?”1

Born in Chicago on February 10, 1884, William George Evans grew up in Youngstown, Ohio, where his father, a Welsh immigrant, worked as a superintendent in a Carnegie Steel mill. As a youngster he participated in YMCA sports programs and a local baseball team, the Youngstown Spiders, named after the Cleveland Spiders. Billy enrolled at Cornell University in 1901. Having excelled in baseball, football, and track in high school, Evans played freshman football and baseball at Cornell University. His baseball coach, former Baltimore Orioles player and future Detroit Tigers manager Hughie Jennings, called Evans a fine outfielder, but Billy’s playing days ended with a football-related knee injury.

Evans spent 2½ years at Cornell studying law before his father’s death forced him to leave school in 1902 to help support his family. He became a newspaper reporter, securing a job with the Youngstown Vindicator for $15 a week, and soon became the newspaper’s sports editor.2 Also in 1902, Evans began umpiring local baseball games. When the scheduled umpire failed to appear due to illness for an Ohio Protective Association game between the Youngstown Works club and a team from Homestead, Pennsylvania, Evans was persuaded to umpire the contest. He wound up working in the league as a substitute for a few more days, and was then hired as a regular umpire for $150 a month, a substantial increase from his newspaper salary.

In 1904 Evans joined the Class-C Ohio-Pennsylvania League. In 1905 he visited a clothing store in Youngstown owned by former Cleveland outfielder Jimmy McAleer, now manager of the St. Louis Browns, who told Evans he had seen him umpire and liked what he saw. McAleer recommended Evans to American League President Ban Johnson. McAleer had witnessed a game between Youngstown and Niles in which a Niles batter fell down after being hit by the pitcher. But Evans called the pitch a strike, ending the game. Evans had to be escorted from the field by police and Niles manager Charley Crowe.3

Acting on McAleer’s advice, Johnson offered Evans $2,400 per year plus a $600 bonus to umpire in the American League in 1906. Evans said that looked like all the money in the world and claimed to break all speed records in getting his acceptance back to Johnson in a tersely-worded telegram reply saying, “Yes and thanks!”4 Known as Big Boy Blue or the Boy Umpire, Evans was the youngest umpire to be hired by the majors when he joined the American League in 1906 at the age of 22. (The Sporting News obituary said that Evans rose from a Class-D minor league to the major leagues, but the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball5 reports that the Ohio-Pennsylvania League was Class C.) Evans subsequently became, at 25, the youngest World Series umpire.

Being an umpire during the Deadball Era was not a comfortable position to be in as then a single umpire worked most games. Through his actions and on-field judgment, Evans built a reputation as one of the fairest arbiters in the game.6

Unique among his profession, Evans openly admitted that he was fallible and could make mistakes. The man behind the plate for Walter Johnson’s first major-league game, Evans later confessed that Johnson’s fastball sometimes came to the plate so quickly that he would close his eyes before making a call. “Why, do you know, Johnson was the only pitcher I ever closed my eyes on, in automatic self-defense, in spite of wearing a mask and having a catcher standing in front of me as extra protection,” he once said.7

“The public wouldn’t like the perfect umpire in every game,” Evans contended. “It would kill off baseball’s greatest alibi – ‘We wuz robbed.’”

After Evans became a major-league umpire, he had a confrontation with Hughie Jennings on May 22, 1907. “In the tenth Detroit’s coaches sent (Boss) Schmidt in from second on (Charley) O’Leary’s double but Umpire Evans, on (Monte) Cross’ appeal, declared Schmidt out for not touching third base. The spectators swarmed the field and Evans had to call for police protection; at the same time he sent Manager (Hughie) Jennings to the club house.”8 Detroit won the game in the 11th and Jennings was suspended.

