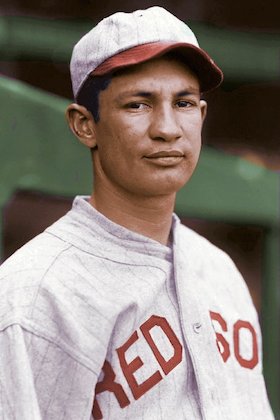

Buddy Myer

Buddy Myer was the “cocky little second baseman” of the Washington Senators when they won their last American League pennant in 1933. In 17 seasons in the majors, he won a batting title and was a two-time All-Star. Myer was often cited as one of the few Jewish baseball stars and was chosen for the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame, but he was a member of the Baptist church.1

Buddy Myer was the “cocky little second baseman” of the Washington Senators when they won their last American League pennant in 1933. In 17 seasons in the majors, he won a batting title and was a two-time All-Star. Myer was often cited as one of the few Jewish baseball stars and was chosen for the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame, but he was a member of the Baptist church.1

“Off the field he was the nicest, most placid guy in the world,” teammate George Case said, “but the moment he put on his baseball uniform his personality changed; he became aggressive and pugnacious. It was the most amazing thing. You wouldn’t think it was the same person.”2

Charles Solomon Myer Jr. was born in Ellisville, Mississippi, on March 16, 1904, the fourth of five children of Charles Solomon Myer and the former Maud Stevens. Charles Sr. and his brother J.P. owned a clothing store in Ellisville. The Myers were originally German Jews but had converted to Christianity in an earlier generation. Buddy Myer thought sportswriters assumed he was Jewish because of his name. “He was raised Baptist,” his son Dick said. “He didn’t think it was right when they inducted him into the Jewish Hall of Fame, but he didn’t correct them because he was afraid it would be taken the wrong way.”3

Buddy Myer attended Mississippi A&M, now Mississippi State, and played basketball (where he caught an elbow that left him with a flattened nose) and baseball, as the Aggies shortstop and leadoff hitter. He was a careless student—his future wife, Minnie Lee Williams, did much of his homework—and rebelled against the college’s military training requirements. He left school in 1925 to try out with the Cleveland Indians in spring training. The Indians were ready to sign him until he demanded a $1,000 bonus. The club told him to get lost. Cincinnati second baseman Hughie Critz, who had also attended A&M, recommended him to the Reds, but they passed.

Myer’s next stop was the New Orleans Pelicans’ training camp. When the Pelicans offered him a contract, his older brother, Jesse, stepped in to represent him and asked for the same $1,000 bonus. New Orleans manager Larry Gilbert said he had never heard of a young player demanding a bonus (probably not true) and had never seen a young player bring along an agent (probably true). The team gave him what he wanted.4

The Pelicans had an instant star, a left-handed hitting shortstop with quick feet and a quick bat. A first-year professional in the fast Class A Southern Association got the attention of major league scouts. Washington scout Joe Engel claimed to have stolen Myer from under the nose of a rival from the Chicago Cubs. Washington paid $17,500 for him in June, according to contemporary accounts, and agreed to let him stay with New Orleans for the rest of the season. Soon other big league clubs were offering more money. The Pelicans tried to buy him back from the Senators, but owner Clark Griffith wasn’t selling.

In August Myer was batting .336 when a spike wound on his leg became infected. He contracted blood poisoning, had surgery, and went home to recover. Griffith, hearing that his expensive prospect was seriously ill, sent his own man to fetch Myer to Washington. The young player was carried off the train on a stretcher.

His sudden departure raised a stink in New Orleans. Some fans suspected that Myer and Griffith had concocted a fake illness so the shortstop could join the Senators right away. Griffith denied the charge in a letter to a Times-Picayune columnist, adding that Myer “was deeply grieved to think anyone in New Orleans would accuse him of disloyalty, as he gave everything he had when he was playing for them.”5 After several weeks of treatment, he got into four games at the end of the season.

The Senators won their second straight American League pennant in 1925. In Game 2 of the World Series against Pittsburgh, Washington third baseman Ossie Bluege was beaned. Myer, seven months removed from a college campus, went in as a pinch runner and was thrown out stealing. He delivered a single in his only at-bat. He started the next two games at third before Bluege was able to return.