Evans quickly built a reputation as a “fair and square umpire” capable of handling any situation that arose on the diamond. He often said the trick of umpiring relied upon three talents: the ability to study human nature and apply the findings, the ability to be at the right angle to make a call and the ability to bear no malice. Billy demonstrated this third skill in St. Louis in September 1907, when his skull was fractured by a bottle thrown by a 17-year-old fan after a controversial call. Ban Johnson came to St. Louis to announce he had hired an attorney and would prosecute the young offender. To his dismay, however, Evans refused to press charges, saying the youth’s parents were nice people and the kid had apologized for throwing the bottle.9

But Evans was not a saint. If pushed he would not back down, and in September 1921 was involved in a fistfight with Ty Cobb under the stands after a game. According to the Washington Star, Cobb was irate over over Evans’s calling him out at second on a steal attempt. During the argument Cobb reportedly told Evans that he would whip him right at home plate, but would not do so because he knew he would be suspended. Evans invited Cobb to the umpires’ dressing room for the postgame festivities. The brawl itself took place under the stands, with players from both teams forming a ring for the combatants. According to some accounts of the incident, the fight ended in a draw and was the bloodiest they had ever seen. Cobb was suspended for the next game, which Evans umpired wearing bandages.10

Among his colleagues, Evans was well known as a mentor for young umpires, generous with his time and advice. Evans also became a strong advocate for the establishment of formal school training for umpires to meet the growing demand for officials. He was highly critical of Organized Baseball for doing little about the situation. Ironically, if the present-day umpire-school system existed during the Deadball Era, Evans would probably have never gotten a chance to umpire in the major leagues. Hall of Fame umpire Bill McGowan was quoted in the 2005 book, Dean of Umpires: Bill McGowan, as saying that being teamed with Evans early in his career was “the greatest break of my life” and “whatever I’ve accomplished in my life, I owe to Billy Evans … and Tommy Connolly.”11

Yet Evans’s umpiring philosophy sounds like something straight out of a handbook: “Good eyes, plenty of courage – mental and physical – a thorough knowledge of the playing rules, more than average portions of fair play, common sense and diplomacy, an entire lack of vindictiveness, plenty of confidence in your ability.” Nonetheless, he was not afraid to admit his mistakes. He once called a ball foul before it stopped rolling. When the ball struck a pebble and bounced back into fair territory, the manager of the team at bat rushed onto the field, cursing Evans and demanding that he reverse his ruling. Billy responded, “Well, it would have been a fair ball yesterday and it will be fair tomorrow and for all years to come. But right now, unfortunately, it’s foul because that’s the way I called it.”12

During his 22-year umpiring career, Evans umpired 3,319 games and umpired six World Series. He umpired four no-hitters as well as Walter Johnson’s three consecutive shutouts of the New York Highlanders in 1908. A final point to Evans’ umpiring career came from Fielder Jones, who often had arguments with him: “We always liked to meet up with Evans on the road and knew he was to umpire.”13

Throughout his umpiring career, Evans continued to write about the game and the umpiring profession. He wrote frequent articles for the popular magazine Collier’s, as well as for The Sporting News. He authored two books, Knotty Problems of Baseball (1950) and in 1947 Umpiring From the Inside, a superb umpire’s manual that has withstood the test of time for its sound advice on the mechanics of umpiring and handling game situations. Among his tips for calling games were: You can’t be too thorough a student of the playing rules. Never take your eye off the ball. Never flaunt your authority. Always work on the theory that the fans came out to see the players perform. Never look for trouble. Treat players with the same consideration that you expect from them. Hustle every minute you are on the ballfield.14

Evans retired as an umpire in 1927 to become general manager of the Cleveland Indians. It was the first time the term “general manager” was used; before that almost every club had a business manager.15 During his nine years with Cleveland, the team showed steady improvement on the field and Evans was credited with signing Bob Feller, Tommy Henrich, Wes Ferrell, and Hal Trosky, among others. While attending Cleveland’s Amateur All-Star Game in 1929 with his wife, Hazel, he asked her if any young players impressed her, and she said, “That good looking Viking over there.”16 The player was Joe Vosmik, who spent a 13-year career with the Indians, St. Louis Browns, Boston Red Sox, Brooklyn, and Washington.