The Senators’ shortstop, Roger Peckinpaugh, had been named the American League Most Valuable Player in 1925, but he was the goat of the World Series, committing a record eight errors. The next spring Peckinpaugh, 35 years old and slowed by sore legs, lost his job to the 22-year-old Myer. By July the rookie was batting cleanup. He turned in what would be a typical Buddy Myer season at the plate: .304/.370/.380. But manager Bucky Harris, who was also the second baseman, complained about Myer’s defense. His 40 errors were third most among AL shortstops, even though he played only 118 games at short. Harris faulted his feeds on double-play balls, a critical skill for the manager who was on the receiving end.

The respected veteran Tris Speaker, who joined the Senators in 1927, told Harris and Griffith the club needed a new shortstop if it was going to contend. After Myer committed five errors in his first 15 games, Washington shuffled him off to the sorriest team in the league, the Boston Red Sox, in return for the shortstop Speaker recommended, Topper Rigney. Harris said, “Myer is not ready for the majors.”6

Myer’s .288/.359/.394 production with Boston was just about league average, but his defense at short failed to satisfy even a last-place club. In 1928 the Red Sox shifted him to third base. He led the team with a .313 batting average and led the league with 30 stolen bases.

In Washington, Rigney had been a bust; Clark Griffith wanted Myer back. After several weeks of dickering, he sent the Red Sox five players for his onetime reject. Counting what he had paid to acquire Myer from New Orleans, plus the value of the men he traded to Boston, Griffith estimated that Myer had cost him $150,000. “I must have been crazy to have let Myer go in the first place,” he said.7

Bucky Harris was gone from Washington, so the new manager, the former pitching great Walter Johnson, had to sort out a crowded infield. He had a slick-fielding third baseman in Ossie Bluege and Jackie Hayes was the favorite to replace Harris at second. Joe Cronin had won the shortstop job in 1928 but didn’t hit. Johnson and Griffith decided Bluege would move to short with Myer at third and Hayes at second. During spring training in 1929 the Senators and New York Giants barnstormed north together, and Giants manager John McGraw, a former third baseman, tutored Myer.

Johnson moved the pieces around the board before settling on Bluege at third, Cronin at short, and Myer at second—another new position. When Bluege went down with a knee injury, Myer stayed put and Hayes filled in at third. Through all the juggling, Myer’s bat was consistent: .300/.373/.403. In the heavy-hitting climate of 1929, that was no better than average, and the Senators brass still didn’t trust his defense. After four years as a regular player, he had to win his job again in 1930. Hayes was a better glove man but couldn’t match Myer’s bat or speed.

The Senators installed Myer as their leadoff hitter in 1931 and he was a fixture in the lineup after that. Griffith called him the most improved fielder in the league. But he quickly turned belligerent whenever a base runner hit him hard on a double play, maybe because he remembered the spiking that had sent him to a hospital in New Orleans. The writer Robert C. Ruark recalled him as a “cocky little second baseman [who] would hit you before he was properly introduced.”8

Early in the 1933 season, the Yankees’ Ben Chapman took him out with a hard slide, slicing open his shoe and cutting his foot. Myer kicked Chapman and Chapman fought back. Both men were ejected, but as Chapman passed through the Senators dugout on his way to the visitors’ clubhouse, he slugged Washington pitcher Earl Whitehill, igniting a near-riot that was remembered for years. The Senators swarmed Chapman, the Yankees charged across the field to his rescue, and angry fans joined the festivities. Police broke it up and arrested five civilians. Chapman, Myer, and Whitehill were suspended for five days and fined $100 each. (Chapman was traded to the Senators three years later. When he joined the team on the road, he walked into the hotel dining room and sat down beside Myer. They were soon talking and laughing together.)

With 26-year-old shortstop Joe Cronin taking over as manager, the Senators fought the Yankees for the 1933 pennant until August, when Washington won 13 straight games and pulled away. The Senators’ lineup included six regulars hitting over .290, backed by a pair of 20-game-winning pitchers. Myer’s .810 OPS was the best of his career so far. “I wasn’t the best player in the league that year, but I was the tiredest,” he remembered. “I led off in front of three good hitters—Goose Goslin, Heinie Manush and Cronin—and they put on the hit and run so many times, they had my tongue hanging out.”9

The club won a franchise-record 99 games on the way to its third pennant in 10 years and a meeting with the New York Giants in the World Series. Before Game 1, Myer was riding in a cab to the Polo Grounds when he witnessed a gory traffic accident in which a pedestrian was run down by a truck and killed. A superstitious man would call it an omen. Myer led off the game by striking out, the first of 10 victims of the NL’s Most Valuable Player, Carl Hubbell. He fumbled the first ground ball he saw in the bottom of the inning, leading to two unearned runs. He was charged with another error on a wild throw and a third when he dropped the catcher’s peg as Mel Ott tried to steal second. New York won, 4-2, and beat the Senators again the next day.

When the Series moved to Washington for Game 3, Myer led off the bottom of the first with a single and scored the Senators’ first run. He added an RBI double in the next inning and drove in another run with a seventh-inning single as Whitehill shut out the Giants, 4-0. It was the Senators’ only victory. New York won the championship in five games.

Injuries to three key players dragged Washington down to seventh place in 1934, beginning a long decline that continued until the franchise moved to Minnesota 27 years later. After the season, Griffith sold Cronin to the Boston Red Sox for $250,000. Cronin had married Griffith’s niece; the Washington owner thought Cronin could escape suspicions of nepotism and make more money in Boston.

Bucky Harris returned for his second term as the Senators’ manager in 1935 and named Myer the team captain. Myer was having his usual .300 season when Harris moved him from leadoff to the third spot in the order in June. Around the same time, his friend Bill Werber of the Red Sox gave him a lighter bat. He took off on a 21-game hitting streak that boosted his average to .347, one point ahead of Cleveland left fielder Joe Vosmik for the league lead.

In the 1930s, and for decades afterward, a player’s batting average was his meal ticket. A batting championship was the pinnacle of achievement. Myer, Vosmik, and Philadelphia’s Jimmie Foxx vied for the lead down the stretch. Going into the final day, Vosmik stood at .349, Myer at .345, and Foxx at .343.

Vosmik’s name was missing from the lineup for the first game of Cleveland’s season-ending doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns. It’s not clear whether he decided to sit out to protect his lead or his manager, Steve O’Neill, made the decision. Myer calculated that he needed four hits in the last game against the Athletics to win the title. He got three in his first four at-bats: a bunt single, a single to center, and another to left. In his final plate appearance, in the eighth inning, the count ran to 3-and-2. Myer thought a walk would kill his chances. He reached for a wide pitch and fouled it off, then cracked a long double to left-center. The 4-for-5 day (and 10 for his last 15) lifted his average to .349.

The news reached Cleveland late in the Indians’ first game. Vosmik hurried to the plate to pinch hit in the ninth but made an out. In the second game, he managed one single in three tries before darkness ended his season after six innings. The final averages: Myer .349026, Vosmik .348387, Foxx .345794.

By one account, Myer beat out 60 bunt hits during the season, a total impossible to verify. He was renowned as the game’s best drag bunter, who took advantage of the league’s slower first basemen. Opponents said the Washington groundskeepers sloped the foul lines inward so his bunts would stay fair, but Myer protested, “I got a lot of bunt base hits on the road, too.”10 He finished with 215 hits, one fewer than Vosmik, and walked 96 times for a .440 on-base percentage. He batted in 100 runs for the only time in his career. He also set a major league record (since broken) by turning 138 double plays, quite a feat for a man whose weak defense had once threatened his job. Vosmik, who led the league in hits, doubles, and triples, finished third and Myer fourth in the MVP voting.

Myer credited his big year—a batting average 36 points above his previous high—to giving up cigars and taking up golf. He said playing golf helped him stay in shape in the offseason and stopping smoking increased his energy, as well as pleasing Clark Griffith, an antismoking crusader. (Myer continued to chew unlit cigars.) He believed the switch from leadoff to third in the order was an advantage, because he didn’t feel the need to take as many pitches.

The batting championship earned Myer a $500 bonus from the league and a $4,500 raise from Griffith, to $14,000. As to what he was really worth, Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert offered a reported $200,000 for him. Griffith said, “Well, I sold Joe Cronin to Tom Yawkey for $250,000; Ruppert is worth twice as much as Yawkey, so I’m asking $500,000 for Myer.”11 New York writer Dan Daniel reported that the Yankees thought “the big army of Jewish fans of this tremendous Metropolitan area would be lured into the park by a Jewish star.”12 While the big dollars made good publicity, Myer stayed in Washington.

Comments on players’ ethnic backgrounds were common in a time when many American cities were full of first- and second-generation European immigrants. A player’s Irish, Italian, German, or even Bohemian (Joe Vosmik) ancestry was part of his public biography. Newspaper stories during Myer’s career routinely referred to him as a Jew. The sportswriter Fred Lieb ranked him as the second-greatest Jewish player of all time, after Hank Greenberg. (This was before Koufax.)13 Jewish writers such as Daniel and the Washington Post’s Shirley Povich, who covered the Senators every day, apparently never questioned his Jewishness. And Myer never denied it.