Evans left the Indians in 1935 because of a salary dispute and accepted a job as farm director for the Boston Red Sox. His tenure was marked by conflicts with owner Tom Yawkey and manager Joe Cronin. His association with Boston ended in October 1940 when he was fired by Yawkey. His trouble with Cronin came after Evans had persuaded Boston to purchase the Louisville Triple-A franchise. The player wanted by Evans was Pee Wee Reese. In July 1939 Cronin traded Reese to Brooklyn, thus beginning a major feud with Evans.17

In 1941 Evans became the general manager of the Cleveland Rams of the NFL, but left the next year and became president of the Southern Association. From 1942 until 1946, while many other minor leagues went bankrupt because of the manpower shortage during World War II, the Southern Association increased attendance from 700,000 to over 2 million. Evans also rewrote The Southern League Record Book which he said, “is what I consider my No. 1 achievement while president, but my biggest thrill came in getting the League thru 1943. All but ten leagues had folded, and when we finished in the black, I was really happy.”18

Evans got back to the major leagues in 1946 when he became executive vice president and general manager of the Detroit Tigers, a post he held until he retired in 1951. He sold slugger Hank Greenberg after the 1946 season for cash to the Pittsburgh Pirates, which was an unpopular move. Detroit never won a pennant during Evans’s tenure, and after the team collapsed in 1951 he left baseball forever.

Always a dapper dresser, Evans, a devout Presbyterian, was known as a good family man, though his baseball activities often kept him away from his Cleveland home. He married Hazel Baldwin in 1908 and the couple had one child, Robert, who enjoyed a successful career as a radio executive. Evans died at 71 in Miami, Florida, on January 23, 1956, after suffering a massive stroke while visiting his son. He was buried in Knollwood Cemetery in Mayfield Heights, Ohio. His greatest honor came posthumously in 1973 with election as the third umpire enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame (after Bill Klem and Tommy Connolly).

Last revised: March 22, 2021 (ghw)

This biography is included in “The SABR Book on Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Sources include Martin Appel and Burt Goldblatt, Baseball’s Best: The Hall of Fame Gallery (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977); Rich Marazzi’s entry on Evans in Mike Shatzkin, ed., The Ballplayers (New York: Arbor House, 1990); Jonathan Fraser Light, The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, 2005); James M. Kahn, The Umpire Story (New York: Putnam, 1953); and Dan E. Krueckeberg, “William George ‘Billy’ Evans,” in David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1987), 169.

2 “Billy Evans, Renowned Baseball Figure, Dies,” Youngstown Vindicator, January 24, 1956.

3 “Billy Evans, Scribe, Umpire and Executive, Dies at 71,” The Sporting News, February 1, 1956.

4 Billy Evans file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

5 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Third Edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 2007).

6 “Here He Is – the Perfect Umpire – Billy Evans,” Chicago Sunday Record-Herald, March 2, 1913; Grantland Rice, “About Umpires.” This is undated but refers to Evans and others; Billy Evans file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

7 The Old Scout, “Evans Umpired With Eyes Shut,” Billy Evans file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

8 “American League,” Sporting Life, June 1, 1907.

9 Ed Bang, “Courage as Young Strike-Caller Brought Evans Big Time Chance,” The Sporting News, February 1, 1956.

10 Billy Evans file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

11 Bob Luke, Dean of Umpires: Bill McGowan (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005).

12 Billy Evans file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

13 Billy Evans file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

14 Dave Anderson, “Seven timeless tips from a Hall of Famer,” Referee, August 1999.

15 Lee Allen, “Cooperstown Corner,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1967.

16 Jeff Carroll, Sam Rice: A Biography of the Washington Senators Hall of Famer (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007).

17 Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson, Red Sox Century: The Definitive History of Baseball’s Most Storied Franchise (Boston and New York: Houghton-Mifflin Company, 2000), 214, 216, 221, and 225.

18 Jack Fleischer, “Evans Provided Southern With Major League Class,” Memphis Press Scimitar, publication date not noted; in Billy Evans file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

William George Evans

Born

February 10, 1884 at Chicago, IL (US)

Died

January 23, 1956 at Miami, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.