Myer had little opportunity to enjoy his batting title. In the spring of 1936 he began suffering from persistent stomach trouble. Some thought he was worried sick by his wife’s pregnancy, but other accounts say he had an ulcer. He played only 51 games before he went home in August.

He bounced back the next year to make the All-Star team for the second time. He never appeared in an All-Star Game; Detroit’s Charlie Gehringer was the AL’s premier second baseman and played every inning of the first six classics from 1933-1938.

Myer turned in another gaudy season at bat in 1938, with a line of .336/.454/.465, but he started only 117 games and was on the downslope at 34. When a wrist injury knocked him out of the lineup the next year, a 21-year-old rookie, Jimmy Bloodworth, staked his claim as the second baseman of the future.

In September 1940 Myer told Clark Griffith he was retiring to tend to his construction business in Mississippi. He had gotten a government contract to build army camps. Griffith persuaded him to play another year as a benchwarmer before he left the game for good.

Myer retired with a .303/.389/.406 batting line and 2,131 hits. Fifteen of his 38 lifetime home runs were inside the park, 13 of those hit into Griffith Stadium’s vast outfield. His speed and ability to draw walks made him a model leadoff man.

Myer settled his family in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he joined a mortgage bank. He enjoyed a prosperous life as a banker and real estate developer, golfer, and country club member. His elder child, Charles Stevens (Stevey) Myer, followed him into the real estate business. His younger son, William Richard (Dick), played on the professional golf tour in the 1960s. Buddy Myer had a heart attack in May 1974 and died on October 31 at age 70.

In a dissection of Hall of Fame voting, the analyst Bill James noted the uncanny similarity in the batting stats of Myer and a near-contemporary National League second baseman, Billy Herman.

| G | R | H | RBI | BA | OBP | SLG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myer | 1923 | 1174 | 2131 | 848 | .303 | .389 | .406 |

| Herman | 1922 | 1163 | 2345 | 839 | .304 | .367 | .407 |

Myer received a single vote from sportswriters in the Hall of Fame balloting; Herman attracted votes in several years, peaking at 20 percent (75 percent is required for election). He was elected by the veterans committee in 1975. James asked, “How in the world can you put one of those people in the Hall of Fame, and leave the other one out?”14

Selections by the Hall’s various veterans committees have been notoriously whimsical; those committees are responsible for most of the questionable inductions. James suggested that Herman benefited from the halo effect of his four World Series with the Cubs and Dodgers, and a long career as a manager and coach that kept him on the baseball radar. Myer spent the second half of his career with an irrelevant second-division team, then vanished from the game.

While James concluded that Herman and Myer were “of essentially the same value,”15 the two players’ reputations were quite different when they were active. They look virtually identical in lines of statistics, but not to those who saw them play. Herman started six All-Star Games in nine years and was the National League’s top second baseman between Frankie Frisch and Jackie Robinson. For much of Myer’s career, he was the American League’s third best behind Hall of Famers Gehringer and Tony Lazzeri.

It is an accident of timing that the AL had three outstanding second basemen when the NL had Herman and nobody else in particular. That accident colors their places in memory. Billy Herman was the National League’s best second baseman. Buddy Myer? Oh, yeah, him. Pretty good ballplayer.

It may be unfair, but that’s how history has passed it down.ss

Notes

1 Baton Rouge (Louisiana) Morning Advocate, November 1, 1974, 8. Myer’s obituary lists him as a member of the First Baptist Church of Baton Rouge.

2 Donald Honig, Baseball Between the Lines (repr. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 69.

3 Jackson (Mississippi) Clarion-Ledger, undated clipping (1987 or later) in Myer’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York. Gary Sarnoff and Bill Lamb provided additional research on Myer’s family.

4 Baton Rouge Advocate, August 1, 1962, 20.

5 New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 9, 1925, 14.

6 Washington Post, May 3, 1927, 15.

7 The Sporting News, November 16, 1974, 42.

8 Baton Rouge State Times Advocate, May 18, 1953, 6

9 The Sporting News, November 23, 1974, 52.

10 Baton Rouge State Times Advocate, May 31, 1981, C-6.

11 Washington Post, December 12, 1935, 17.

12 The Sporting News, October 24, 1935, 1.

13 Ibid., September 2, 1935, 3.

14 Bill James, The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Villard, 1986), 346.

15 Bill James, The Politics of Glory (New York: Macmillan, 1994), 109. The paperback edition of the book is titled What Ever Happened to the Hall of Fame?

Full Name

Charles Solomon Myer

Born

March 16, 1904 at Ellisville, MS (USA)

Died

October 31, 1974 at Baton Rouge, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.